Great Depression of British Agriculture

The Great Depression of British Agriculture occurred during the late nineteenth century and is usually dated from 1873 to 1896.[1] The depression was caused by the dramatic fall in grain prices following the opening up of the American prairies to cultivation in the 1870s and the advent of cheap transportation with the rise of steamships. British agriculture did not recover from this depression until after the Second World War.[2][3]

Background

In 1846 Parliament repealed the Corn Laws—which had imposed a tariff on imported grain—and thereby instituted free trade. There was a widespread belief that free trade would lower prices immediately.[4][5] However this did not occur for about 25 years after repeal and the years 1853 to 1862 were famously described by Lord Ernle as the "golden age of English agriculture".[6] This period of prosperity was caused by rising prices due to the discovery of gold in Australia and California which encouraged industrial demand.[7] Grain prices dropped from 1848 to 1850 but went up again from 1853, with the Crimean War (1853-1856) and the American Civil War (1861-1865) preventing the export of cereals from Russia and America, thereby shielding Britain from the effects of free trade.[8][9] Britain enjoyed a series of good harvests (apart from in 1860) and the area of land under cultivation expanded, with increasing land values and increasing investments in drainage and buildings.[10][11] In the opinion of historian Robert Ensor, the technology employed in British agriculture was superior to most farming on the Continent due to more than a century of practical research and experimentation: "Its breeds were the best, its cropping the most scientific, its yields the highest".[12] Ernle stated that "crops reached limits which production has never since exceeded, and probably, so far as anything certain can be predicted of the unknown, never will exceed".[13]

Causes of the Depression

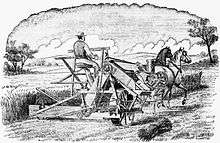

In 1862 the United States Congress passed the Homestead Act which led to the settlement of a large part of the Mid-West.[14] America also witnessed a great increase in railways, mainly across the prairies. In 1860 America possessed about 30,800 miles of railways; by 1880 this had increased to about 94,200 miles. The railway companies encouraged farmer-settlers by promising to transport their crops for less than cost for a number of years.[15] Due to the technological progress of shipping, there was for the first time plenty of cheap steam ships to transport their crops across the seas. This drove down transport costs: in 1873 the cost of transporting a ton of grain from Chicago to Liverpool was £3 7s., in 1880 it was £2 1s. and in 1884 £1 4s.[16] New inventions in agricultural machinery also aided the American prairie farmer. Due to the scarcity of hired farm labourers, prairie farmers had to collect their own harvest and the limit of their expansion was set by what one pair of hands could do. The advent of the reaper-binder in 1873 revolutionised harvesting because it meant the doubling of every farmer's crop as it enabled the reaping to be worked by one man instead of two.[17] For these reasons, cheap imports of vast amounts of American prairie wheat were able to flood the market and undercut and overwhelm British wheat farmers.[18]

The bad harvests of 1875, 1877, 1878 and particularly the wet summer of 1879 disguised the cause of the depression.[19][20][21] The Duke of Bedford wrote in 1897 that "Agriculturalists and the nation at large were alike insensible to the real character of the depression...Cheap marine transport had already thrown open the English market to the cereals of four continents...It is easy to be wise after the event, but it is strange that a catastrophe which was no longer merely impending but had actually taken place should have been regarded by those best able to judge as a passing cloud".[22] In previous seasons of bad harvests, farmers were compensated by high prices caused by the scarcity.[23][24] However British farmers could no longer rely on high prices due to the cheap American imports.[25]

Effects

Between 1871-1875 and 1896-1900, the importation of wheat and flour increased by 90%, for meat it was 300% and for butter and cheese it was 110%.[26] The price of wheat in Britain declined from 56s. od. a quarter in 1867-1871 to 27s. 3d. in 1894-1898.[27] The nadir came in 1894-1895, when prices reached their lowest level for 150 years, 22s. 10d.[28] On the eve of the depression, the total amount of land growing cereals was 9,431,000 acres; by 1898 this had declined to 7,401,000 acres, a decline of about 22%. During the same period, the amount of land under permanent pasture rather than under cultivation increased by 19%.[29] By 1900 wheat-growing land was only a little over 50% of the total of 1872 and shrank further until 1914.[30]

The depression also caused rural depopulation. The 1881 census showed a decline of 92,250 in agricultural labourers since 1871, with an increase of 53,496 urban labourers. Many of these had previously been farm workers who migrated to the cities to find employment.[31] Between 1871 and 1901 the population of England and Wales increased by 43% but the proportion of male agricultural labourers decreased by over one-third.[32] According to Sir James Caird in his evidence to the Royal Commission on the Depression in Trade and Industry in 1886, the annual income of landlords, tenants and labourers had fallen by £42,800,000 since 1876.[33] No other country witnessed such a social transformation and British policy contrasted with those adopted on the Continent.[34] Every wheat-growing country imposed tariffs in the wake of the explosion of American prairie wheat except Britain and Belgium.[35] Subsequently, Britain became the most industrialised major country with the smallest proportion of its resources devoted to agriculture.[36]

Britain's dependence on imported grain during the 1830s was 2%; during the 1860s it was 24%; during the 1880s it was 45%, for corn it was 65%.[37] By 1914 Britain was dependent on imports for four-fifths of her wheat and 40% of her meat.[38]

Social effects

Lady Bracknell:...what is your income?

Jack: Between seven and eight thousand a year.

Lady Bracknell [makes a note in her book]: In land, or in investments?

Jack: In investments chiefly.

Lady Bracknell: That is satisfactory. What between the duties expected during one's lifetime, and the duties exacted from one after one's death, land has ceased to be either a profit or a pleasure. It gives one position and prevents one from keeping it up. That's all that can be said about land.[39]

—Oscar Wilde, The Importance of Being Earnest (1895).

Between 1809 and 1879, 88% of British millionaires had been landowners; between 1880 and 1914 this figure dropped to 33% and fell further after the First World War.[40] During the first three-quarters of the nineteenth century, the British landed aristocracy were the wealthiest class in the world's richest country.[41] In 1882 Charles George Milnes Gaskell wrote that "the vast increase in the carrying power of ships, the facilities of intercourse with foreign countries, [and] the further cheapening of cereals and meat" meant that economically and politically the old landed class were no longer lords of the earth.[42] The new wealthy élite were no longer British aristocrats but American businessmen, such as Henry Ford, John D. Rockefeller and Andrew W. Mellon, who made their wealth from industry rather than land.[43] By the late nineteenth century, British manufacturers eclipsed the aristocracy as the richest class in the nation. As Arthur Balfour stated in 1909: "The bulk of the great fortunes are now in a highly liquid state...They do not consist of huge landed estates, vast parks and castles, and all the rest of it".[44]

Responses

The Prime Minister at the outset of the depression, Benjamin Disraeli, had once been a staunch upholder of the Corn Laws and had predicted ruin for agriculture if they were repealed.[45][46] However, unlike most other European governments, his government did not revive tariffs on imported cereals to save their farms and farmers.[47] Despite calls from landowners to reintroduce the Corn Laws, Disraeli responded by saying that the issue was settled and that protection was impracticable.[48] Ensor claimed that the difference between Britain and the Continent was due to the latter having conscription; rural men were thought to be the best suited as soldiers. But for Britain, with no conscript army, this did not apply.[49] He also claimed that Britain staked its future on continuing to be "the workshop of the world", as the leading manufacturing nation.[50] Robert Blake claimed that Disraeli was dissuaded from reviving protection due to the urban working class enjoying cheap imported food at a time of industrial depression and rising unemployment. Enfranchised by Disraeli in 1867, working men's votes were crucial in a general election and he did not want to antagonise them.[51]

However Disraeli's government did appoint a Royal Commission on agricultural depression. This attributed the depression to bad harvests and foreign competition.[52][53] Its final report of 1882 recommended changing the burden of local taxation from real property to the Consolidated Fund and the setting up of a government department for agriculture.[54] The government at the time, a Liberal administration under William Ewart Gladstone, did little.[55] Lord Salisbury's government founded the Board of Agriculture in 1889.[56]

After a series of droughts in the early 1890s, Gladstone's government appointed another Royal Commission into the depression in 1894. Its final report found foreign competition as the main cause in the fall in prices. It recommended changes in land tenure, tithes, education, and other minor items.[57]

Notes

- ↑ T. W. Fletcher, ‘The Great Depression of English Agriculture 1873-1896’, in P. J. Perry (ed.), British Agriculture 1875-1914 (London: Methuen, 1973), p. 31.

- ↑ Alun Howkins, Reshaping Rural England. A Social History 1850-1925 (London: HarperCollins Academic, 1991), p. 138.

- ↑ David Cannadine, The Decline and Fall of the British Aristocracy (London: Pan, 1992), p. 92.

- ↑ Mancur Olson and Curtis C. Harris, ‘Free Trade in 'Corn': A Statistical Study of the Prices and Production of Wheat in Great Britain from 1873 to 1914’, in P. J. Perry (ed.), British Agriculture 1875-1914 (London: Methuen, 1973), p. 150.

- ↑ Richard Perren, Agriculture in Depression, 1870-1940 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), p. 2.

- ↑ Lord Ernle, English Farming Past and Present. Sixth Edition (Chicago: Quadrangle Books, 1961), p. 373.

- ↑ Perren, p. 2.

- ↑ Perren, p. 3.

- ↑ P. J. Perry, ‘Editor's Introduction’, British Agriculture 1875-1914 (London: Methuen, 1973), p. xix.

- ↑ Perren, p. 3.

- ↑ Ernle, pp. 374-375.

- ↑ R. C. K. Ensor, England 1870-1914 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1936), p. 117.

- ↑ Ernle, p. 375.

- ↑ H. M. Conacher, ‘Causes of the Fall of Agricultural Prices between 1875 and 1895’, in P. J. Perry (ed.), British Agriculture 1875-1914 (London: Methuen, 1973), p. 22.

- ↑ Ensor, p. 115.

- ↑ Ensor, p. 115.

- ↑ Ensor, pp. 115-116.

- ↑ Ensor, p. 115.

- ↑ Perry, p. xix, p. xxiii.

- ↑ Perren, p. 7.

- ↑ Howkins, p. 138, p. 140.

- ↑ The Duke of Bedford, The Story of a Great Agricultural Estate (London: John Murray, 1897), p. 181.

- ↑ Perren, p. 7.

- ↑ Perry, p. xviii.

- ↑ Ensor, p. 116.

- ↑ Fletcher, p. 33.

- ↑ Fletcher, p. 34.

- ↑ Ernle, p. 385.

- ↑ Howkins, p. 146.

- ↑ Ensor, p. 285.

- ↑ Ensor, p. 117.

- ↑ Ensor, pp. 285-286.

- ↑ Ernle, p. 381.

- ↑ Perren, p. 24.

- ↑ Ensor, p. 116.

- ↑ Olson and Harris, p. 149.

- ↑ Ensor, p. 116.

- ↑ Arthur Marwick, The Deluge: British Society and the First World War. Second Edition (London: Macmillan, 1991), p. 58.

- ↑ Howkins, p. 152.

- ↑ Cannadine, p. 91.

- ↑ Cannadine, p. 90.

- ↑ Cannadine, p. 90.

- ↑ Cannadine, p. 90.

- ↑ Cannadine, p. 91.

- ↑ William Flavelle Monypenny and George Earle Buckle, The Life of Benjamin Disraeli, Earl of Beaconsfield. Volume II. 1860–1881 (London: John Murray, 1929), p. 1242.

- ↑ Robert Blake, Disraeli (London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1966), p. 698.

- ↑ Ensor, p. 54.

- ↑ Blake, p. 698.

- ↑ Ensor, p. 54.

- ↑ Ensor, p. 118.

- ↑ Blake, pp. 698-699.

- ↑ Ernle, p. 380.

- ↑ Fletcher, p. 45.

- ↑ Fletcher, p. 46.

- ↑ Fletcher, p. 46.

- ↑ Fletcher, p. 46.

- ↑ Ensor, p. 286.

References

- The Duke of Bedford, The Story of a Great Agricultural Estate (London: John Murray, 1897).

- David Cannadine, The Decline and Fall of the British Aristocracy (London: Pan, 1992).

- H. M. Conacher, ‘Causes of the Fall of Agricultural Prices between 1875 and 1895’, in P. J. Perry (ed.), British Agriculture 1875-1914 (London: Methuen, 1973), pp. 8-29.

- R. C. K. Ensor, England 1870-1914 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1936).

- Lord Ernle, English Farming Past and Present. Sixth Edition (Chicago: Quadrangle Books, 1961).

- T. W. Fletcher, ‘The Great Depression of English Agriculture 1873-1896’, in P. J. Perry (ed.), British Agriculture 1875-1914 (London: Methuen, 1973), pp. 30-55.

- Alun Howkins, Reshaping Rural England. A Social History 1850-1925 (London: HarperCollins Academic, 1991).

- Mancur Olson and Curtis C. Harris, ‘Free Trade in 'Corn': A Statistical Study of the Prices and Production of Wheat in Great Britain from 1873 to 1914’, in P. J. Perry (ed.), British Agriculture 1875-1914 (London: Methuen, 1973), pp. 149-176.

- Christable S. Orwin and Edith H. Whetham, History of British Agriculture 1846-1914 (Newton Abbot: David & Charles, 1971).

- Richard Perren, Agriculture in Depression, 1870-1940 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995).

- P. J. Perry, ‘Editor's Introduction’, British Agriculture 1875-1914 (London: Methuen, 1973), pp. xi-xliv.

- F. M. L. Thompson, English Landed Society in the Nineteenth Century (London: Routledge, 1971).

Further reading

- E. J. T. Collins (ed.), The Agrarian History of England and Wales. Volume VII: 1850-1914 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011).