Indian yellow

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

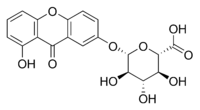

| IUPAC name

(2S,3S,4S,5R,6S)-3,4,5-Trihydroxy-6-(8-hydroxy-9-oxo-9H-xanthen-2-yloxy)-tetrahydro-pyran-2-carboxylic acid | |

| Identifiers | |

| 525-14-4 | |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| ChemSpider | 21106448 |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C19H16O10 | |

| Molar mass | 404.33 g·mol−1 |

| Density | 1.737 g/ml |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| | |

| Infobox references | |

| Indian Yellow | |

|---|---|

| Hex triplet | #E3A857 |

| sRGBB (r, g, b) | (227, 168, 87) |

| HSV (h, s, v) | (35°, 62%, 89%) |

| Source | The Mother of All HTML Colo(u)r Charts |

|

B: Normalized to [0–255] (byte) | |

Indian yellow, also called euxanthin or euxanthine, is a xanthonoid. It is transparent yellow pigment used in oil painting and watercolors. Chemically it is a magnesium euxanthate, a magnesium salt of euxanthic acid. Indian yellow is a clear, deep and luminescent yellow pigment with a color deeper than gamboge but less pure than cadmium yellow.

Indian yellow is a glycoside, a conjugate of the aglycone euxanthone with glucuronic acid, making the chromophore euxanthone much more water-soluble.

Due to its fluorescence, Indian yellow is especially vivid and bright in sunlight. It was likely first used by Dutch artists. Before the end of the 18th century it was commonly used by artists across Europe. The origin of Indian yellow was unknown until 1883; in 2004, British journalist and writer Victoria Finlay questioned this origin.

History

Indian yellow pigment is claimed to have been originally manufactured in rural India from the urine of cattle fed only on mango leaves and water. The urine would be collected and dried, producing foul-smelling hard dirty yellow balls of the raw pigment, called "purree".[1] The process was allegedly declared inhumane and outlawed in 1908,[2] as the cows were extremely undernourished, partly because the leaves contain the toxin urushiol which is also found in poison ivy. The pigment has not been available commercially since 1921. [3]

Nicholas Eastaugh reports in his Pigment Compendium that a description of the above process was given by a Mr. T.N. Mukharji of Calcutta, who claimed to have studied the process in Monghyr, north-east Bihar, India. He describes how urine was collected in small pots, cooled, then concentrated over a fire. The liquid was then filtered through cloth and the sediment collected in balls, then dried over a fire and in the sun. Importers in Europe would then wash and purify the balls, separating greenish and yellow phases.

In "The Art of Painting in Oil and Fresco," [4] by MJFL Mérimée, originally published in 1839, Mérimée states a possible source for the yellow lake:

...the coloring matter is extracted from a tree or large shrub, called memecylon tinctorium, the leaves of which are employed by the natives in their yellow dyes. From a smell like cow's urine, which exhales from this colour, it is probable that this material is employed in extracting the tint of the memecylon.

In 1844, chemist John Stenhouse examined the origin of Indian yellow in an article published in the November 1844 edition of the Philosophical Magazine. At that time the balls of purree imported from India and China came in balls of around 3 ounces (85 g) - 4 ounces (110 g) which when broken open showed a deep orange color. Viewed under a microscope, it showed small needle-shaped crystals, while its smell was said to resemble that of castor oil. Stenhouse reported that Indian yellow was commonly thought to either be composed of gallstones from different animals, including camels, elephants, and buffalos, or deposited from the urine of some of these animals. He carried out a chemical analysis and concluded that he believed it was in fact of vegetable origin, and was "the juice of some tree or plant, which, after it has been expressed, has been saturated with magnesia and boiled down to its present consistence."[5]

In her 2004 book Color: A Natural History of the Palette,[6] Victoria Finlay examined whether Indian yellow was really made from cow urine. The only printed source mentioning this practice is a single letter written by Mr. T.N. Mukharji, who claimed to have seen the color being made. Aside from this letter, there appear to be no written sources from the time period mentioning the production of Indian yellow. Finlay searched for legal records concerning the supposed banning of Indian yellow production in both the India Library in London and the National Library in Calcutta, and found none. She visited the town in India mentioned in Mukharji's letter as the only source of the color, but found no trace of evidence that the color had ever been produced there. None of the locals she spoke with had ever heard of the practice. It is possible that Indian yellow came from another source, and that the cow urine story was fabricated by Mukharji, but came to be accepted by later authors. As such, the viability of producing Indian yellow from the urine of mango-leaf-fed cows is unknown.

Modern alternatives

The replacement for the original pigment (which was not entirely resistant to light), synthetic Indian yellow hue, is a mixture of nickel azo, hansa yellow, and quinacridone burnt orange. It is also known as azo yellow light and deep, or nickel azo yellow.

Notes

- ↑ History of Indian Yellow

- ↑ Baer, N. S. et al. 'Indian Yellow', in Feller, Robert L (ed.) Artists' Pigments, Oxford 1986 ISBN 0-89468-086-2

- ↑ Artists' pigments : a handbook of their history. V.1. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.32106007869669?urlappend=%3Bseq=24

- ↑ Merimee, M.J.F.L. (8/5/2009). The Art of Painting in Oil and Fresco. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4371-4116-0. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Stenhouse

- ↑ Finlay, Victoria (2003). Color: A Natural History of the Palette. Random House. ISBN 0-8129-7142-6.

References

- Eastaugh, Nicholas (2004). Pigment Compendium: A Dictionary of Historical Pigments. Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 0-7506-5749-9.

- Stenhouse, John (November 1844). "Examination of a yellow substance from India called Purree...". The London, Edinburgh and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science: 321–325.

- Merimee, M.J.F.L. (8/5/2009). "The Art of Painting in Oil and Fresco". Kessinger Publishing: 109. ISBN 978-1-4371-4116-0. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - N.S. Baer, A. Joel, L. Feller and N. Indictor, Indian Yellow, in Artists’ Pigments. A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics, Vol. 1: Feller, R.L. (Ed.) Oxford University Press 1986, pp. 17-36.

- Indian Yellow, ColourLex

External links

-

"Indian Yellow". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

"Indian Yellow". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.