Fiat BR.20

| BR.20 Cicogna | |

|---|---|

| |

| A Fiat BR.20 on the ground just prior to Italy's declaration of war in 1940. | |

| Role | Medium bomber |

| Manufacturer | Fiat |

| Designer | Celestino Rosatelli |

| First flight | 10 February 1936 |

| Introduction | 1936 |

| Retired | 1945 |

| Primary users | Regia Aeronautica Japan Spain |

| Number built | Fiat BR.20 233 [1]

Fiat BR.20M 279 [2] |

|

| |

The Fiat BR.20 Cicogna (Italian: "stork") was a low-wing twin-engine medium bomber produced from the mid-1930s until the end of World War II by the Turin firm. When it entered service in 1936 it was the first all-metal Italian bomber [3] and it was regarded as one of the most modern medium bombers in the world.[4] It had its baptism of fire in summer 1937, with Aviazione Legionaria, during the Spanish Civil War, when it formed the backbone of Nationalist bombing operations along with the Heinkel He 111.[5] It was then used successfully by the Japanese during the Second Sino-Japanese War.[6] When Italy entered war in 1940, the BR.20 was the standard medium bomber of the Regia Aeronautica, but was approaching obsolescence. By 1942, it was mostly used for maritime patrol and operational training for bomber crews.[6] More than 500 were produced before the end of the war.[7]

Design and development

In 1934, the Regia Aeronautica requested Italian aviation manufacturers to submit proposals for a new medium bomber; the specifications called for speeds of 330 km/h (205 mph) at 4,500 m (15,000 ft) and 385 km/h (239 mph) at 5,000 m (16,400 ft), a 1,000 km (620 mi) range and 1,200 kg (2,600 lb) bombload. Piaggio, Macchi, Breda, Caproni and Fiat offered aircraft that mainly exceeded the speed requirements, but not range, and not all exhibited satisfactory flight characteristics or reliability. Accepted among the successful proposals, together with the trimotor Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 and Cant Z.1007, was the BR.20 Cicogna designed by Celestino Rosatelli, thus gaining the prefix BR, (for "Bombardiere Rosatelli").[8]

The BR.20 was designed and developed swiftly, with the design being finalized in 1935 and the first prototype (serial number M.M.274) flown at Turin on 10 February 1936.[9] Production orders were quickly placed, initial deliveries being made to the Regia Aeronautica in September 1936.

Technical description

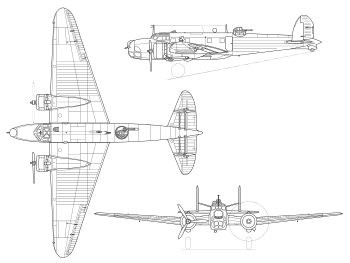

The BR.20 was a twin-engine low-wing monoplane, with a twin tail and a nose separated into cockpit and navigator stations. Its robust main structure was of mixed-construction; with a slab-sided fuselage of welded steel tube structure having duralumin skinning of the forward and center fuselage, and fabric covering the rear fuselage. The 74 m² (796 ft²) metal-skinned wings had two spars and 50 ribs (also made of duralumin), with fabric-covered control surfaces.[9] The hydraulically actuated main undercarriage elements retracted into the engine's nacelles, and carried 106 x 375 x 406 mm wheels. The takeoff and landing distances were quite short due to the low wing loading, while the thickness of the wing did not compromise the aircraft's speed. The twin tail allowed a good field of fire from the dorsal gun turret.[8]

The engines were two Fiat A.80 RC 41s, rated at 1,000 cv at 4,100 m (13,451 ft), driving three-blade Fiat-Hamilton metal variable-pitch propellers.[8] Six self-sealing fuel tanks in the center fuselage and inner wings held 3,622 Ls ( US gal) of fuel, with two oil tanks holding 112 L (30 US gal). This gave the fully loaded bomber (carrying a 3,600 kg/7,900 lb payload) an endurance of 5½ hours at 350 km/h (220 mph), and 5,000 m (16,400 ft) altitude. Takeoff and landing distances were 350 m (1,150 ft) and 380 m (1,250 ft) respectively. The theoretical ceiling was 7,600 m (24,930 ft).

Crewed by four or five, the BR.20's two pilots sat side by side with the engineer/radio operator/gunner behind. The radio operator's equipment included a R.A. 350-I radio-transmitter, A.R.5 receiver and P.3N radio compass.[10] The navigator/bomb-aimer had a station in the nose equipped with bombsights and a vertical camera. Another two or three crew members occupied the nose and the mid-fuselage, as radio-operator, navigator and gunners. The radio operator was also the ventral gunner while the last crew member was the dorsal gunner.[8]

Armament

The aircraft was fitted with a Breda model H nose turret carrying a single 7.7 mm (.303 in) Breda-SAFAT machine gun, and was initially fitted with a Breda DR dorsal turret carrying one or two 7.7 mm (.303 in) machine guns. This turret was unusual because it was semi-retractable: the gunner's view was from a small cupola, and in case of danger, he could extend the turret. This was later replaced by a Fiat M.I turret carrying a 12.7 mm (.5 in) Breda, then by a Caproni-Lanciani Delta turret mounting a 12.7 mm (.5 in) Scotti machine gun (although this was unreliable), and finally by a more streamlined Breda R, armed with a 12.7 mm (.5 in) Breda; this was a much better system that did not need to be retracted because of the lower induced drag. The aircraft was fitted with a further 7.7 mm (.303 in) machine gun in a ventral clamshell hatch that could be opened when required. The original defensive armament weighed 220 kg (480 lb).[8]

The BR.20's payload was carried entirely in the bomb bay in the following possible combinations: 2 × 800 kg (1,760 lb) bombs as maximum load, 2 × 500 kg (1,100 lb), 4 × 250 kg (550 lb), 4 × 160 kg (350 lb), 12 × 100 kg (220 lb), 12 × 50 kg (110 lb), 12 × 20 kg (40 lb), or 12 × 15 kg (30 lb) bombs. Combinations of different types were also possible, including 1 × 800 kg (1,760 lb) and 6 × 100 kg (220 lb), 1 × 800 kg (1,760 lb) and 6 × 15 or 20 kg (30 or 40 lb), or 2 × 250 kg (550 lb) and 6 × 50 or 100 kg (110 or 220 lb) bombs. The BR.20 could also carry four dispensers, armed with up to 720 × 1 or 2 kg (2 or 4 lb) HE or incendiary bomblets. All the bombs were loaded and released horizontally, improving the accuracy of the launch. No torpedoes were used.

By the time Italy had entered World War II, a new variant, the BR.20M, had been produced and put in service. The BR.20M had a different nose with added glazed sections for the bombardier and a slightly longer fuselage. Also, the weight was increased because part of the fabric was substituted with metal, improving the resistance to flutter while reducing speed from 430 km/h (270 mph) to 410 km/h (260 mph).[8]

Cicogna vs. Sparviero

Despite the BR.20 being the winner of the 1934 new bomber competition, the Savoia Marchetti SM.79 Sparviero, a non-competitor which was developed at practically the same time, gained a reputation that overshadowed the Cicogna, partly because of its performance in air-racing. The performance differences between the two aircraft were minimal: both were rated at about 430 km/h (270 mph), with maximum and typical payloads of 1,600 kg (3,630 lb) and 1,250 kg (2,760 lb) respectively for a range of 800–1,000 km (500-620 mi). Both also had three to four machine guns as defense weapons, but almost totally lacked protective armour.[8]

The reasons for the Sparviero's success lay in its flying characteristics. The Sparviero was a more difficult aircraft to fly with a heavier wingload, but overall its three engines gave more power than the two of the BR.20. The Sparviero, weighing around the same, had a reserve of power and was capable of performing acrobatic manoeuvers, even rolls. Its engines were more reliable than those of the BR.20 and had enough power to return to base even with one shut down. The Sparviero's superior agility enabled it to perform as a torpedo-bomber, while the Cicogna was never considered for that role.[8] Over 1,200 Sparvieros were built, at least twice as many as the Cicogna.

Operational history

When, at the end of 1936, the 13° Stormo Bombardamento Terrestre (in Lonate Pozzolo) was equipped with the "Cicognas" it was probably the most modern bombing unit in the world.[4] Shortly after entering service with the Regia Aeronautica, the aircraft became central to the propaganda campaign lauding Italian engineering. In 1937, two stripped-down BR.20s (designated BR.20A) were built for entry into the prestigious Istres–Damascus air race gaining sixth and seventh place when S.M.79s scored the first place, leaving the Fiats far behind. They had a rounded nose similar to civil aircraft, and had all military hardware, such as defensive turrets, removed. The internal fuel capacity was increased to 7,700 L (2,034 US gal), bringing the maximum range to 6,200 km (3,850 mi).[8] In 1939, a modified long-range BR.20 version (designated BR.20L) named Santo Francesco under the command of Maner Lualdi made a highly publicised nonstop flight from Rome to Addis Ababa at an average speed of 390 km/h (240 mph).[11][12] It carried 5,000 l (1,321 US gal) of fuel, increasing the range from 3,000 km (1,864 mi) to 4,500 km (2,800 mi).

The main task of the BR.20 was medium-range bombing. It had many features that were very advanced for its time: with a maximum speed of over 400 km/h (250 mph) and a high cruise speed of 320 km/h (200 mph), it was as fast as aircraft like the Tupolev SB light bombers. The range and payload were also very good.

Spain

Italy deployed six BR.20s to Spain in June 1937 for use by the Aviazione Legionaria to fight in support of Francisco Franco's Nationalist forces in the Spanish Civil War,[13] with a further seven aircraft sent to Spain in July 1938.[11] They took part in bombing raids over Teruel and at the Battle of the Ebro, proving to be sturdy and accurate bombers. The BR.20s were fast enough to generally avoid interception from the Republican Polikarpov I-16s and I-15s. Losses were very low; nine of the 13 BR.20s sent to Spain survived to the end of the war when they were handed over to the Spanish State to serve with the Ejército del Aire (EdA).

While the Cicognas were successful, just 13 examples were sent to Spain compared to at least 99 SM.79s, which meant that the Sparviero was almost the Italian standard bomber, especially on day missions.[8]

Japan

In July 1937, when Japan entered into full-scale war with China (the Second Sino-Japanese War), the Japanese Army Air Force found itself short of modern long-range bombers pending delivery of the Mitsubishi Ki-21 "Sally", which was undergoing prototype trials, and so required an interim purchase of aircraft from abroad. Italy was willing to give priority to any Japanese orders over its own requirements, and offered the Caproni Ca.135 and the BR.20. While the Caproni could not meet the Japanese requirements, the BR.20 closely matched the specification, and so an initial order was placed in late 1937 for 72 Br.20s, soon followed by an order for a further 10 aircraft.[14]

Deliveries to Manchuria commenced in February 1938, with the BR.20 (designated the I-Type (Yi-shiki)) replacing the obsolete Mitsubishi Ki-1, equipping two bomber groups (the 12th and 98th Sentai), which were heavily deployed on long-range bombing missions against Chinese cities and supply centers during the winter of 1938–39. The BR.20s were operating with no fighter cover at the extremes of their range and consequently incurred heavy losses from Chinese fighters, as did the early Ki-21s that shared the long-range bombing tasks.[14]

The fabric-covered surfaces were viewed as vulnerable, even if the main structure of this aircraft was noticeably robust. The aircraft had unsatisfactory range and defensive armament, but the first Ki-21s that entered service were not much better, except for their all-metal construction and the potential for further development when better engines became available (both types initially used two 746 kW/1,000 hp engines).

The 12th Sentai was redeployed to the Mongolian-Manchurian border to fight in the Battle of Khalkhin Gol, but when this conflict ended, in September 1939, the BR.20s were progressively withdrawn and replaced by the Ki-21.[14] Despite having been phased out from operational service, the BR.20 was allocated the Allied reporting name "Ruth".[15]

World War II

Following Nazi Germany's invasion of France in May 1940, and with German forces pushing deep into France, Italy declared war on France and the United Kingdom on 10 June 1940. At this time, only four wings operated BR.20s compared to the 14 wings equipped with SM.79s, with 172 Cicognas being in service with the Regia Aeronautica including those not yet delivered to operational squadrons.[16] The units equipped with the Cicogna were the 7°, 13°, 18° and 43° Stormo (Wing), all based in Northern Italy.

France

The aircraft of the 7°, 13° and 43° Stormo fought in the brief campaign against France. On the night of 12 June 1940, eight bombers from 13° attacked Toulon dockyard. The next day, 10 Fiat BR.20s dropped bombs on Hyères and Fayence airfields; two aircraft (commanded by Catalano and Sammartano) were shot down and one was badly damaged. The same day, 28 BR.20s from 43° and 7° Stormo bombed Toulon again, with no losses.[17] On 15 June, one BR.20M (Matricola Militare MM. 21837) of the newly formed 172a Squadriglia Ricognizione Strategica Terrestre based on Bresso airfield, was shot down over Provence [17] by Dewoitine D.520s, the French air defenses in the south having not been defeated by the German attack in the north. Small-scale air raids continued until the French surrender, with many BR.20s also used in support for the Army - bombing Briançon, Traversette and Cap San Martin fortresses on the Alps - and as reconnaissance aircraft.[8][16] At the end of the French campaign, five BR.20s had been lost and 19 airmen killed.[17]

Britain

It was against the British over the Channel that the BR.20 showed its limitations for the very first time.[18] On 10 September 1940, the Corpo Aereo Italiano was formed, with 13° and 43° Stormi equipped with 80 brand-new BR.20Ms, to fight in the Battle of Britain.[17] During the ferry operation from Italy to their bases in Belgium, five aircraft crash-landed because of technical failures and a further 17 were forced to land en route due to poor visibility.[19] On the night of 24 October, the 13° and 43° took off for their first bombing mission, over Harwich, with eight BR.20s each. One plane crashed on take off, because of engine failure, while two more got lost on their return, failing to find their airfield and their crews bailing out. On 29 October, 15 aircraft of 43° Stormo bombed Ramsgate, in daylight, with no loss.[19] In a famous battle on 11 November, a formation of 10 BR.20s from 43° Stormo, escorted by Fiat CR.42 biplane fighters – but not by the Fiat G.50s - on a daylight raid on Harwich, was intercepted by Royal Air Force Hurricanes. Despite the escort, three bombers were downed (together with three CR.42s) and three more damaged,[19] with no loss to the Hurricanes.[16] Winston Churchill commented on this raid, which occurred on the same day as the Fleet Air Arm's attack on Taranto: "They might have found better employment defending their Fleet at Taranto."[20]

The BR.20s of the Corpo Aereo Italiano nevertheless bombed Ipswich and Harwich on the nights of 5, 17, 20, 29 November, three times in December and twice at the beginning of January, with no loss. On 10 January 1941, the 43° Stormo flew back to Italy, followed by the 13° before the end of the month. During 12 days of bombing missions, the “Cicognas” dropped 54,320 kg; three aircraft were lost to enemy fire, 17 more for other reasons and 15 airmen were killed.[19][21] Still, almost 200 modern aircraft were involved, weakening the Regia Aeronautica's presence in the Mediterranean.

North Africa

On 27 February 1941, 14 Cicogne of 98° Gruppo, 43° Stormo, that had been in service with Corpo Aereo Italiano in Belgium, led by commander De Wittembeschi, left Italy bound for Tripolitania, in Libya. On 11 March they landed on Castel Benito airfield. Subsequently they were allocated to Bir Dufan base, where they replaced the Savoia-Marchetti SM.81s.[22] The BR.20s were tasked to bomb the British forces, in particular the key port of Tobruk. North Africa was never a primary theater for the Cicogna, but 13 Stormo (Wing) was sent there to continue the night attacks against the British in July 1941–April 1942.[8] One of the last sorties occurred on 7 March 1942, when two Fiats machine-gunned Arab troops serving with the British near Oberdan village, subsequently 11° and 43° Gruppi started withdrawal to Italy. By 12 April the whole Stormo was back to Reggio Emilia base: during the African campaign, with the type suffering many mechanical troubles because of the desert sand, losses amounted to 15 Cicogne.[22]

The last use over Africa was when 55° Gruppo aircraft contested Operation Torch.[8]

Malta

BR.20s were used in the Malta campaign in 1941, 1942 and 1943. On 7 May 1941, 19° Gruppo from 43° Stormo, left Lonate Pozzolo with eight aircraft and arrived in Gerbini, Sicily. On 22 May the BR.20s started to carry out raids against the besieged island almost nightly. The first loss occurred on 8 of June. On 9 June, the 31° Gruppo arrived from Aviano, with 18 bombers,[23] but in less than three months the units lost 12 BR.20s. In October the 37° Stormo arrived in Sicily with the 116° Gruppo, based on Fontanarossa airfield, and the 55° Gruppo, in Gerbini. But in the first month those units too lost nine aircraft, due to accidents or enemy fire.[24]

Attrition remained high, and BR.20 units continued to be rotated to bases on Sicily to continue the offensive against Malta though 1941 and 1942.[8][25]

On 1 May 1942, the 88° Gruppo landed in Castelvetrano with 17 new machines (one crash landed on the Appennini Mountains). The units started operational service on 8 May, dropping 4AR mines. Before the end of August, five aircraft were lost and that same month the BR.20s left Sicily. In the 16 months of their Malta campaign, 41 “Cicognas” were shot down or lost through accidents. The Fiat bombers returned for a short time in 1943 with attacks on Malta.[23]

Soviet Union

Several BR.20s were sent to the Soviet Union in August 1942, to perform long-range reconnaissance and bombing sortie in support of CSIR, Italian Army on Eastern Front. On 3 August 1941, two BR-20s arrived in Ukraine and were assigned to 38a Squadriglia osservazione aerea (reconnaissance squadron) of 71° Gruppo. Three days later they had their baptism of fire, bombing enemy troops at Werch Mamor, along Don river. More BR.20s arrived on 5 September from 43° Stormo. Three of them were assigned to 116a Squadriglia. They usually flew alone bombing sorties, carrying 36 small-baskets of incendiary bombes to drop on enemy troops in urban areas. On 5 October, three Mikoyan Mig-1s and a Yakovlev Yak-1 attacked the BR.20 flown by Capitano Emilio d’Emilei. The Fiat crew claimed two Soviet fighters and the bomber managed to land back to airfield, in Kantemirovka, in Voronež Oblast', but the pilot was wounded. The BR.20s were withdrawn from eastern Front in spring 1943, at first to Odessa and, subsequently, to Italy, on 13 April. [26]

Other fronts

During the course of the war, BR.20s were used in Albania and Greece as well. They were also used extensively in Yugoslavia against Josip Broz Tito's partisans. Other BR.20s were used to drop food and other material to the Italian Army, often trapped in the Balkans, faced with Yugoslavian resistance.[8]

After the first year of war, the limitations of this type were evident. It was highly vulnerable to enemy attacks, as Japanese experience had shown in 1938, and the aircraft was replaced by the Cant Z.1007 and Savoia-Marchetti SM.84 in almost all operational units that had employed the BR.20.

By 1943, when the Italian armistice was signed, many had been relegated to training, although 81 were with operational units, mostly in the Balkans and Italy; also later serving on the Eastern Front.

Italy invaded Greece in October 1940, and deployed increasing numbers of BR.20s in attacks on Greece from bases in Italy and Albania in support of the Italian Army while it was being driven back into Albania. They were involved in heavy battles with the Greeks and British, often facing fierce RAF opposition, as happened on 27 February 1941, when four BR.20s were lost or heavily damaged. This force was redeployed against Yugoslavia during the more successful German and Italian invasion in April 1941,[25] using a strong detachment (131 aircraft) in four groups.[8]

While the main front line task remained that of night bombing, especially against Malta, other roles included reconnaissance and the escort of convoys in the Mediterranean. For escort duties, aircraft were fitted with bombs and possibly depth charges, but with no other special equipment. They were used in this role from 1941, with 37° Wing (Lecce), 13° Wing (end of 1942), 116°, 32 Group (Iesi, from 1943), and 98° (based in Libya) from 1941. One of the 55° aircraft was lost in August 1941 against British torpedo bombers, while between 9 August–11 September 1941, 98° escorted 172 ships from Italy to Libya. In almost all these units, the Cicogna was operated together with other aircraft, such as the Caproni Ca.314. This escort task was quite effective, at least psychologically, although the Cicogna was hampered by the lack of special equipment and, consequently, no submarines were sunk.

At the time of the September 1943 Armistice between Italy and the Allies, 67 BR.20s were operational with front line operational units, mainly being used on anti-partisan operations,[27] although most aircraft had been relegated to the training role. During the final years of the war, some surviving aircraft remained in use as trainers and transports. A small number were used by the RSI after the Armistice, with only one retained by the Italian Co-Belligerent Air Force, which used it for communications duties.[27] The last BR.20 was retired on 7 June 1946 and none survive today.

Final developments

BR.20 was a good overall design, but it soon became obsolete, and the lack of improved versions condemned it to be only a second-line machine, underpowered and lacking in defensive firepower.

The final production variant was the BR.20bis which was a complete redesign. It had a fully glazed nose, a retractable tail wheel, and more streamlined fuselage, pointed fins, although the main change was increased engine power from two 932 kW (1,250 hp) Fiat A.82 RC 42 radial engines and improved and heavier armament. The nose held a simple machine gun position rather than the turret used on earlier aircraft and two waist blisters were fitted over the wing trailing edge while the dorsal turret was a Breda Type V instead of the earlier Caproni Lanciani type. While this was considered to be an improvement over the previous versions, planned production was limited, as the Regia Aeronautica had placed large orders for the CRDA CANT Z.1018. Originally, 98 were ordered, but only 15 BR.20bis were built from March to July 1943, with heavy Allied bombing of Fiat's Turin factory preventing further production.[27] There is no evidence that they were used operationally.

Experimental versions included the BR.20C, a gunship with a 37 mm (1.46 in) cannon in the nose and another aircraft was modified with a tricycle undercarriage. Another was modified to guide radio-commanded unmanned aircraft filled with explosives, but this was never used in combat.[8]

Including those sold to Japan, at least 233 standard BR.20s were made, along with 264–279 BR.20Ms being built from February 1940.

Variants

- BR.20

- Initial production model, 233 built.[28]

- BR.20A

- De-militarised conversion of two BR.20s for air racing.

- BR.20L

- Long ranged civil version, one built.

- BR.20M

- Improved bomber version with lengthened nose, 264 produced.[28]

- BR.20C

- Single aircraft converted by Agusta fitted with 37 mm (1.46 in) cannon in revised nose.

- BR.20bis

- Major re-design with more powerful engines (two Fiat A.82 RC.42 rated at 932 kW/1,250 hp each), increased dimensions and new, fully glazed nose.

Operators

- A single captured BR.20 entered service with the Republic of China Air Force in 1939.[29]

- Venezuelan Air Force - A single BR.20 was sold to Venezuela.[28]

Specifications (Fiat Br.20M)

Data from The Encyclopedia of Weapons of World War II[30]

General characteristics

- Crew: 5

- Length: 16.68 m (54 ft 8 in)

- Wingspan: 21.56 m (70 ft 8.75 in)

- Height: 4.75 m (15 ft 7 in)

- Wing area: 74.0 m² (796.5 ft²)

- Empty weight: 6,500 kg (14,330 lb)

- Max. takeoff weight: 10,100 kg (22,270 lb)

- Powerplant: 2 × Fiat A.80 RC.41 18-cylinder radial engine, 746 kW (1,000 hp) each

Performance

- Maximum speed: 440 km/h (273 mph)

- Cruise speed: 340 km/h (211 mph)

- Range: 2750 km (1,709 mi)

- Service ceiling: 8,000 m (26,250 ft)

Armament

- Guns: 3× 12.7 mm (.5 in) Breda-SAFAT machine guns

- Bombs: 1,600 kg (3,530 lb) of bombs

See also

- Related lists

- List of Interwar military aircraft

- List of aircraft of World War II

- List of Regia Aeronautica aircraft used in World War II

- List of bomber aircraft

References

- Notes

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ Bignozzi, p. 10.

- 1 2 Gunston 1994, p. 221.

- ↑ Ethell 1995, p. 66.

- 1 2 Ethell 1995, p. 67.

- ↑ Matricardi 2006, p. 257.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Lembo 2003, p. 8-26.

- 1 2 Green and Swanborough 1982, p. 291.

- ↑ Green and Swanborough 1982, p. 292.

- 1 2 Green and Swanborough 1982, p. 307.

- ↑ Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI) - General Aviation World Records: History of General Aviation World Records List of records established by the 'Fiat B.R.20.' Retrieved: 1 December 2007.

- ↑ Green and Swanborough 1982, p. 293.

- 1 2 3 Green and Swanborough 1982, p. 294.

- ↑ Taylor 1980, p. 384.

- 1 2 3 Green and Swanborough 1982, p. 308.

- 1 2 3 4 De Marchi 1976, p. 6.

- ↑ Angelucci and Matricardi 1978, p. 197.

- 1 2 3 4 De Marchi 1976, p. 7.

- ↑ "David Scott Malden." skynet.be. Retrieved: 7 December 2007.

- ↑ Green and Swanborough 1982, p. 310.

- 1 2 De Marchi 1976, p. 10.

- 1 2 De Marchi 1976, p. 8.

- ↑ De Marchi 1976, p. 9.

- 1 2 Green and Swanborough 1982, p. 311.

- ↑ De Marchi 1976, p. 12.

- 1 2 3 Green and Swanborough 1982, p. 312.

- 1 2 3 Donald 1997, p. 407-408.

- ↑ Andersson 2008, p. 266.

- ↑ Bishop, Chris, ed. The Encyclopedia of Weapons of World War II. New York: Barnes & Noble, 1998. ISBN 0-7607-1022-8.

- Bibliography

- Andersson, Lennart.A History of Chinese Aviation: Encyclopedia of Aircraft and Aviation in China until 1949. AHS of ROC: Taipei, Taiwan, 2008. ISBN 978-957-28533-3-7.

- Angelucci, Enzo and Paolo Matricardi. World Aircraft: World War II, Volume I (Sampson Low Guides). Maidenhead, UK: Sampson Low, 1978. ISBN 0-562-00096-8.

- Bignozzi, Giorgio. Aerei d'Italia (dal 1923 al 1972). Edizioni "E.C.A. 2000" Milano.

- De Marchi, Italo. Fiat BR.20 cicogna. Modena, Editore S.T.E.M. Mucchi, 1976.

- Donald, David, ed. The Encyclopedia of World Aircraft. Aerospace Publishing. 1997. ISBN 1-85605-375-X.

- Ethell, L. Jeffrey. Aircraft of World War II. Glasgow, HarperCollins Publishers, 1995. ISBN 0-00-470849-0.

- Green, William and Swanborough, Gordon, eds. "Fiat BR.20... Stork à la mode". Air International Volume 22, No. 6, June 1982, pp. 290–294, 307–312. ISSN 0306-5634.

- Gunston, Bill. Aerei della Seconda Guerra Mondiale. Milano, Alberto Peruzzo Editore, 1984.

- "Il CAI sul Mare del Nord" (in Italian). RID magazine October 1990.

- Lembo, Daniele. "Fiat BR.20 una Cicogna per la Regia" (in Italian). Aerei nella Storia n. 29, April–May 2003, West-ward edictions.

- Matricardi, Paolo. Aerei Mililtari: Bombardieri e da Trasporto 2.(in Italian) Milano, Electa Mondadori, 2006.

- Massiniello, Giorgio. "Bombe sull'Inghilterra" (in Italian). Storia Militare magazine n.1/2005.

- Mondey, David. The Hamlyn Concise Guide to Axis Aircraft of World War II. London: Bounty Books, 2006. ISBN 0-7537-1460-4.

- Sgarlato, Nico. "Il Disastro del CAI" (in Italian). Aerei nella Storia magazine, June 2007.

- Taylor, M.J.H. (ed). Jane's Encyclopedia of Aviation. London: Jane's, 1980. ISBN 1-85170-324-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fiat BR.20. |

- A Spanish Civil War photo showing an early model BR.20

- BR.20 on Avions legendaires (French)

- Comando Supremo on BR.20