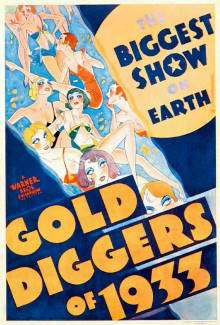

Gold Diggers of 1933

| Gold Diggers of 1933 | |

|---|---|

theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by |

Mervyn LeRoy Busby Berkeley (musical sequences) |

| Produced by |

Robert Lord Jack L. Warner |

| Written by |

Play: Avery Hopwood Screenplay: Erwin S. Gelsey James Seymour Dialogue: Ben Markson David Boehm |

| Starring |

Warren William Joan Blondell Aline MacMahon Ruby Keeler Dick Powell |

| Music by |

Harry Warren (music) Al Dubin (lyrics) |

| Cinematography | Sol Polito |

| Edited by | George Amy |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 96 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $433,000[1] |

| Box office |

$2,202,000 (US) $1,029,000 (international)[1] |

Gold Diggers of 1933 is a Pre-Code Warner Bros. musical film directed by Mervyn LeRoy with songs by Harry Warren (music) and Al Dubin (lyrics), staged and choreographed by Busby Berkeley. It stars Warren William, Joan Blondell, Aline MacMahon, Ruby Keeler and Dick Powell, and features Guy Kibbee, Ned Sparks and Ginger Rogers.

The story is based on the play The Gold Diggers by Avery Hopwood, which ran for 282 performances on Broadway in 1919 and 1920.[2] The play was made into a silent film in 1923 by David Belasco, the producer of the Broadway play, as The Gold Diggers, starring Hope Hampton and Wyndham Standing, and again as a talkie in 1929, directed by Roy Del Ruth. That film, Gold Diggers of Broadway, which starred Nancy Welford and Conway Tearle, was the biggest box office hit of that year, and Gold Diggers of 1933 was one of the top-grossing films of 1933.[3] This version of Hopwood's play was written by James Seymour and Erwin S. Gelsey, with additional dialogue by David Boehm and Ben Markson.

In 2003 Gold Diggers of 1933 was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

Plot

The "gold diggers" are four aspiring actresses: Polly the ingenue (Ruby Keeler), Carol the torch singer (Joan Blondell), Trixie the comedian (Aline MacMahon), and Fay the glamour puss (Ginger Rogers).

The film was made in 1933 during the Great Depression and contains numerous direct references to it. It begins with a rehearsal for a stage show, which is interrupted by the producer's creditors who close down the show because of unpaid bills.

At the unglamorous apartment shared by three of the four actresses (Polly, Carol, and Trixie), the producer, Barney Hopkins (Ned Sparks), is in despair because he has everything he needs to put on a show, except money. He hears Brad Roberts (Dick Powell), the girls' neighbor and Polly's boyfriend, playing the piano. Brad is a brilliant songwriter and singer who not only has written the music for a show, but also offers Hopkins $15,000 in cash to back the production. Of course, they all think he's pulling their legs, but he insists that he's serious – he'll back the show, but he refuses to perform in it, despite his talent and voice.

Brad comes through with the money and the show goes into production, but the girls are suspicious that he must be a criminal since he is cagey about his past, and will not appear in the show, even though he is clearly more talented than the aging juvenile lead they have hired. It turns out, however, that Brad is in fact a millionaire's son whose family does not want him associating with the theatre. On opening night, in order to save the show when the juvenile (Clarence Nordstrom) can't perform (due to his lumbago acting up), Brad is forced to play the lead role.

With the resulting publicity, Brad's brother J. Lawrence Bradford (Warren William) and family lawyer Fanuel H. Peabody (Guy Kibbee) discover what he is doing, and go to New York to save him from being seduced by a "gold digger".

Lawrence mistakes Carol for Polly, and his heavy-handed effort to dissuade the "cheap and vulgar" showgirl from marrying Brad by buying her off annoys her so much that she goes along with the gag. Meanwhile, Trixie targets "Fanny" the lawyer as the perfect rich sap ripe for exploitation. But when the dust settles, Carol and Lawrence are in love and Trixie marries Fanuel, while Brad is free to marry Polly after all. All the "gold diggers" (except Fay) end up married to wealthy men.

Cast

- Warren William as Lawrence Bradford, Brad's brother

- Joan Blondell as Carol King, the torch singer

- Aline MacMahon as Trixie Lorraine, the comedian

- Ruby Keeler as Polly Parker, the ingenue

- Dick Powell as Brad Roberts, the songwriter and singer (aka Robert Treat Bradford)

- Guy Kibbee as Fanuel H. Peabody, the Bradford family lawyer

- Ned Sparks as Barney Hopkins, the producer

- Ginger Rogers as Fay Fortune, the glamourpuss

- Etta Moten as soloist in "Remember My Forgotten Man" (uncredited)

- Billy Barty as The Baby in "Pettin' in the Park" (uncredited)

- Cast notes

- Character actors Sterling Holloway and Hobart Cavanaugh appear in small roles, as does choreographer Busby Berkeley (as a backstage call boy who yells "Everybody on stage for the 'Forgotten Man' number").[4]

- Other uncredited cast members include Robert Agnew, Joan Barclay, Ferdinand Gottschalk, Ann Hovey, Fred Kelsey, Charles Lane, Wallace MacDonald, Wilbur Mack, Dennis O'Keefe, Fred Toones, Dorothy Wellman, Renee Whitney, Jane Wyman, and Tammany Young.[5]

Production

Gold Diggers of 1933 was originally to be called High Life, and George Brent was an early casting idea for the role played by Warren William. The film was made for an estimated $433,000,[6] at Warner Bros. studios in Burbank, and went into general release on May 27, 1933.

It was the third most popular movie at the US box office in 1933.[7]

The film made a profit of $1,602,530.[1]

Accolades

In 1934, the film was nominated for an Oscar for Best Sound Recording for Nathan Levinson, the film's sound director.[8]

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2004: AFI's 100 Years...100 Songs:

- "We're in the Money" – Nominated[9]

- 2006: AFI's Greatest Movie Musicals – Nominated[10]

Musical numbers

The film contains four song and dance sequences designed, staged and choreographed by Busby Berkeley. All the songs were written by Harry Warren and Al Dubin.[11] (In the film, when producer Barney Hopkins hears Brad's music he picks up the phone and says: "Cancel my contract with Warren and Dubin!")

"We're in the Money" is sung by Ginger Rogers accompanied by scantily-clad showgirls dancing with giant coins. Rogers sings one verse in Pig Latin.

"Pettin' in the Park" is sung by Ruby Keeler and Dick Powell. It includes a tap dance from Keeler and a surreal sequence featuring dwarf actor Billy Barty as a baby who escapes from his stroller. During the number, the women get caught in a rainstorm and go behind a backlit screen to remove their wet clothes in silhouette. They emerge in metal garments, which thwart the men's attempts to remove them, until Billy Barty gives Dick Powell a can opener. This number was originally planned to end the film.[4]

"The Shadow Waltz" is sung by Powell and Keeler. It features a dance by Keeler, Rogers, and many female violinists with neon-tubed violins that glow in the dark. Berkeley got the idea for this number from a vaudeville act he once saw - the neon on the violins was an afterthought. On March 10, the Long Beach earthquake hit while this number was being filmed:

[it] caused a blackout and short-circuited some of the dancing violins. Berkeley was almost thrown from the camera boom, dangling by one hand until he could pull himself back up. He yelled for the girls, many of whom were on a 30-foot (9.1 m)-high platform, to sit down until technicians could get the soundstage doors open and let in some light.[4]

"Remember My Forgotten Man" is sung by Joan Blondell and Etta Moten and features sets influenced by German Expressionism and a gritty evocation of Depression-era poverty. Berkeley was inspired by the May 1932 war veterans' march on Washington, D.C. When the number was finished, Jack L. Warner and Darryl F. Zanuck (the studio production head) were so impressed that they ordered it moved to the end of the film, displacing "Pettin' in the Park".[4]

An additional production number was filmed, but cut before release: "I've Got to Sing a Torch Song" was to have been sung by Ginger Rogers, but instead appears in the film sung by Dick Powell near the beginning.[4][12]

Circumventing censorship with alternate footage

According to Sin in Soft Focus: Pre-Code Hollywood by Mark A. Vieira, Gold Diggers of 1933 was one of the first American films made and distributed with alternate footage in order to circumvent state censorship problems. Busby Berkeley used lavish production numbers as a showcase of the female anatomy that were both "lyrical and lewd".[13] "Pettin' in the Park" and "We're in the Money" are prime examples of this. The state censorship boards had become so troublesome that a number of studios began filming slightly different versions of censorable scenes. In this way, when a film was edited, the "toned down" reels were labeled according to district. One version could be sent to New York City, another to the South, and another to the United Kingdom.[13]

Vieira reports that the film had two different endings: in one, the rocky romance between Warren William and Joan Blondell – whom he calls "cheap and vulgar" – is resolved backstage after the "Forgotten Man" number. In an alternate ending, this scene never takes place and the film ends with the number.[13]

See also

- The Gold Diggers (1923)

- Gold Diggers of Broadway (1929)

- Gold Diggers of 1935

- Gold Diggers of 1937

- Gold Diggers in Paris (1938)

References

- 1 2 3 Sedgwick, Jon (2000) Popular Filmgoing in 1930s Britain: A Choice of Pleasures University of Exeter Press. p.168 ISBN 9780859896603

- ↑ IBDB "The Gold Diggers"

- ↑ TCM Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 Frank Miller "Gold Diggers of 1933" TCM article

- ↑ Full cast and credits at Internet Movie Database

- ↑ IMDB Business Data

- ↑ 'Actual Receipts at the Wickets Now Decide "Box-Office Champions of 1933": Seven Ratings Entail Listing Thirteen Films Vary From Ten Voted Best; Robson Vice Barrymore; About Showshops.' The Washington Post (1923-1954) [Washington, D.C] 06 Feb 1934: 14.

- ↑ "The 6th Academy Awards (1934) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved 2011-08-07.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Songs Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-08-13.

- ↑ "AFI's Greatest Movie Musicals Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-08-13.

- ↑ TCM Music

- ↑ According to the book Sin in Soft Focus: Pre-Code Hollywood by Mark Vieira, Ginger Rogers' rendition of "I've Got to Sing a Torch Song" was cut before release simply because it slowed down the film. A still of Rogers, sitting atop a piano performing it, survives today and is shown in the book.

- 1 2 3 Vieira, Mark A. (1999). Sin in Soft Focus: Pre-Code Hollywood. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. p. 117. ISBN 0-8109-4475-8.

External links

Media related to Gold Diggers of 1933 at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Gold Diggers of 1933 at Wikimedia Commons- Gold Diggers of 1933 at the Internet Movie Database

- Gold Diggers of 1933 at the TCM Movie Database

- Gold Diggers of 1933 at AllMovie

- Gold Diggers of 1933 at Rotten Tomatoes