Fantasy coffin

The fantasy or figurative coffins from Ghana, in Europe also called custom, fantastic, or proverbial coffins (abebuu adekai),[1] are functional coffins made by specialized carpenters in the Greater Accra Region in Ghana. These colourful objects which have developed out of the figurative palanquins are not only coffins, but considered real works of art, were shown for the first time to a wider Western public in the exhibition Les Magiciens de la terre at the Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris in 1989. The seven coffins which were exposed in Paris were done by Kane Kwei (1922–1992) and by his former assistant Paa Joe (b.1947).[2] Since then, these art coffins of Kane Kwei, his grandson Eric Adjetey Anang, Paa Joe, Daniel Mensah (Hello), Kudjoe Affutu and other artists have been displayed in many international art museums and galleries around the world.[3]

Origin and Meaning

The reason that mainly the southern Ghana-based Ga people use such elaborate coffins for their funerals is explained by their religious beliefs regarding the afterlife. They believe that death is not the end and that life continues in the next world in the same way it did on earth. Ancestors are also thought to be much more powerful than the living and able to influence their relatives who are still alive. This is why families do everything they can to ensure that a dead person is sympathetic towards them as early as possible. The social status of the deceased depends primarily on the importance, success and usage of an exclusive coffin during a burial.

Fantasy coffins are only seen on the day of the burial when they are buried with the deceased. They often symbolise the dead people’s professions. Certain shapes, such as a sword or stool coffin, represent regal or priestly insignia with a magical and religious function. Only people with the appropriate status are allowed to be buried in these types of coffins. Various animals, such as lions, cockerels and crabs can represent clan totems. Similarly, only the heads of the families concerned are permitted to be buried in coffins such as these. Many coffin shapes also evoke proverbs, which are interpreted in different ways by the Ga. That is why these coffins are also called proverbial coffins (abebuu adekai) or in the Ga language "okadi adekai".

History

Among the Christians the use of custom coffins is relatively new and began in the Greater Accra Region around 1950. These coffins were formerly used only by the Ga chiefs and priests, but since around 1960 figurative coffins have become an integral part of the local funeral culture.[4] The Christians had taken over the figurative coffins from the traditional Ga who were using figurative palanquins and coffins already since the beginning of the 20th century.[5]

The invention of these figurative coffins is usually attributed to Seth Kane Kwei, though the anthropologist Roberta Bonetti[6] and especially Regula Tschumi question this myth. The idea of making and using custom coffins was inspired by the figurative palanquins in which the Ga chiefs were carried, and in which they were sometimes buried.[7] Ataa Oko (b.1919), of La, according to a few sources, could have started making custom coffins and figurative palanquins around 1945. Along with Kane Kwei from Teshie and Ataa Oko from La, other carpenters may have started this innovative art form the early 1950s.

Making the coffins

Figurative coffins are produced only to order. Every master craftsman employs one or more apprentices, who carry out a large part of the work. This allows the artist to make several coffins simultaneously. The coffins are generally made from the wood of the local wawa tree. In the interests of durability, items produced for museums are constructed from mahogany or some other high-grade hardwood so as to guard against cracking and attacks by insects when transferred from one climate to another. A coffin will take two to six weeks to produce, depending on the complexity of the construction and the carpenters’ level of experience. In urgent cases several carpenters will work on a single item. All woodworking is done using the simplest tools, without the aid of electrical appliances. The painting of the figural coffins can take up to two days to finish.Some models are painted by the head of the workshop, others by local sign writers, some of them are even well known on the western art market for their hand-painted movie posters. Coffin-makers and sign-painters usually decide together which patterns and colours to use for a coffin.[8]

Short artist biographies

Kudjoe Affutu

was born in 1985 in Awutu Bawyiase, Central Region, Ghana. Kudjoe Affutu was trained 2002 until 2006 by Paa Joe in Nungua, Greater Accra Region. Since 2007 he runs his own workshop in Awutu Bawyiase, Central Region.

Kudjoe Affutu has collaborated already with different European artists, among them with Thomas Demand, Sâadane Afif and the artist duo M.S. Bastian/Isabelle L. Kudjoe Affutus coffins were exhibited in the Centre Pompidou Paris, In the Tinguely Museum Basel, in the Nouveau Musée National de Monaco and in the Musée d'ethnographie Neuchâtel.

Eric Adjetey Anang

Born in 1985, Eric Adjetey Anang is the grandson of Seth Kane Kwei. He is running the Kane Kwei Carpentry Workshop with his father Cedi since 2005, after he graduated from Accra Academy. Since 2009, Eric Adjetey Anang has been the subject of several documentary movies produced in the UK, France, Brasil, Japan, Norway and the USA. He has been invited as a resident artist in Russia, USA, Belgium, Denmark and organises residences for foreign artists in Ghana. Among other international events, Eric Adjetey Anang was invited in Italy for the Milan Design Week in 2013, in South Korea for the Gwangju Biennale of Design in 2011.

Paa Joe

Paa Joe was born in 1947 in the region of Akwapim, Ghana. He did his apprenticeship with Kane Kwei in Teshie, but left his master 1974. In 1976 he opened his own workshop in Nungua. In 1989 he was invited at the exhibition "Les Magiciens de la terre" in Paris. Since then his coffins have been shown all over the world. In 2005 they were exhibited in the Jack Shainman Gallery in New York and Jack Bell Gallery London. 2006 he participated in the exhibition "Six Feet Under" at the Kunstmuseum Bern. In 2007, he opened a new workshop in Pobiman near Accra.[9] in May 2013 he was in an Artist residence in UK with his son Jacob making a lion coffin, and 2016 the Artdocs film "Paa Joe and the Lion" made by Benjamin Wigley and Anna Griffin (producer) came out.

Eric Kpakpo

Eric Kpakpo was born in 1979 in Nungua, Ghana. He learned carpentry from 1994 until 2000 at Paa Joe's workshop in Nungua. He remained there as a master carpenter until 2006 when he opened his own coffin studio in La.

Daniel Mensah

Daniel Mensah, also called "Hello", was born in 1968 in Teshie, Ghana. He did his six-year apprenticeship with Paa Joe in Nungua. He then spent eight more years with Paa Joe. Only in 1998 did he open his own studio, "Hello Design Coffin Works", in Teshie. He participated in various art exhibitions and in some European film projects. In 2011, he had an exhibition in the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts.

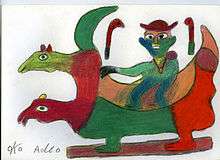

Ataa Oko

Ataa Oko (1919-2012) was born in the coastal town of La, Ghana. From 1936 to 1939 he was trained as a carpenter in Accra. Ataa Oko was, until 2002, not in contact with foreigners, he only made coffins for Ghanaian customers and thus remained unknown in Western art circles. In 2006, his work was for the first time exhibited at the art museum in Bern.[10] Uninfluenced by Western customers, Ataa Oko had developed his own form of artistic language. His work is therefore different from those artists which come out of Kane Kwei's tradition. Therefore, it differs not only in terms of design, materials, but overall appearance.[11] From 2005 to his death in 2012, he became a painter under the supervision of anthropologist Regula Tschumi. 2010/11 he had his first one-man show in a western Art museum, in the Collection de l'Art Brut in Lausanne.

Gallery

Hen coffin by Kudjoe Affutu, 2008.

Hen coffin by Kudjoe Affutu, 2008.- Ataa Oko and Kudjoe Affutu with Okos red rooster coffin 2009.

Centre Pompidou coffin, Kudjoe Affutu, 2010.

Centre Pompidou coffin, Kudjoe Affutu, 2010.

References

- ↑ Alternate Histories of the Abebuu Adekai. Roberta Bonetti, African Arts, Autum 2010.

- ↑ A Deathbed of a Living Man. A Coffin for the Centre Pompidou. Regula Tschumi in Sâadane Afif (ed.), „Anthologie de l’humour noir“, Paris: Editions Centre Pompidou. 2010. P.56.

- ↑ The buried treasures of the Ga. Coffin art in Ghana. Regula Tschumi. Bern: Benteli 2008, p. 230-31.

- ↑ The buried treasures of the Ga. Coffin art in Ghana. Regula Tschumi. Bern: Benteli 2008, p. 52-66.

- ↑ Regula Tschumi: The Figurative Palanquins of the Ga. History and Significance, in: African Arts, Vol. 46, Nr. 4, 2013, S. 60-73.

- ↑ Roberta Bonetti, Alternate Histories of the Abebuu Adekai, African Arts, autumn 2010, p. 14-33: Roberta Bonetti reached the same conclusion as Regula Tschumi considers the well-known stories about the origin of the figure-coffins to have been invented: „[...] We have seen how the same criteria of authenticity that were fundamental in documenting the uniqueness and truthfulness of ancient works have been adopted for recent coffins. The proof is provided by the presumed origin of the work, which has become even more precious and exceptional ever since the death of its „invented“ inventor, Kane Kwei“.

- ↑ The buried treasures of the Ga. Coffin art in Ghana. Regula Tschumi. Bern: Benteli 2008, p. 57, 221-22.

- ↑ The buried treasures of the Ga. Coffin art in Ghana. Regula Tschumi. Bern: Benteli 2008, p. 63-81. Regula Tschumi 2011. Death-bed of a living man. A coffin for the centre Pompidou, in: Eva Huttenlauch (ed): "Another Anthology of Black Humor", MMK Frankfurt: Kunstbuchverlag Nürnberg. p. 46-47.

- ↑ The buried treasures of the Ga. Coffin art in Ghana. Regula Tschumi. Bern: Benteli 2008, p. 242-43.

- ↑ Six Feet Under, 2006. Art Museum Bern, and "Six Feet Under" 2007/2008 in the Deutsches Hygienemuseum, Dresden.

- ↑ Ataa Oko, Ex. Cat., Collection de l'art brut (Hg), Infolio, 2010, p. 15-34.

Bibliography

- Regula Tschumi: Concealed Art. The figurative palanquins and coffins of Ghana. Edition Till Schaap, Bern. ISBN 978-3-03828-099-6.

- Regula Tschumi: The buried treasures of the Ga: Coffin art in Ghana. Edition Till Schaap, Bern, 2014. ISBN 9783038280163. A revised and updated second edition of Benteli 2008.

- Regula Tschumi: The Figurative Palanquins of the Ga. History and Significance, in: African Arts, vol. 46, no. 4, 2013, p. 60-73

- Ataa Oko, Ex. Cat., Collection de l'art brut (ed), Infolio, 2010

- Roberta Bonetti: Alternate Histories of the Abebuu Adekai, in: African Arts, Bd. 43, no. 3, 2010, p. 14-33.

- Vivian Burns: Travel to Heaven: Fantasy Coffins, in: African Arts, vol. 17, no. 2 (1974), p. 24-25

- Jean-Hubert Martin: Kane Kwei, Samuel Kane Kwei, in: André Magnin (ed.): Contemporary Art of Africa. Thames and Hudson, London 1996, p. 76.

- Thierry Secretan: Going into darkness: Fantastic coffins from Africa. London 1995.

- Regula Tschumi: A Report on Paa Joe and the Proverbial Coffins of Teshie and Nungua, Ghana, in: Africa et Mediterraneo, no. 47-8, 2004, pp. 44–7

- Regula Tschumi: Last Respects, First Honoured. Ghanaian Burial Rituals and Figural Coffins, in: Kunstmuseum Bern (ed.): Six Feet Under. Autopsy of Our Relation to the Dead. Kerber, Bielefeld & Leipzig 2006, p. 114-125.

- Regula Tschumi: A Deathbed of a Living Man. A Coffin for the Centre Pompidou, in: Sâadane Afif (ed.), Anthologie de l’humour noir. Edition Centre Pompidou, Paris 2010, p. 56-61.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ghanaian coffin art. |