Corporate tax in the United States

| This article is part of a series on |

| Taxation in the United States of America |

|---|

|

|

|

Corporate tax is imposed in the United States at the federal, most state, and some local levels on the income of entities treated for tax purposes as corporations. Federal tax rates on corporate taxable income vary from 15% to 35%. State and local taxes and rules vary by jurisdiction, though many are based on federal concepts and definitions. Taxable income may differ from book income both as to timing of income and tax deductions and as to what is taxable. Corporations are also subject to a federal Alternative Minimum Tax and alternative state taxes. Like individuals, corporations must file tax returns every year. They must make quarterly estimated tax payments. Controlled groups of corporations may file a consolidated return.

Some corporate transactions are not taxable. These include most formations and some types of mergers, acquisitions, and liquidations. Shareholders of a corporation are taxed on dividends distributed by the corporation. Corporations may be subject to foreign income taxes, and may be granted a foreign tax credit for such taxes.

Shareholders of most corporations are not taxed directly on corporate income, but must pay tax on dividends paid by the corporation. However, shareholders of S Corporations and mutual funds are taxed currently on corporate income, and do not pay tax on dividends.

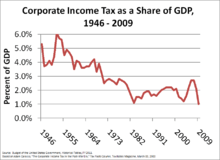

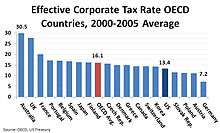

The United States has the third highest general top marginal corporate income tax rate in the world at 39.1 percent (consisting of the 35% federal rate and a combined state rate), exceeded only by Chad and the United Arab Emirates .[1] However, the average corporate tax rate in 2011 dipped to 12.1%, its lowest level since before World War I, largely due to the great recession and a bonus depreciation tax break.[2]

Overview

Corporate income tax is imposed at the federal level[3] on all entities treated as corporations (see Entity classification below), and by 47 states and the District of Columbia. Certain localities also impose corporate income tax. Corporate income tax is imposed on all domestic corporations and on foreign corporations having income or activities within the jurisdiction. For federal purposes, an entity treated as a corporation and organized under the laws of any state is a domestic corporation.[4] For state purposes, entities organized in that state are treated as domestic, and entities organized outside that state are treated as foreign.[5]

Some types of corporations (S corporations, mutual funds, etc.) are not taxed at the corporate level, and their shareholders are taxed on the corporation's income as it is recognized.[6] Corporations which are not S Corporations are known as C Corporations.

Domestic corporations are taxed on their worldwide income at the federal and state levels.[7] Corporate income tax is based on net taxable income as defined under federal or state law. Generally, taxable income for a corporation is gross income (business and possibly non-business receipts less cost of goods sold) less allowable tax deductions. Certain income, and some corporations, are subject to a tax exemption. Also, tax deductions for interest and certain other expenses paid to related parties are subject to limitations.

Corporations may choose their tax year. Generally, a tax year must be 12 months or 52/53 weeks long. The tax year need not conform to the financial reporting year, and need not coincide with the calendar year, provided books are kept for the selected tax year.[8] Corporations may change their tax year, which may require Internal Revenue Service consent.[9] Most state income taxes are determined on the same tax year as the federal tax year.

| Table of Corporate Income Taxes As a Percentage of GDP For the US and OECD Countries, 2008[10][11] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Tax/GDP | Country | Tax/GDP |

| Norway | 12.4 | Switzerland | 3.3 |

| Australia | 5.9 | Netherlands | 3.2 |

| Luxembourg | 5.1 | Slovak Rep. | 3.1 |

| New Zealand | 4.4 | Sweden | 3.0 |

| Czech Rep. | 4.2 | France | 2.9 |

| South Korea | 4.2 | Ireland | 2.8 |

| Japan | 3.9 | Spain | 2.8 |

| Italy | 3.7 | Poland | 2.7 |

| Portugal | 3.7 | Hungary | 2.6 |

| Britain | 3.6 | Austria | 2.5 |

| Finland | 3.5 | Greece | 2.5 |

| Israel | 3.5 | Slovenia | 2.5 |

| OECD avg. | 3.5 | United States | 2.0 |

| Belgium | 3.4 | Germany | 1.9 |

| Canada | 3.4 | Iceland | 1.9 |

| Denmark | 3.3 | Turkey | 1.8 |

Federal corporate income tax is imposed at graduated rates. The lower rate brackets apply to lower rates of income when compared to higher tax brackets that coincide with higher rates of taxable income. All taxable income is subject to tax at 34% or 35% where taxable income exceeds $335,000. Tax rates imposed below the federal level vary widely by jurisdiction, from under 1% to over 16%. State and local income taxes are allowed as tax deductions in computing federal taxable income.

Groups of companies are permitted to file single returns for the members of a controlled group or unitary group, known as consolidated returns, at the federal level, and are allowed or required to do so by certain states. The consolidated return reports the members' combined taxable incomes and computes a combined tax. Where related parties do not file a consolidated return in a jurisdiction, they are subject to transfer pricing rules. Under these rules, tax authorities may adjust prices charged between related parties.

Shareholders of corporations are taxed separately upon the distribution of corporate earnings and profits as a dividend. Tax rates on dividends are at present lower than on ordinary income for both corporate and individual shareholders. To ensure that shareholders pay tax on dividends, two withholding tax provisions may apply: withholding tax on foreign shareholders, and “backup withholding” on certain domestic shareholders.

Corporations must file tax returns in all U.S. jurisdictions imposing an income tax. Such returns are a self-assessment of tax. Corporate income tax is payable in advance installments, or estimated payments, at the federal level and for many states.

Corporations may be subject to withholding tax obligations upon making certain varieties of payments to others, including wages and distributions treated as dividends. These obligations are generally not the tax of the corporation, but the system may impose penalties on the corporation or its officers or employees for failing to withhold and pay over such taxes.

State and local income taxes

Nearly all of the states and some localities impose a tax on corporation income. The rules for determining this tax vary widely from state to state. Many of the states compute taxable income with reference to federal taxable income, with specific modifications. The states do not allow a tax deduction for income taxes, whether federal or state. Further, most states deny tax exemption for interest income that is tax exempt at the federal level.

Most states tax domestic and foreign corporations on taxable income derived from business activities apportioned to the state on a formulary basis. Many states apply a "throw back" concept to tax domestic corporations on income not taxed by other states. Tax treaties do not apply to state taxes.

Under the U.S. Constitution, states are prohibited from taxing income of a resident of another state unless the connection with the taxing state reach a certain level (called “nexus”).[13] Most states do not tax non-business income of out of state corporations. Since the tax must be fairly apportioned, the states and localities compute income of out of state corporations (including those in foreign countries) taxable in the state by applying formulary apportionment to the total business taxable income of the corporation. Many states use a formula based on ratios of property, payroll, and sales within the state to those items outside the state.

History

The first federal income tax was enacted in 1861, and expired in 1872, amid constitutional challenges. A corporate income tax was enacted in 1894, but a key aspect of it was shortly held unconstitutional. In 1909, Congress enacted an excise tax on corporations based on income. After ratification of the Sixteenth amendment to the U.S. Constitution, this became the corporate provisions of the federal income tax.[14] Amendments to various provisions affecting corporations have been in most or all revenue acts since. Corporate tax provisions are incorporated in Title 26 of the United States Code, known as the Internal Revenue Code. The present rate of tax on corporate income was adopted in the Tax Reform Act of 1986.[15]

In 2010, corporate tax revenue constituted about 9% of all federal revenues or 1.3% of GDP.[16]

Entity classification

Business entities may elect to be treated as corporations taxed at the entity and member levels or as "flow through" entities taxed only at the member level. However, entities organized as corporations under U.S. state laws and certain foreign entities are treated, per se, as corporations, with no optional election. The Internal Revenue Service issued the so-called “check-the-box” regulations in 1997 under which entities may make such choice by filing Form 8832. Absent such election, default classifications for domestic and foreign business entities, combined with voluntary entity elections to opt out of the default classifications (except in the case of “per se corporations” (as defined below)).[17] If an entity not treated as a corporation has more than one equity owner and at least one equity owner does not have limited liability (e.g., a general partner), it will be classified as a partnership (i.e., a pass-through), and if the entity has a single equity owner and the single owner does not have limited liability protection, it will be treated as a disregarded entity (i.e., a pass-through).

Some entities treated as corporations may make other elections that enable corporate income to be taxed only at the shareholder level, and not at the corporate level. Such entities are treated similarly to partnerships. The income of the entity is not taxed at the corporate level, and the members must pay tax on their share of the entity's income. These include:

- S Corporations, all of whose shareholders must be U.S. citizens or resident individuals; other restrictions apply. The election requires the consent of all shareholders. If a corporation is not an S corporation from its formation, special rules apply to the taxation of income earned (or gains accrued) before the election.

- Regulated investment companies (RICs), commonly referred to as mutual funds.

- Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs).

Taxable income

Determinations of what is taxable and at what rate are made at the federal level based on U.S. tax law. Many but not all states incorporate federal law principles in their tax laws to some extent. Federal taxable income equals gross income[18] (gross receipts and other income less cost of goods sold) less tax deductions.[19] Gross income of a corporation and business deductions are determined in much the same manner as for individuals.[20] All income of a corporation is subject to the same federal tax rate. However, corporations may reduce other federal taxable income by a net capital loss[21] and certain deductions are more limited.[22] Certain deductions are available only to corporations. These include deductions for dividends received[23] and amortization of organization expenses.[24] Some states tax business income of a corporation differently than nonbusiness income.[25]

Principles for recognizing income and deductions may differ from financial accounting principles. Key areas of difference include differences in the timing of income or deduction, tax exemption for certain income, and disallowance or limitation of certain tax deductions.[26] IRS rules require that these differences be disclosed in considerable detail for non-small corporations on Schedule M-3 to Form 1120.

Tax rates

Federal tax rates

For regular income tax purposes, a system of graduated marginal tax rates is applied to all taxable income, including capital gains. Through 2015, the marginal tax rates on a corporation's taxable income are as follows:

| Taxable Income ($) | Tax Rate[27] |

|---|---|

| 0 to 50,000 | 15% |

| 50,000 to 75,000 | $7,500 + 25% Of the amount over 50,000 |

| 75,000 to 100,000 | $13,750 + 34% Of the amount over 75,000 |

| 100,000 to 335,000 | $22,250 + 39% Of the amount over 100,000 |

| 335,000 to 10,000,000 | $113,900 + 34% Of the amount over 335,000 |

| 10,000,000 to 15,000,000 | $3,400,000 + 35% Of the amount over 10,000,000 |

| 15,000,000 to 18,333,333 | $5,150,000 + 38% Of the amount over 15,000,000 |

| 18,333,333 and up | 35% |

This rate structure produces a flat 34% tax rate on incomes from $335,000 to $10,000,000, gradually increasing to a flat rate of 35% on incomes above $18,333,333.

State income tax rates

| State Corporate Income Tax Rates in the United States in 2010[28] | ||

|---|---|---|

| State | Tax Rate(s) | Tax Bracket(s) |

| Alabama (a) | 6.5% | $0 |

| Alaska | 1% 2% |

$0

$10K |

| Arizona | 6.968% | $0 |

| Arkansas (h) | 1% 2% |

$0

$3K |

| California (g) | 8.84% | $0 |

| Colorado | 4.63% | $0 |

| Connecticut | 7.5% | $0 |

| Delaware | 8.7% | $0 |

| Florida (g) | 5.5% | $0 |

| Georgia | 6% | $0 |

| Hawaii | 4.4% 5.4% |

$0

$25K |

| Idaho | 7.6% | $0 |

| Illinois | 7.3% | $0 |

| Indiana | 8.5% | $0 |

| Iowa | 6% 8% 10% 12% |

$0

$25K |

| Kansas [29] | 3% | $0 |

| Kentucky | 4% 5% 6% |

$0

$50K |

| Louisiana | 4% 5% 6% 7% 8% |

$0

$25K |

| Maine (g) | 3.5% 7.93% 8.33% 8.93% |

$0

$25K |

| Maryland | 8.25% | $0 |

| Massachusetts | 8.8% | $0 |

| Michigan (b), (f), (g) | 4.95% | $0 |

| Minnesota (g) | 9.8% | $0 |

| Mississippi | 3% 4% 5% |

$0

$5K |

| Missouri (i) | 6.25% | $0 |

| Montana (j) | 6.75% | $0 |

| Nebraska | 5.58% 7.81% |

$0

$100k |

| Nevada | None | None |

| New Hampshire (k) | 8.5% | $0 |

| New Jersey (c), (g) | 9% | $0 |

| New Mexico | 4.8% 6.4% 7.6% |

$0

$500K |

| New York (a), (f), (g), (h) | 7.1% | $0 |

| North Carolina | 6.9% | $0 |

| North Dakota (j) | 2.1% 5.3% 6.4% |

$0

$25K |

| Ohio (d), (f) | 0.26% | $0 |

| Oklahoma | 6% | $0 |

| Oregon (e) | 6.6% 7.9% |

$0

$250K |

| Pennsylvania (f), (g) | 9.99% | $0 |

| Rhode Island | 9% | $0 |

| South Carolina | 5% | $0 |

| South Dakota | None | None |

| Tennessee | 6.5% | $0 |

| Texas (l) | Franchise Tax rate | Franchise Tax rate |

| Utah (g) | 5% | $0 |

| Vermont | 6% 7% 8.5% |

$0

$10K |

| Virginia | 6% | $0 |

| Washington (g) | None | None |

| West Virginia | 8.5% | $0 |

| Wisconsin | 7.9% | 0 |

| Wyoming | None | None |

| District of Columbia | 9.975% | $0 |

|

Notes: The rates above are for regular corporate taxes based on income (including those called franchise taxes) and exclude the effect of alternative taxes and minimum taxes. Most states have a minimum income or franchise tax. The above rates generally apply to entities treated as corporations other than S Corporations and financial institutions, which may be subject to different rates of tax. Tax rates are before credits and reductions for corporations operating in certain parts of the state. (a) Excludes the effect of graduated tax rates based on level of income. (b) The Michigan Business Tax applies to incorporated and unincorporated businesses, and is based on alternative measure of income that may not relate to net income. (c) Businesses with an entire net income greater than $100K pay 9% in all taxable income, companies with entire net income greater than $50K and less than or equal to $100K pay 7.5% on all taxable income, and companies with entire net income less than or equal to $50K pay 6.5% on all taxable income. (d) A tax on gross receipts, the commercial activity tax (CAT), was phased in from 2005 to 2008 while the corporate franchise tax (CFT, Ohio's corporate net income tax) was phased out. Beginning April 1, 2009, the CAT rate was fully phased in at 0.26%. (e) The top income tax rate (7.9% on income over $250K) applies to tax years beginning on or after January 1, 2009, and before January 1, 2011. (f) Excludes local corporate income tax. (g) Excludes the effect of alternative tax bases, such as sales or assets. (h) Other tax rates may apply to certain corporations. (i) Missouri allows a deduction for federal income tax payments, reducing the effective state tax rate. (j) A higher rate applies if the corporation elects "water's edge" apportionment. (k) Also applies to unincorporated entities. (l) While not called an income tax, Texas imposes a franchise tax at the higher of a tax based on capital or a graduated tax based on income. | ||

The table to the right lists the tax rates on corporate income applied by each state, but not by local governments within states. Because state and local taxes are deductible expenses for federal income tax purposes, the effective tax rate in each state is not a simple addition of federal and state tax rates.

It should be noted that while a state may not levy a corporate income tax, they may impose other taxes that are similar. For example, Washington state does not have an income tax but levies a B&O (business and occupation tax) which is arguably a larger burden because the B&O tax is calculated as a percentage of revenue rather than a percentage of net income, like the corporate income tax. This means even loss-making enterprises are required to pay the tax.

Tax credits

Corporations, like other businesses, may be eligible for various tax credits which reduce federal, state or local income tax.[30] The largest of these by dollar volume is the federal foreign tax credit.[31][32] This credit is allowed to all taxpayers for income taxes paid to foreign countries. The credit is limited to that part of federal income tax before other credits generated by foreign source taxable income. The credit is intended to mitigate taxation of the same income to the same taxpayer by two or more countries, and has been a feature of the U.S. system since 1918. Other credits include credits for certain wage payments, credits for investments in certain types of assets including certain motor vehicles, credits for use of alternative fuels and off-highway vehicle use, natural resource related credits, and others. See, e.g., the Research & Experimentation Tax Credit.

Tax deferral

Deferral is one of the main features of the worldwide tax system that allows U.S. multinational companies to delay paying taxes on foreign profits. Under U.S. tax law, companies are not required to pay U.S. tax on their foreign subsidiaries’ profits for many years, even indefinitely until the earnings are returned to U.S. Therefore, it is one of the main reasons that U.S. corporations pay low taxes, even though the corporate tax rate in the U.S. is one of the highest rates (35%) in the world.

Deferral is beneficial for U.S. companies to raise the cost of capital relatively to their foreign-based competitors. Their foreign subsidiaries can reinvest their earnings without incurring additional tax that allows them to grow faster. It is also valuable to U.S. corporations with global operations, especially for corporations with income in low-tax countries. Some of the largest and most profitable U.S. corporations pay exceedingly low tax rates[33] through their use of subsidiaries in so-called tax haven countries. Eighty-three of the United States’s 100 biggest public companies have subsidiaries in countries that are listed as tax havens or financial privacy jurisdictions, according to the Government Accountability Office.[34]

| United States Companies with Deferred Foreign Cash Balances That are Greater Than $5 Billion, 2012[35] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Company ($ Billions) | Total Cash | Foreign Cash | Foreign Cash % Total Cash |

| Apple | 110.2 | 74.0 | 67% |

| Microsoft | 59.5 | 50.0 | 89% |

| General Electric | 83.7 | >41.9 | >50% |

| Cisco | 46.7 | 41.7 | 89% |

| 49.3 | 25.7 | 48% | |

| Oracle | 29.7 | 25.1 | 84% |

| Johnson & Johnson | 24.5 | 24.5 | 100% |

| Pfizer | 24.0 | ~19.2 | ~80% |

| Amgen | 19.4 | 16.6 | 82% |

| Qualcomm | 26.6 | 16.5 | 62% |

| Coca-Cola | 15.8 | >13.9 | >88% |

| Dell | 13.9 | ~11.8 | ~85% |

| Merck | 19.5 | >9.2 | >47.2% |

| Medtronic | 8.9 | 8.3 | 93% |

| Hewlett-Packard | 8.1 | ~8.1 | ~100% |

| eBay | 8.0 | 7.0 | 88% |

| Wal-Mart | 6.6 | 5.6 | 85% |

However, tax deferral encourages U.S. companies to make job-creating investments offshore even if similar investments in the United States can be more profitable, absent tax considerations. Furthermore, companies try to use accounting techniques to record profits offshore by any way, even if they keep actual investment and jobs in the United States. This explains why U.S. corporations report their largest profits in low-tax countries like the Netherlands, Luxembourg, and Bermuda, though clearly that is not where most real economic activity occurs.[34]

Interest deduction limitations

A tax deduction is allowed at the federal, state and local levels for interest expense incurred by a corporation in carrying out its business activities. Where such interest is paid to related parties, such deduction may be limited.[36] The classification of instruments as debt on which interest is deductible or as equity with respect to which distributions are not deductible is highly complex and based on court-developed law. The courts have considered 26 factors in deciding whether an instrument is debt or equity, and no single factor predominates.[37]

Federal tax rules also limit the deduction of interest expense paid by corporations to foreign shareholders based on a complex calculation designed to limit the deduction to 50% of cash flow.[38] Some states have other limitations on related party payments of interest and royalties.

| Largest Tax Deductions, Credits, and Deferrals for Corporations 2005–2009[39] | Total Amount (2005–2009) (Billions of dollars) |

|---|---|

| Depreciation of equipment in excess of alternative depreciation system | 71.3 |

| Exclusion of interest on public purpose state and local government debt | 38.3 |

| Inventory property sales source rule exception | 30.9 |

| Expensing of research and experimental expenditures | 28.5 |

| Deferral of active income of controlled foreign corporations | 25.8 |

| Reduced rates for first $10,000,000 of corporate taxable income | 23.7 |

| Deduction for income attributable to domestic production activities | 19.8 |

| Tax credit for low-income housing | 17.5 |

| Exclusion of investment income on life insurance and annuity contracts | 12.8 |

| Tax credit for qualified research expenditures | 10.7 |

Other corporate events

U.S. rules provide that certain corporate events are not taxable to corporations or shareholders. Significant restrictions and special rules often apply. The rules related to such transactions are quite complex, and exist primarily at the federal level. Many of the states follow federal tax treatment for such events.

Formation

The formation of a corporation by controlling corporate or non-corporate shareholder(s) is generally a nontaxable event.[40] Generally, in tax free formations the tax attributes of assets and liabilities are transferred to the new corporation along with such assets and liabilities.

Example: John and Mary are United States residents who operate a business. They decide to incorporate for business reasons. They transfer assets of the business to Newco, a newly formed Delaware corporation of which they are the sole shareholders, subject to accrued liabilities of the business, solely in exchange for common shares of Newco. This transfer should not generally cause gain or loss recognition for John, Mary, or Newco.[41] Newco assumes John and Mary's tax basis in the assets it acquires.[42] If on the other hand Newco also assumes a bank loan in excess of the basis of the assets transferred less the accrued liabilities, John and Mary will recognize taxable gain for such excess.[43]

Acquisitions

Corporations may merge or acquire other corporations in a manner treated as nontaxable to either of the corporations and/or to their shareholders.[44] Generally, significant restrictions apply if tax free treatment is to be obtained. For example, Bigco acquires all of the shares of Smallco from Smallco shareholders in exchange solely for Bigco shares. This acquisition is not taxable to Smallco or its shareholders under U.S. tax law if certain requirements are met,[45] even if Smallco is then liquidated into or merged with Bigco.[46]

Reorganizations

In addition, corporations may change key aspects of their legal identity, capitalization, or structure in a tax free manner. Examples of reorganizations that may be tax free include mergers, liquidations of subsidiaries, share for share exchanges, exchanges of shares for assets, changes in form or place of organization, and recapitalizations.[47]

Advance tax planning might mitigate tax risks resulting from a business reorganization or potentially enhance tax savings.[48]

Distribution of earnings

Shareholders of corporations are subject to corporate or individual income tax when corporate earnings are distributed.[50] Such distribution of earnings is generally referred to as a dividend.

Dividends received by other corporations may be taxed at reduced rates, or exempt from taxation, if the dividends received deduction applies. Dividends received by individuals (if the dividend is a "qualified dividend") are taxed at reduced rates.[51] Exceptions to shareholder taxation apply to certain nonroutine distributions, including distributions in liquidation of an 80% subsidiary[52] or in complete termination of a shareholder's interest.[53]

If a corporation makes a distribution in a non-cash form, it must pay tax on any gain in value of the property distributed.[54]

The United States does not generally require withholding tax on the payment of dividends to shareholders. However, withholding tax is required if the shareholder is not a U.S. citizen or resident or U.S. corporation, or in some other circumstances (see Tax withholding in the United States).

Earnings and profits

U.S. corporations are permitted to distribute amounts in excess of earnings under the laws of most states under which they may be organized. A distribution by a corporation to shareholders is treated as a dividend to the extent of earnings and profits (E&P), a tax concept similar to retained earnings.[55] E&P is current taxable income, with significant adjustments, plus prior E&P reduced by distributions of E&P. Adjustments include depreciation differences under MACRS, add-back of most tax exempt income, and deduction of many non-deductible expenses (e.g., 50% of meals and entertainment).[56] Corporate distributions in excess of E&P are generally treated as a return of capital to the shareholders.[57]

Liquidation

The liquidation of a corporation is generally treated as an exchange of a capital asset under the Internal Revenue Code. If a shareholder bought stock for $300 and receives $500 worth of property from a corporation in a liquidation, that shareholder would recognize a capital gain of $200. An exception is when a parent corporation liquidates a subsidiary, which is tax-free so long as the parent owns more than 80% of the subsidiary. There are certain anti-abuse rules to avoid the engineering of losses in corporate liquidations.[58]

Foreign corporation branches

The United States taxes foreign (i.e., non-U.S.) corporations differently than domestic corporations.[59] Foreign corporations generally are taxed only on business income when the income is effectively connected with the conduct of a U.S. trade or business (i.e., in a branch). This tax is imposed at the same rate as the tax on business income of a resident corporation.[60]

The U.S. also imposes a branch profits tax on foreign corporations with a U.S. branch, to mimic the dividend withholding tax which would be payable if the business was conducted in a U.S. subsidiary corporation and profits were remitted to the foreign parent as dividends. The branch profits tax is imposed at the time profits are remitted or deemed remitted outside the U.S.[61]

In addition, foreign corporations are subject to withholding tax at 30% on dividends, interest, royalties, and certain other income. Tax treaties may reduce or eliminate this tax. This tax applies to a "dividend equivalent amount," which is the corporation's effectively connected earnings and profits for the year, less investments the corporation makes in its U.S. assets (money and adjusted bases of property connected with the conduct of a U.S. trade or business). The tax is imposed even if there is no distribution.

Consolidated returns

Corporations 80% or more owned by a common parent corporation may file a consolidated return for federal and some state income taxes.[62] These returns include all income, deductions, and credits of all members of the controlled group, generally expressed without intercompany eliminations. Some states allow or require a combined or consolidated return for U.S. members of a "unitary" group under common control and in related businesses. Certain transactions between group members may not be recognized until the occurrence of events for other members. For example, if Company A sells goods to sister Company B, the profit on the sale is deferred until Company B uses or sells the goods. All members of a consolidated group must use the same tax year.

Transfer pricing

Transactions between a corporation and related parties are subject to potential adjustment by tax authorities.[63] These adjustments may be applied to both U.S. and foreign related parties, and to individuals, corporations, partnerships, estates, and trusts.

Alternative taxes

United States federal income tax incorporates an alternative minimum tax. This tax is computed at a lower tax rate (20% for corporations), and imposed based on a modified version of taxable income. Modifications include longer depreciation lives assets under MACRS, adjustments related to costs of developing natural resources, and an addback of certain tax exempt interest.[64]

Corporations may also be subject to additional taxes in certain circumstances. These include taxes on excess accumulated undistributed earnings and personal holding companies[65] and restrictions on graduated rates for personal service corporations.[66]

Some states, such as New Jersey, impose alternative taxes based on measures other than taxable income. Among such measures are gross income, pipeline revenues, gross receipts, and various asset or capital measures. In addition, some states impose a tax on capital of corporations or on shares issued and outstanding. The U. S. state of Michigan previously taxed businesses on an alternative base that did not allow compensation of employees as a tax deduction and allowed full deduction of the cost of production assets upon acquisition.

Tax returns

Corporations subject to U.S. tax must file federal and state income tax returns.[68] Different tax returns are required at the federal and some state levels for different types of corporations or corporations engaged in specialized businesses. The United States has 13 variations on the basic Form 1120 for S corporations, insurance companies, Domestic International Sales Corporations, foreign corporations, and other entities. The structure of the forms and the imbedded schedules vary by type of form.

United States federal corporate tax returns require both computation of taxable income from components thereof and reconciliation of taxable income to financial statement income. Corporations with assets exceeding $10 million must complete a detailed 3 page reconciliation on Schedule M-3 indicating which differences are permanent (i.e., do not reverse, such as disallowed expenses or tax exempt interest) and which are temporary (e.g., differences in when income or expense is recognized for book and tax purposes).

Some state corporate tax returns have significant imbedded or attached schedules related to features of the state's tax system that differ from the federal system.[69]

Preparation of non-simple corporate tax returns can be time consuming. For example, the U.S. Internal Revenue Service states that the average time needed to complete Form 1120-S, for privately held companies electing flow through status, is over 56 hours, not including recordkeeping time.[70]

Federal corporate tax returns for most types of corporations are due by the 15th day of the third month following the tax year (March 15 for calendar year).[71] State corporate tax return due dates vary, but most are due either on the same date or one month after the federal due date. Extensions of time to file are routinely granted.[72]

Penalties may be imposed at the federal and state levels for late filing or non-filing of corporate income tax returns.[73] In addition, other substantial penalties may apply with respect to failures related to returns and tax return computations.[74] Intentional failure to file or intentional filing of incorrect returns may result in criminal penalties to those involved.[75]

Further reading

IRS Publication 542, Corporations

Standard tax texts

- Willis, Eugene; Hoffman, William H. Jr., et al: South-Western Federal Taxation, published annually. 2013 edition (cited above as Willis|Hoffman) ISBN 978-1-133-18955-8.

- Pratt, James W.; Kulsrud, William N., et al: Federal Taxation, updated periodically. 2013 edition ISBN 978-1-133-49623-6 (cited above as Pratt & Kulsrud).

- Fox, Stephen C., Income Tax in the USA, published annually. 2013 edition ISBN 978-0-985-18231-1

Treatises

- Bittker, Boris I. and Eustice, James S.: Federal Income Taxation of Corporations and Shareholders: abridged paperback ISBN 978-0-7913-4101-8 or as a subscription service. Cited above as Bittker & Eustice.

- Crestol, Jack; Hennessey, Kevin M.; and Yates, Richard F.: "Consolidated Tax Return : Principles, Practice, Planning, 1998 ISBN 978-0-7913-1629-0

- Kahn & Lehman. Corporate Income Taxation

- Healy, John C. and Schadewald, Michael S.: Multistate Corporate Tax Course 2010, CCH, ISBN 978-0-8080-2173-5 (also available as a multi-volume guide, ISBN 978-0-8080-2015-8)

- Hoffman, et al.: Corporations, Partnerships, Estates and Trusts, ISBN 978-0-324-66021-0

- Momburn, et al.: Mastering Corporate Tax, Carolina Academic Press, ISBN 978-1-59460-368-6

- Norton, Bob (2008). "Corporate Taxation". In David R. Henderson (ed.). Concise Encyclopedia of Economics (2nd ed.). Indianapolis: Library of Economics and Liberty. ISBN 978-0865976658. OCLC 237794267.

Government publications

- Keightley, Mark P. and Molly F. Sherlock: The Corporate Income Tax System: Overview and Options for Reform, Congressional Research Service, 2014.

See also

- Corporations in the United States

- List of corporations in the United States

- List of taxes paid yearly by corporations in the United States

References

- ↑ Puzzanghera, Jim (15 December 2015). "Corporate Income Tax Rates around the World, 2014". TaxFoundation.org. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ↑ "With Tax Break, Corporate Rate Is Lowest in Decades" Wall Street Journal, February 3, 2012

- ↑ Subtitle A of Title 26 of the United States Code, in particular 26 U.S.C. § 11, § 881, and § 882. For a thorough overview of federal income taxation of corporations, see Internal Revenue Service Publication 542, Corporations. See also Willis|Hoffman chapters 17-20, Pratt & Kulsrud chapters 19–21, Fox chapter 30 (each fully cited under Further reading). For purely corporate tax matters, the Bittker & Eustice treatise cited fully under Treatises is authoritative and has been cited by the Supreme Court.

- ↑ 26 U.S.C. § 7701(a)(4). Note that a sham entity may be ignored. See Pratt & Kulsrud 2005 p. 19-4.

- ↑ See, e.g., New York State Publication 20, Tax Guide for Business, page 8.

- ↑ For 2006, the Internal Revenue Service reported that approximately 6 million corporate returns were filed, of which more than 4 million were S corporations. See 2006 Statistics on Income, Corporation Income Tax Returns.

- ↑ 26 U.S.C. § 11, Pratt & Kulsrud 2005 pp. 3–4.

- ↑ 26 U.S.C. § 441. Also see IRS Publication 538 Accounting Methods and Periods.

- ↑ 26 U.S.C. § 442.

- ↑ Bartlett, Bruce (31 May 2011). "Are Taxes in the U.S. High or Low?". New York Times. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- ↑ http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?QueryId=21699#

- ↑ "Treasury Conference on Business Taxation and Global Competitiveness" (PDF). US Treasury. 23 July 2007. p. 42.

- ↑ The Supreme Court enunciated four tests for a state tax in Complete Auto Transit, Inc. v. Brady. Under that case, the out of state taxpayer must have a substantial connection (nexus) with the state, the tax must not discriminate against interstate commerce, the tax must be fairly apportioned, and there must be a fair relationship of the tax to services provided.

- ↑ Bittker & Eustice section 1.01, Pratt & Hulsrud 2005 p.1-4, Willis|Hoffman p. 1-2 and 1-3.

- ↑ For a more complete history, see Seidman's Legislative History of Income Tax Laws, 1938, reprinted 2003 as ISBN 1-58477-336-7.

- ↑ David Kocieniewski (2 May 2011), "U.S. Business Has High Tax Rates but Pays Less" The New York Times

- ↑ 26 CFR 301.7701-2, 301.7701-3, Bittker & Eustice chapter 2, and Fox chapter 31.

- ↑ 26 USC 61.

- ↑ 26 USC 63.

- ↑ Willis|Hoffman 2009, p. 17-8 and -9.

- ↑ 26 USC 1211(a).

- ↑ For example, charitable contributions of a corporation are limited to 10% of taxable income under 26 USC 170(b)(2). For a comparison of how individuals and corporations are taxed, see Willis|Hoffman 2009 p. 17–36, 37.

- ↑ 26 USC 243 and 26 USC 246, Bittker & Eustice section 5.05.

- ↑ 26 USC 248, Bittker & Eustice section 5.06.

- ↑ See, e.g., New York, supra, which bases taxable income on federal taxable income, with minor modification, but separately taxes 'income from subsidiary capital.'

- ↑ Willis|Hoffman 2009 p. 4–5 et seq, Pratt & Kulsrud p. 5–13 et seq.

- ↑ Form 1120 Instructions for 2015 page 17

- ↑ http://www.taxfoundation.org/taxdata/show/230.html

- ↑ http://www.ksrevenue.org/pdf/taxexpreport.pdf pg. 8

- ↑ Pratt & Kulsrud 2005 p. 15-26 et seq, Willis|Hoffman 2009 chapter 12.

- ↑ 26 USC 901, et seq.

- ↑ For statistics related to federal taxes, see IRS Statistics on Income, available in .pdf and Excel formats for many years. Note that some statistics are based on counts of returns, and some are based on samples. For 2006 for all corporations, the total foreign tax credit for corporations was $78 billion, the general business credit $16 billion, and prior year AMT credit $7 billion, on total pre-credit taxes of $463 billion.

- ↑ Jesse Drucker (October 21, 2010). "Google 2.4% Rate Shows How $60 Billion Lost to Tax Loopholes". Bloomberg L.P. Retrieved March 15, 2013.

- 1 2 http://www.americanprogress.org/issues/2011/03/te_031611.html

- ↑ Levin, Carl (20 September 2012). "PSI Memo on Offshore Profit Shifting and the U.S. Tax Code". United States Senate Subcommittee on Investigations. p. 6. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- ↑ Some limitations apply to all corporations, while some apply only to corporate payments to foreign related parties. See, e.g., 26 USC 163(j), 267, 385. Without such limitation, owners could structure financing of the corporation in a manner that would provide for a tax deduction for much of the profits, potentially without changing the tax on shareholders. For example, assume a corporation earns profits of 100 before interest and would normally distribute 50 to shareholder individuals. If the corporation is structured so that deductible interest of 50 is payable to the shareholders, it will cut its tax to half the amount due if it merely paid a dividend. Absent the recently enacted rate differential on dividends, the shareholders' tax would be the same in either case.

- ↑ for [Tax Notes] article circa 1986.

- ↑ 26 USC 163(j) and long-proposed regulations thereunder. See Bittker & Eustice section 4.04[8] for a brief outline.

- ↑ JCX-49-11, Joint Committee on Taxation, September 22, 2011, pp 85. http://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=4363

- ↑ 26 USC 351. Bittker & Eustice chapter 3, Willis|Hoffman 2009 chapter 17, Pratt & Kulsrud 2005 pp.19–30 et seq.

- ↑ 26 USC 351.

- ↑ 26 USC 362.

- ↑ 26 USC 357 and 26 CFR 1.367-1(b) Example.

- ↑ 26 USC 354-358 and 361-362.

- ↑ See 26 USC 368(a)(1)(B) 26 USC 368

- ↑ See generally USC 368(a)(1)(D) 26 USC 368

- ↑ See, e.g., 26 USC 368 defining events qualifying for reorganization treatment, including certain acquisitions. Bittker & Eustice chapter 12. Willis|Hoffman p. 20-14 et seq.

- ↑ Davis, Bruce; Bast, Donald; Sellers, Tracey. "Sales Taxes and Business Reorganizations: A Primer". Transaction Advisors. ISSN 2329-9134.

- ↑ "US Corporate Profits after Taxes". Federal Reserve Board, St. Louis. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ↑ See 26 USC 61(a)(7). See Bittker & Eustice chapter 8, Willis|Hoffman 2009 chapter 19, and Pratt & Kulsrud 2005 chapter 20 for a thorough discussion of non-liquidating distributions, including earnings and profits, and Bittker & eustice chapters 9 and 10 and Pratt & Kulsrud pp. 20–14 et seq for a discussion of redemptions and liquidating distributions.

- ↑ See 26 USC 1(h)(11) for the reduced rate of tax for individuals, and 26 USC 243(a)(1)

- ↑ 26 USC 332

- ↑ 26 USC 302.

- ↑ 26 US 311.

- ↑ 26 USC 301. Dividend is defined at 26 USC 316. Bittker & Eustice section 8.03.

- ↑ 26 USC 312.

- ↑ 26 USC 301(c).

- ↑ Taxation of corporate liquidations.

- ↑ Contrast tax on domestic corporations under 26 USC 11 and 26 USC 63 with tax on foreign corporations under 26 USC 881-885. See Bittker & Eustice sections 15.01 to 15.04, Willis|Hoffman pp. 25–35.

- ↑ See, e.g., 26 USC 882.

- ↑ 26 USC 884. Bittker & Eustice section 15.04[2].

- ↑ 26 USC 1501-1505 and extensive extensive regulations under 1.1502-1 et seq. See Crestol, et al cited below.

- ↑ 26 USC 482 and extensive regulations thereunder.

- ↑ 26 USC 55-59. Also see IRS instructions to Form 4626.

- ↑ 26 USC 531-565. See Bittker & Eustice, chapter 7.

- ↑ 26 USC 11(b).

- ↑ "U.S. Corporation Income Tax Return" (PDF). Internal Revenue Service. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ↑ 26 USC 6012(a)(2). See individual states for requirements.

- ↑ See, e.g., New Jersey's 17+ page Form CBT100 that incorporates limitations on related party interest and royalties, an alternative tax, 3 factor apportionment, depreciation adjustments, special taxes for professional corporations, and other features.

- ↑ See page 38f Instructions for Form 1120-S.

- ↑ 26 USC 6072(b).

- ↑ See, e.g., instructions to IRS Form 7004.

- ↑ 26 USC 6651-6665.

- ↑ See, e.g., 26 USC 6662 for penalties up to 40% of tax related to transfer pricing or valuation adjustments.

- ↑ 26 USC 7201 et seq.