Giosue Gallucci

| Giosuè Gallucci | |

|---|---|

|

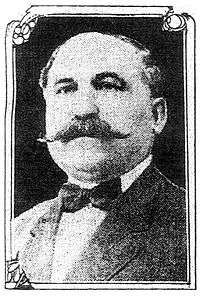

Giosuè Gallucci, the King of Little Italy | |

| Born |

December 10, 1865 Naples, Italy |

| Died |

May 21, 1915 (aged 49) New York City |

| Cause of death | Shot through the stomach and neck |

| Other names | Luccariello; King of Little Italy |

| Known for | Running numbers rackets in Little Italy |

| Allegiance | Camorra in New York |

Giosuè Gallucci (Italian pronunciation: [dʒozuˈɛ ɡɡalˈluttʃi]; December 10, 1865 – May 21, 1915), also known as Luccariello,[1] was an old-style crime boss of Italian Harlem in New York City affiliated with the Camorra. He dominated the area from 1910–1915 and was also known as the undisputed King of Little Italy or The Mayor of Little Italy, partly due to his political connections.[2][3] He held strict control over the policy game (numbers racket), employing Neapolitan and Sicilian street gangs as his enforcers.

Born in Naples, Italy, Gallucci became one of the most powerful Italians politically in the city. With his ability to mobilize the vote in Harlem and register immigrants, he delivered a significant number of ballots. He gained virtual immunity from law enforcement through mastery of New York City politics at the Democratic political machine in Tammany Hall that ruled Manhattan virtually unopposed. Despite his power and political clout, Gallucci was not immune from Black Hand extortion and his rule was challenged frequently. In 1915 he was killed by a rival gang. The fight over the lucrative numbers rackets left behind by Gallucci is known as the Mafia-Camorra War.

From Naples to New York

Giosuè Gallucci was born in Naples, Italy, in 1865 to Luca Gallucci and Antonia Cavallo.[4] He left Italy in July 1886 at the age of 20.[5] In 1891 he moved to New York City, arriving on March 11, 1892, on the SS Werkendam from Rotterdam, the Netherlands.[6][7][8] According to an Italian police report he had left Italy on July 24, 1896.[9][10] An 1862 report from the police in Naples identified a Giuseppe and Giosuè Gallucci as camorristi − Italian for a members of the Camorra −, but it is unknown if these were relatives.[11] Rumour had it that Gallucci had killed a man just before coming to New York, but he always denied this.[12]

In April 1898, he was arrested in New York in connection with the murder of Josephine Inselma, who was portrayed as Gallucci's lover by the police. The apprehension took place while he was operating a fruit wagon in the neighbourhood and he was described as "a young grocer and expressman, with a store at 172 Mott street". Gallucci said he had no reason to kill the woman and provided an alibi.[13][14] The Grand Jury dismissed the charges. New York City Police Department detective Joe Petrosino, who was in charge of the investigation, urged his superiors to inquire for more information in Italy. The police prefect of Naples responded that Giosuè Gallucci was "a dangerous criminal, belonging to the category of blackmailers, and for his very bad character was put under special police surveillance and confined to prison. He was charged several times with theft and association with delinquents, and was condemned nine times for theft, outrages, blackmail, lesion, and transgressions of the special police surveillance."[9][10][15]

The criminal background of his brothers Gennaro, Vincenzo and Francesco in Italy was even more extensive. Vincenzo Gallucci was described as a blackmailer who spent two terms in prison and was condemned sixteen times for assault, attempted murder and other crimes. Francesco Gallucci was condemned six times for attempted murder and theft and for assaulting policemen.[9] His brother Vincenzo was murdered in New York City on November 20, 1898, supposedly on orders from an Italian "secret society similar to the Mafia" (probably the Neapolitan Camorra).[16] Francesco D'Angelo and Luigi LaRosa were accused of the killing; both pleaded guilty to manslaughter and were sentenced to 20 years and 15 years in prison, respectively.[16]

According to Petrosino, the Galluccis were only three of the more than 1,000 Italian "rascals" from Naples and Sicily who had made New York City their home. They did not attract much attention because, "as a class, they rob their own people, and the Italian scheme of 'fix it myself' interferes to throw the police off the scent."[15] Since they had been in the country for more than a year, the Galluccis could not be deported.[15]

King of Little Italy

Gallucci eventually built various businesses in East Harlem; first in Mulberry Street and later in a three story brick house with a bakery and an attached stable at 318 East 109th Street.[3] He would become the undisputed boss of Little Italy following the imprisonment of the Sicilian-American Black Hand leader Ignazio Saietta on counterfeit charges in 1909.[2] He owned many tenements in the area and controlled the coal and ice business, cobbler shops, the olive oil business and the lottery in the Italian neighbourhoods. He was one of the biggest moneylenders and held strict control over the policy game (numbers racket), employing Neapolitan and Sicilian street gangs as his enforcers; nobody ran numbers without paying tribute to Gallucci.[2][3][6]

Gallucci ran what was supposed to be the New York office of the Royal Italian Lottery, which in fact was a front for his own policy game selling thousands of tickets every month throughout Harlem.[6] He ran the lottery from the basement of his home and he had agents in many cities with Italian communities. Every month there was a "grand drawing." There was only one prize, USD 1,000, but the one who won the prize was almost certainly robbed of the money when it was paid.[17]

Newspapers at the time wrote about him as a legitimate businessman; the personification of a successful immigrant. He was an imposing man, "a big fellow with a pleasant face and a hearty laugh."[18] While he paraded through Harlem swinging a loaded cane, he was always immaculately dressed in tailored suits with a magnificently waxed moustache, an expensive USD 2,000 diamond ring and USD 3,000 diamond shirt studs.[6][18] Gallucci denied the allegations. "My enemies say that I am the head of the 'Black Hand' business, that I run the blackmail bomb business and that I own all the lotteries," Gallucci complained a week before he was killed. "They are wrong. I own bakeries, ice and wood shops, shoe shining and repair shops and similar places, but I am not king of the 'Black Hand'."[18]

Political influence

He gained virtual immunity from law enforcement through mastery of New York City politics at the Democratic political machine in Tammany Hall that ruled Manhattan virtually unopposed.[2] The political patronage of Tammany Hall controlled the city's police and bureaucracy that handed out the construction contracts and licenses. With his ability to mobilize the vote in Harlem and register immigrants, he delivered a significant number of ballots. According to the New York Herald, he was "certainly the most powerful Italian politically in the city, and during campaigns was exceptionally active." His political connections allowed for "a certain measure of immunity from police interference."[2][6][18]

According to Salvatore Cotillo, the first Italian-born Justice of the New York Supreme Court who grew up in Italian Harlem, "to Gallucci all people were either hirelings or payers of tribute. It was a matter of concern in the neighbourhood if you were looked down upon by Gallucci."[6][19] When Gallucci was arrested for carrying concealed weapons, Cotillo was asked to testify as a character witness on his behalf, but refused. In doing so, the Neapolitan-born Cotillo distanced himself from the local underworld that tried to offer him their "services".[19][20]

"I have been accused of being interested in horse thieves, blackmailing, extortion from shop keepers, bomb explosions, kidnapping of children and other crimes, including murder," Gallucci allegedly told a reporter from the New York Herald who claimed to know him. "My enemies are lying. They are jealous of my prosperity. I am blamed for every criminal deed which takes place here, but it is not the truth," he told the Herald reporter. "Many of the murders down here are the results of quarrels among the blackmailers themselves. They gamble, which leads to fighting, and they dispute the division of spoils. If a leader thinks another is trying to become boss, that man is marked for death."[21]

Killing his brother?

His elder brother, Gennaro Gallucci (born 1857), was shot dead on November 14, 1909, in the back room of the family bakery.[22] The assassin entered the bakery and yelled for Gennaro. When he appeared, he was shot and killed immediately.[23] His activities as a collector of protection payments had caught the attention of the authorities earlier, and he had to leave New York City for a while. Gennaro had arrived in New York from Italy in December 1908, having escaped from prison after serving 23 years of a life sentence for murdering two men. He lived on East 109th Street with his brother, Giosuè, and sister-in-law, Assunta.[5][23][24] Soon after his arrival, the police began receiving complaints about extortion practices, but when the plaintiffs were told that they had to confront him in court, they dropped the charges.[23]

When he returned in the late summer of 1909, the New York Police captured him on September 20, 1909, while carrying concealed weapons. Immigration officials began efforts to deport him to Italy.[5][25] However, the courts were unaware of his full criminal background and released him with a suspended sentence. The police believed his killing two months later may have been connected to Gennaro's blackmailing activities. The bakery of the Galluccis had been attacked only a few months before when bullets smashed through the window. In letters that were sent to the police, some informants claimed that Giosuè Gallucci had been responsible for the killing of his brother.[5]

In contrast, Gallucci blamed Aniello Prisco – nicknamed "Zopo the Gimp", a notorious lame and feared gangster from Harlem – for the death of his brother. For the next two years there would be frequent clashes and occasional killings between the rivals.[26] Prisco was the head of a Black Hand gang who accused Gallucci of trespassing on his territory.[18]

Fighting over underworld control

A police report from 1917, based on the testimony of the gangster and informer Ralph Daniello, described Gallucci's position around 1912: "At that time Gallucci controlled different gambling games and he would get a percentage on the sale of stolen horses and peddled artichokes. If anybody would not pay this percentage he would either be assaulted, receive blackmail letters or be killed." The report continued to explain that a Sicilian faction, including three Morello brothers and the brothers Fortunato and Tomasso Lomonte, cousins of Giuseppe Morello,[27] were "working in conjunction with this Galucci, who at all times had been recognized as king." [1]

Despite his power and political clout, Gallucci was not immune from Black Hand extortion. He frequently received Black Hand threats, was often shot at, and had been wounded many times.[2] In 1911, the gang of Neapolitan "black handers" run by Prisco gunned down several members of Gallucci's entourage because he refused to make "protection" payments. On December 15, 1912, he retaliated when Prisco was lured into a trap in Gallucci's bakery shop and shot by Gallucci's nephew and body guard John Russomano.[27][28][29] Russomano was acquitted of the murder because he fired in self-defence.

Gallucci was not only challenged by rival gangsters, but the authorities also closed in responding to the spate of killings, bombings and black-mailings. In July 1913, he was among the more than 40 arrests made around Mulberry Bend and in upper Harlem to suppress illegal gambling known as the policy game; a charge led by Assistant District Attorney Deacon Murphy and Deputy Police Commissioner George S. Dougherty.[3][27][30] At the time, the police described him as "the leader of the Italian criminals in Harlem" and that "his consent was necessary before anything out of the way could be done in Harlem's Little Italy." Speculation about the reason behind the arrests was that it could have been an attempt to smash Gallucci's vice ring.[31] He was well known for being involved with prostitution rackets and was also known as the King of the White Slavers in the press.[3] He was charged with carrying a concealed weapon, a transgression of the Sullivan Act, but was released on a USD 10,000 bail. The case failed to reach court, a fact that many attributed to his political connections.[3][18]

According to newspaper reports, no one could operate a lottery, a poolroom or a saloon without Gallucci's permission, although Gallucci denied this.[12] Nevertheless, firm control or not, he was involved in violent disputes with rival gangs. The Neapolitan Del Gaudio brothers, who had connections with the Brooklyn based Navy Street gang, were involved in illegal gambling in East Harlem, but Gallucci allegedly denied them permission to operate a lottery. Nicolo Del Gaudio, brother to Gaetano, owned a barber shop on East 104th Street, which had been proposed as a meeting place between Prisco and Gallucci. Nicolo Del Gaudio had tried to kill Gallucci, but had failed. He fled from Italian Harlem, but returned in October 1914 and was subsequently killed. The killing was attributed to Gallucci, but no charges were ever made.[7][27]

Assassination

Gallucci's prestige began to wither as the gang war with the remains of Prisco's old outfit lingered on and he was scrambling to maintain control. Only a week before he was killed, Gallucci had decided not to employ bodyguards anymore, after the latest in a series had been shot and killed. Being a bodyguard for Gallucci was considered an unsafe way to make a living, as ten of them had been killed.[2] The year before, Gallucci had been wounded and two of his bodyguards had been killed when he tried to make a collection in a shop on First Avenue.[18] Meanwhile, the Morellos had fallen out with Gallucci and had formed an alliance with the Camorra gangs from Brooklyn.[1]

Gallucci foresaw his execution, saying "I know they will get me."[2][18] Rival lotteries were springing up right under his nose. He and his 18-year-old son Luca were shot on May 17, 1915, in a coffee shop on East 109th Street in Italian Harlem that Gallucci had recently purchased for his son. He was shot through the stomach and neck. In an effort to defend him, his son also was shot through the stomach.[33][34] Fifteen men, mostly friends of Gallucci's, were in the coffee shop and some returned fire.[3] The five or six shooters got away, leaping into a waiting escape car around the corner on First Avenue.[18]

His son died the next day in Bellevue Hospital.[35] The funeral was attended by 5,000 people and accompanied by 800 carriages, 22 carriages for flowers alone.[3][36] The funeral for Gallucci's son was the biggest Harlem had ever experienced up to that time, and possibly was the biggest one ever for a member of the underworld. According to reports, the last carriages were leaving the church in Harlem when the hearse after had already arrived at the cemetery in Queens.[36]

Giosuè Gallucci refused to talk to the police, saying he would settle the case himself, but he died at Bellevue Hospital three days later, on May 21, of a bullet wound in the abdomen.[35] Like most underworld killings, Gallucci's murder remained unsolved. The alleged killers were Gallucci's former bodyguards Joe 'Chuck' Nazzarro and Tony Romano, with the help of Andrea Ricci, of the rival Navy Street gang from Brooklyn.[3] The money for the hit was probably provided by Coney Island Camorra boss Pellegrino Morano, in an effort to take over Gallucci's rackets.[1][7] Nazzaro had a grudge against Gallucci, who had not paid his bail when Nazzaro, Gallucci and his nephew, John Russomano, were arrested for carrying concealed weapons.[37][38] He had to spend 10 months in prison. A few weeks before the fatal shooting of Gallucci, Nazzaro had been released. Gallucci was asked to buy USD 300 worth of tickets for a racket for Nazarro's benefit, but Gallucci flatly refused. A week later, he and his son were shot.[38]

Burial and legacy

His funeral was closely guarded by police, who feared further gang fights. Several thousand people filed through Gallucci's apartment to view the remains.[39] Some 10,000 persons blocked East 109th Street to witness Gallucci's last journey, including some 250 police detectives, present due to a rumour that the widow of Gallucci had also been targeted for assassination.[18][40] The 150 carriages that were expected for the burial procession were reduced to 54 because of fear for hostile demonstrations. The procession was preceded by a 23-strong musical band.[36][39] The funeral service was held at the Church of Our Lady of Mount Carmel, located at 113th Street and First Avenue. He was buried in Calvary Cemetery.[39]

According to the New York Herald, at the time of his death, he held USD 350,000 in real estate and was considered to be a millionaire.[2][18] In reality, Gallucci left behind only USD 3,402 in cash and the property at 318 East 109 Street, which was subsequently rented out.[7] The lucrative numbers rackets left behind by Gallucci were now free for the taking, and they soon passed over to the Sicilian Morello gang,[3][17] while the Camorra gangs took over control in Brooklyn.[1] The subsequent fight over those rackets with the Camorra gangs from Brooklyn is known as the Mafia-Camorra War, and would eventually elevate Vincenzo and Ciro Terranova to "boss" status in the Harlem underworld.[3]

In The Godfather ?

According to some, Don Fanucci, a fictional character appearing in the Mario Puzo novel The Godfather and the film The Godfather Part II, seems to be based on Giosuè Gallucci, "the mobster who strolled in East Harlem in expensively tailored suits extorting protection money from everyone in New York's Italian quarter."[41]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gangs Took Life for Small Cause, The New York Sun, December 26, 1917, p.8. His name is also often spelled as Galucci.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Nelli, The Business of Crime, pp. 129-31

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Giosuè Gallucci, GangRule.com (Retrieved June 11, 2016)

- ↑ Gennaro Gallucci, GangRule.com (Retrieved June 11, 2016) According to other but older sources he came from Palermo, Sicily, see: Nelli, The Business of Crime, pp. 129-31

- 1 2 3 4 Gennaro Gallucci, GangRule.com (Retrieved June 11, 2016)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Dash, The First Family, pp. 239-43

- 1 2 3 4 Critchley, The Origin of Organized Crime in America, pp. 109-11

- ↑ Passenger Giosuè Gallucci, Ellis Island/Port of New York Records. Other passenger records show that a Giosuè Gallucci arrived on Ellis Island on August 8, 1899, from Bremen (Germany), identified as a 35-year-old male Italian citizen from Naples. Another Giosuè Gallucci arrived on October 4, 1906, from Naples with the Prinzess Irene, identified as a 42-year-old U.S. citizen, travelling with his niece Emma who would stay at her uncle's address at 339 East 109th Street. Passenger record Ellis Island (registration required)

- 1 2 3 Criminals Sent From Italy, New York Herald, June 21, 1898, p.10

- 1 2 Cast-Off Criminals; How those of Europe find an asylum in America, Kansas City Journal, July 10, 1898, p.18

- ↑ Monnier, La camorra: notizie storiche raccolte e documentate, Appendix XV: Giuseppe e Giosuè Gallucci (Retrieved June 11, 2016)

- 1 2 Swear Revenge As Italy Boss Dies, New York Herald, May 22, 1915, p.8

- ↑ Dead With Her Throat Cut, The New York Times, April 19, 1898, p.12

- ↑ Woman Killed, No Clew To Slayer, New York Herald, April 19, 1898, p.10

- 1 2 3 Nest of Italian Thugs, New York Sun, June 21, 1898, p.5

- 1 2 Grades in Murder, New York Sun, April 29, 1899, p.8

- 1 2 Amazing Tale of 23 Italian Gang Killings, New York Herald, November 30, 1917, p.2

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Million Dollar Leader and Son Shot by Assassins Who Have Slain 10 of His Aids, New York Herald, May 18, 1915, p.7

- 1 2 Ferber, A New American, p. 20

- ↑ Shaffer & Shaffer, Lawyers as Assimilators and Preservers.

- ↑ Harlem's "Murder Stable Feud" Counts 21st Victim, New York Herald, January 7, 1917, p.2

- ↑ Italian "Bad Man" Strangely Slain, The New York Times, November 15, 1909

- 1 2 3 Downey, Gangster City, pp. 83-84

- ↑ Slayer in Hiding Is Shot Down by Unknown Avenger, New York Herald, November 15, 1909, p.1

- ↑ Caught After Year's Chase, The New York Times, September 21, 1909

- ↑ Black Hand Slays Victim Who Doffs His Chinese Armor, New York Herald, April 10, 1913, p.1

- 1 2 3 4 The Struggle for Control, GangRule.com (Retrieved June 11, 2016)

- ↑ Kills A Gangster To Save His Uncle, The New York Times, December 17, 1912

- ↑ New York Letter, The Day Book, January 2, 1913

- ↑ Raid Italian Policy Shops; Police Dragnet Brings 35 Prisoners to Headquarters, The New York Times, July 27, 1913

- ↑ Expect To Break Up Italian Vice Trust, The New York Sun, August 1, 1913, p.5

- ↑ Generossi Nazzaro, GangRule.com (Retrieved June 11, 2016)

- ↑ Father and Son Shot, The New York Times, May 18, 1915

- ↑ Two Shot Down In Harlem Feud, The New York Tribune, May 18, 1915, p.1

- 1 2 'King of Little Italy' Dies, The New York Times, May 22, 1915

- 1 2 3 Downey, Gangster City, pp. 85-86

- ↑ Critchley, The Origin of Organized Crime in America, p. 116

- 1 2 Downey, Gangster City, p. 86

- 1 2 3 Gallucci Funeral Guarded, The New York Times, May 25, 1915

- ↑ Guard Widow At Gallucci Funeral, The New York Herald, May 25, 1915, p.8

- ↑ Coppola's Godfather, Puzo's Godfather, italkyoubored blog, August 31, 2013 (Retrieved June 11, 2016)

Sources

- Critchley, David (2009). The Origin of Organized Crime in America: The New York City Mafia, 1891-1931, New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-99030-0

- Dash, Mike (2009). The First Family: Terror, Extortion, Revenge, Murder, and the Birth of the American Mafia, New York: Random House, ISBN 978-1-4000-6722-0

- Downey, Patrick (2004). Gangster City: The History of the New York Underworld, 1900-1935, Fort Lee (NJ): Barricade Books, ISBN 978-1-56980-361-5

- Ferber, Nat Joseph (1938). A New American. From the Life Story of Salvatore A. Cotillo, Supreme Court Justice, State of New York, New York: Farrar & Rinehart

- Gangrule.com, a database of historic events, family histories and photographs based on research from primary sources including police, federal, court, immigration, business, and prison records, based on Critchley's The Origin of Organized Crime in America: The New York City Mafia, 1891-1931.

- Monnier, Marco (1863). La camorra: notizie storiche raccolte e documentate, Firenze: G. Barbera (Original version)

- Nelli, Humbert S. (1981). The Business of Crime. Italians and Syndicate Crime in the United States, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press ISBN 0-226-57132-7 (Originally published in 1976)

- Shaffer, Thomas L. and Shaffer, Mary M., (1988). Lawyers as Assimilators and Preservers, Scholarly Works Notre Dame Law School, Paper 146