Entasis

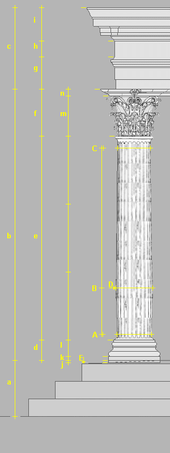

In architecture, entasis is the application of a convex curve to a surface for aesthetic purposes. Its best-known use is in certain orders of Classical columns that curve slightly as their diameter is decreased from the bottom upwards.

Etymology

The word is used by the Roman architectural historian Vitruvius,[1] and derives from the Greek word εντείνω (enteino), "to stretch or strain tight".

Examples

Probably the first use of entasis was in the construction of the Egyptian pyramids, but it can also be observed in Classical period Greek column designs, for example in the Doric-order temples in Segesta, Selinus, Agrigento and Paestum. It was used less in Hellenistic and Roman period architecture. The Roman temples built during these periods were higher than those of the Greeks, with longer and thinner columns. Chinese carpenters of the Song Dynasty followed the designs in the AD 1103 Yingzao Fashi (Treatise on Architectural Methods or State Building Standards) which specified straight columnns or with an entasis on the upper third of the shaft.[2] Noted architects such as the Renaissance master Andrea Palladio also used it in their buildings.

Entasis was often a feature of Inca walls and double-jamb doorways, where they also act to counteract the optical illusion that would make the doorway appear narrower in the middle of its slope than it really would be.[3]

It can also be seen in the sloping or battered walls of some Tibetan monastery and fortress architecture, also in Bhutan. The lower part, approximately one third, has a slight inward curve, the higher parts are straight. If one builds the whole wall as a straight, sloping surface, it appears to bulge outwards. An example in Bhutan is the Dobji dzong. When some collapsed walls of the Punakha dzong were rebuilt around 1996, this wisdom about optical perceptions appears to have been forgotten and, being straight, they appear to bulge. Chris Butters, author of The Treasure Revealer of Bhutan, Bibliotheca Himalayica 1995.

Purpose

The early Classical builders did not leave an explanation of their reasons for using entasis, and there are several differing opinions as to its purpose:

An early-articulated and still widespread view, espoused by Hero of Alexandria, is that entasis corrects the optical illusion of concavity in the columns which the fallible human eye would create if a correction were not made.[4] This view, however, does not explain the case of one well-known example, Paestum, where the entasis is so pronounced that it creates an obvious curvature, not an illusion of straightness.

Some descriptions of entasis[5] state simply that the technique was an enhancement applied to the more primitive conical columns to make them appear more substantial. Other descriptions argue that the technique emphasizes the substantiality of not the columns themselves but rather some other part or of the building as a whole. Yale architectural historian Vincent Scully argues that entasis emphasizes the weight of a building's roof by making the building's columns appear to buckle under the pressure distributed among them. Danish architect Steen Eiler Rasmussen believed that the effect represented strength by imitating the swelling of a strained muscle,[6] a theory which accords well with the etymology of the word, from the Greek meaning "to strain".[7]

It has also been argued that a "stunted cycloid" column that bulges in the middle is structurally stronger than is a column whose diameter changes according to a linear progression. However it is unclear whether the early Greeks could have known this.[8] If the column originally was a reference to the palm tree, the "bulge" is an accurate representation of the palm tree trunk.

Literature

- Thomä, Walter (1915). Die Schwellung der Säule (Entasis) bei den Architekturtheoretikern bis in das XVIII. Jahrhundert (in German). Dresden.

References

- ↑ Vitruvius. On Architecture. 3.3.13. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- ↑ Liang, Sicheng, and Wilma Fairbank, ed.. A pictorial history of Chinese architecture: a study of the development of its structural system and the evolution of its types. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1984. 17.

- ↑ Protzen, Jean-Pierre. "Inca Architecture" in The Inca World, Laura Laurencich Minelli (ed). University of Oklahoma Press, 2000, pp. 196-197.

- ↑ Hero of Alexandria, Horoi ton geometrias onomaton, 135, 14: "Thus, since a cylindrical column would, when looked at, seem irregularly narrower in the middle, he makes this part of it wider" (translation given by Ralph Hancock, The Department of Greek and Latin at The Ohio State University)

- ↑ entasis, article by Anthony Rich, Jun. B.A. of Caius College, Cambridge, on p461 of William Smith, D.C.L., LL.D.: A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, John Murray, London, 1875.

- ↑ Steen Eiler Rasmussen, Experiencing Architecture, The MIT Press, 1959, p. 37.

- ↑ "entasis", Oxford English Dictionary, Second Edition 1989

- ↑ Peter Thompson et al., "Entasis: architectural illusion compensation, aesthetic preference or engineering necessity?", Journal of Vision, Volume 7, Number 9, ISSN 1534-7362 - abstract argues against traditional explanations for entasis and mentions possible engineering reason