Species of Galápagos tortoise

| Galápagos tortoises | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chelonoidis nigra skeleton at the National Museum of Natural History in Washington DC | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Sauropsida |

| Order: | Testudines |

| Family: | Testudinidae |

| Genus: | Chelonoidis |

| Species: | C. nigra |

| Binomial name | |

| Chelonoidis nigra[2] (Quoy & Gaimard, 1824) | |

| Synonyms | |

(Harlan, 1827) | |

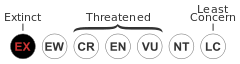

Chelonoidis nigra (the Galápagos tortoise) is a tortoise species complex endemic to the Galápagos Islands. It includes at least 12, and possibly up to 15, species.[3] Only twelve species now exist: one on each of the islands of Santiago, Santa Cruz, San Cristóbal, Pinzón, and Española; one on each of the five main volcanoes of the largest island Isabela (Wolf, Darwin, Alcedo, Sierra Negra, and Cerro Azul); and one, abingdoni from Pinta Island, which is considered extinct as of June 24, 2012. The species inhabiting Floreana Island (C. n. nigra) is thought to have been hunted to extinction by 1850,[4][5] only years after Charles Darwin's landmark visit of 1835 in which he saw carapaces but no live tortoises on the island.[6]

Biological taxonomy is not fixed, and placement of taxa is reviewed as a result of new research. The current categorization of species of Chelonoidis nigra is shown below. Also included are synonyms, which are now discarded duplicate or incorrect namings. Common names are given but may vary, as they have no set meaning.

List of species

| Species [1][7] | Authority | Description | Population and range[8] |

|---|---|---|---|

| C. abingdoni (from Abingdon Island) Abingdon Island tortoise

|

Günther 1877.[9] The holotype of C. n. ephippium (Günther 1875) is a misidentified C. n. abingdoni,[10] so technically abingdoni is a junior synonym. | Lonesome George, the last living member, died June 2012. This species was severely depleted by whalers and fishermen, and the introduction of goats in 1958 resulted in massive destruction of vegetation. The carapace is shaped like a saddle, very narrow, compressed, and slightly upturned anteriorly, and wider and lower posteriorly with a rounded margin. | No known individuals. Formerly the southern slopes of Pinta (Abingdon) island, now extinct. In 2007, a Pinta hybrid was found on Isabela Island,[11] suggesting that there may be an Abingdon tortoise in the wild. |

| C. becki (named for Rollo Beck) Volcán Wolf tortoise |

Rothschild 1901[12] | Reproduction is successful. Apparently two morphotypes occur on Volcan Wolf, domed and saddle-backed. A more flattened or dome-shelled population from the south may have crossed the former lava barrier and mixed with an isolated population of saddlebacked tortoises.[10] For the saddlebacked variety, the gray, carapace is relatively thick with little or no cervical indentation, the anterior carapacial rim upturned, and the posterior marginals flared and slightly serrated. The carapace is compressed or narrowed anteriorly, but not nearly as much as some other saddlebacked species. | 1,139 individuals. Northern Isabela (Albermarle) Island, northern and western slopes of Volcano Wolf.

Recent research indicates that the variation is caused by hybridization of native Isabela tortoises with about 40 descendents of tortoises from Floreana, a population thought to be extinct since the 1850s.[13] |

| C. chathamensis (from Chatham Island) Chatham Island tortoise |

Van Denburgh 1907[14] | Heavily exploited and completely eliminated over much of its original range. Trampling of nests by feral donkeys, and the predation of young by feral dogs decimated populations, but the breeding program had led to successful releases. It has a wide, black shell, its shape intermediate between the saddlebacked and domed species: adult males are rather saddlebacked, but females and young males are wider in the middle and more domed. A now extinct, more flat-shelled form occurred throughout the wetter and higher regions of the island most altered by man when the island was colonized. The type specimen was from this extinct population, so it is possible that the species currently designated C. chathamensis is mistakenly applied.[7] | 1,824 individuals. San Cristóbal (Chatham) island, confined to the northeast. Fencing of nests and dog eradication in the 1970s helped population recovery.[15] |

| C. darwini (named for Charles Darwin) James Island tortoise |

Van Denburgh 1907[14] | Large numbers of tortoises were removed from the island in the early nineteenth century by whaling vessels, and introduced goats reduced the coastal lowlands to deserts, restricting the remaining tortoises to the interior. The sex ratio is strongly imbalanced in favour of the males and most nests and young are destroyed by feral pigs. Some nests are now protected by lava corrals and since 1970 eggs have been transported to the Charles Darwin Research Station for hatching and rearing. Release programs and measures for nest protection from feral pigs have been successful.[15] The gray to black carapace is intermediate in shape between the saddlebacked species and those with domed shells. It has only a shallow cervical indentation; the anterior carapacial rim is not appreciably upturned, and the posterior marginals are flared, slightly upturned, and slightly serrated. | 1,165 individuals though a strong male bias in the remaining population impedes a quick recovery of the population. Santiago (James) Island, west-central areas. |

| C. duncanensis (from Duncan Island) Duncan Island tortoise |

Garman 1917[16] syn. ephippium (L. 'mounted as on a horse, saddlelike') Günther 1875.[17] The holotype of C. n. ephippium is a misidentified C. n. abingdoni.[10] The previous nomen nudum for the taxon, duncanensis was therefore resurrected. |

Although relatively undisturbed by whalers, fairly large numbers of tortoises were removed by expeditions in the latter half of the nineteenth century and early twentieth. After the introduction of black rats (Rattus rattus) and Norway rats (Rattus norvegicus)[18] some time before 1900, no natural breeding succeeded. Since 1965, eggs have been transported to the Charles Darwin Research Station for hatching and rearing. Over 75% of those released between 1970 and 1990 survived.[15] This saddlebacked species is one of the smallest of the Galápagos tortoises. Its brownish gray, oblong carapace has only a very shallow cervical indentation, the anterior marginals little to much upturned, and the slightly serrated posterior marginals flared and upturned. The carapace is usually compressed or narrowed anteriorly. | 532 individuals (no longer extinct in the wild). Southwestern Pinzón (Duncan) Island. |

| C. guentheri (named for Albert Günther) Sierra Negra tortoise |

Baur 1889[19] | Severely depleted by settlement and exploitation for tortoise oil which continued until the 1950s. The wild reproduction is successful in the east but in the western-southwestern area pigs, dogs, rats and cats are present as predators. It is one of the most threatened of the existing species, and 20 adults were taken into captivity for a breeding program in 1998 following the threat of a volcanic eruption from the nearby Cerro Azul Volcano.[20] The species is intermediate in shape between domed and saddlebacked, with a distinctive 'tabletop' appearance. At least one authority has suggested merging C. vicina with C. microphyes, C. vandenburghi and C. guentheri[10] as the Southern Isabela subspecies, putting morphological differences down to geographical variation. | 694 individuals. Isabela Island by Sierra Negra Volcano, one group in the east and another over the western and southwestern slopes. |

| C. hoodensis (from Hood Island) Hood Island tortoise |

Van Denburgh 1907[14] | This population was very heavily exploited by whalers in the nineteenth century and collapsed around 1850. 13 adults were found in the early 1970s and held at the Charles Darwin Research Station as a breeding colony. The 2 males and 11 females were initially brought to the Darwin Station. Fortuitously, a third male was discovered at the San Diego Zoo and joined the others in a captive breeding program. Mating had not occurred naturally for some time because the individuals were so scattered that they did not meet. It is one of the smallest species. Its black, saddleback carapace has a deep cervical indentation, the anterior rim only weakly upturned, and posterior marginals downturned and slightly serrated. It is narrow anteriorly and wider posteriorly. | 860, Española (Hood) Island. |

| C. microphyes (L. 'small in stature') Volcán Darwin tortoise |

Günther 1875[17] | Heavily exploited in the nineteenth century by whaling vessels, but wild reproduction is successful. Has a brownish gray, oval carapace is intermediate between saddlebacked and domed and rather flattened. At least one authority has suggested merging C. vicina with C. microphyes, C. vandenburghi and C. guentheri[10] as the Southern Isabela species, putting morphological differences down to geographical variation. | 818 individuals. Isabela Island, southern and western slopes of Volcano Darwin |

| C. nigra (L. 'black') Floreana Island/Charles Island tortoise |

Quoy & Gaimard 1824[21] syn. galapagoensis Baur 1889.[19] This is the nominate species, sharing a name with the species. |

Formerly abundant but heavily exploited by visiting ships and a penal colony in the twentieth century. Darwin saw them in 1835, and noted that tortoises comprised the main food item in the Floreana colony; "two days hunting will find food for the other five in the week." Just three years later, a visiting ship could find no tortoises and in 1846, another visitor declared them extinct. Descriptions of the Floreana race are based on skeletal material from individuals who fell down into lava tubes and died.[22] However in 2008, research into mitochondrial DNA in museum specimens found some of the Floreana species. Theoretically, a breeding programme could be established to "resurrect" the pure Floreana race from hybrids. Using marker-assisted selection for a captive breeding population, it is estimated that the project would last a century.[23] | 0 individuals: extinct. Possible hybrid subpopulation exists on Isabela. Recent research found more than 80 tortoise hybrids between native Isabela tortoises and pure C. n. nigra, indicating that there might be about 38 pure descendents of tortoises from Floreana, perhaps transported by whalers.[24] |

| C. phantastica (L. 'a product of fantasy') Narborough Island tortoise |

Van Denburgh 1907[14] | Known from only one male specimen found (and killed) by members of the 1906 California Academy of Sciences expedition. There was a discovery of putative tortoise droppings in 1964. However, no other tortoises or even remains have been found on Fernandina and it is entirely possible that that one lone male was a stray or a release. Fernandina is the most pristine of the islands and any tortoise population would not be likely to have become extinct at the hands of introduced animals. If C. phantastica was, indeed, a real species, then it is the only one to become extinct by natural means.[22] | Fernandina (Narborough) Island (purportedly) |

| C. porteri Indefatigable Island tortoise |

Rothschild 1903[25] syn. nigrita (L. 'black') Duméril and Bibron 1835.[26] The IUCN[1] follows the nomenclature of Pritchard,[10] which determines that nigrita was a nomen dubium at the subspecific level and placed the taxon under C. nigra. |

Depleted by heavy exploitation for oil at least until the 1930s. Reproductive success severely hampered for many years by the presence of feral dogs and pigs, but breeding programs are steady. MtDNA evidence shows that there are actually three genetically distinct populations on Santa Cruz island. They are characterised by black, oval carapace (to 130 cm) is domed, higher in the centre than in the front, and broad anteriorly. In 2015, the small, eastern Cerro Fatal population of the island was described as a distinct taxon, donfaustoi, most closely related to chathamensis (and forming a clade with it plus abingdoni and hoodensis), while the main southwestern porteri population was found to be closer to the Floreana and southern Isabela tortoises.[27][28] | 3,391 individuals. Santa Cruz (Indefatigable) Island. The main population occurs in the southwest with smaller populations in the northwest and east. |

| C. vandenburghi (named for John Van Denburgh) Volcán Alcedo tortoise |

DeSola 1930[29] | The largest population in the archipelago, wild reproduction successful. It has a domed, black carapace. At least one authority has suggested merging C. vicina with C. microphyes, C. vandenburghi and C. guentheri[10] as the Southern Isabela species, putting morphological differences down to geographical variation. | 6,320 individuals (by far the most numerous population of C. nigra). Central Isabela Island on the caldera and southern slopes of the Alcedo Volcano. |

| C. vicina (L. 'near') Iguana Cove tortoise |

Günther 1875[17] syn. elephantopus | Range overlaps with C. guentheri. This population was depleted by seamen in the last two centuries and by extensive slaughter in the late 1950s and 1960s by employees of cattle companies based at Iguana Cove. It has a thick, heavy shell intermediate between saddlebacked and domed, and not appreciably narrowed anteriorly. Males are larger and more saddlebacked; females are more domed. Until eradication programs, virtually all nests and hatchlings were destroyed by black rats, pigs, dogs, and cats.[30] | 2,574 individuals. Isabela Island's Cerro Azul volcano, range may overlap that of C. n. guentheri. At least one authority has suggested merging C. vicina with C. microphyes, C. vandenburghi and C. guentheri[10] as the Southern Isabela species, putting morphological differences down to geographical variation. |

Disputed species

| Species | Authority | Description | Range and population[31] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Not described Santa Fe Island tortoise |

N/A | There are only 2 records of whalers removing tortoises, and there are two eye-witness accounts of locals removing tortoises in 1876 and 1890. These accounts, however, were given 15 and 30 years after the incident. Expeditions found old bones but no shell fragments, the most durable part of a tortoise skeleton, casting strong doubt on the validity of this species.[22] | Santa Fe Island (purportedly) |

| C. wallacei Rábida Island tortoise |

Rothschild 1902[32] | This putative species is known from only one specimen. Tracks were seen on Rabida in 1897 and a single individual was removed by the Academy of Sciences in 1906. No logs from whaling or sealing vessels make any mention of collecting at Rabida. Rabida has a good anchorage and near which is found a corral in which tortoises, perhaps from other islands, were temporarily held. The type specimen of C. n. wallacei, the individual from which the race was named, actually has an unknown provenance: it was assigned to Rabida because it resembled the one removed in 1906.[22] | Rabida Island (purportedly) |

References

- 1 2 3 Tortoise & Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group (1996). "Chelonoidis nigra". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2009.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved April 1, 2010.

- ↑ Rhodin (2010). "Turtles of the World 2010 Update: Annotated Checklist of Taxonomy, Synonymy, Distribution and Conservation Status" (PDF). Chelonian Research Foundation.

- ↑ Caccone (2002). "Phylogeography and history of the giant Galapagos tortoises". Evolution. pp. 2052–2066. JSTOR 3094648.

- ↑ Broom (1929). "On the extinct Galápagos tortoise that inhabited Charles Island". Zoologica: 9:313–320.

- ↑ Steadman (1986), "Holocene vertebrate fossils from Isla Floreana, Galápagos" (PDF), Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology (413), pp. 1–103, doi:10.5479/si.00810282.413

- ↑ Sulloway 1984. Darwin and the Galápagos. In: Berry, R.J. (Ed.) Evolution in the Galápagos Islands. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 21(1-2):29-60.

- 1 2 Pritchard (1979), Encyclopedia of turtles, Neptune, New Jersey: T. F. H. Publ., Inc.,

- ↑ "Galapagos Giant Tortoise". galapagospark.org. Retrieved 2010-08-30.

- ↑ Günther 1877 . The gigantic land tortoises (living and extinct) in the collection of the British Museum, British Museum (Nat. Hist.), London

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Pritchard 1996. The Galapagos tortoises: Nomenclatural and survival status. Chelonian Research Monographs. (1):1–85

- ↑ DNA search gives hope to tortoise. BBC News. (Accessed 2012-01-14.)

- ↑ Rothschild 1901. On a new land-tortoise from the Galapagos Islands Novitates Zoologicae

- ↑ Extinct tortoise 'can live again'. BBC News. (Accessed 2012-01-14.)

- 1 2 3 4 Van Denburgh, John (1907). "Preliminary descriptions of four new races of gigantic land tortoises from the Galapagos Islands". Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences. 4th series. 1: 1–6.

- 1 2 3 Cayot 1994. Conservation biology of Galápagos reptiles: twenty-five years of successful research and management. In: J. B. Murphy, K. Adler, and J. T. Collins (eds.). Captive Management and Conservation of Amphibians and Reptiles, pp. 297–305. Ithaca, New York: Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. Contributions to Herpetology. vol. 11. ISBN 0-916984-33-8.

- ↑ Garman 1917. The Galapagos tortoises. Memoirs of the Museum of Comparative Zoölogy at Harvard College., vol. XXX, no. 4

- 1 2 3 Gunther 1875. Description of the Living and Extinct Races of Gigantic Land-Tortoises. Parts I. and II. Introduction, and the Tortoises of the Galapagos Islands, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Biological Sciences, 165, pp.251-84

- ↑ Rat eradication program begins in Galapagos Islands. Scientific American. (Accessed 2012-01-14.)

- 1 2 Baur 1889. The gigantic land tortoises of the Galapagos Islands. The American Naturalist 23:1039–1057

- ↑ "Turtle Action News". Tortoise.org. Retrieved 2008-10-14.

- ↑ Quoy and Gaimard 1824. Sous-genre Tortue de Terre -- Testudo. Brongn. Tortue Noire -- Testudo nigra. N. In: M. L. de Freycinet (ed.), Voyage autour du Monde executé sur l'Uranie et la Physicienne pendent les années 1817-1820, pp. 174-175.

- 1 2 3 4 "Galapagos Giant Tortoises". rit.edu. Archived from the original on 10 January 2010.

- ↑ Poulakakis 2008. Historical DNA analysis reveals living descendants of an extinct species of Galapagos tortoise. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105:15464-15469

- ↑ Extinct tortoise can live again, BBC News. (Accessed 2011-01-14)

- ↑ Rothschild 1903. Description of a new species of gigantic land tortoise from Indefatigable Island. Novitates Zool. 10: 119.

- ↑ Duméril and Bibron 1835. Erpétologie générale ou histoire naturelle complete des reptiles. Vol. 2. Libraire Encyclopedique de Roret, Paris.

- ↑ Marris, E. (2015-10-21). "Genetics probe identifies new Galapagos tortoise species". Nature News. Nature Publishing Group. Retrieved 2015-10-23.

- ↑ Poulakakis, N.; Edwards, D. L.; Chiari, Y.; Garrick, R. C.; Russello, M. A.; Benavides, E.; Watkins-Colwell, G. J.; Glaberman, S.; Tapia, W.; Gibbs, J. P.; Cayot, L. J.; Caccone, A. (2015-10-21). "Description of a New Galapagos Giant Tortoise Species (Chelonoidis; Testudines: Testudinidae) from Cerro Fatal on Santa Cruz Island". PLOS ONE. 10 (10): e0138779. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0138779.

- ↑ DeSola 1930. The Liebespiel of Testudo vandenburghi, a new name for the mid-Albemarle Island Galápagos tortoise. Copeia. 1930:79–80

- ↑ MacFarland 1974a. The galapagos giant tortoises (Geochelone elephantopus). I. Status of the surviving populations. Biological Conservation. 6(2):118–133

- ↑ "Galapagos Giant Tortoise". Gct.org. Archived from the original on 2008-04-30. Retrieved 2008-10-14.

- ↑ Rothschild 1902. Description of a new species of gigantic land tortoise from the Galápagos Islands. Novitates Zoologicae 9: 619.