Erik Carlsson

.jpg)

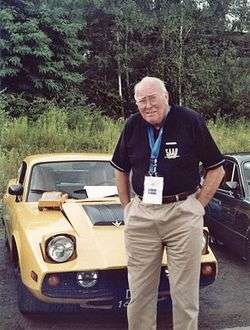

Erik Hilding Carlsson (5 March 1929 – 27 May 2015) was a Swedish rally driver for Saab. He was nicknamed "Carlsson på taket" ("Carlsson on the roof") as well as Mr. Saab (due to of his public relations work for the company).

Early life

Carlsson was born in Trollhättan. Erik Carlsson married Pat Moss on July 9, 1963[1] in London. Pat was also a famous rally driver and younger sister of Stirling Moss. On December 1, 1969 they had a daughter, Susie Carlsson, who was later to become successful in show jumping.

Saab car history and folklore

In John Gardner's James Bond novel Icebreaker, Bond receives several weeks of driving training from Erik Carlsson, as preparation for an arctic assignment. Carlsson also outfits and delivers Bond's "Silver Beast", a Saab 900 Turbo, in Licence Renewed.

Because the early Saabs in which he competed were seriously underpowered and with the tuned two-strokers it was necessary to keep the revs up, he had to maintain a high speed while cornering and practiced left-foot braking to perfection.

Rally career

In 1965 Pat Moss and Erik Carlsson wrote a book: The Art and Technique of Driving (published by Heinemann, London, selling for 25 shillings). This book was translated into Dutch, German, Japanese and Spanish.

The expression "Carlsson on the roof" originated from the children's story Karlsson på taket by Astrid Lindgren, in which a Karlsson character lived on the roof of an apartment building. The name was given to Carlsson as a result of his habit of occasionally rolling a rally car onto its roof. In the Safari Rally, he even rolled the car intentionally, to escape from a mud pool. When journalists later doubted his story, he proved it by rolling the car again. The Ford factory team then tried the same stunt with their Ford Cortina, causing more damage to the car than had occurred during the entire rally.

Carlsson has done a number of unusual things during his rally career. During one rally in the United Kingdom, he needed a spare part and happened to find a brand new Saab 96 on a parking lot. He and the mechanic quickly started disassembling the car when the rather upset owner discovered them. The co-driver managed to defuse the situation by explaining that Carlsson was a factory driver for Saab and the owner would be given a new car. In the end Carlsson could keep driving and they remained friends and still exchange Christmas cards. At the time, rally regulations often stipulated penalties for damage to the car at the finish. Towards the end of the rally, Carlsson's car had acquired dents to both the front fender and one door, so to avoid the penalty points they stopped and switched the door and bumper with the support car. Then it looked a bit suspicious to have a clean door and fender while the rest of the car was covered in mud and dust. As they had no water they used the spare gasoline to wash off the car. Reporters covering the event were impressed that they had had the time to wash the car before arriving at the rally finish. After the finishing festivities, Carlsson looked out the window from his hotel room and saw the support car parked outside: clean, but with a dirty door and fender, still with the starting number visible in the dust.

Carlsson started the 1959 Rally of Portugal leading the European championship. His closest competitor was Paul Coltelloni, a works Citroën team driver, but to prevent Carlsson from winning, Citroën had bought Coltelloni an Alfa Romeo. As the event passed through Spain, the blue Saab Carlsson was sharing with British Rally Champion John Sprinzel began suffering from a grabbing front brake. Cresting the brow of a hill in the gathering dusk at over 70 mph (110 km/h), the crew spotted a closed railway level crossing only yards in front of them. Heavy braking caused the car to spin and roll over into the barrier, where they narrowly avoided being hit by the passing train. Despite this incident, and the subsequent electrical problems it caused, they finished third and it was enough to finish fourth for Carlsson to win the championship. However, shortly before the prize ceremony, they were told they would be given a 25-point penalty for their car having white competition numbers on a black background, instead of the other way around. Still, 25 penalty points only pushed them down to 4th place, so the European championship would be safe. It was only at the prize ceremony itself that they discovered that they had been given an additional 25-point penalty, putting them in eighth position. When they asked why, they were told they had been given 25 penalty points per door.[2]

In the 1966 Coupe des Alpes Carlsson drove an almost-competitive car, a Saab Sonett II. The two-stroke engine had been bored to 940 cc compared to the 841 of the standard model and it gave at most 93 bhp (69 kW; 94 PS). The final drive was geared down so the top speed was only 140 km/h (87 mph), but 100 km/h (62 mph) could be reached from standstill in eight seconds. The car was capable of holding station with the Porsche 904. But they ran into problems with the spark plugs. Frequent spark plug changes were not unusual for tuned two-stroke engines, but it used up spark plugs at an unusual rate and soon they had run out of spare spark plugs and had to give up. Sabotage was suspected and the gasoline was sent to Saab for analysis, where they found that it had been contaminated with a foreign substance.

In the 1961 German Rally the DKW team started a rumour that he was using an illicit four-speed gearbox in his Saab 96 (the standard car only had three gears). They disassambled the gearbox, but found no fourth gear. It turned out that Carlsson had fooled them by dipping the clutch in third gear to make it sound like a four speed.[3] In 2010, Carlsson was among the first four inductees into the Rally Hall of Fame, along with Rauno Aaltonen, Paddy Hopkirk and Timo Mäkinen.[4] Carlsson died on 27 May 2015.[5]

Victories

- 1955 1st in the Rikspokalen in a Saab 92

- 1957 1st in the 1000 Lakes Rally in a Saab 93

- 1959 1st in the Swedish Rally in a Saab 93

- 1959 1st in the Rallye Deutschland in a Saab 93

- 1960, 1961, 1962 1st in the RAC Rally in a Saab 96

- 1960 2nd in the Akropolis Rally in a Saab 96

- 1961 4th in the Monte Carlo Rally in a Saab 95

- 1961 1st in the Akropolis Rally in a Saab 96

- 1962, 1963, 1st in the Monte Carlo Rally in a Saab 96.

- 1962, 7th in East African Safari Rally in a Saab 96

- 1963 2nd in the Liège-Sofia-Liège Rally in a Saab 96

- 1964 1st in the San Remo Rally (Rally dei Fiori) in a Saab 96 Sport

- 1964 2nd in the Liège-Sofia-Liège Rally in a Saab 96

- 1964 2nd in the East African Safari Rally in a Saab 96

- 1965 2nd in the BP Australian Rally in a Saab 96 Sport

- 1965 2nd in the Akropolis Rally in a Saab 96 Sport

- 1967 1st in the Czech Rally in a Saab 96 V4

- 1969, 3rd in Baja 1000 in a Saab 96 V4

- 1970, 5th in Baja 1000 in a Saab 96 V4

Death

Carlsson died on 27 May 2015 after battling a short illness.

References

- ↑ Mr Saab, The Tale of Erik Carlsson "on the roof", page 9. ISBN 91-7125-060-3

- ↑ Spritely Years (Patrick Stephens, 1994) by John Sprinzel and Tom Coulthard.

- ↑ Octane: Carlsson’s half-century

- ↑ "New Inductees to Rally Hall of Fame". Neste Oil Rally Finland. 9 February 2011. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ↑ Rabe, Mattias (27 May 2015). "Erik Carlsson "Carlsson på taket" är död". Teknikens värld (in Swedish). Bonnier Tidskrifter. Retrieved 27 May 2015.

External links

Media related to Erik Carlsson at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Erik Carlsson at Wikimedia Commons