Facial feedback hypothesis

The facial feedback hypothesis states that facial movement can influence emotional experience. For example, an individual who is forced to smile during a social event will actually come to find the event more of an enjoyable experience.

Background

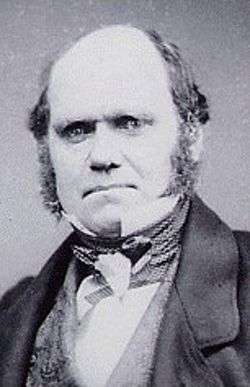

Charles Darwin was among the first to suggest that physiological changes caused by an emotion had a direct impact on, rather than being just the consequence of that emotion. He wrote:

The free expression by outward signs of an emotion intensifies it. On the other hand, the repression, as far as this is possible, of all outward signs softens our emotions... Even the simulation of an emotion tends to arouse it in our minds.[1]:366

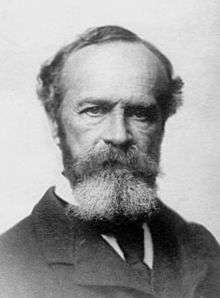

Following on this idea, William James proposed that, contrary to common belief, awareness of bodily changes activated by a stimulus "is the emotion".[2]:449 If no bodily changes are felt, there is only an intellectual thought, devoid of emotional warmth. In The Principles of Psychology, James wrote: "Refuse to express a passion, and it dies".[2]:463

This proved difficult to test, and little evidence was available, apart from some animal research and studies of people with severely impaired emotional functioning. The facial feedback hypothesis, "that skeletal muscle feedback from facial expressions plays a causal role in regulating emotional experience and behaviour",[3] developed almost a century after Darwin.

Development of the theory

While James included the influence of all bodily changes on the creation of an emotion, "including among them visceral, muscular, and cutaneous effects",[4]:252 modern research mainly focuses on the effects of facial muscular activity. One of the first to do so, Silvan Tomkins wrote in 1962 that "the face expresses affect, both to others and the self, via feedback, which is more rapid and more complex than any stimulation of which the slower moving visceral organs are capable".[4]:255

Two versions of the facial feedback hypothesis appeared, although "these distinctions have not always been consistent".[5]

- The weak version, introduced by Darwin, sees the feedback intensify or reduce an emotion already present. Thomas McCanne and Judith Anderson (1987)[6] instructed participants to suppress or increase the zygomatic or corrugator muscle while imagining pleasant or unpleasant scenes. Subsequent alteration of the emotional response was shown to have occurred.

- The strong version implies that facial feedback by itself can create the whole emotion.

According to Jeffrey Browndyke,[7] "the strongest evidence for the facial feedback hypothesis to date comes from research by Lanzetta et al. (1976)" (but see "Studies using Botox" below for more recent and powerful evidence). Participants had lower skin conductance and subjective ratings of pain when hiding the painfulness of the shocks they endured, compared with those who expressed intense pain.

However, in all research, difficulty remained in how to measure an effect without alerting the participant to the nature of the study and how to ensure that the connection between facial activity and corresponding emotion is not implicit in the procedure.

Methodological issues

Originally, the facial feedback hypothesis studied the enhancing or suppressing effect of facial efference on emotion in the context of spontaneous, "real" emotions, using stimuli. This resulted in "the inability of research using spontaneous efference to separate correlation from causality".[4]:264 Laird (1974)[8] used a cover story (measuring muscular facial activity with electrodes) to induce particular facial muscles contraction in his participants without mentioning any emotional state. However, the higher funniness ratings of the cartoons obtained by those participants "tricked" into smiling may have been caused by their recognising the muscular contraction and its corresponding emotion: the "self-perception mechanism", which Laird (1974) thought was at the root of the facial feedback phenomenon. Perceiving physiological changes, people "fill the blank" by feeling the corresponding emotion. In the original studies, Laird had to exclude 16% (Study 1) and 19% (Study 2) of the participants as they had become aware of the physical and emotional connection during the study.

Another difficulty is whether the process of manipulation of the facial muscles did not cause so much exertion and fatigue that those, partially or wholly, caused the physiological changes and subsequently the emotion. Finally, the presence of physiological change may have been induced or modified by cognitive process.

Experimental confirmation

In an attempt to provide a clear assessment of the theory that a purely physical facial change, involving only certain facial muscles, can result in an emotion, Strack, Martin, & Stepper (1988)[9] devised a cover story that would ensure the participants adopt the desired facial posing without being able to perceive either the corresponding emotion or the researchers' real motive. Told they were taking part in a study to determine the difficulty for people without the use of their hands or arms to accomplish certain tasks, participants held a pen in their mouth in one of three ways. The Lip position would contract the orbicularis oris muscle, resulting in a frown. The Teeth position would cause the zygomaticus major or the risorius muscle, resulting in a smile. The control group would hold the pen in their nondominant hand. All had to fill a questionnaire in that position and rate the difficulty involved. The last task, which was the real objective of the test, was the subjective rating of the funniness of a cartoon. The test differed from previous methods in that there were no emotional states to emulate, dissimulate or exaggerate.

As predicted, participants in the Teeth condition reported significantly higher amusement ratings than those in the Lips condition. The cover story and the procedure were found to be very successful at initiating the required contraction of the muscles without arising suspicion, 'cognitive interpretation of the facial action,[9] and avoiding significant demand and order effects. It has been suggested that more effort may be involved in holding a pen with the lips compared with the teeth.[5]

To avoid the possible effort problem, Zajonc, Murphy and Inglehart (1989) had subjects repeat different vowels, provoking smiles with "ah" sounds and frowns with "ooh" sounds for example, and again found a measurable effect of facial feedback.[5] Ritual chanting of smile vowels has been found to be more pleasant than chanting of frown vowels, which may explain their comparative prevalence in religious mantra traditions.[10]

These studies have resolved many of the methodological issues associated with the facial feedback hypothesis. Darwin's theory can be demonstrated, and the moderate, yet significant effect of this theory of emotions opens the door to new research on the "multiple and nonmutually exclusive plausible mechanisms"[11] of the effects of facial activity on emotions.

Doubts about the robustness of these findings was voiced in 2016 when a replication series of the original 1988 experiment coordinated by Eric-Jan Wagenmakers and conducted in 17 labs did not find any support for the hypothesis.[12]

Studies using botulinum toxin (botox)

Because facial expressions involve both motor (efferent) and sensory (afferent) mechanisms, it is possible that effects attributed to facial feedback are due solely to feedback mechanisms, or feed-forward mechanisms, or some combination of both. Recently, strong experimental support for a facial feedback mechanism is provided through the use of botulinum toxin (commonly known as Botox) to temporarily paralyze facial muscles. Botox selectively blocks muscle feedback by blocking presynaptic acetylcholine receptors at the neuromuscular junction. Thus, while motor efference commands to the facial muscles remain intact, sensory afference from extrafusal muscle fibers, and possibly intrafusal muscle fibers, is diminished.

Several studies have examined the correlation of botox injections and emotion[13][14] and these suggest that the toxin could be used as a treatment for depression. Further studies have used experimental control to test the hypothesis that botox affects aspects of emotional processing. It has been suggested that the treatment of nasal muscles would reduce the ability of the person to form a disgust response which could offer a reduction of symptoms associated with obsessive compulsive disorder.[15]

In a functional neuroimaging study, Andreas Hennenlotter and colleagues[16] asked participants to perform a facial expression imitation task in an fMRI scanner before and two weeks after receiving botox injections in the corrugator supercilii muscle used in frowning. During imitation of angry facial expressions, botox decreased activation of brain regions implicated in emotional processing and emotional experience (namely, the amygdala and the brainstem), relative to activations before botox injection. These findings show that facial feedback modulates neural processing of emotional content, and that botox changes how the human brain responds to emotional situations.

In a study of cognitive processing of emotional content, David Havas and colleagues[17] asked participants to read emotional (angry, sad, happy) sentences before and two weeks after botox injections in the corrugator supercilii muscle used in frowning. Reading times for angry and sad sentences were longer after botox injection than before injection, while reading times for happy sentences were unchanged. This finding shows that facial muscle paralysis has a selective effect on processing of emotional content. It also demonstrates that cosmetic use of botox affects aspects of human cognition - namely, the understanding of language.

Autism spectrum disorders

A study by Mariëlle Stel, Claudia van den Heuvel, and Raymond C. Smeets[18] has shown that the facial feedback hypothesis does not hold for people with autism spectrum disorders (ASD); that is, "individuals with ASD do not experience feedback from activated facial expressions as controls do".

See also

References

- ↑ Darwin, C. (1872). The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. London:John Murray, 366. Fulltext.

- 1 2 James, W. (1890). The Principles of Psychology. Fulltext.

- ↑ Buck, Ross (1980). "Nonverbal Behavior and the Theory of Emotion: The Facial Feedback Hypothesis". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 38 (5): 813. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.38.5.811.

- 1 2 3 Adelmann, Pamela K.; Zajonc, Robert B. (1989). "Facial efference and the experience of emotion". Annual Review of Psychology. 40 (1): 249–280. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.40.1.249.

- 1 2 3 Zajonc, R. B.; Murphy, Sheila T.; Inglehart, Marita (1989). "Feeling and Facial Efference: Implications of the Vascular Theory of Emotion" (PDF). Psychological Review. 96 (3): 396. doi:10.1037/0033-295x.96.3.395. Retrieved 9 November 2014.

- ↑ McCanne, Thomas R.; Anderson, Judith A. (April 1987). "Emotional Responding Following Experimental Manipulation of Facial Electromyographic Activity". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 52 (4): 759–768. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.52.4.759.

- ↑ Browndyke, J. N. (2002). "Neuropsycholosocial factors in emotion recognition: Facial expressions", p3.

- ↑ Laird, James D. (1974). "Self-attribution of emotion: The effects of expressive behavior on the quality of emotional experience". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 29 (4): 475–486. doi:10.1037/h0036125.

- 1 2 Strack, Fritz; Martin, Leonard L.; Stepper, Sabine (May 1988). "Inhibiting and Facilitating Conditions of the Human Smile: A Nonobtrusive Test of the Facial Feedback Hypothesis". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 54 (5): 768–777. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.5.768. PMID 3379579.

- ↑ Böttger, D. (2010) To say "Krishna" is to smile - emotion psychology and the neurology of mantra singing. In "The Varieties of Ritual Experience" (ed. Jan Weinhold & Geoffrey Samuel) in the series "Ritual Dynamics and the Science of Ritual", Volume II: "Body, performance, agency and experience". Wiesbaden, Germany: Harrassowitz.

- ↑ McIntosh, Daniel N. (1996). "Facial feedback hypotheses: Evidence, implications, and directions". Motivation and Emotion. 20 (2): 121–147. doi:10.1007/BF02253868.

- ↑ https://osf.io/qhpdc/?view_only=fbec7d52a52745e8af75b3fe34dffa94

- ↑ Lewis, Michael B; Bowler, Patrick J (2009-03-01). "Botulinum toxin cosmetic therapy correlates with a more positive mood". Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology. 8 (1): 24–26. doi:10.1111/j.1473-2165.2009.00419.x. ISSN 1473-2165.

- ↑ (PDF) http://www.chevychasecosmeticcenter.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/Botox_Depression_Study_pressreleaseFINAL1.pdf. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "Exploring the positive and negative implications of facial feedback.". Emotion. 12: 852–859. doi:10.1037/a0029275.

- ↑ Hennenlotter, A.; Dresel, C.; Castrop, F.; Ceballos Baumann, A. O.; Wohlschlager, A. M.; Haslinger, B. (June 17, 2008). "The Link between Facial Feedback and Neural Activity within Central Circuitries of Emotion—New Insights from Botulinum Toxin–Induced Denervation of Frown Muscles". Cerebral Cortex. 19 (3): 537–542. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhn104.

- ↑ Havas, D. A.; Glenberg, A. M.; Gutowski, K. A.; Lucarelli, M. J. & Davidson, R. J. (July 2010). "Cosmetic Use of Botulinum Toxin-A Affects Processing of Emotional Language". Psychological Science. 21 (7): 895–900. doi:10.1177/0956797610374742. PMC 3070188

. PMID 20548056.

. PMID 20548056. - ↑ Stel, Mariëlle; van den Heuvel, Claudia; Smeets, Raymond C. (Feb 22, 2008). "Facial Feedback Mechanisms in Autistic Spectrum Disorders". Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 38 (7): 1250–1258. doi:10.1007/s10803-007-0505-y. PMC 2491410

. PMID 18293075.

. PMID 18293075.

- Lanzetta, John T.; Cartwright-Smith, Jeffrey; Kleck, Robert E. (1976). "Effects of Nonverbal Dissimulation on Emotional Experience and Autonomic Arousal". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 33 (3): 354–370. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.33.3.354.

Bibliography

- Andréasson, P.; Dimberg, U. (2008). "Emotional empathy and facial feedback". Journal of Nonverbal Behavior. 32 (4): 215–224. doi:10.1007/s10919-008-0052-z.

External links

- Based on a Psychology Wiki article licensed under Creative Commons as CC-BY-SA.