German Turfan expeditions

The German Turfan expeditions were conducted between 1902 and 1914. The four expeditions to Turfan in Xinjiang, China, were initiated by Albert Grünwedel, a former director at the Ethnological Museum of Berlin, and organized by Albert von Le Coq. Theodor Bartus, who was a technical member of the museum staff and was in charge of extricating paintings found during the expeditions from cave walls and ruins, accompanied all four expeditions. Both expedition leaders. Grünwedel and Le Coq, returned to Berlin with thousands of paintings and other art objects, as well as more than 40,000 fragments of text. In 1902, the first research team financed largely by Friedrich Krupp, the arms manufacturer, left for Turfan and returned a year later with 46 crates full of treasures. Kaiser Wilhelm II was enthusiastic and helped finance the second expedition along with Krupp.[1] The third was financed by means of the Ministry of Culture. The fourth expedition under Le Coq was dogged by many difficulties and was finally cut short by the outbreak of World War I in 1914.[2]

Many important finds were made, especially on the second expedition, at a number of sites along the ancient northern route around the Taklamakan desert. They discovered important documents and works of art (including a magnificent wall-painting of Manes, the founder of Manichaeism) and the remains of a Nestorian (Christian) church near ancient Khocho (Qara-khoja or Gaochang), a ruined ancient city, built of mud, 30 km (19 mi) east of Turfan.[3]

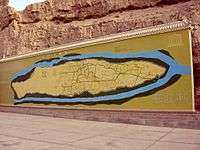

Geography

Turfan (also Uigur Turpan, Chin. Tulufan) is in Xinjiang (Chinese Turkestan) on the northern Silk Road. It has an area of 170 km2 (66 sq mi) between 42° and 43° north latitude and between 88° and 90° east longitude in a depression 154 m (505 ft) below sea level. This is the archaeological site to which expeditions were mounted by Germans to explore and collect precious art objects and texts written in many languages and scripts.[4]

History

International attention was first drawn to Turfan by Sven Hedin (1865-1952), to European and Japanese archaeologists, as a potential and promising site in Central Asia for field explorations for archaeological finds. He could follow up the work in later years during his last expeditions between 1928 and 1935. His collections of that period are in the Stockholm Ethnographical Museum. After his first suggestion to the archeologist about the archaeological richness of the Turfan site, many Russian expeditions were mounted from September 27 to November 21, 1879 right up to 1914–1915, Finnish expeditions from 1906 to 1908, by Japan between July 1908 and June 1914, and also other explorers from Great Britain, France and America; and from 1928 Chinese archaeological campaigns continued the work of the foreign expeditions. German expeditions from 1902 and 1914 not only to Turfan but also other sites such as Kucha, Qarashahr and Tumshuq [Tumšuq] were most fruitful.[4] Toward the end of the nineteenth century, Germans were impressed by the discoveries and finds reported by Europeans traveling through the Silk Roads and the exposition made at the twelfth international Congress of Orientalists in Rome in the year 1899 prompted them to launch their own expeditions to the area. The finds of the four expeditions (packed and carted to Germany initially) were murals, other artefacts and about 40,000 pieces of texts.[5] The four German expeditions covered Turfan but also Kucha, Qarashahr and Tumshuq [Tumšuq]. The expeditions were:[4][5]

- First Expedition: November 1902 – March 1903 led by Prof. Grünwedel along with the Orientalist scholar, Georg Huth,[6] and Bartus, as fellow participants;

- Second Expedition: November 1904 – August 1905 led by Le Coq along with Bartus;

- Third Expedition: united with the second Expedition, from December 1905 to April 1907 led by Grünwedel and Le Coq, H. Pohrt and Bartus as fellow participants;

- Fourth Expedition: June 1913 – February 1914 led by Le Coq along with Bartus as a participant.

First Expedition

The financing for the expedition involved 36,000 Marks which was provided by the Königliche Museum für Völkerkunde in Berlin, by James Simon (benefactor of museums), Krupp house, the Prussian Government and an “Ethnologisches Hilfskomitee.”[4] The first Expedition from December, 1902 to April 1903, led by Prof. A. Grünwedel along with Dr. G. Huth and Theodor Bartus, followed the route from Yining to Urumqito Turfan Oasis when paintings, statues and manuscripts were found and carted in 46 crates,[5] and the zoological objects in plus 13 crates. The detailed account of the expedition was published in Grünwedel's book titled "Bericht über archäologische Arbeiten in Idikutschari und Umgebung im Winter 1902-1903", Abhandlungen der Königlich Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, I. Kl., XXIV. Bd., München 1906.[4]

Second Expedition

Impressed with the sensational accomplishments of the first expedition, Emperor Wilhelm II donated 32,000 Marks from his private purse (the “Allerhöchste Dispositionsfonds”) which was supplemented by 10,000 Marks from other donors.[4] On account of Wilhelm II's donation as King of Prussia, this expedition was also named the "First Royal Prussian Turfan expedition". Since Grünwedel who was very enthusiastic about leading the second expedition also could not make it due to ill health, instead Dr. Albert von Le Coq (1860-1930) of the “Hilfsarbeiter bei dem Königlichen Museum für Völkerkunde”, headed the second expedition,[4] along with Theodor Bartus as his associates, followed the route from Ürümqi to Turfan Oasis (from November 1904 to August 1905). The third Expedition merged with this expedition (from Aug. 1905) and the finds covered mostly paintings (Bezeklik) but very few texts. It was carted to Berlin in 105 crates.[5]

Third Expedition

The Third Expedition was also funded by the state. It was undertaken from December 1905 to April 1907 (combined with the second expedition). In the middle of 1906 Le Coq had to return home due to illness. Grünwedel and Bartus continued the work and covered the oases to the west of Turfan, including Kïzïl and its widespread complexes of Buddhist caves. The route followed was initially from Kashgarto Tumshuk and then from Kizilto Kucha to Kumtura and further along Shorchuk—Turfan Oasis—Ürümqi—Hami—Toyuk and back. The collections packed in 118 crates were paintings of grottoes from temples and Buddhist texts. Reports of the second and third expeditions were published as Gründwedel's Altbuddhistische Kultstätten in Chinesisch-Turkistan (1912) and Le Coq's book of Auf Hellas Spuren in Ostturkistan (1926).[5]

Fourth Expedition

The Fourth Expedition was also funded by the state (60,000 Marks given by the emperor and by private benefactors). It was again led by Le Coq along with Theodor Bartus. They followed the route from Kashgar to Kucha, then Kizil to Kirish, followed by Simsim to Kumtura and then from Tumshuk to Kashgar to Shorchuk to Turfan Oasis and finally from Ürümqi—Hami—Toyuk —Shorchuk —Turfan and returned from Ürümqi and completed the expedition shortly before the outbreak of the First World War. Finds included paintings and texts in Sakan and Sanskrit. The finds packed in 156 crates, was the largest collection in a single expedition. Le Coq published his report of his expedition in Von Land und Leuten in Ostturkistan, in 1928.[5]

Fate of the collections

The collections from the German expeditions were initially kept at the Indian Department of the Ethnological Museum of Berlin (Ethnologisches Museum Berlin), then shifted in 1963 to the Museum of Indian Art (Museum für Indische Kunst) in Dahlem, Berlin and finally combined into a single location at the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities (Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften, BBAW), since 1992. During World War II, the Ethnological Museum was bombed seven times in Allied bombing raids, destroying the larger wall murals which had been cemented into place and could not be moved; 28 of the finest paintings were totally destroyed. Smaller pieces were hidden in bunkers and coal mines at the outbreak of war and survived the bombings. When the Russians arrived in 1945 they looted at least 10 crates of treasures that they discovered in a bunker under the Berlin Zoo which have not been seen since. The remaining items have been collected together and are housed in a new museum in Dahlem, a suburb of Berlin.[10]

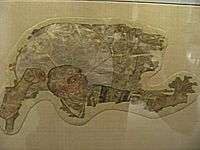

Gallery

-

A wall painting

-

Turfan Buddhas

Footnotes

- ↑ Hopkirk (1980), p. 114.

- ↑ Hopkirk (1980), p. 207.

- ↑ Hopkirk (1980), pp. 118, 122–123.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Turfan Expeditions". Iranica Online. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "German Collections". International Dunhuang Project. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ↑ Agnew, Neville (3 August 2010). Conservation of Ancient Sites on the Silk Road. Getty Publications. pp. 98–. ISBN 978-1-60606-013-1. Retrieved 6 November 2012.

- ↑ von Le Coq, Albert. (1913). Chotscho: Facsimile-Wiedergaben der Wichtigeren Funde der Ersten Königlich Preussischen Expedition nach Turfan in Ost-Turkistan. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer (Ernst Vohsen), im Auftrage der Gernalverwaltung der Königlichen Museen aus Mitteln des Baessler-Institutes, Tafel 19. (Accessed 3 September 2016).

- ↑ Gasparini, Mariachiara. "A Mathematic Expression of Art: Sino-Iranian and Uighur Textile Interactions and the Turfan Textile Collection in Berlin," in Rudolf G. Wagner and Monica Juneja (eds), Transcultural Studies, Ruprecht-Karls Universität Heidelberg, No 1 (2014), pp 134-163. ISSN 2191-6411. See also endnote #32. (Accessed 3 September 2016.)

- ↑ Hansen, Valerie (2012), The Silk Road: A New History, Oxford University Press, p. 98, ISBN 978-0-19-993921-3.

- ↑ From the Introduction by Peter Hopkirk in the 1985 edition of Von Le Coq's Buried Treasures of Chinese Turkestan, p. ix-x.

References

- Franz, H. G.: Kunst und Kultur entlang der Seidenstraße. Graz, 1986. (German language)

- Gumbrecht, Cordula: Acta Turfanica: die deutschen Turfan-Expeditionen gesehen in den Archiven von Urumchi und Berlin. Berlin, 2002. (German language)

- Grünwedel, A.: Altbuddhistische Kultstätten in Chinesisch Turkistan, Bericht über archäologische Arbeiten von 1906 bis 1907 bei Kucha, Qaraæahr und in der Oase Turfan. Berlin, 1912. (German language)

- Härtel, H. & Yaldiz, M.: Die Seidenstraße: Malereien und Plastiken aus buddhistischen Höhlentempeln. Aus der Sammlung des Museums für Indische Kunst Berlin. Berlin: Reimer, 1987 (German language)

- Hopkirk, Peter (1980), Foreign Devils on the Silk Road: The Search for the Lost Cities and Treasures of Chinese Central Asia. Oxford University Press, John Murray, Oxford; Paperback. Reprinted 1985, 1986, 1988, 1991. ISBN 0-19-281487-7.

- Le Coq, A. v.. Buried Treasures of Chinese Turkestan. George Allen & Unwin Ltd. 1928. Paperback with introduction, Hong Kong, Oxford University Press, 1985. ISBN 0-19-583878-5.

- Le Coq, A. v.: Auf Hellas Spuren in Ostturkistan. Berichte und Abhandlungen der II. und III. Deutschen Turfan-Expedition. Leipzig, 1926. (German language)

- Yaldiz, M.: Archäologie und Kunstgeschichte Chinesisch-Zentralasiens (Xinjiang). Leiden, 1987. (German language)

- Zaturpanskij, Choros: "Reisewege und Ergebnisse der deutschen Turfanexpeditionen", Orientalisches Archiv 3, 1912, pp. 116–127. (German language)