(ε, δ)-definition of limit

In calculus, the (ε, δ)-definition of limit ("epsilon–delta definition of limit") is a formalization of the notion of limit. The concept is due to Augustin-Louis Cauchy, who never gave an () definition of limit in his Cours d'Analyse, but occasionally used arguments in proofs. It was first given as a formal definition by Bernard Bolzano in 1817, and the definitive modern statement was ultimately provided by Karl Weierstrass.[1][2] It makes rigorous the following informal notion: the dependent expression f(x) approaches the value L as the variable x approaches the value c if f(x) can be made as close as desired to L by taking x sufficiently close to c.

History

Isaac Newton was aware, in the context of the derivative concept, that the limit of the ratio of evanescent quantities was not itself a ratio, as when he wrote:

- Those ultimate ratios ... are not actually ratios of ultimate quantities, but limits ... which they can approach so closely that their difference is less than any given quantity...

Occasionally Newton explained limits in terms similar to the epsilon–delta definition.[3] Augustin-Louis Cauchy gave a definition of limit in terms of a more primitive notion he called a variable quantity. He never gave an epsilon–delta definition of limit (Grabiner 1981). Some of Cauchy's proofs contain indications of the epsilon–delta method. Whether or not his foundational approach can be considered a harbinger of Weierstrass's is a subject of scholarly dispute. Grabiner feels that it is, while Schubring (2005) disagrees.[1] Nakane concludes that Cauchy and Weierstrass gave the same name to different notions of limit.[4]

Informal statement

Let f be a function. To say that

means that f(x) can be made as close as desired to L by making the independent variable x close enough, but not equal, to the value c.

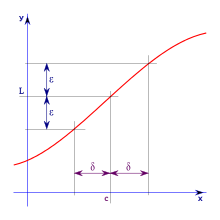

How close is "close enough to c" depends on how close one wants to make f(x) to L. It also of course depends on which function f is and on which number c is. Therefore, let the positive number ε (epsilon) be how close one wishes to make f(x) to L; strictly one wants the distance to be less than ε. Further, if the positive number δ is how close one will make x to c, and if the distance from x to c is less than δ (but not zero), then the distance from f(x) to L will be less than ε. Therefore, δ depends on ε. The limit statement means that no matter how small ε is made, δ can be made small enough.

The letters ε and δ can be understood as "error" and "distance", and in fact Cauchy used ε as an abbreviation for "error" in some of his work.[1] In these terms, the error (ε) in the measurement of the value at the limit can be made as small as desired by reducing the distance (δ) to the limit point.

This definition also works for functions with more than one argument. For such functions, δ can be understood as the radius of a circle or a sphere or some higher-dimensional analogy centered at the point where the existence of a limit is being proven, in the domain of the function and, for which, every point inside maps to a function value less than ε away from the value of the function at the limit point.

Precise statement

The definition of the limit of a function is as follows:[5]

Let be a function defined on a subset , let be a limit point of , and let be a real number. Then

- the function has a limit at

is defined to mean

- for every , there exists a such that for all in that satisfy , the inequality holds.

Symbolically:

Worked example

Let us prove the statement that

This is easily shown through graphical understandings of the limit, and as such serves as a strong basis for introduction to proof. According to the formal definition above, a limit statement is correct if and only if confining to units of will inevitably confine to units of . In this specific case, this means that the statement is true if and only if confining to units of 5 will inevitably confine

to units of 12. The overall key to showing this implication is to demonstrate how and must be related to each other such that the implication holds. Mathematically, we want to show that

Simplifying, factoring, and dividing 3 on the right hand side of the implication yields

which immediately gives the required result if we choose

Thus the proof is completed. The key to the proof lies in the ability of one to choose boundaries in , and then conclude corresponding boundaries in , which in this case were related by a factor of 3, which is entirely due to the slope of 3 in the line

Continuity

A function f is said to be continuous at c if it is both defined at c and its value at c equals the limit of f as x approaches c:

If the condition 0 < |x − c| is left out of the definition of limit, then requiring f(x) to have a limit at c would be the same as requiring f(x) to be continuous at c.

f is said to be continuous on an interval I if it is continuous at every point c of I.

Comparison with infinitesimal definition

Keisler proved that a hyperreal definition of limit reduces the quantifier complexity by two quantifiers.[6] Namely, converges to a limit L as tends to a if and only if for every infinitesimal e, the value is infinitely close to L; see microcontinuity for a related definition of continuity, essentially due to Cauchy. Infinitesimal calculus textbooks based on Robinson's approach provide definitions of continuity, derivative, and integral at standard points in terms of infinitesimals. Once notions such as continuity have been thoroughly explained via the approach using microcontinuity, the epsilon–delta approach is presented as well. Karel Hrbáček argues that the definitions of continuity, derivative, and integration in Robinson-style non-standard analysis must be grounded in the ε–δ method in order to cover also non-standard values of the input.[7] Błaszczyk et al. argue that microcontinuity is useful in developing a transparent definition of uniform continuity, and characterize the criticism by Hrbáček as a "dubious lament".[8] Hrbáček proposes an alternative non-standard analysis, which (unlike Robinson's) has many "levels" of infinitesimals, so that limits at one level can be defined in terms of infinitesimals at the next level.[9]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Grabiner, Judith V. (March 1983), "Who Gave You the Epsilon? Cauchy and the Origins of Rigorous Calculus" (PDF), The American Mathematical Monthly, Mathematical Association of America, 90 (3): 185–194, doi:10.2307/2975545, JSTOR 2975545, archived (PDF) from the original on 2009-05-03, retrieved 2009-05-01

- ↑ Cauchy, A.-L. (1823), "Septième Leçon - Valeurs de quelques expressions qui se présentent sous les formes indéterminées Relation qui existe entre le rapport aux différences finies et la fonction dérivée", Résumé des leçons données à l’école royale polytechnique sur le calcul infinitésimal, Paris, archived from the original on 2009-05-03, retrieved 2009-05-01, p. 44.. Accessed 2009-05-01.

- ↑ Pourciau, B. (2001), "Newton and the Notion of Limit", Historia Mathematica, 28 (1), doi:10.1006/hmat.2000.2301

- ↑ Nakane, Michiyo. Did Weierstrass's differential calculus have a limit-avoiding character? His definition of a limit in ε−δ style. BSHM Bull. 29 (2014), no. 1, 51–59.

- ↑ Rudin, Walter (1976). Principles of Mathematical Analysis. McGraw-Hill Science/Engineering/Math. p. 83. ISBN 978-0070542358.

- ↑ Keisler, H. Jerome (2008), "Quantifiers in limits" (PDF), Andrzej Mostowski and foundational studies, IOS, Amsterdam, pp. 151–170

- ↑ Hrbacek, K. (2007), "Stratified Analysis?", in Van Den Berg, I.; Neves, V., The Strength of Nonstandard Analysis, Springer

- ↑ Błaszczyk, Piotr; Katz, Mikhail; Sherry, David (2012), "Ten misconceptions from the history of analysis and their debunking", Foundations of Science, arXiv:1202.4153

, doi:10.1007/s10699-012-9285-8

, doi:10.1007/s10699-012-9285-8 - ↑ Hrbacek, K. (2009). "Relative set theory: Internal view". Journal of Logic and Analysis. 1.

Further reading

- Grabiner, Judith V. (1982). The Origins of Cauchy's Rigorous Calculus. Courier Corporation. ISBN 978-0-486-14374-3.

- Schubring, Gert (2005). Conflicts Between Generalization, Rigor, and Intuition: Number Concepts Underlying the Development of Analysis in 17th–19th Century France and Germany (illustrated ed.). Springer. ISBN 0-387-22836-5.