Gun violence

Gun related violence is violence committed with the use of a gun (firearm or small arm). Gun related violence may or may not be considered criminal. Criminal, includes homicide (except when and where ruled justifiable), assault with a deadly weapon, and suicide, or attempted suicide, depending on jurisdiction. Non-criminal violence may include accidental or unintentional injury and death. Included in this subject are statistics regarding military or para-military activities, as well as the actions of civilians.

According to GunPolicy.org, 75 percent of the world's 875 million guns are civilian controlled.[1] Globally, millions are wounded through the use of guns.[1] Assault by firearm resulted in 180,000 deaths in 2013 up from 128,000 deaths in 1990.[2] There were additionally 47,000 unintentional firearm related deaths in 2013.[2]

Levels of gun related violence vary greatly among geographical regions, countries, and even subnationally.[3] The United States has the highest rate of gun related deaths per capita among developed countries,[4]:29 though it also has the highest rate of gun ownership and the highest rate of officers. Mother Jones has found that, in the United States, "gun death rates tend to be higher in states with higher rates of gun ownership." It has also found that "[g]un death rates are generally lower in states with restrictions such as assault-weapons bans or safe-storage requirements."[5]

Gun control is a very controversial topic in the United States of America today. Gun control is defined as “Laws or policies that regulate within a jurisdiction the manufacture, sale, transfer, possession, modification, or use of firearms by civilians”. (The Simple Truth About Gun Control). Often, the Second Amendment is referenced by those both in favor and against gun control because while guns have played an integral role in America's history, they have also caused much destruction. Due to recent mass shootings in the United States in schools, movie theaters, night clubs, etc. this issue has come to the forefront of many political and everyday debates.

According to the United Nations, Deaths from small firearms exceed that of all other weapons combined, and more die each year from gun related violence than did in the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki combined.[6] The global death toll from use of guns may number as high as 1,000 dead each day.[6]

Prevention

A number of ideas have been proposed on how to lessen the incidence of gun related violence.

Some propose keeping a gun at home to keep one safer. Mother Jones has reported that "[o]wning a gun has been linked to higher risks of homicide, suicide, and accidental death by gun."[5] According to the FBI, gun related violence is linked to gun ownership and is not a function or byproduct of crime. Their study indicates that more than 90% of gun related deaths were not part of a commission of a crime, rather they were directly related to gun ownership.[7][8] Some propose keeping a gun for self-defense, however Mother Jones reports that [a] Philadelphia study found that the odds of an assault victim being shot were 4.5 times greater if he carried a gun" and that "[h]is odds of being killed were 4.2 times greater" when armed.[5] Other studies have concluded that firearm possession provides a deterrent benefit. "Research conducted by Professors James Wright and Peter Rossi, for a landmark study funded by the U.S. Department of Justice, points to the armed citizen as possibly the most effective deterrent to crime in the nation. Wright and Rossi questioned over 1,800 felons serving time in prisons across the nation" [9] Others propose arming civilians to counter mass shootings. FBI research shows that between 2000 and 2013 "In 5 incidents (3.1%), the shooting ended after armed individuals who were not law enforcement personnel exchanged gunfire with the shooters." [10] Another proposal is to expand self defense laws for cases where a person is being aggressed upon, although "those policies have been linked to a 7 to 10% increase in homicides" (that is, shootings where self-defense cannot be claimed).[5]

Types

Suicide

There is a strong relationship between guns in the home, as well as access to guns more generally, and suicide risk, the evidence for which is strongest in the United States.[11][12] A 1992 U.S. medical journal report shows an association between household firearm ownership and gun suicide rates, finding that individuals in a firearm owning home are close to five times more likely to commit suicide than those individuals who do not own firearms.[13] A 2002 study found that access to guns in the home was associated with an increased risk of suicide among middle-aged and older adults, even after controlling for psychiatric illness.[14] As of 2008, there were 12 case-control studies that had been conducted in the U.S., all of which had found that guns in the home were associated with an increased risk of suicide.[15] However, a 1996 New Zealand study found no significant relationship between household guns and suicide.[16] Assessing data from 14 developed countries where gun ownership levels were known, the Harvard Injury Control Research Center found statistically significant correlations between those levels and suicide rates. However, the parallels were lost when data from additional nations was included.[17]:30 A 2006 study found a significant effect of changes in gun ownership rates on gun suicide rates in multiple Western countries.[18] During the 1980s and 1990s, the rate of adolescent suicides with guns caught up with adult rates, and the 75-and-older rate rose above all others.[4]:20–21[19] The use of firearms in suicides ranges from less than 10 percent in Australia[20] to 50 percent in the United States, where it is the most common method[21] and where suicides outnumber homicides 2-to-1.[22]

According to U.S. criminologist Gary Kleck, studies that try to link gun ownership to victimology often fail to account for the presence of guns owned by other people.[23] Research by economists John Lott of the U.S. and John Whitley of Australia indicates that safe-storage laws do not appear to affect juvenile accidental gun-related deaths or suicides.[24] In contrast, a 2004 study led by Daniel Webster found that such laws were associated with slight reductions in suicide rates among children. The same study criticized Lott and Whitley's study on the subject for inappropriately using a Tobit model.[25] A committee of the U.S. National Research Council said ecological studies on violence and firearms ownership provide contradictory evidence. The committee wrote: "[Existing] research studies and data include a wealth of descriptive information on homicide, suicide, and firearms, but, because of the limitations of existing data and methods, do not credibly demonstrate a causal relationship between the ownership of firearms and the causes or prevention of criminal violence or suicide."[26]

Intentional homicide

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) defines intentional homicide as "acts in which the perpetrator intended to cause death or serious injury by his or her actions." This excludes deaths: related to conflicts (war); caused by recklessness or negligence; or justifiable, such as in self-defense or by law enforcement in the line of duty.[3] A 2009 report by the Geneva Declaration using UNODC data showed that worldwide firearms were used in an average of 60 percent of all homicides.[27]:67 In the U.S. in 2011, 67 percent of homicide victims were killed by a firearm: 66 percent of single-victim homicides and 79 percent of multiple-victim homicides.[28] In 2009, the United States' homicide rate was reported to be 5.0 per 100,000.[29] A 2016 Harvard study claims that in 2010 the homicide rate was about 7 times higher than that of other high-income countries, and that the US gun homicide rate was 25.2 times higher.[30] Another Harvard study found that higher gun availability was strongly correlated with higher homicide rates across 26 high-income countries.[31] Access to guns is associated with an increased risk of being the victim of homicide.[12]

Domestic violence

Some gun control advocates say that the strongest evidence linking availability of guns to death and injury is found in domestic violence studies, often referring to those by public health policy analyst Arthur Kellermann. In response to suggestions by some that homeowners would be wise to acquire firearms for protection from home invasions, Kellermann investigated in-home homicides in three cities over five years. He found that the risk of a homicide was in fact slightly higher in homes where a handgun was present. The data showed that the risk of a crime of passion or other domestic dispute ending in a fatal injury was higher when a gun was readily available (essentially loaded and unlocked) compared to when no gun was readily available. Kellerman said this increase in mortality overshadowed any protection a gun might have deterring or defending against burglaries or invasions. He also concluded that further research of domestic violence causes and prevention are needed.[32]

Critics of Kellermann's study say that it is more directly a study of domestic violence than of gun ownership. Gary Kleck and others dispute the work.[33][34] Kleck says that few of the homicides that Kellermann studied were committed with guns belonging to the victim or members of his or her household, and that it was implausible that victim household gun ownership contributed to their homicide. Instead, according to Kleck, the association that Kellermann found between gun ownership and victimization reflected that people who live in more dangerous circumstances are more likely to be murdered, but also were more likely to have acquired guns for self-protection.[35]

Robbery and assault

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime defines robbery as the theft of property by force or threat of force. Assault is defined as a physical attack against the body of another person resulting in serious bodily injury. In the case of gun related violence, the definitions become more specific and include only robbery and assault committed with the use of a firearm.[36] Firearms are used in this threatening capacity four to six times more than firearms used as a means of protection in fighting crime.[37][38] Hemenway's figures are disputed by other academics, who assert there are many more defensive uses of firearms than criminal uses. See John Lott's "More Guns, Less Crime".

In terms of occurrence, developed countries have similar rates of assaults and robberies with firearms, whereas the rates of homicides by firearms vary greatly by country.[4][39]

Costs of gun related violence

Violence committed with guns leads to significant public health, psychological, and economic costs.

Economic costs

Aside from the human costs like the emotional toll of losing a loved one, the purely economic cost of gun related violence in the United States is $229 billion a year,[40] meaning a single murder has average direct costs of almost $450,000, from the police and ambulance at the scene, to the hospital, courts, and prison for the murderer.[40] A 2014 study found that from 2006 to 2010, gun-related injuries in the United States cost $88 billion.[41]

Public health

Assault by firearm resulted in 180,000 deaths worldwide in 2013, up from 128,000 deaths worldwide in 1990.[2] There were 47,000 unintentional firearm deaths worldwide in 2013.[2]

Emergency medical care is a major contributor to the monetary costs of such violence. It was determined in a study that for every firearm death in the United States for the year beginning 1 June 1992, an average of three firearm-related injuries were treated in hospital emergency departments.[42]

Psychological

Children exposed to gun related violence, whether they are victims, perpetrators, or witnesses, can experience negative psychological effects over the short and long terms. Psychological trauma also is common among children who are exposed to high levels of violence in their communities or through the media.[43] Psychologist James Garbarino, who studies children in the U.S. and internationally, found that individuals who experience violence are prone to mental and other health problems, such as post-traumatic stress disorder and sleep deprivation. These problems increase for those who experience violence as children.[44]

Gun Related Violence in Australia

Port Arthur

.jpg)

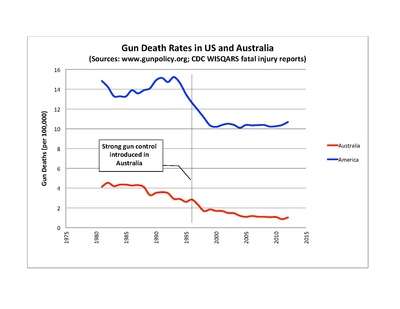

The Port Arthur massacre in 1996 Australia, horrified the Australian public. The gunman opened fire on shop owners and tourists killing 35 people, and wounding 23. This massacre, although horrible and disgusting, kick started Australia’s laws against guns. The Prime Minister at that time, John Howard, proposed a gun law that prevented the public from having all semi-automatic rifles, all semi-automatic and pump-action shotguns, in addition to a tightly restrictive system of licensing and ownership controls. Of course it was no surprise that gun enthusiasts were outraged, which worried John Howard. So during the time he held public meetings, he had a bullet proof vest on the whole time, which was indeed visible.

The government also bought back guns from people. In 1996-2003 it was estimated they bought back and destroyed nearly 1 million firearms. By the end of 1996, whilst Australia was still reeling from the Port Arthur massacre, the gun law was fully in place. Since then, the number of deaths related to gun related violence dwindled almost every year. In 1979 six hundred and eighty-five people[45] died due to gun violence, and in 1996 it was five hundred and sixteen. Since then, the numbers just continue to drop. In 2011 just one hundred and eighty-eight deaths, and more recently in 2014, two hundred and thirty deaths.[46]

Sydney Siege

On the Australia's most mediated gun violence related incident since Port Arthur, was the 2014 Sydney Hostage Crisis. On 15–16 December 2014, a lone gunman, Man Haron Monis, held hostage 17 customers and employees of a Lindt chocolate café. The perpetrator was on bail at the time, and had previously been convicted of a range of offences.[47][48]

The following year in August, the New South Wales Government tightened the laws of bail and illegal firearms, creating a new offence for the possession of a stolen firearm, with a maximum of 14 years imprisonment.[49]

See also

- Armed violence reduction

- List of countries by firearm-related death rate

- Global gun cultures

- Gunfire locator

- Gun violence in the United States

References

- 1 2 Alpers, Philip; Wilson, Marcus (2013). "Global Impact of Gun Violence". gunpolicy.org. Sydney School of Public Health, The University of Sydney. Retrieved February 25, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators (17 December 2014). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013.". Lancet. 385: 117–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604

. PMID 25530442.

. PMID 25530442. - 1 2 "Global Study on Homicide 2011". United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). Retrieved December 18, 2012.

- 1 2 3 Cook, Philip J.; Ludwig, Jens (2000). Gun Violence: The Real Costs. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195137934. OCLC 45580985.

- 1 2 3 4 "10 Pro-Gun Myths, Shot Down". Mother Jones.

- 1 2 http://www.gunpolicy.org/firearms/region/

- ↑ Justice, National Center for Juvenile. "Easy Access to the FBI's Supplementary Homicide Reports". www.ojjdp.gov. Retrieved 2016-04-05.

- ↑ "The Gun Violence Stats the NRA Doesn't Want You to Consider". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 2016-04-05.

- ↑ "Gun Control Research - Wright and Rossi Department of Justice Study (deterrent effect of armed citizens upon criminal behavior)" (PDF). Leg.state.co.us. Retrieved 2016-04-01.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on December 10, 2015. Retrieved December 3, 2015.

- ↑ Brent, David A. (25 January 2006). "Firearms and Suicide". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 932 (1): 225–240. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb05808.x.

- 1 2 Anglemyer, Andrew; Horvath, Tara; Rutherford, George (21 January 2014). "The Accessibility of Firearms and Risk for Suicide and Homicide Victimization Among Household Members". Annals of Internal Medicine. 160 (2): 101–110. doi:10.7326/M13-1301.

- ↑ Kellerman, Arthur L.; Rivara, Frederick P. (August 13, 1992). "Suicide in the Home in Relation to Gun Ownership". The New England Journal of Medicine. Massachusetts Medical Society. 327 (7): 467–472. doi:10.1056/NEJM199208133270705. PMID 1308093.

- ↑ Conwell, Yeates; Duberstein, Paul R.; Connor, Kenneth; Eberly, Shirley; Cox, Christopher; Caine, Eric D. (July 2002). "Access to Firearms and Risk for Suicide in Middle-Aged and Older Adults". The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 10 (4): 407–416. doi:10.1097/00019442-200207000-00007.

- ↑ Miller, Matthew; Hemenway, David (4 September 2008). "Guns and Suicide in the United States". New England Journal of Medicine. 359 (10): 989–991. doi:10.1056/NEJMP0805923.

- ↑ Beautrais, Annette L.; Joyce, Peter R.; Mulder, Roger T. (December 1996). "Access to firearms and the risk of suicide: a case control study". Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 30 (6): 741–748. doi:10.3109/00048679609065040. PMID 9034462.

- ↑ Miller, Matthew; Hemenway, David (2001). "Firearm Prevalence and the Risk of Suicide: A Review" (PDF). Harvard Health Policy Review. Exploring Policy in Health Care (EPIHC). 2 (2): 29–37.

One study found a statistically significant relationship between gun ownership levels and suicide rate across 14 developed nations (e.g. where survey data on gun ownership levels were available), but the association lost its statistical significance when additional countries were included.

- ↑ Ajdacic-Gross, Vladeta; Killias, Martin; Hepp, Urs; Gadola, Erika; Bopp, Matthias; Lauber, Christoph; Schnyder, Ulrich; Gutzwiller, Felix; Rössler, Wulf (October 2006). "Changing Times: A Longitudinal Analysis of International Firearm Suicide Data". American Journal of Public Health. 96 (10): 1752–1755. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2005.075812.

- ↑ Ikeda, Robin M.; Gorwitz, Rachel; James, Stephen P.; Powell, Kenneth E.; Mercy, James A. (1997). "Fatal Firearm Injuries in the United States 1962-1994". Violence Surveillance Summary. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. 3.

- ↑ Harrison, James E.; Pointer, Sophie; Elnour, Amr Abou (July 2009). "A review of suicide statistics in Australia" (PDF). aihw.gov.au. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

- ↑ McIntosh, JL; Drapeau, CW (November 28, 2012). "U.S.A. Suicide: 2010 Official Final Data" (PDF). suicidology.org. American Association of Suicidology. Retrieved February 25, 2014.

- ↑ "Twenty Leading Causes of Death Among Persons Ages 10 Years and Older, United States". National Suicide Statistics at a Glance. Centers for Disease Control. 2009. Retrieved February 17, 2013.

- ↑ Kleck, Gary (2004). "Measures of Gun Ownership Levels of Macro-Level Crime and Violence Research" (PDF). Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. Sage Publications. 41 (1): 3–36. doi:10.1177/0022427803256229. NCJ 203876.

Studies that attempt to link the gun ownership of individuals to their experiences as victims (e.g., Kellermann, et al. 1993) do not effectively determine how an individual's risk of victimization is affected by gun ownership by other people, especially those not living in the gun owner's own household.

- ↑ Lott, John R.; Whitley, John E. (2001). "Safe-Storage Gun Laws: Accidental Deaths, Suicides, and Crime" (PDF). Journal of Law and Economics. 44 (2): 659–689. doi:10.1086/338346.

It is frequently assumed that safe-storage laws reduce accidental gun deaths and total suicides. We find no support that safe-storage laws reduce either juvenile accidental gun deaths or suicides.

- ↑ Webster, Daniel W. (4 August 2004). "Association Between Youth-Focused Firearm Laws and Youth Suicides". JAMA. 292 (5): 594. doi:10.1001/jama.292.5.594.

- ↑ National Research Council (2004). "Executive Summary". In Wellford, Charles F.; Pepper, John V.; Petrie, Carol V. Firearms and Violence: A Critical Review. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. ISBN 978-0-309-09124-4.

- ↑ "Lethal Encounters: Non-conflict Armed Violence" (PDF). Global Burden of Armed Violence 2008. Geneva, Switzerland: Geneva Declaration Secretariat. September 2008. pp. 67–88. ISBN 978-2-8288-0101-4. by Geneva Declaration editors using UNODC data.

- ↑ Cooper, Alexia; Smith, Erica L. (December 30, 2013). "Homicide in the U.S. Known to Law Enforcement, 2011". bjs.gov. U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics. Retrieved February 28, 2014.

- ↑ "Global Study on Homicide" (PDF). Unodc.org. 2011. Retrieved 2016-04-01.

- ↑ Grinshteyn, E; Hemenway, D (March 2016). "Violent Death Rates: The US Compared with Other High-income OECD Countries, 2010.". The American journal of medicine. 129 (3): 266–73. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.10.025. PMID 26551975.

- ↑ Hemenway, D; Miller, M (December 2000). "Firearm availability and homicide rates across 26 high-income countries.". The Journal of Trauma. 49 (6): 985–8. PMID 11130511.

- ↑ Kellerman, Arthur L.; Rivara, Frederick P. (October 7, 1993). "Gun ownership as a risk factor for homicide in the home". The New England Journal of Medicine. Massachusetts Medical Society. 329 (15): 1084–1091. doi:10.1056/NEJM199310073291506. PMID 8371731.

- ↑ Suter, Edgar A. (March 1994). "Guns in the medical literature--a failure of peer review". Journal of the Medical Association of Georgia. 83 (13): 133–148. PMID 8201280.

- ↑ Kates, Don B.; Schaffer, Henry E.; Lattimer, John K.; Murray, George B.; Cassem, Edwin H. (1995). Kopel, David B., ed. Guns: Who Should Have Them?. New York: Prometheus Books. pp. 233–308. ISBN 9780879759582. in chapter "Bad Medicine: Doctors and Guns." Orig. pub. 1994 in Tennessee Law Review as "Guns and Public Health: Epidemic of Violence or Pandemic of Propaganda?"

- ↑ Kleck, Gary (February 2001). "Can Owning a Gun Really Triple the Owner's Chances of being Murdered?". Homicide Studies. SAGE. 5 (1): 64–77. doi:10.1177/1088767901005001005.

- ↑ "United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime: Data". unodc.org. UNODC. August 29, 2013. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

- ↑ David Hemenway; Deborah Azrael; D Hemenway (2000). "The Relative Frequency of Offensive and Defensive Gun Uses: Results from a National Survey". Violence and Victims. 15 (3): 257–272. PMID 11200101.

- ↑ Hemenway, David; Azrael, Deborah; Miller, Matthew (2000). "Gun use in the United States: results from two national surveys". Injury Prevention. 6 (4): 263–267. doi:10.1136/ip.6.4.263. PMC 1730664

. PMID 11144624.

. PMID 11144624. - ↑ Zimring, Franklin E.; Hawkins, Gordon (1997). Crime Is Not the Problem: Lethal Violence in America. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195131055. OCLC 860399367.

- 1 2 (A. Peters. (2015) The Staggering Costs Of Gun Violence In The U.S. Every Year retrieved from http://www.fastcoexist.com/3047682/the-staggering-costs-of-gun-violence-in-the-us-every-year)

- ↑ Lee, Jarone; Quraishi, Sadeq A.; Bhatnagar, Saurabha; Zafonte, Ross D.; Masiakos, Peter T. (May 2014). "The economic cost of firearm-related injuries in the United States from 2006 to 2010". Surgery. 155 (5): 894–898. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2014.02.011.

- ↑ Annest, Joseph L.; Mercy, James A.; Gibson, Delinda R.; Ryan, George W. (June 14, 1995). "National Estimates of Nonfatal Firearm-Related Injuries: Beyond the Tip of the Iceberg". JAMA. American Medical Association. 273 (22): 1749–54. doi:10.1001/jama.1995.03520460031030. PMID 7769767.

- ↑ (Kathleen R. Patti L. Richard E.B. (2002) children, youth and gun violence. Retrieved from http://futureofchildren.org/publications/journals/article/index.xml?journalid=42&articleid=162§ionid=1035 )

- ↑ Garbarino, James; Bradshaw, Catherine P.; Vorrasi, Joseph A. (2002). "Children, Youth, and Gun Violence" (PDF). The Future of Children. David and Lucile Packard Foundation. 12 (2). ISSN 1054-8289.

- ↑ Kreisfeld, Renate. 2006. ‘Australia Revised Firearm Deaths 1979-2003.’ National Injury Surveillance Unit / NISU. Adelaide: Research Centre for Injury Studies, Flinders University of South Australia. 1 March

- ↑ GunPolicy.org. 2016. ‘Calculated Numbers of Gun Deaths - Australia.’ Causes of Death, Australia, 2014; 3303.0, Table 1.2 (Chapter XX). Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics. 14 March.)

- ↑ "Sydney siege: What we do and don't know". 2014-12-15. Retrieved 2016-09-26.

- ↑ "Victims of Sydney siege hailed as heroes after they die protecting hostages". Retrieved 2016-09-26.

- ↑ "Firearms and prohibited weapons offences". www.judcom.nsw.gov.au. Retrieved 2016-09-26.

Further reading

Library resources in your library about gun violence

External links

- Firearm-related deaths in the United States and 35 other high- and upper-middle-income countries Krug, Powell, and Dahlberg (1998)

- Gun ownership, suicide and homicide: An international perspective Killias (1992)

- GunPolicy.org Armed violence and gun laws, country by country

- Guns and suicide: Possible effects of some specific legislation Rich, Young, Fowler et al. (1990)

- Guns, Violent Crime, and Suicide in 21 Countries Killias, van Kesteren, Rindlisbacher (2001)

- State of crime and criminal justice worldwide United Nations (2010)

- World crime trends and emerging issues and responses in the field of crime prevention and criminal justice United Nations (2013)

- Gun Violence Archive (GVA) Data on each verified gun related incident, with annual statistics

- Report US Anti-gun violence activist art project, Eileen Boxer (2016)