Ego death

| Part of a series on |

| Spirituality |

|---|

|

Spiritual experience |

|

Spiritual development |

| Influences |

|

Western

|

| Research |

|

Ego death is a "complete loss of subjective self-identity."[1] The term is used in various intertwined contexts, with related meanings.

In Jungian psychology the synonymous term psychic death is used, which refers to a fundamental transformation of the psyche.[2]

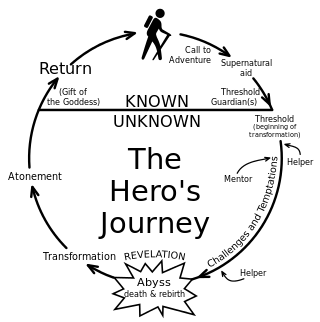

In the death and rebirth mythology, ego death is a phase of self-surrender and transition,[3][4][5][6] as described by Joseph Campbell in his research on the mythology of the Hero's Journey.[3] It is a recurrent theme in world mythology and is also used as a metaphor in some strands of contemporary western thinking.[6]

In (descriptions of) psychedelic experiences, the term is used synonymously with ego-loss,[7][8][1][9] to refer to (temporary) loss of one's sense of self due to the use of psychedelics.[10][11][1] The term was used as such by Timothy Leary et al.[1] to describe the (symbolic) death of the ego [12] in the first phase of a LSD-trip, in which a "complete transcendence" of the self[note 1] and the "game"[note 2] occurs.[13]

The concept is also used in contemporary spirituality and in the modern understanding of eastern religions to describe a permanent loss of "attachment to a separate sense of self"[web 1] and self-centeredness.[14]

Definitions

Various definitions can be found of ego death.

Mysticism

Daniel Merkur:

... an imageless experience in which there is no sense of personal identity. It is the experience that remains possible in a state of extremely deep trance when the ego-functions of reality-testing, sense-perception, memory, reason, fantasy and self-representation are repressed [...] Muslim Sufis call it fana (annihilation),[note 3] and medieval Jewish kabbalists termed it "the kiss of death."[15]

Jungian psychology

Ventegodt and Merrick:

... a fundamental transformation of the psyche. Such a shift in personality has been labeled an “ego death” in Buddhism or a psychic death by Jung.[16]

Comparative mythology

"Ego death" is the second phase of Joseph Campbell's description of The Hero's Journey,[4][5][6][3] which includes a phase of separation, transition, and incorporation.[6] The second phase is a phase of self-surrender and ego-death, where-after the hero returns to enrich the world with his discoveries.[4][5][6][3]

Psychedelics

According to Leary, Metzer & Alpert (1964), ego death, or ego loss as they call it, is part of the (symbolic) experience of death in which the old ego must die before one can be spiritually reborn.[13] Ego loss is

... complete transcendence − beyond words, beyond space−time, beyond self. There are no visions, no sense of self, no thoughts. There are only pure awareness and ecstatic freedom from all game (and biological) involvements. ["Games" are behavioral sequences defined by roles, rules, rituals, goals, strategies, values, language, characteristic space−time locations and characteristic patterns of movement. Any behavior not having these nine features is non− game: this includes physiological reflexes, spontaneous play, and transcendent awareness.][13]

Alnaes (1964):

[L]oss of ego-feeling.[10]

Stanislav Grof (1988)

[Ego-death is] a sense of total annihilation [...] This experience of ego death seems to entail an instant merciless destruction of all previous reference points in the life of the individual [...] [E]go death means an irreversible end to one's philosophical identification with what Alan Watts called skin-encapsulated ego.[17]

Daniel Merkur (1998) uses the term to refer to the "death crisis" which may occur during a trip:[18]

[The] death-rebirth experience [is] also described in the literature as "ego death." It is sometimes termed "ego loss" [...] The death crisis takes various forms. The early examples in a series of death crises are usually attended by extreme panic.[18]

Michael Hoffman (2006-2007):

Ego death is the cessation, in the intense mystic altered state, of the sense and feeling of being a control-wielding agent moving through time and space. The sensation of wielding control is replaced by the experience of being helplessly, powerlessly embedded in spacetime as purely a product of spacetime, with control-thoughts being perceptibly inserted or set into the stream of thought by a hidden, uncontrollable source.[web 2]

Johnson, Richards & Griffiths (2008), paraphrasing Leary et al. and Grof:

The individual may temporarily experience a complete loss of subjective self-identity, a phenomenon sometimes referred to as ‘ego loss’ or ‘ego death’.[1]

John Harrison (2010):

[T]emporary ego death [is the] loss of the separate self[,] or, in the affirmative, [...] a deep and profound merging with the transcendent other.[11]

Spirituality

Carter Phipps:

Enlightenment equals ego death [...] the renunciation, rejection and, ultimately, the death of the need to hold on to a separate, self-centered existence.[19][note 4]

Development of the concept

The concept of "ego death" developed along a number of intertwined strands of thought, especially romantic movements[21] and subcultures,[22] Theosophy,[23] anthropological research on rites de passage[24] and shamanism[22] Joseph Campbell's comparative mythology,[4][5][6][3] Jungian psychology,[25][3] the psychedelic scene of the 1960s,[26] and transpersonal psychology.[27]

Western mysticism

According to Merkur,

The conceptualisation of mystical union as the soul's death, and its replacement by God's consciousness, has been a standard Roman Catholic trope since St. Teresa of Ávila; the motif traces back through Marguerite Porete, in the 13th century, to the fana,[note 3] "annihilation", of the Islamic Sufis.[28]

Jungian psychology

According to Ventegodt and Merrick, the Jungian term "psychic death" is a synonym for "ego death":

In order to radically improve global quality of life, it seems necessary to have a fundamental transformation of the psyche. Such a shift in personality has been labeled an "ego death" in Buddhism or a psychic death by Jung, because it implies a shift back to the existential position of the natural self, i.e., living the true purpose of life. The problem of healing and improving the global quality of life seems strongly connected to the unpleasantness of the ego-death experience.[16]

Ventegodt and Merrick refer to Jung's publications The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious, first published 1933, and Psychology and Alchemy, first published in 1944.[16][note 5]

In Jungian psychology, a unification of archetypal opposites has to be reached, during a process of conscious suffering, in which consciousness "dies" and resurrects. Jung called this process "the transcendent function",[note 6] which leads to a "more inclusive and synthetic consciousness."[29]

Jung used analogies with alchemy to describe the individuation process, and the transference-processes which occur during therapy.[30]

According to Leeming et al., from a religious point of view psychic death is related to St. John of the Cross' Ascent of Mt. Carmel and Dark Night of the Soul.[31]

Mythology - The Hero with a Thousand Faces

In 1949 Joseph Campbell published The Hero with a Thousand Faces, a study on the archetype of the Hero's Journey.[3] It describes a common theme found in many cultures worldwide,[3] and is also described in many contemporary theories on personal transformation.[6] In traditional cultures it describes the "wilderness passage",[3] the transition from adolescence into adulthood.[24] It typically includes a phase of separation, transition, and incorporation.[6] The second phase is a phase of self-surrender and ego-death, whereafter the hero returns to enrich the world with his discoveries.[4][5][6][3] Campbell describes the basic theme as follows:

A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.[32]

This journey is based on the archetype of death and rebirth,[5] in which the "false self" is surrendered and the "true self" emerges.[5] A well known example is Dante's Divina Comedia, in which the hero descends into the underworld.[5]

Psychedelics

Bohemianism

Bohemianism was a distinctive component of the 19th century romanticism, which reached New York in the 1830s.[21] Drug-use, particularly hashish and opium, was an integral part of this 19th century romanticism.[21] Occult or esoteric components were added between 1900 and 1920.[21] By the 1920s, American Bohemianism involved a "system of ideas":[21]

[S]alvation by the child (within), self-expression, paganism, living for the moment, liberty, female equality, psychological adjustment, and changing location.[21]

These values were inherited by both the Beat Generation and the hippies.[21]

1950s Beat Generation and Aldous Huxley

In the 1940s an interest in Native American peyotism had developed among anthropology-students in San Francisco.[22] Beat poets in San Francisco, such as Allen Ginsberg, Gary Snyder and Michael McClure integrated peyotism into their bohemianism, around the time that Aldous Huxley published The Doors of Perception.[22]

Aldous Huxley already in the 1950s propagated the use of psychedelics, starting with The Doors of Perception, published in 1954.[33] Huxley also promoted a set of analogies with eastern religions, which inspired the 1960s belief in a revolution in western consciousness.[33] The Tibetan Book of the Dead was one of his sources.[33]

Alan Watts had a profound influence on the psychedelic experiences of the beats and the early hippies.[34] His opening statement on mystical experiences in This Is It draws parallels with Richard Bucke's Cosmic Consciousness, describing the "central core" of the experience as

... the conviction, or insight, that the immediate now, whatever its nature, is the goal and fulfillment of all living.[34]

1960 hippies

The use of drugs was an important part of the emerging 1960s hippie-scene of San Francisco.[35] In 1964 William S. Burroughs drew a distinction between "sedative" and "conscious-expanding" drugs.[36] The distinction was taken over by the hippies, calling sedatives "drugs", and conscious-expanding substances "dope".[37]

LSD-research

In the 1940s and 1950s the use of LSD was restricted to military and psychiatric researchers. By the end of the 1950s, a number of researchers began to share LSD with their friends in private situations.[37] LSD was criminalized in 1966.[38]

Timothy Leary

One of those researchers was Timothy Leary, a clinical psychologist who first encountered psychedelic drugs while on vacation in 1960,[39] and started to research the effects of psilocybin in 1961.[33] He sought advice from Aldous Huxley, who advised him to propagate psychedelic drugs among society's elites, including artists and intellectuals.[39] On insistence of Allen Ginsberg, Leary, together with his younger colleague Richard Alpert (Ram Dass) also made LSD available to students.[39] In 1962 Leary was fired, and Harvard's psychedelic research program was shut down.[39] In 1962 Leary founded the Castalia Foundation,[39] and in 1963 he and his colleagues founded the journal The Psychedelic Review.[40]

Randolf Alnaes

In 1964 Randolf Alnaes published "Therapeutic applications of the change in consciousness produced by psycholytica (LSD, Psilocyrin, etc.)."[41][10] Alnaes notes that patients may become involved in existential problems as a consequence of the LSD experience. Psycholytic drugs may facilitate insight. With a short psychological treatment, patients may benefit from changes brought about by the effects of the experience.[41]

One of the LSD-experiences may be the death crisis. Alnaes discernes three stages in this kind of experience:[10]

- Psychosomatic symptoms lead up to the "loss of ego feeling (ego death)";[10]

- A sense of separation of the observing subject from the body. The body is beheld to undergo death or an associated event;

- "Rebirth", the return to normal, conscious mentation, "characteristically involving a tremendous sense of relief, which is cathartic in nature and may lead to insight."[10]

The Psychedelic Experience

Manual for LSD-usage

Following Huxley's advice, Leary also wrote a manual for LSD-usage.[40] The Psychedelic Experience, published in 1964, is a guide for LSD-trips, written by Timothy Leary, Ralph Metzner and Richard Alpert, loosely based on Yvan-Wentz's translation of the Tibetan Book of the Dead.[40][33] Aldous Huxley introduced the Tibetan Book of the Dead to Timothy Leary.[33] According to Leary, Metzer and Alpert, the Tibetan Book of the Dead is

... a key to the innermost recesses of the human mind, and a guide for initiates, and for those who are seeking the spiritual path of liberation.[42]

They construed the effect of LSD as a "stripping away" of ego-defenses, finding parallels between the stages of death and rebirth in the Tibetan Book of the Dead, and the stages of psychological "death" and "rebirth" which Leary had identified during his research.[43] According to Leary, Metzer and Alpert it is....

... one of the oldest and most universal practices for the initiate to go through the experience of death before he can be spiritually reborn. Symbolically he must die to his past, and to his old ego, before he can take his place in the new spiritual life into which he has been initiated.[12]

The Bardos

In The Psychedelic Experience, three stages are discerned:

- Chikhai Bardo: ego loss, a "complete transcendence" of the self[note 1] and game;[13][note 2]

- Chonyid Bardo: The Period of Hallucinations;[44]

- Sidpa Bardo: the return to routine game reality and the self.[13]

Each Bardo is described in the first part of The Psychedelic Experience. In the second part, instructions are given which can be read to the "voyager". The instructions for the First Bardo state:

O (name of voyager)

The time has come for you to seek new levels of reality.

Your ego and the (name) game are about to cease.

You are about to be set face to face with the Clear Light

You are about to experience it in its reality.

In the ego−free state, wherein all things are like the void and cloudless sky,

And the naked spotless intellect is like a transparent vacuum;

At this moment, know yourself and abide in that state.

O (name of voyager),

That which is called ego−death is coming to you.

Remember:

This is now the hour of death and rebirth;

Take advantage of this temporary death to obtain the perfect state −

Enlightenment.[45]

Stanislav Grof

Stanislav Grof has researched the effects of psychedelic substances,[46] which can also be induced by nonpharmological means.[47] Grof has developed a "cartography of the psyche" based on his clinical work with psychedelics,[48] which describe the "basic types of experience that become available to an average person" when using psychedelics or "various powerful non-pharmacological experiential techniques".[49]

According to Grof, traditional psychiatry, psychology and psychotherapy use a model of the human personality that is limited to biography and the individual consciousness, as described by Freud.[50] This model is inadequate to describe the experiences which result from the use of psychedelics and the use of "powerful techniques", which activate and mobilize "deep unconscious and superconscious levels of the human psyche".[50] These levels include:[27]

- The Sensory Barrier and the Recollective-Biographical Barrier

- The Perinatal Matrices:

- BPM I: The Amniotic Universe. Maternal womb; symbiotic unity of the fetus with the maternal organism; lack of boundaries and obstructions;

- BPM II: Cosmic Engulfment and No Exit. Onset of labor; alteration of blissful connection with the mother and its pristine universe;

- BPM III: The Death-Rebirth Struggle. Movement through the birth channel and struggle for survival;

- BPM IV: The Death-Rebirth Experience. Birth and release.

- The Transpersonal Dimensions of the Psyche

Ego death appears in the fourth Perinatal Matrix.[27] This matrix is related to the stage of delivery, the actual birth of the child.[51] The build up of tension, pain and anxiety is suddenly released.[51] The symbolic counterpart is the Death-Rebirth Experience, in which the individual may have a strong feeling of impending catastrophe, and may be desperately struggling to stop this process.[17] The transition from BPM III to BPM IV may involve a sense of total annihilation:[17]

This experience of ego death seems to entail an instant merciless destruction of all previous reference points in the life of the individual.[17]

According to Grof what dies in this process is "a basically paranoid attitude toward the world which reflects the negative experience of the subject during childbirth and later."[17] When experienced in its final and most complete form,

...ego death means an irreversible end to one's philosophical identification with what Alan Watts called skin-encapsulated ego."[17]

Recent research

Recent research also mentions that ego loss is sometimes experienced by those under the influence of psychedelic drugs.[52]

The Ego-Dissolution Inventory is a validated self-report questionnaire that allows for the measurement of transient ego-dissolution experiences occasioned by psychedelic drugs. [53]

Spirituality

Following the interest in psychedelics and spirituality, the term "ego death" has been used to describe the eastern notion of "enlightenment" (bodhi) or moksha.

Buddhism

Zen practice is said to lead to ego-death.[54] Ego-death is also called "great death", in contrast to the physical "small death."[55] According to Jin Y. Park, the ego death that Buddhism encourages makes an end to the "usually-unconsciousness-and-automated quest" to understand the sense-of-self as a thing, instead of as a process.[56] According to Park, meditation is learning how to die by learning to "forget" the sense of self:[56]

Enlightenment occurs when the usually automatized reflexivity of consciousness ceases, which is experienced as a letting-go and falling into the void and being wiped out of existence [...] [W]hen consciousness stops trying to catch its own tail, I become nothing, and discover that I am everything.[57]

According to Welwood, "egolessness" is a common experience. Egolessness appears "in the gaps and spaces between thoughts, which usually go unnoticed".[58] Existential anxiety arises when one realizes that the feeling of "I" is nothing more than a perception. According to Welwood, only egoless awareness allows us to face and accept death in all forms.[58]

David Loy also mentions the fear of death,[59] and the need to undergo ego-death to realize our true nature.[60][61] According to Loy, our fear of egolessness may even be stronger than our fear of death.[59]

"Egolessness" is not the same as anatta, non-self. Anatta means not to take the constituents of the person as a permanent entity:

the Buddha, almost ad nauseam, spoke against wrong identification with the Five Aggregates, or the same, wrong identification with the psychophysical believing it is our self. These aggregates of form, feeling, thought, inclination, and sensory consciousness, he went on to say, were illusory; they belonged to Mara the Evil One; they were impermanent and painful. And for these reasons, the aggregates cannot be our self. [web 3]

Bernadette Roberts

Bernadette Roberts makes a distinction between "no ego" and "no self".[62][63] According to Roberts, the falling away of the ego is not the same as the falling away of the self.[64] "No ego" comes prior to the unitive state; with the falling away of the unitive state comes "no self".[65] "Ego" is defined by Roberts as

... the immature self or consciousness prior to the falling away of its self-center and the revelation of a divine center.[66]

Roberts defines "self" as

... the totality of consciousness, the entire human dimension of knowing, feeling and experiencing from the consciousness and unconsciousness to the unitive, transcendental or God-consciousness.[66]

Ultimately, all experiences on which these definitions are based are wiped out or dissolved.[66] Jeff Shore further explains that "no self" means "the permanent ceasing, the falling away once and for all, of the entire mechanism of reflective self-consciousness".[67]

According to Roberts, both the Buddha and Christ embody the falling away of self, and the state of "no self". The falling away is represented by the Buddha prior to his enlightenment, starving himself by ascetic practices, and by the dying Jesus on the cross; the state of "no self" is represented by the enlightened Buddha with his serenity, and by the resurrected Christ.[66]

Integration

Psychedelics

According to Nick Bromell, ego death is a tempering though frightening experience, which may lead to a reconciliation with the insight that there is no real self.[68]

According to Grof, death crises may occur over a series of psychedelic sessions until they cease to lead to panic. A conscious effort not to panic may lead to a "pseudohallicinatory sense of transcending physical death."[10] According to Merkur,

Repeated experience of the death crisis and its confrontation with the idea of physical death leads finally to an acceptance of personal mortality, without further illusions. The death crisis is then greeted with equanimity.[10]

Vedanta and Zen

Both the Vedanta and the Zen-Buddhist tradition warn that insight into the emptiness of the self, or so-called "enlightenment experiences", are not sufficient; further practice is necessary.

Jacobs warns that Advaita Vedanta practice takes years of committed practice to sever the "occlusion"[69] of the so-called "vasanas, samskaras, bodily sheaths and vrittis", and the "granthi[note 7] or knot forming identification between Self and mind".[70]

Zen Buddhist training does not end with kenshō, or insight into one's true nature. Practice is to be continued to deepen the insight and to express it in daily life.[71][72][73][74] According to Hakuin, the main aim of "post-satori practice"[75][76] (gogo no shugyo[77] or kojo, "going beyond"[78]) is to cultivate the "Mind of Enlightenment".[79] According to Yamada Koun, "if you cannot weep with a person who is crying, there is no kensho".[80]

Dark Night and depersonalisation

Shinzen Young, an American Buddhist teacher, has pointed at the difficulty integrating the experience of no self. He calls this "the Dark Night", or

... "falling into the Pit of the Void." It entails an authentic and irreversible insight into Emptiness and No Self. What makes it problematic is that the person interprets it as a bad trip. Instead of being empowering and fulfilling, the way Buddhist literature claims it will be, it turns into the opposite. In a sense, it's Enlightenment's Evil Twin.[web 4]

Willoughby Britton is conducting research on such phenomena which may occur during meditation, in a research program called "The Dark Knight of the Soul".[web 5] She's searched texts from various traditions to find descriptions of difficult periods on the spiritual path,[web 6] and conducted interviews to find out more on the difficult sides of meditation.[web 5][note 8]

Theoretical background

Leary's terminology

Leary developed the concept of "ego death" as a description of unitive states.[28] Merkur further notes that, accurately described, not the ego, but the self-representation disappears.[28] The ego, "defined as the seat of experience", continues to function.[28]

Perennial philosophy

1960s studies of mysticism were generally informed by the "common core thesis", the idea that mystical experiences are essentially the same,[81] independent of the sociocultural, historical and religious context in which it occurs.[82] This idea was also popular among the hippies.[81]

In the 19th century perennialism gained popularity as a model for perceiving similarities across a broad range of religious traditions.[83] William James, in his The Varieties of Religious Experience, was highly influential in further popularising this perennial approach and the notion of personal experience as a validation of religious truths.[84]

Aldous Huxley was a major proponent of the Perennial philosophy. He "was heavily influenced in his description by Vivekananda's neo-Vedanta and the idiosyncratic version of Zen exported to the west by D.T. Suzuki. Both of these thinkers expounded their versions of the perennialist thesis",[85] which they originally received from western thinkers and theologians.[83]

The perennial position is "largely dismissed by scholars",[86] but "has lost none of its popularity".[87]

Evans-Wentz translation

According to John Myrdhin Reynolds, Evans-Wentz's translation of the Tibetan Book of the Dead introduced a number of misunderstandings about Dzogchen.[88] Evans-Wentz was well acquainted with Theosophy, and used this framework to interpret the translation of The Tibetan Book of the Dead, which was largely provided by two Tibetan lamas who spoke English, Lama Sumdhon Paul and Lama Lobzang Mingnur Dorje.[23] Evans-Wentz was not familiar with Tibetan Buddhism,[88] and his view of Tibetan Buddhism was "fundamentally neither Tibetan nor Buddhist, but Theosophical and Vedantist."[89] He introduced a terminology into the translation which was largely derived from Hinduism, as well as from his Theosophical beliefs.[88]

Also Jung's introduction betrays a misunderstanding of Tibetan Buddhism, using the text to discuss his own theory of the unconsciousness.[90]

Research on mysticism

Ralph Hood incorporated the term in the Hood Mysticism scale.[91] Hood identified two factors, "intense experience" and "joyful experience".[92] Factor I contains three "ego loss" items, factor II contains one "ego loss" item.[93]

Influence

The propagation of LSD-induced "mystical experiences", and the concept of ego death, had some influence in the 1960s, but Leary's brand of LSD-spirituality never "quite caught on."[94]

Reports of psychedelic experiences

Leary's terminology influenced the understanding and description of the effects of psychedelics. Various reports by hippies of their psychedelic experiences describe states of diminished consciousness which were labelled as "ego death", but do not match Leary's descriptions.[95] Panic attacks were occasionally also labeled as "ego death".[96]

The Beatles

John Lennon read The Psychedelic Experience, and was strongly affected by it.[97] He wrote "Tomorrow Never Knows" after reading the book, as a guide for his LSD-trips.[97] Lennon took about a thousand acid-trips, but it only exacerbated his personal difficulties.[98] Eventually John Lennon stopped using the drug. George Harrison and Paul McCartney also concluded that LSD use didn't result in any worthwhile changes.[99]

Radical pluralism

According to Bromell, the experience of ego death confirms a radical pluralism that most people experience in their youth, but prefer to flee from, instead believing in a stable self and a fixed reality.[100] He further states this also led to a different attitude among youngsters in the 1960s, rejecting the lifestyle of their parents as being deceitful and false.[100]

Criticism of ego death as seen through LSD use

Fatal accidents involving LSD

Dan Merkur notes that the use of LSD in combination with Leary's manual often did not lead to liberating insights, but to horrifying bad trips.[101] It also lead to fatal accidents, which were trivialized by Alpert.[102]

Tim Leary as charlatan

Hunter S. Thompson, who tried LSD,[103] criticized Leary as a charlatan who was exploiting the credulity of large numbers of disaffected people.[103] Thompson perceived a self-centered base in Leary's work, placing himself at the centre of his texts, using his persona as "an exemplary ego, not a dissolved one."[103]

Brad Warner

Sōtō-Zen teacher Brad Warner has repeatedly criticized the idea that psychedelic experiences lead to "enlightenment experiences."[note 9] In response to The Psychedelic Experience he wrote:

While I was at Starwood, I was getting mightily annoyed by all the people out there who were deluding themselves and others into believing that a cheap dose of acid, 'shrooms, peyote, "molly" or whatever was going to get them to a higher spiritual plane [...] While I was at that campsite I sat and read most of the book The Psychedelic Experience by Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert (aka Baba Ram Dass, later of Be Here Now fame). It's a book about the authors' deeply mistaken reading of the Tibetan Book of the Dead as a guide for the drug taking experience [...] It was one thing to believe in 1964 that a brave new tripped out age was about to dawn. It's quite another to still believe that now, having seen what the last 47 years have shown us about where that path leads. If you want some examples, how about Jimi Hendrix, Sid Vicious, Syd Barrett, John Entwistle, Kurt Cobain... Do I really need to get so cliched with this? Come on now.[web 7]

It is noteworthy that Richard Alpert's position on psychedelic use has changed by as early as 1976.[104]

See also

- Ahamkara

- Altered states of consciousness

- Bad trip

- Carl Gustav Jung

- Carlos Castaneda

- Charles Sanders Peirce

- Cognitive dissonance

- Collective unconscious

- Compartmentalization

- Dance of death

- Death, Brain death, and Near-death experience

- Depersonalization and derealization

- Ego (religion)

- Fana (Sufism)

- Ego in Spiritual materialism

- Ethnomycology

- Existentialism

- Ganzfeld effect

- Gnosis and Kenosis

- Holotropic Breathwork

- Kensho

- Monism

- Mystical psychosis

- Mysticism

- Neo-shamanism

- Neo-Advaita

- Night of Pan

- Nondualism

- Parapsychology

- Psychedelia

- Psychedelic experience and Entheogenics

- Self (philosophy)

- Self (spirituality)

- Sotāpanna

- Theosophy

Notes

- 1 2 Leary et al.: "The first period (Chikhai Bardo) is that of complete transcendence − beyond words, beyond space−time, beyond self. There are no visions, no sense of self, no thoughts. There are only pure awareness and ecstatic freedom from all game (and biological) involvements."[13]

- 1 2 Leary et al.: ""Games" are behavioral sequences defined by roles, rules, rituals, goals, strategies, values, language, characteristic space−time locations and characteristic patterns of movement.[13]

- 1 2 See also Encyclopedia Britannica, Fana, and Christopher Vitale,

- ↑ Cited in Rindfleisch 2007[20] and White 2012,[14] and in "Nondual Highlights Issue #1694 Saturday, January 31, 2004": "[E]go death [is] the final destruction of our attachment to a separate sense of self."[web 1]

- ↑ The term is also being used by Poul Bjerre, in his 1929 publication Död och Förnyelse, "Death and Renewal".

- ↑ See Frith Luton, Transcendent Function, and Miller, Jeffrey C. (2012), The Transcendent Function Jung's Model of Psychological Growth through Dialogue with the Unconscious (PDF), SUNY

- ↑ See The Knot of the Heart

- ↑ See also Brad Warner (June 27, 2014), Zen Freak Outs!

- ↑ See:

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Johnson, Richards & Griffiths 2008.

- ↑ Ventegodt & Merrick 2003, p. 1021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Taylor 2008, p. 1749.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Plotkin 2010, p. 467, note 1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Rosen 1998, p. 228.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Atkinson 1995, p. 31.

- ↑ Leary, Metzner & Alpert 1964, p. 14.

- ↑ Merkur 1998, p. 58.

- ↑ Dickins 2014, p. 374.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Merkur 1998, p. 60.

- 1 2 Harrison 2010.

- 1 2 Leary, Metzner & Alpert 1964, p. 12.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Leary, Metzner & Alpert 1964, p. 5.

- 1 2 White 2012, p. 7.

- ↑ Merkur 2007, p. 66.

- 1 2 3 Ventegodt & Merrick 2003, p. 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Grof 1988, p. 30.

- 1 2 Merkur 1998, p. 58-59.

- ↑ Phipps 2001.

- ↑ Rindfleisch 2007, p. 66.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Merkur 2014, p. 211.

- 1 2 3 4 Merkur 2014, p. 212.

- 1 2 Reynolds 1989, p. 72-73, 78.

- 1 2 Taylor 2008, p. 1748-1749.

- ↑ Rosen 1998, p. 226.

- ↑ Merkur 2014, p. 219-221.

- 1 2 3 Grof 1988.

- 1 2 3 4 Merkur 2014, p. 225.

- ↑ Dourley 2008, p. 106.

- ↑ Fordham 1990.

- ↑ Leeming, Madden & Marlan 2009, p. 40.

- ↑ Campbell 1949, p. 23.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gould 2007, p. 218.

- 1 2 Merkur 2014, p. 213.

- ↑ Merkur 2014, p. 213-218.

- ↑ Merkur 2014, p. 218.

- 1 2 Merkur 2014, p. 219.

- ↑ Merkur 2014, p. 219-220.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Merkur 2014, p. 220.

- 1 2 3 Merkur 2014, p. 221.

- 1 2 Alnaes 1964.

- ↑ Leary, Metzner & Alpert 1964, p. 11.

- ↑ Gould 2007, p. 218-219.

- ↑ Leary, Metzner & Alpert 1964, p. 20.

- ↑ Leary, Metzner & Alpert 1964, p. 49.

- ↑ Grof 1988, p. xi.

- ↑ Grof 1988, p. xiii-xiv.

- ↑ Grof 1988, p. xvi.

- ↑ grof 1988, p. xvi.

- 1 2 Grof 1988, p. 1.

- 1 2 Grof 1988, p. 29.

- ↑ Lyvers & Meester 2012.

- ↑ Nour 2016.

- ↑ Safran 2012.

- ↑ Lama Surya Das 2010.

- 1 2 Park 2006, p. 78.

- ↑ Park 2006, p. 78-79.

- 1 2 Welwood 2014.

- 1 2 Loy 2000.

- ↑ Loy 2000, p. 22.

- ↑ Loy 2003, p. 4.

- ↑ Shore 2004.

- ↑ Roberts 2004.

- ↑ Roberts 2004, p. 49.

- ↑ Roberts 2004, p. 49-50.

- 1 2 3 4 Roberts 2004, p. 52.

- ↑ Shore 2004, p. xi.

- ↑ Bromell 2002, p. 79.

- ↑ Jacobs 2004, p. 84.

- ↑ Jacobs 2004, p. 85.

- ↑ Sekida 1996.

- ↑ Kapleau 1989.

- ↑ Kraft 1997, p. 91.

- ↑ Maezumi 2007, p. 54, 140.

- ↑ Waddell 2004, p. xxv-xxvii.

- ↑ Hisamatsu 2002, p. 22.

- ↑ Hori 2006, p. 145.

- ↑ Hori 2006, p. 144.

- ↑ Yoshizawa 2009, p. 41.

- ↑ MacInnes 2007, p. 75.

- 1 2 Merkur 2014, p. 207.

- ↑ Katz 2000, p. 3.

- 1 2 King 2002.

- ↑ Harmless 2007, pp. 10–17.

- ↑ King 2002, p. 163.

- ↑ McMahan 2008, p. 269, note 9.

- ↑ McMahan 2010, p. 269, note 9.

- 1 2 3 Reynolds 1989, p. 71.

- ↑ Reynolds 1989, p. 78.

- ↑ Reynolds 1989, p. 110.

- ↑ Hood 1975.

- ↑ Hood 1975, p. 34.

- ↑ Hood 1975, p. 33.

- ↑ Merkur 2014, p. 222.

- ↑ Merkur 2014, p. 225-227.

- ↑ Merkur 2014, p. 227.

- 1 2 Conners 2013.

- ↑ Lee & Shlain 1992, p. 182-183.

- ↑ Lee & Shlain 1992, p. 183-184.

- 1 2 Bromell 2002, p. 80.

- ↑ Merkur 2014, p. 222-223.

- ↑ Merkur 2014, p. 224.

- 1 2 3 Stephenson 2011.

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9GB6wMWi-O4

Sources

Printed sources

- Alnaes, Randolf (1964), "Therapeutic applications of the change in consciousness produced by psycholytica (LSD, Psilocyrin, etc.)", Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 39: 397–409, doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1964.tb04952.x

- Atkinson, Robert (1995), The Gift of Stories: Practical and Spiritual Applications of Autobiography, Life Stories, and Personal Mythmaking, Greenwood Publishing Group

- Bromell, Nick (2002), Tomorrow Never Knows: Rock and Psychedelics in the 1960s, University of Chicago Press

- Campbell, Joseph (1949), The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Princeton University Press

- Chapman, Rob (2010), A Very Irregular Head: The Life of Syd Barrett, Da Capo Press

- Conners, Peter (2013), White Hand Society: The Psychedelic Partnership of Timothy Leary & Allen Ginsberg, City Lights Books

- Dickins, Robert (2014), Variety of Religious Paths in Psychedelic Literature. In: J. Harold Ellens (ed.), "Seeking the Sacred with Psychoactive Substances: Chemical Paths to Spirituality and to God", ABC-CLIO

- Dourley, John P. (2008), Paul Tillich, Carl Jung and the Recovery of Religion, Routledge

- Ellens, J. Harold (2014), Seeking the Sacred with Psychoactive Substances: Chemical Paths to Spirituality and to God, ABC-CLIO

- Fordham, Michael (1990), Jungian Psychotherapy: A Study in Analytical Psychology, Karnac Books

- Gould, Jonathan (2007), Can't Buy Me Love: The Beatles, Britain, and America, Crown Publishing Group

- Grof, Stanislav (1988), The Adventure of Self-Discovery. Dimensions of Consciousness and New Perspectives in Psychotherapy and Inner Exploration, SUNY Press

- Harmless, William (2007), Mystics, Oxford University Press

- Harrison, John (2010), Ego Death & Psychedelics (PDF), MAPS

- Hisamatsu, Shinʼichi (2002), Critical Sermons of the Zen Tradition: Hisamatsu's Talks on Linji, University of Hawaii Press

- Hood, Ralph W. (1975), "The Construction and Preliminary Validation of a Measure of Reported Mystical Experience", Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 14 (1): 29, doi:10.2307/1384454

- Jacobs, Alan (2004), "Advaita and Western Neo-Advaita", The Mountain Path Journal, Ramanasramam: 81–88

- Johnson, M.W.; Richards, W.A.; Griffiths, R.R. (2008), "Human hallucinogen research: guidelines for safety" (PDF), Journal of Psychopharmacology, 22 (6): 603–620, doi:10.1177/0269881108093587, PMC 3056407

, PMID 18593734

, PMID 18593734 - Kapleau, Philip (1989), The three pillars of Zen

- Katz, Steven T. (2000), Mysticism and Sacred Scripture, Oxford University Press

- King, Richard (2002), Orientalism and Religion: Post-Colonial Theory, India and "The Mystic East", Routledge

- Kraft, Kenneth (1997), Eloquent Zen: Daitō and Early Japanese Zen, University of Hawaii Press

- Lama Surya Das (2010), Awakening To The Sacred, Random House

- Leary, Timothy; Metzner, Ralph; Alpert, Richard (1964), THE PSYCHEDELIC EXPERIENCE. A manual based on THE TIBETAN BOOK OF THE DEAD (PDF)

- Lee, Martin A.; Shlain, Bruce (1992), Acid Dreams: The Complete Social History of LSD : the CIA, the Sixties, and Beyond, Grove Press

- Leeming, David A.; Madden, Kathryn; Marlan, Stanton (2009), Encyclopedia of Psychology and Religion: L-Z, Springer Science & Business Media

- Loy, David (2000), Lack and transcendence: the problem of death and life in psychotherapy, existentialism, and Buddhism, Humanity Books

- Loy, David (2003), The Great Awakening: A Buddhist Social Theory, Wisdom Publications Inc.

- Lyvers, M.; Meester, M. (2012), "Illicit Use of LSD or Psilocybin, but not MDMA or Nonpsychedelic Drugs, is Associated with Mystical Experiences in a Dose-Dependent Manner.", Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 44 (5): 410–417, doi:10.1080/02791072.2012.736842

- MacInnes, Elaine (2007), The Flowing Bridge: Guidance on Beginning Zen Koans, Wisdom Publications

- Maezumi, Taizan; Glassman, Bernie (2007), The Hazy Moon of Enlightenment, Wisdom Publications

- McMahan, David L. (2008), The Making of Buddhist Modernism, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780195183276

- Merkur, Daniel (1998), The Ecstatic Imagination: Psychedelic Experiences and the Psychoanalysis of Self-Actualization, SUNY Press

- Merkur, Daniel (2007), Crucified with Christ: Meditations on the Passion, Mystical Death, and the Medieval : Invention of Psychotherapy, SUNY Press

- Merkur, Daniel (2014), The Formation of Hippie Spirituality: 1. Union with God. In: J. Harold Ellens (ed.), "Seeking the Sacred with Psychoactive Substances: Chemical Paths to Spirituality and to God", ABC-CLIO

- Nour, M.; Evans, L.; Nutt, D.; Carhart-Harris, R. (2016), "Ego-Dissolution and Psychedelics: Validation of the Ego-Dissolution Inventory (EDI)", Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, doi:10.3389/fnhum.2016.00269

- Park, Jin Y. (2006), Buddhisms and Deconstructions, Rowman & Littlefield

- Phipps, Carter (2001), "Self-Acceptance or Ego Death?", What is Enlightenment?, 17: 36– 41

- Plotkin, Bill (2010), Nature and the Human Soul: Cultivating Wholeness and Community in a Fragmented World, New World Library

- Reynolds, John Myrdhin (1989), Self-Liberation Through Seeing With Naked Awareness, Station Hill Press

- Rindfleisch, Jennifer (2007), "The Death of the Ego in East-Meets-West Spirituality: Diverse Views From Prominent Authors", Zygon, 42 (1)

- Roberts, Bernadette (2004), What is self? A Study of the Spiritual Journey in Terms of Consciousness, Sentient Publications

- Rosen, Larry H. (1998), Archetypes of Transformation: Healing the Self/Other Split Through Active Omagination. In: Cooke et al (eds.), "The Fantastic Other: An Interface of Perspectives, Volume 11", Rodopi

- Safran, Jeremy D. (2012), Psychoanalysis and Buddhism: An Unfolding Dialogue, Wisdom Publications Inc.

- Sekida (translator), Katsuki (1996), Two Zen Classics. Mumonkan, The Gateless Gate. Hekiganroku, The Blue Cliff Records. Translated with commentaries by Katsuki Sekida, New York / Tokyo: Weatherhill

- Shore, Jeff (2004), What is self? Foreword by Jeff Shore. In: Bernadette Roberts (2004), "What is self? A Study of the Spiritual Journey in Terms of Consciousness", Sentient Publications

- Stephenson, William (2011), Gonzo Republic: Hunter S. Thompson's America, Bloomsbury Publishing USA

- Taylor, Bron (2008), Encyclopedia of Religion and Nature, A&C Black

- Ventegodt, Soren; Merrick, Joav (2003), "Measurement of Quality of Life VII. Statistical Covariation and Global Quality of Life Data: The Method of Weight-Modified Linear Regression", The Scientific World Journal, 3: 1020–1029, doi:10.1100/tsw.2003.89

- Waddell, Norman (2010), Introduction to Wild Ivy: The Spiritual Autobiography of Zen Master Hakuin, Shambhala Publications

- Welwood, John (2014), Toward a Psychology of Awakening: Buddhism, Psychotherapy, and the Path of Personal and Spiritual Transformation, Shambhala Publications

- White, Richard (2012), The Heart of Wisdom: A Philosophy of Spiritual Life, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers

- Yoshizawa, Katsuhiro (2010), The Religious Art of Zen Master Hakuin, Counterpoint Press

Web-sources

- 1 2 Editor: Mark, Self-Acceptance or Ego Death, Nondual Highlights Issue #1694 Saturday, January 31, 2004

- ↑ Michael Hoffman (2006-2007), The Entheogen Theory of Religion and Ego Death

- ↑ Zennist (January 12, 2010), The murkiness of egolessness

- ↑ Sinzen Young, The Dark Night

- 1 2 Tomas Rocha (2014), The Dark Knight of the Soul, part 1, The Atlantic

- ↑ Tomas Rocha (2014), The Dark Knight of the Soul, part 2, The Atlantic

- ↑ Brad Warner (Saturday, July 09, 2011), The Psychedelic Experience, hardcorezen.blogpsot.nl

Further reading

- Penner, James (2014), Timothy Leary: The Harvard Years: Early Writings on LSD and Psilocybin with Richard Alpert, Huston Smith, Ralph Metzner, and others, Inner Traditions / Bear & Co

- Henderson, Joseph Lewis; Oakes, Maud (1963), The Wisdom of the Serpent: The Myths of Death, Rebirth, and Resurrection, Princeton University Press

- Grof, Stanislav; Halifax, Joan (1977), The Human Encounter With Death (PDF), Dutton

- Merton, Thomas (2010), Transcendent Experience. Who Is It Who Has Transcendent Experiences? In: Merton, "Zen and the Birds of Appetite", New Directions Publishing

- Low, David (1990), "The Nonduality of Life and Death: A Buddhist View of Repression", Philosophy East and West, 40 (2): 151–174, doi:10.2307/1399226

External links

- Psychedelics

- The Effect of LSD on the Ego

- psychonaut.com, What is Ego-death ??? descriptions of experiences of ego death caused by psychedelics

- Psychedelics and spirituality/religion

- Spirituality

- Osho, "Ego - The False Center"

- The Almaasery, "Ego Death"

- Dr. Sara Kendall Gordon (Pralaya) (2013), Reconsidering Ego Death and the False Self, Undivided, The Online Journal of Nonduality and Psychology

- Self-awakening

- Depersonalisation

- Depersonalisation versus Enlightenment talk by Shinzen Young, and first-hand narratives of experiences of DP/DR and "non-ego"

- You Do NOt Exist: A Look Inside Ego Death

- Depersonalization/Derealization Disorder or Zen/Emptiness Sickness - Part One

- Self-help

- Fashion