Giordano Vitale

Giordano Vitale or Vitale Giordano (October 15, 1633 – November 3, 1711) was an Italian mathematician. He is best known for his theorem on Saccheri quadrilaterals. He may also be referred to as Vitale Giordani, Vitale Giordano da Bitonto, and simply Giordano.

Life

Giordano was born in Bitonto, in southeastern Italy, probably on October 15, 1633. As an adolescent he left (or was forced to leave) his city and, after an adventurous youth (that included killing his brother-in-law for calling him lazy) he became a soldier in the Pontifical army. During these adventures he read his first book of mathematics, the Aritmetica prattica by Clavius. At twenty-eight, living in Rome, he decided to devote himself to mathematics. The most important book he studied was Euclid's Elements in the Italian translation by Commandino.

In Rome he made acquaintance with the renowned mathematicians Giovanni Borelli and Michelangelo Ricci, who became his friends. He was employed for a year as a mathematician by ex-Queen Christina of Sweden during her final stay in Rome. In 1667, a year after its foundation by Louis XIV, he became a lecturer in mathematics at the French Academy in Rome, and in 1685 he gained the chair of mathematics at the prestigious Sapienza University of Rome. Friend of Vincenzo Viviani, Giordano met Leibniz in Rome when Leibniz stayed there during his journey through Italy in the years 1689–90. He gave Leibniz a copy of the second edition of his book Euclide restituto. Giordano died on November 3, 1711, and was buried in the San Lorenzo in Damaso basilica church in Rome.

Work

Giordano is most noted nowadays for a theorem on Saccheri quadrilaterals that he proved in his 1668 book Euclide restituo (named after Borelli's Euclides Restitutus of 1658).

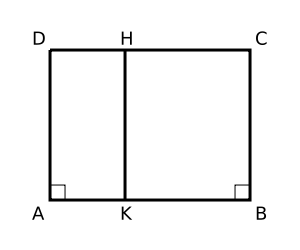

In examining Borelli's proof of the parallel postulate, Giordano noted that it depended upon the assumption that a line everywhere equidistant from a straight line is itself straight. This in turn is due to Clavius, whose proof of the assumption in his 1574 Commentary on Euclid is faulty.[1][2] So using a figure he found in Clavius, now called a Saccheri quadrilateral, Giordano tried to come up with his own proof of the assumption, in the course of which he proved:

- If ABCD is a Saccheri quadrilateral (angles A and B right angles, sides AD and BC equal) and HK is any perpendicular from DC to AB, then

- (i) the angles at C and D are equal, and

- (ii) if in addition HK is equal to AD, then angles C and D are right angles, and DC is equidistant from AB.

The interesting bit is the second part (the first part had already been proved by Omar Khayyám in the 11th century), which can be restated as:

- If 3 points of a line CD are equidistant from a line AB then all points are equidistant.

Which is the first real advance in understanding the parallel postulate in 600 years.[3][4]

Publications

Giordano's published work includes:

- Lexicon mathematicum astronomicum geometricum (1st edition 1668, Paris. 2nd edition with additions 1690, Rome)

- Euclide restituto, ovvero gli antichi elementi geometrici ristaurati e facilitati da Vitale Giordano da Bitonto. Libri XV. ("Euclid Restored, or the ancient geometric elements rebuilt and facilitated by Giordano Vitale, 15 Books"), (1st edition 1680, Rome. 2nd edition with additions 1686, Rome)

- Fundamentum doctrinae motus grauium et comparatio momentorum grauis in planis seiunctis ad grauitationes (1689, Rome)

Notes

- ↑ [T. L. Heath (1908), "The Thirteen Books of Euclid's Elements, Vol. 1", p.194, University Press, Cambridge]

- ↑ [George Bruce Halsted (1920), translator's preface to Saccheri's "Euclides Vindicatus", p.ix, The Open Court Publishing Company, Chicago]

- ↑ [Roberto Bonola (1912), "Non-Euclidean Geometry", p.15, The Open Court Publishing Company, Chicago]

- ↑ [George Edward Martin (1998), "The Foundations of Geometry and the Non-Euclidean Plane", p.272, Springer]

References

- M. Teresa Borgato, manoscritti non pubblicati di Vitale Giordano, corrispondente di Leibniz.

- Leibniz Tradition und Aktualitat V. Internationaler Leibniz-Kongress, unter der Schirmherrschaft des Niedersachsischen Ministerprasidenten Dr. Ernst Albrecht, Vortrage Hannover 14–19 November 1988.

- Francisco Tampoia, Vitale Giordano, Un matematico bitontino nella Roma barocca, Arming Publisher Rome 2005.

| Italian Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

External links

- Roberto Bonola (1912) Non-Euclidean Geometry, Open Court, Chicago. English translation by H. S. Carslaw.

-

Media related to Giordano Vitale (mathematician) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Giordano Vitale (mathematician) at Wikimedia Commons