Elizabeth Seymour, Duchess of Somerset

| Elizabeth Seymour Duchess of Somerset | |

|---|---|

|

Lady Elizabeth Percy (Duchess of Somerset), painted in 1713 by Godfrey Kneller (1646/9-1723); collection of Petworth House | |

| Born |

26 January 1667 Petworth House, Sussex |

| Died |

24 November 1722 (aged 55) Northumberland House, London |

| Nationality |

|

| Occupation | Courtier and politician |

| Spouse(s) |

(1) Henry Cavendish, Earl of Ogle (c.1659–1680) (2) Thomas Thynne(1648–1682) (3) Charles Seymour, 6th Duke of Somerset (1662–1748) |

| Children |

Algernon Seymour, 7th Duke of Somerset (1684–1750) Lady Elizabeth Seymour (1685–1734) Lady Catherine Seymour (d. 1731) Lady Anne Seymour (d. 1722) |

| Parent(s) | Joceline Percy, 11th Earl of Northumberland (1644–1670) and Elizabeth Wriothesley (d. 1690) |

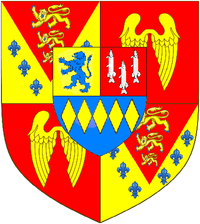

Elizabeth Seymour, Duchess of Somerset and suo jure Baroness Percy (26 January 1667 – 24 November 1722) was a great heiress. She was born Lady Elizabeth Percy, the only surviving child and sole heiress of Joceline Percy, 11th Earl of Northumberland (1644-1670). Lady Elizabeth was one of the closest personal friends of Queen Anne, which led Jonathan Swift to direct at her one of his sharpest satires, The Windsor Prophecy in which she was named "Carrots."

Marriages & progeny

She married thrice, producing progeny by the third marriage only:

Henry Cavendish, Earl of Ogle

At the age of 12 she married firstly on 27 March 1679, the 20 year-old Henry Cavendish, Earl of Ogle (1659 – 1 November 1680), the only son and heir of Henry Cavendish, 2nd Duke of Newcastle, who in accordance with the marriage settlement adopted the surname of Percy in lieu of his patronymic.[1] However he died the following year and was buried in the parish church at the Percy seat of Petworth. Without progeny, although due to her young age the marriage probably had not been consummated.

Thomas Thynne

On 15 November 1681 at the age of 14, she married secondly to Thomas Thynne (d.1682) of Longleat, Wiltshire, known due to his great income as "Tom of Ten Thousand", a relative of Thomas Thynne, 1st Viscount Weymouth. He was murdered the following February by a gang on the order of Swedish Count Karl Johann von Königsmark, who had started to pursue her following rumour that her marriage was unhappy. For the rest of her life her enemies spread the story that she had incited the murder. The actual murderers were hanged, but Königsmark was acquitted of being an accessory to the crime, despite widespread public feeling against him. Without progeny.

Charles Seymour, 6th Duke of Somerset

Five months after the death of Thomas Thynne, at the age of 15 she married on 30 May 1682 the 20 year-old Charles Seymour, 6th Duke of Somerset, of Marlborough Castle in Wiltshire, and so became Duchess of Somerset. Soon after the marriage he rebuilt in palatial style her father's principal seat Petworth House in Sussex. She was Mistress of the Robes to Queen Anne from 1710 to 1714. The marriage is said to have been unhappy: while she brought the Duke great wealth, it was said that she received neither affection nor gratitude in return. By the Duke she had progeny as follows:

- Charles Somerset, Earl of Hereford (baptized 22 March 1683-died before 26 Aug 1683), who died an infant in his first year.

- Algernon Seymour, 7th Duke of Somerset (11 November 1684 – 7 February 1749), eldest surviving son and heir. His only daughter and sole-heiress Lady Elizabeth Seymour, suo jure Baroness Percy, together with her husband Sir Hugh Smithson, 4th Baronet (d.1786) (who in 1749 adopted the surname Percy and in 1766 was created Duke of Northumberland) inherited half the great Percy estates including Alnwick Castle and Syon House.

- Lady Elizabeth Seymour (1685 – 2 April 1734), wife of Henry O'Brien, 8th Earl of Thomond (1688-1741), without progeny. His chosen heir was her younger nephew Percy Wyndham-O'Brien, 1st Earl of Thomond (c. 1713–1774) of Shortgrove, Essex, who adopted the surname O'Brien and was elevated to the peerage.

- Lady Catherine Seymour (1693 – 9 April 1731), wife of Sir William Wyndham, 3rd Baronet (c.1688-1740) of Orchard Wyndham in Somerset. Her eldest son was Charles Wyndham, 2nd Earl of Egremont (1710-1763), who inherited half of the great Percy estates including Petworth House and Egremont Castle.

- Lady Anne Seymour (1709 – 27 November 1722), died young.

Political influence

The Duke and Duchess were among the Queen's oldest friends, with whom she had taken refuge in 1692 after a violent quarrel with William III and Mary.[3] Like Marlborough before him, Somerset used his wife's position as confidante to advance his career. Both of them became the target of violent verbal attacks, especially from Swift who hoped to influence the Queen through Abigail Masham, the obvious rival for the position of confidante. Apparently against Mrs. Masham's wishes he published a violent diatribe, The Windsor Prophecy, against the Duchess, referred to as "Carrots" (a common nickname derived from the Duchess' red hair). Swift explicitly accused the Duchess of having conspired to murder her second husband, and wildly suggested that she might poison the Queen "I have been told, they assassin when young and poison when old".[4] The Queen was outraged; always a bad enemy to make, from then on she refused to consider Swift for preferment to a bishopric: even his appointment as Dean of St. Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin, was made against her strongly expressed wishes (she did not have power to veto it). Ignoring the gossip, she insisted on retaining the Duchess in her household.

The Duke's pride and arrogance eventually wore out the Queen's patience and he was dismissed from his court offices early in 1712. The Queen's doctor, Sir David Hamilton, advised her to keep the Duchess in her service "for her own quiet", and the Queen agreed. The Duchess remained with the Queen to the end of Anne's life, by which time Lord Dartmouth described her as "much the greatest favourite". During the Queen's painful last days, Elizabeth's calm and soothing manner is said to have brought some comfort, whereas Mrs. Masham was in a state of hysterics.

Reputation

Elizabeth's influence on the Queen, together with her colourful past, made her many enemies. Like her third husband she seems to have been proud, although Lord Dartmouth called her "the best bred as well as the best born person in England".[5] She showed great skill in dealing with the Queen, her secret, it was said, being never to press the Queen to do anything for her, in contrast to Abigail Masham who constantly asked for favours. She was known as a shrewd observer of Court life and a notorious gossip; even the Queen, who was fond of her, called her "one of the most observing, prying ladies in England".

Estates and residences

Lady Elizabeth Percy brought immense estates to her husbands and in addition her residences: Alnwick Castle, Petworth House, Syon House and Northumberland House in London.[6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19]

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Elizabeth Seymour, Duchess of Somerset | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References and notes

- ↑ Collins, Arthur, Peerage of England, Volume 4, London, 1756, p.186

- ↑ Per photograph in Nicholson, Nigel, Great Houses of Britain, London, 1978, p.166

- ↑ Gregg, E.G. ( 1980 ) Queen Anne

- ↑ Gregg: Queen Anne

- ↑ Gregg

- ↑ Cokayne et al., The Complete Peerage, volume I, p.212

- ↑ Cokayne et al., The Complete Peerage, volume I, p.90

- ↑ Cokayne et al., The Complete Peerage, volume XII, p.488

- ↑ The Diary of John Evelyn

- ↑ The Letters of Horace Walpole

- ↑ Calendar of state papers, domestic series, 1682, 49

- ↑ Cokayne et al., The Complete Peerage, volume XII, p.586

- ↑ See

- ↑ Burke, John – "Somerset, Duke of" and "Northumberland, Earl of":Burke's Peerage

- ↑ de Fonblanque, E. B.,Annals of the house of Percy, from the conquest to the opening of the nineteenth century, p.507

- ↑ The diary of Sir David Hamilton, 1709–1714, p.49, edited by Roberts, P. (1975)

- ↑ A Journal to Stella, Swift, Jonathan, edited by Williams, H. (1948)

- ↑ Holmes, G. S., British politics in the age of Anne (1967)

- ↑ Life and Letters of Sir George Savile, p.244

Sources

- British Library, Blenheim manuscripts

- Bucholz, R. O. "Seymour (née Percy), Elizabeth, duchess of Somerset (1667–1722), courtier and politician". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 6 August 2007.

- Bucholz, R. O. (1993). The Augustan court: Queen Anne and the decline of court culture.

- Chatsworth House, Devonshire manuscripts

- Cokayne, George (1887–1898). The Complete Peerage. Sutton, Alan.

- Gregg, E. G. (1980). Queen Anne.

- Holmes, G. S. (1967). British politics in the age of Anne.

- Snyder, H. L. (1975). The Marlborough–Godolphin correspondence.

- West Sussex Record Office, Petworth House archives, Somerset papers

| Court offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by The Duchess of Marlborough |

Mistress of the Robes to Queen Anne 1711–1714 |

Succeeded by — |

| Preceded by The Duchess of Marlborough |

Mistress of the Robes 1711–1714 |

Succeeded by Elizabeth Sackville, Duchess of Dorset |