Fulda Gap

RHQ – Regt Hq, 1/11 – 1st Squadron / 11th ACR, CAS – aviation, CSS – support

Soviet units are 8th Guards Army, US units are V Corps

G – Guards, MR – Motor Rifle, T – Tank, D – Division

The Fulda Gap is an area between the Hesse-Thuringian border (the former intra-German border) and Frankfurt am Main that contains two corridors of lowlands through which tanks might have driven in a surprise attack effort by the Soviets and their Warsaw Pact allies to gain crossing(s) of the Rhine River. Named for the town of Fulda, the Fulda Gap was strategically important during the Cold War. The Fulda Gap is roughly the route along which Napoleon chose to withdraw his armies after defeat at the Battle of Leipzig. Napoleon succeeded in defeating a Bavarian-Austrian army under Wrede in the Battle of Hanau not far from Frankfurt; from there he escaped home to France. The route was also used by the U.S. XII Corps during World War II to advance eastward in late March and early April 1945.

During the Cold War, the Fulda Gap was one of two obvious routes for a hypothetical Soviet tank attack on West Germany from Eastern Europe, especially East Germany; the other route was the North German Plain (a third, less likely, route was up through the Danube River valley in Austria). The concept of a major tank battle along the Fulda Gap was a predominant element of North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) war planning during the Cold War, and weapons such as nuclear tube and missile artillery, the nuclear recoilless gun/tactical launcher Davy Crockett, Special Atomic Demolition Munitions, the AH-64 Apache attack helicopter, and A-10 ground attack aircraft were developed with such an eventuality in mind.

Strategic location during the Cold War

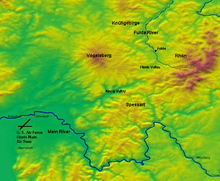

The northern route through the Gap passes south of the Knüllgebirge and then continues around the northern flank of the Vogelsberg Mountains; the narrower southern route passes through the Fliede and Kinzig Valleys, with the Vogelsberg to the north and the Rhön mountains and Spessart mountains to the south. Perhaps even more importantly, on emerging from the western exit of the Gap, one encounters gentle terrain from there to the river Rhine, which would have counted in favour of Soviet attempts to reach and cross the Rhine before NATO could prevent this (the intervening Main River would have been less of an obstacle).

The Fulda Gap route was less suitable for mechanized troop movement than was the North German Plain, but offered an avenue of advance direct to the heart of the U.S. military in West Germany, Frankfurt am Main, which as indicated in its name, is on the Main River, a tributary of the Rhine River. Frankfurt am Main was not only West Germany's financial heart, but also home to a large airfield (known as Rhein-Main Air Base and Frankfurt Airport) that was designated to receive U.S. reinforcements in the event of war.

Strategic responses to the geographic feature

Strategists on both sides of the Iron Curtain understood the Fulda Gap's importance, and accordingly allocated forces to defend and attack it. The defense of the Fulda Gap was a mission of the U.S. V Corps. The actual Inner German border in the Fulda Gap was guarded by reconnaissance forces, the identification and structure of which evolved over the years of the Cold War.

From June 1945 until July 1946, reconnaissance and security along the border between the U.S. and Soviet zones of occupation in Germany in the area north and south of Fulda was the mission of elements of the U.S. 3rd and 1st Infantry Divisions.[1] By July 1946, the 1st, 3rd, and 14th Constabulary Regiments (arranged from north to south) had assumed responsibility for inter-zonal border security in an area to include that which later become famous as the Cold War Fulda Gap.[2] The U.S. Constabulary as a headquarters was subsequently drawn down, but individual constabulary regiments were retitled armored cavalry regiments. This coincided with the 1951 upgrade of the U.S. Army's mostly administrative and occupation responsibilities in Germany to a combat army via the arrival of four U.S. combat divisions from CONUS. Thus, from 1951[3] until 1972, the 14th Armored Cavalry Regiment (ACR) patrolled the Fulda Gap.[4] After the return of the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment from Vietnam in 1972, the 11th ACR relieved the 14th ACR and took over the reconnaissance mission in the Fulda Gap until the end of the Cold War.

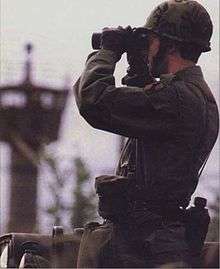

The mission of the armored cavalry (heavy, mechanized reconnaissance units equipped with tanks and other armored vehicles) in peacetime was to watch the East-West border for signs of pre-attack Soviet army movement. The armored cavalry's mission in war was to delay a Soviet attack until other units of the U.S. V Corps could be mobilized and deployed to defend the Fulda Gap.

The armored cavalry would have also served as a screening force in continuous visual contact with the Warsaw Pact forces, reporting on their composition and activities, and forcing advancing Warsaw Pact forces to deploy while the cavalry fought delaying actions. In order to defend the Fulda Gap and stop a Warsaw Pact advance (as opposed to conducting screening and delaying actions), U.S. V Corps planned to move two divisions (one armored and one mechanized) forward from bases in the Frankfurt and Bad Kreuznach areas.[5]

From 1947 until 1951, the 1st Infantry Division was the sole U.S. division in Germany, although the various Constabulary units taken together were equivalent in size to another division. U.S. Army forces in Germany were increased in 1951 as a result of President Truman's 10 Dec. 1950 declaration of a National Emergency as a result of the Korean War, with four divisions arriving from CONUS. This included the 4th Infantry Division, which was stationed in the Frankfurt area, and the 2nd Armored Division, which was located with its headquarters at Bad Kreuznach to the west of the Rhine River; both of those were the divisions assigned to the newly activated V Corps. Within six years, unit changes resulted in the arrival (May/June 1956) and stationing of the 3rd Armored Division (3rd AD) around Frankfurt, and the December 1957 arrival of the 8th Infantry Division (Mechanized) (8th ID) in the Bad Kreuznach area. The two replaced divisions returned to CONUS.

Cold War history from the 1950s of U.S. armor headquartered at Frankfurt (and therefore having an orientation that included the Fulda Gap):[6] 19th Armored Cav Group activated at Frankfurt on 2 January 1953; on 1 October 1953, the 19th Armd Cav Gp was redesignated as 19th Armor Group. On 1 July 1955, 19th Armor Group was replaced by 4th Armor Group. The Seventh Army troop list of 30 June 1956 [7] shows 4th Armor Group attached to V Corps, along with the U.S. divisions, 2d Armored Div, 3d Armored Div, and 10th Infantry Div. USAREUR Troop Lists dated 30 June 1958[8] show V Corps as containing 3rd Armored Div.(HQ Frankfurt), 8th Infantry Div. (HQ Bad Kreuznach), 4th Armor Group (HQ Frankfurt), & 3rd Infantry Div. (which was headquartered at Würzburg). After the 1963 ROAD reorganization, the 4th Armor Group was inactivated, and the 3rd Infantry Division headquartered at Würzburg was reassigned to VII Corps. The deployment of the 3rd Armored Division and the 8th Infantry Division to V Corps remained stable until the end of the Cold War. In practice, it was unknown how effective V Corps would have been in the event of war due to the vast numbers of tanks and infantry that the Soviets were able to field. In response to the quantitative superiority of the Soviet forces, the U.S. deployed Atomic Demolition Mines for many years in the Fulda Gap.[9]

From 1976 to 1984, the 4th Brigade of the 4th Infantry Division was garrisoned in Wiesbaden and also subordinated to U.S. V Corps.

For many years, V Corps' principal adversary was the Soviet 8th Guards Army, which was to be followed by additional armies (including the four armored divisions and one mechanized infantry division of the Soviet 1st Guards Tank Army), making the Fulda Gap a key entry route for the Soviet Bloc to western Europe in any hypothetical battle in Cold War Europe; both armies were well equipped and held high-priority for receiving new equipment.

Beginning in 1975, the Soviet Union's strategy for attacking Western Europe involved the use of Operational manoeuvre groups to outflank NATO defensive positions such as the Fulda Gap.[10]

From 1979 onwards, the first V Corps unit detailed to reinforce the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment in the Fulda Gap in the event of hostilities was the 8th Infantry Division's 1st Battalion, 68th Armored Regiment (1-68 Armor), stationed at Wildflecken to the south of the Gap. The mission of 1-68 Armor was to establish a defensive line across part of the Gap, providing a shield behind which other V Corps units could advance and defend. Also located in Wildflecken was the 108th Military Intelligence (MI) Btn, to which Delta Company Rangers was assigned - the Rangers' mission was to strike at the supply lines and command structures of any invading Soviet forces. 144th Ordnance Company was in charge of much of the ammunition slated for 8th Infantry Division and 3rd Armor Division, as well as operating ASP #3 in Wildflicken. 144th Ord. was also responsible for chemical and nuclear ammunition for the Fulda Gap sector, operating not only ASP #3 but multiple Forward Storage and Transportation Sites (FSTS). 547th Combat Engineer Battalion was tasked with destroying critical bridges to channel any Soviet advance, as well as provide critical engineering services to enable 1-68th Armor to engage Soviet forces.

In September 1980, the 533rd Military Intelligence (MI) Battalion was reactivated in Frankfurt and assigned to the 3rd Armored Division.[11] The 533rd MI Battalion deployed assets in the Fulda Gap to provide electronic warfare capability for the 3rd AD Commander. The missions of the MI battalion were to identify and target invading forces for artillery and air strikes as well as to intrude on enemy radio networks using radio jamming and deceptive communications by Defense Language Institute (DLI) trained Russian and German linguists. The 3rd Armored Division was also reinforced with an organic attack helicopter wing, and was the first military unit to deploy the attack helicopter Boeing AH-64 Apache in 1987.

With the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989, the reunification of Germany in 1990, and the subsequent withdrawal of Soviet forces, the Fulda Gap lost its strategic importance, but it remains a powerful symbol of the Cold War.

See also

- Observation Post Alpha—Cold War observation post that overlooked a part of the Fulda Gap, now the site of a Cold War memorial

- Seven Days to the River Rhine

Notes

- ↑ Border Ops, p. 9

- ↑ Border Ops, Map 3

- ↑ Border Ops, p. 60

- ↑ "History of the 14th ACR".

- ↑ A realistic description of U.S. concepts for the defence of the gap is contained in Bundeswehr University Munich, German & US generals discuss Fulda Gap defense, accessed December 2011

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ "The History of the Joint Chiefs of Staff--The Joint Chiefs of Staff and National Policy, Volume VI, 1955-56", by Kenneth W. Condit, (Washington: GPO, 1992)

- ↑ pages 104-5 of the Jan-Feb 2010 issue of Military Review, the journal of the U.S. Army's Combined Arms Center, Fort Leavenworth KS.

- ↑ "533rd MI Bn".

Further reading

- Faringdon, Hugh. Strategic Geography: NATO, the Warsaw Pact, and the Superpowers. Routledge (1989). ISBN 0-415-00980-4.

- Harper, John L. American Visions of Europe. Cambridge University Press (1994). ISBN 0-521-45483-2.

- Fulda Gap: The First Battle of the Next War. Designed by James F. Dunnigan, Simulations Publications, Inc., 1977. Board Game

- Vol.1, Encyclopedia of World Geography, R.W. McColl, Ed., 2005, Subj: "Fulda Gap" (by Ivan B. Welch). ISBN 978-0-8160-5786-3.

External links

- US Army Border Operations 1948–83 reproduced by the United States Army Center of Military History

- 14th Cavalry Association

- Squadrons, 14th CAV

- 11th CAV AOs

- 14th Cav at US Army Germany (History) site

- 11th Cav at US Army Germany (History) site

- From Fulda Gap button, one of 5 limited Fulda Gap pages at 1st Battalion 33rd Armor site

- Fulda Gap Big Picture from Decker's 1st Bn, 33rd Armor site

- 1st Bn 68th Armor at Wildflecken was a Fulda Gap screening force

- OPLAN 4102

- Fulda Gap Concerns in 1985

Coordinates: 50°37′N 9°25′E / 50.617°N 9.417°E