Extreme cinema

Extreme cinema is a genre of film distinguished by its use of excessive violence, torture, and sex of extreme nature. The rising popularity of Asian films in the 21st century has contributed to the growth of extreme cinema, although extreme cinema is still considered to be a cult-based genre. Being a relatively new genre it is, extreme cinema is controversial and widely unaccepted by the mainstream media.[1]

Extreme cinema is a growing genre, highly influenced by European and Asian film production in the recent years. Extreme cinema films target a specific and small audience group.

History

First major film to be considered an extreme cinema was Salo: Or 120 Days of Sodom, an Italian-French movie directed by Pier Paolo Pasolini. The film was originally rejected by BBFC. It remains banned from several countries. Despite its controversy, Salo: Or 120 Days of Sodom remains to be the pioneer of extreme cinema.

The production of extreme cinema film was not popular until the late 1990s. It gained more popularity in Asia and Europe, making its way into the mainstream Hollywood production.

The genre of extreme cinema itself is relatively short; the term was widely used until the early 2000s. The name ‘extreme cinema’ originated from a “line of Asian films that share a combination of sensational features, such as extreme violence, horror and shocking plots”,[2] distributed by the Tartan Film, a British/American film distribution company. These Asian films were labeled as “Asian Extreme” and sold, turning a line of obscure film into a new genre.

Influence of Asian Cinema

Hollywood remakes of J-horror movies like Ju-on and Ringu have drawn attention and popularity in Asian cinema. This transition of J-horror movies into popular Hollywood films has contributed to the production of extreme cinema in the US.

Controversy

Extreme cinema is highly criticized and debated by film critics and the general public. There have been debates over the hypersexualization that makes these films a threat to the ‘mainstream’ community standards.[3]

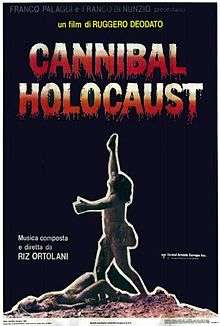

Many of the infamous works that are considered to be extreme films are banned in several countries. A notable example is an Italian horror film Cannibal Holocaust, which was banned in Italy, Australia, and several other countries due to its portrayal of graphic brutality, sexual assault, and violence towards animals. Although some countries have lifted the ban, this film is still banned in over 50 countries.

There has also been criticism over the increasing use of violence in modern-day films. Ever since the emergence of slasher-gore films in the 70’s, the rising popularity of extreme cinema has contributed to the casual violence in popular media.[4] Some criticizes the easy exposure and unintended targeting of adolescence by extreme cinema films.[5]

Cult Films

Cult Films are movies that have gained a dedicated and passionate fan base with an elaborate subculture that engage in audience participation. Extreme cinema is considered to be a cult film. The introduction of Japanese and Asian horror films contributed to the rise of extreme cinema as part of cult films.

Relation with Art films

Art film (also known as a Specialty film) is a serious, independent film aimed at niche market rather than the mass-market media. These films are primarily for “aesthetic reasons rather than commercial profit.” Extreme films are often considered to be an art film.

Classification and Guidelines

BBFC (British Board of Film Classification) classifies extreme cinema films into a ‘R18’ rating, which is defined as “special and legally restricted classification primarily for explicit works of consenting sex or strong fetish material involving adults.”[3]

Many of the infamous works that are considered to be extreme films are banned in several countries. A notable example is an Italian horror film Cannibal Holocaust, which was banned in Italy, Australia, and several other countries due to its portrayal of graphic brutality, sexual assault, and violence towards animals. Some films are given the rating of NC-17 in the U.S, while some are banned from being shown in theaters.

Extreme cinema being classified as a genre itself stirs a controversy.

Psychology

Some of the controversies surrounding extreme cinema has been its effect when exposed to the general public without the proper censorship. Some studies have suggested the correlation between exposure to extreme sex and violence from media and violent behavior and aggression in children.[6]

Notable Films

Some of the more infamous films are films like Cannibal Holocaust and A Serbian Film, which were both banned by countries all over the world due to their “offensive and disturbing content”. Cannibal Holocaust stirred even more controversy with an accusation of it being a snuff film, which resulted in the actors and the director testifying in court. Other works like The Guinea Pig Series have also been accused of being snuff films and were investigated by the FBI.

The Vengeance Trilogy directed by Chan-Wook Park have been highly recognized and rated by critics and the general audience.

Other notable films include Audition, Martyr, Ichi the Killer, Salo: Or the 120 Days of Sodom, and the Guinea Pig series.

References

- ↑ Dirks, Tim. “100 Most Controversial Films of All Time.” 100 Most Controversial Films of All Time. Filmsite, n.d. Web. 9 Feb. 2016.

- ↑ Lee, Eunah. “Trauma, excess, and the aesthetics of the affect: the extreme cinemas of Chan-Wook Park.” Post Script 2014:33. Literature Resource Center. Web. 7 Feb. 2016.

- 1 2 Pett, E. “A New Media Landscape? The BBFC, Extreme Cinema As Cult, And Technological Change.” New Review of Film and Television Studies 13.1 (2015): 83-99. Scopus. Web. 9 Feb. 2016

- ↑ Sapolsky, Barry S., Fred Moliter, and Sarah Luque. “Sex and Violence in Slasher Films: Re-examining the Assumptions.” J&MC Quarterly 80.1 (2003): 28-38. SAGE Journals. Web. 9 Feb. 2016.

- ↑ Sargent, James D., Todd F. Hetherton, M. Bridget Ahrens, Madeline A. Dalton, Jennifer J. Tickle, and Michael L. Beach. “Adolescent Exposure to Extremely Violent Movies.” Journal of Adolescent Health 31.6 (2002): 449-454. JAMES MADISON UNIV’s Catalog. Web.

- ↑ Fyfe, Kristen. “More Violence, More Sex, More Troubled Kids.” Media Research Center. MRC Culture, 11 Jan. 2007. Web. 9 Feb. 2016

Sources

1. Lee, Eunah. “Trauma, excess, and the aesthetics of the affect: the extreme cinemas of Chan-Wook Park.” Post Script 2014:33. Literature Resource Center. Web. 7 Feb. 2016.

2. Review of Film And Television Studies 13.1 (2015): 83-99. Scopus. Web. 7 Feb. 2016

3. Totaro, Donato. “Sex and Violence: Journey into Extreme Cinema.” Offscreen7.11 (2003): n. pag. Web.

4. King, Mike. The American Cinema of Excess: Extremes Of The National Mind On Film. n.p.: Jefferson, N.C : McFarland, c2009., 2009. JAMES MADISON UNIV’s Catalog. Web. 10. Feb. 2016

5. Malamuth, Neil. “Media’s New Mood: Sexual Violence.” Media’s New Mood: Sexual Violence. N.p., n.d. Web. 8 Feb. 2016.

6. Fyfe, Kristen. “More Violence, More Sex, More Troubled Kids.” Media Research Center. MRC Culture, 11 Jan. 2007. Web. 9 Feb. 2016

7. Pett, E. “A New Media Landscape? The BBFC, Extreme Cinema As Cult, And Technological Change.” New Review of Film and Television Studies 13.1 (2015): 83-99. Scopus. Web. 9 Feb. 2016

8. Dirks, Tim. “100 Most Controversial Films of All Time.” 100 Most Controversial Films of All Time. Filmsite, n.d. Web. 9 Feb. 2016.

9. Sapolsky, Barry S., Fred Moliter, and Sarah Luque. “Sex and Violence in Slasher Films: Re-examining the Assumptions.” J&MC Quarterly 80.1 (2003): 28-38. SAGE Journals. Web. 9 Feb. 2016.

10. Sargent, James D., Todd F. Hetherton, M. Bridget Ahrens, Madeline A. Dalton, Jennifer J. Tickle, and Michael L. Beach. “Adolescent Exposure to Extremely Violent Movies.” Journal of Adolescent Health 31.6 (2002): 449-454. JAMES MADISON UNIV’s Catalog. Web.