Ferdinand II of the Two Sicilies

| Ferdinand II | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| King of the Two Sicilies | |||||

| Reign | 8 November 1830 – 22 May 1859 | ||||

| Predecessor | Francis I | ||||

| Successor | Francis II | ||||

| Born |

12 January 1810 Palermo, Sicily | ||||

| Died |

22 May 1859 (aged 49) Caserta, Kingdom of the Two Sicilies | ||||

| Burial | Basilica of Santa Chiara, Naples | ||||

| Spouse |

Maria Cristina of Savoy Maria Theresa of Austria | ||||

| Issue |

Francis II Prince Louis, Count of Trani Prince Albert Maria, Count of Castrogiovanni Prince Alfonso, Count of Caserta Maria Annunciata, Archduchess Charles Louis of Austria Maria Immaculata, Archduchess Karl Salvator of Austria Prince Gaetan, Count of Girgenti Prince Giuseppe, Count of Lucera Maria Pia, Duchess of Parma Prince Vincenzo, Count of Melazzo Prince Pasquale, Count of Bari Maria Luisa Immaculata, Countess of Bardi Prince Januarius, Count of Caltagirone | ||||

| |||||

| House | House of Bourbon-Two Sicilies | ||||

| Father | Francis I of the Two Sicilies | ||||

| Mother | Maria Isabella of Spain | ||||

| Religion | Roman Catholic | ||||

Ferdinand II (Ferdinando Carlo, 12 January 1810 – 22 May 1859) was King of the Two Sicilies from 1830 until his early death in 1859.

Family

Ferdinand was born in Palermo, to King Francis I of the Two Sicilies and his wife (and first cousin) Maria Isabella of Spain.

His paternal grandparents were King Ferdinand I of the Two Sicilies and Queen Maria Carolina of Austria. His maternal grandparents were Charles IV of Spain and Maria Luisa of Parma. Ferdinand I and Charles IV were brothers, both sons of Charles III of Spain and Maria Amalia of Saxony.

Early reign

In his early years he was fairly popular. Progressives credited him with Liberal ideas and, in addition, his free and easy manners endeared him to the so-called lazzaroni, the lower classes of Neapolitan society.

On succeeding to the throne in 1830, he published an edict in which he promised to give his most anxious attention to the impartial administration of justice, to reform the finances, and to use every effort to heal the wounds which had afflicted the Kingdom for so many years. His goal, he said, was to govern his Kingdom in a way that would bring the greatest happiness to the greatest number of his subjects while respecting the rights of his fellow monarchs and those of the Roman Catholic Church.

The early years of his reign were comparatively peaceful: he cut taxes and expenditures, had the first railway in Italy built (between Naples and the royal palace at Portici), his fleet had the first steamship in the Italian Peninsula, and he had telegraphic connections established between Naples and Palermo, Sicily.

However, in 1837 he violently suppressed Sicilian demonstrators demanding a constitution and maintained strict police surveillance in his domains. Progressive intellectuals, who were motivated by visions of a new society founded upon a modern constitution, continued to demand the King to grant a constitution and to liberalize his rule.

Revolutions of 1848

In September 1847, violent riots inspired by Liberals broke out in Reggio Calabria and in Messina and were put down by the military. On 12 January 1848 a rising in Palermo spread throughout the island and served as a spark for the Revolutions of 1848 all over Europe.

After similar revolutionary outbursts in Salerno, south of Naples, and in the Cilento region which were backed by the majority of the intelligentsia of the Kingdom, on 29 January 1848 King Ferdinand was forced to grant a constitution patterned on the French Charter of 1830.

A dispute, however, arose as to the nature of the oath which should be taken by the members of the chamber of deputies. As an agreement could not be reached and the King refused to compromise, riots continued in the streets. Eventually, the King ordered the army to break them and dissolved the national parliament on 13 March 1849. Although the constitution was never formally abrogated, the King returned to reigning as an absolute monarch.

During this period, Ferdinand showed his attachment to Pope Pius IX by granting him asylum at Gaeta. The pope had been temporarily forced to flee from Rome following similar revolutionary disturbances. (See Roman Republic (19th century), Giuseppe Mazzini.)

In the meantime, Sicily proclaimed its independence under the leadership of Ruggeru Sèttimu, who on 13 April 1848 declared the King deposed. In response, the King assembled an army of 20,000 under the command of General Carlo Filangieri and dispatched it to Sicily to subdue the Liberals and restore his authority. A naval flotilla sent to Sicilian waters shelled the city of Messina with "savage barbarity" for eight hours after its defenders had already surrendered, killing many civilians and earning the King the nickname "Rè Bomba" ("King Bomb").

After a campaign lasting close to nine months, Sicily's Liberal regime was completely subdued on 15 May 1849.

Later reign

Between 1848 and 1851, the policies of King Ferdinand caused many to go into exile. Meanwhile, an estimated 2,000 suspected revolutionaries or dissidents were jailed.

After visiting Naples in 1850, Gladstone began to support Neapolitan opponents of the Bourbon rulers: his "support" consisting of a couple of letters that he sent from Naples to the Parliament of London, describing the "awful conditions" of the Kingdom of Southern Italy and claiming that "it is the negation of God erected to a system of government". Gladstone had not actually been to Southern Italy and so some of his accusations were unreliable, but reports of misgovernment in the Two Sicilies were widespread throughout Europe during the 1850s. Gladstone's letters provoked sensitive reactions in the whole of Europe and helped to cause its diplomatic isolation prior to the invasion and annexation of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies by the Kingdom of Piedmont, with the following foundation of modern Italy.

The British government, which had been the ally and protector of the Bourbon dynasty during the Napoleonic Wars, had already additional interests to limit the independence of the kingdom. It had extensive business interests in Sicily and relied on Sicilian sulfur for certain industries.[1] The King had endeavored to limit British influence, which had begun to cause tension. As Ferdinand ignored the advice of the British and the French governments, those powers recalled their ambassadors in 1856.

A soldier attempted to assassinate Ferdinand in 1856, and many believe that the infection he received from the soldier's bayonet led to his ultimate demise. He died on 22 May 1859, shortly after the Second French Empire and the Kingdom of Sardinia had declared war against the Austrian Empire. This would later lead to the invasion of his Kingdom by Giuseppe Garibaldi and Italian unification in 1861.

Marriage and issue

| Name | Birth | Death | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| By Princess Maria Cristina of Savoy (married 21 November 1832 in Cagliari; b. 12 November 1812, d. 21 January 1836) | |||

| Francesco II of the Two Sicilies | 16 January 1836 | 27 December 1894 | succeeded as King of the Two Sicilies married Duchess Maria Sophie in Bavaria; had issue, an only daughter. |

| By Archduchess Maria Theresa of Austria (married 9 January 1837 in Vienna; b. 31 July 1816, d. 8 August 1867) | |||

| Luigi, Count of Trani | 1 August 1838 | 8 June 1886 | married Duchess Mathilde Ludovika in Bavaria; their only daughter, Princess Maria Teresa, married Prince Wilhelm of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen. |

| Alberto, Count of Castrogiovanni | 17 September 1839 | 12 July 1844 | died in childhood. |

| Alfonso, Count of Caserta | 28 March 1841 | 26 May 1934 | married his first cousin Maria Antonia of the Two Sicilies and has issue. The current lines of Bourbon-Sicily descend from him. |

| Maria Annunciata of the Two Sicilies | 24 March 1843 | 4 May 1871 | married Archduke Karl Ludwig of Austria; had issue. |

| Maria Immacolata Clementina of the Two Sicilies | 14 April 1844 | 18 February 1899 | married Archduke Karl Salvator of Austria; had issue. |

| Gaetano, Count of Girgenti | 12 January 1846 | 26 November 1871 | married Infanta Isabel of Spain (eldest daughter of Queen Isabella II of Spain) and was created Infante of Spain; no issue. |

| Giuseppe, Count of Lucera | 4 March 1848 | 28 September 1851 | died in childhood. |

| Maria Pia of the Two Sicilies | 21 August 1849 | 29 September 1882 | married Roberto I, Duke of Parma and Piacenza; had issue. |

| Vincenzo, Count of Melazzo | 26 April 1851 | 13 October 1854 | died in childhood. |

| Pasquale, Count of Bari | 15 September 1852 | 21 December 1904 | married morganatically to Blanche Marconnay; no issue. |

| Maria Luisa of the Two Sicilies | 21 January 1855 | 23 August 1874 | married Prince Henry of Bourbon-Parma, Count of Bardi; no issue. |

| Gennaro, Count of Caltagirone | 28 February 1857 | 13 August 1867 | died in childhood. |

Ancestors

Titles and styles

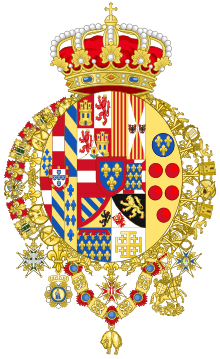

| Royal styles of Ferdinand II of the Two Sicilies | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | His Majesty |

| Spoken style | Your Majesty |

| Alternative style | Sir |

- 12 January 1810 - 12 December 1816 His Royal Highness The Prince Ferdinand of Naples and Sicily

- 12 December 1816 - 4 January 1825 His Royal Highness The Duke of Noto

- 4 January 1825 – 8 November 1830 His Royal Highness The Duke of Calabria

- 8 November 1830 – 22 May 1859 His Majesty The King of the Two Sicilies

Notes

References

- Theroff, Paul. "2sicilies". www.angelfire.com/realm/gotha/ (Paul Theroff’s Royal Genealogy Site).

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ferdinand II of the Two Sicilies. |

- Naples–Portici railway line

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

| Ferdinand II of the Two Sicilies Cadet branch of the House of Bourbon Born: 12 January 1810 Died: 22 May 1859 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Francis I |

King of the Two Sicilies 8 November 1830 – 22 May 1859 |

Succeeded by Francis II |