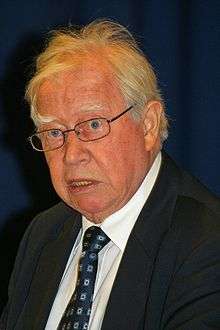

Hans Mommsen

| Hans Mommsen | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

5 November 1930 Marburg, Weimar Germany |

| Died |

5 November 2015 (aged 85) Tutzing, Germany |

| Nationality | German |

| Occupation | Historian |

| Known for | For his studies in German social history, and for his functionalist interpretation of the Third Reich, especially for arguing that Hitler was a "weak dictator" |

Hans Mommsen (5 November 1930 – 5 November 2015) was a German historian.

Life and career

Mommsen was born in Marburg, the child of the historian Wilhelm Mommsen and great-grandson of the historian of Rome Theodor Mommsen.[1] He was the twin brother of historian Wolfgang Mommsen. He studied German, history and philosophy at the University of Heidelberg, the University of Tübingen and the University of Marburg.[1] Mommsen served as professor at Tübingen (1960–1961), Heidelberg (1963–1968) and at the University of Bochum (since 1968).[1] He married Margaretha Reindel in 1966.[1] He was a member of the Social Democratic Party of Germany from 1960 until his death. He died on 5 November 2015.[2]

Early work

Much of Mommsen's early work concerned the history of the German working class, both as an object of study itself and as a factor in the larger German society.[1] Mommsen's 1979 book, Arbeiterbewegung und nationale Frage (The Labour Movement and the National Question), a collection of his essays written in the 1960s–70s was the conclusion of his studies in German working class history.[1] Mommsen much prefers writing essays to books.[1]

Functionalism and the "Weak Dictator" Thesis

Mommsen is a leading expert on Nazi Germany and the Holocaust.[1] He is a functionalist in regard to the origins of the Holocaust, seeing the Final Solution as a result of the "cumulative radicalization" of the German state as opposed to a long-term plan on the part of Adolf Hitler.[1] In Mommsen's view, Hitler was an intense anti-semite but lacked a real idea of what he wanted to do with Jews.[3] The picture Mommsen has consistently drawn of the Final Solution is of an aloof Hitler largely unwilling and incapable of active involvement in administration who presided over an incredibly disorganized regime.[3] Mommsen has forcefully contended that the Holocaust cannot be explained as a result of Hitler alone, but was instead the product of a fractured decision making process in Nazi Germany which caused the "cumulative radicalization" which led to the Holocaust.[4] Furthermore, for Mommsen, Hitler played little or no real role in the development of the Holocaust, instead preferring to let his subordinates take the initiative.[4] Instead, the "Final Solution" was caused primarily by the German bureaucracy who as the result of bureaucratic turf wars, started to compete with one another for the favor of a distant and lazy leader by engaging in ever more radical anti-semitic measures between 1933 and 1941.[4]

In Mommsen's view, Hitler's speeches encouraged his followers to carry out his "utopian" ranting about the Jews, but Hitler did not issue an order for the Holocaust and had little to do with its actual implementation.[3] In Mommsen's view, the fact that Hitler never referred explicitly to the "Final Solution" even in the privacy of his own circle was his way of avoiding personal responsibility for that which he had allowed to take place and had encouraged through his anti-semitic rhetoric.[4] As such, Mommsen has denied that Hitler ever gave any sort of order for the Holocaust, written or unwritten.[4] Mommsen has argued that Hitler did give the order for the Kommissarbefehl (Commissar Order) of 1941, that helped lead to the Holocaust, but was not part of the Holocaust proper.[4] Mommsen wrote that Hitler was the "ideological and political originator" of the Holocaust, a "utopian objective" that came to life "only in the uncertain light of the Dictator's fanatical propaganda utterances, eagerly seized upon as orders for action by men wishing to prove their diligence, the efficiency of their machinery and their political indispensability".[4] Starting with his 1966 book, Beamtentum im Dritten Reich (Civil Servants in the Third Reich), Mommsen has argued for the massive involvement of various elements in German society in the Third Reich, as against the traditional view in Germany that Nazi crimes were the work of a few criminals entirely unrepresentative of German society.[1]

Mommsen is best known for arguing that Adolf Hitler was a "weak dictator" who rather than acting decisively, reacted to various social pressures. Mommsen is opposed to the notion of Nazi Germany as a totalitarian state.[1] In Mommsen's view, Hitler was:

"unwilling to take decisions, frequently uncertain, exclusively concerned with upholding his prestige and personal authority, influenced in the strongest fashion by his current entourage, in some aspects a weak dictator".[5]

Mommsen was the first to call Hitler a "weak dictator" when he wrote in a 1966 essay that Hitler was "in all questions which needed the adoption of a fundamental and definitive position, a weak dictator".[5] In his view, the Nazis were far too disorganized ever to be a totalitarian dictatorship. In Mommsen's view, the fact that the majority of the German people supported or were indifferent to Nazism is what enabled the Nazis to stay in power.[1] Mommsen has argued that the differences between the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and the National Socialist German Workers Party are such as to render any concept of totalitarianism moot.[6] Mommsen noted that in the Soviet Union, the Soviet state was firmly subordinated to the CPSU, whereas in Nazi Germany the NSDAP functioned as a rival power structure to the German state. Writing in highly aggressive language, Mommsen has from the mid-1960s argued for the "weak dictator" thesis.[7] In a debate with Klaus Hildebrand in 1976, Mommsen argued against "personalistic" theories of the Third Reich as explaining little and providing an attempt to retroactively provide Hitler with a sense of vision that he did not possess.[7] Mommsen argued that Hitler did not have a set of rational political beliefs to operate from, and instead held a very few strongly held, but vague ideas that were not capable of providing a basis for rational thinking.[7] Mommsen argued against Hildebrand that Hitler operated largely as an opportunistic showman concerned only with the best way of promoting his image in the here and now with no regard for the future.[7] As such, Hitler's statements in his speeches were mere propaganda instead of being "firm statements of intent".[7] Mommsen has argued that both domestic and foreign policy in the Third Reich were merely a long series of incoherent drift as the Nazi regime reacted in an ad hoc fashion to crisis after crisis, leading to the "cumulative radicalization".[7]

Mommsen has argued against the "Master of the Third Reich"/intentionalist thesis by arguing that the Holocaust can not be explained as the result of Hitler's will and intentions.[7] In Mommsen's view, the evidence is simply lacking that Hitler or anyone else in the Nazi regime had any sort of masterplan, and instead Mommsen has contended that the Third Reich was simply a jumble of rival institutions feuding with one another.[7] Mommsen wrote:

"Hitler's role as a driving force, which with the same inner compulsion drove on to self-destruction, should not be underestimated. On the other hand, it must be recognized that the Dictator was only the extreme exponent of a chain of antihumanitarian impulses set free by the lapse of all institutional, legal, and moral barriers, and once set in motion, regenerating themselves in magnified form".[7]

Mommsen has pointed out that on the economic and Church questions, Hitler was not the leading radical, and that for historians it is too easy "to emphasize as the final cause of the criminal climax and terroristic hubris of National Socialist policy the determining influence of Hitler".[8] Moreover, Mommsen has maintained that because the role of Hitler has been inflated by historians, the role of traditional German elites in supporting the Nazi "restoration of social order" has been accordingly overlooked.[9] Mommsen has argued that historians should not reduce the study of the Nazi period to "the Hitler phenomenon", but must take a broader look at the factors in German society which allow the Holocaust to occur.[9]

In this respect, it may be of interest that Mommsen—at the time employed by the Munich-based Institute for Contemporary History—was the first historian in the early 1960s to accept the conclusions of the journalist Fritz Tobias who argued in a 1961 book The Reichstag Fire that the Reichstag fire of 1933 was not started by the Nazis and that Marinus van der Lubbe had acted alone.[1] Until the publication of Tobias's book, it was generally accepted both in West Germany and abroad that the fire was instigated by the Nazis as part of a plot to abolish democracy. The Nazi Machtergreifung (Seizure of Power) had been generally represented as part of a well-planned, totalitarian assault on democracy with the German people as hapless bystanders. The significance of the conclusion that the Nazis did not set the fire is that it suggests that the Machtergreifung was more of a series of ad hoc responses to events rather the result of some master plan of the part of Adolf Hitler and thus the German people were not mere bystanders.

Together with his friend Martin Broszat, Mommsen developed the structuralist interpretation of the Third Reich, that saw the Nazi state as a chaotic collection of rival bureaucracies engaged in endless power struggles.[1] In Mommsen's view, it was these power struggles that provided the dynamism that drove the German state into increasingly radical measures, leading to what Mommsen has often called the "realization of the unthinkable."

In regards to the debate about foreign policy, Mommsen has argued that German foreign policy did not follow a "programme" during the Nazi era, but was instead "expansion without object" as the foreign policy of the Reich driven by powerful internal forces sought expansion in all directions.[10] Mommsen wrote:

"...it is questionable, too, whether National Socialist foreign policy can be considered as an unchanging pursuit of established priorities. Hitler's foreign policy aims, purely dynamic in nature, knew no bounds; Joseph Schumpeters's reference to "expansion without object" is entirely justified. For this very reason, to interpret their implementation as any way consistent or logical is highly problematic...In reality, the regime's foreign policy ambitions were many and varied, without clear aims, and only linked by the ultimate goal: hindsight alone gives them some air of consistency".[10]

In Mommsen's view, the only determinate with German foreign policy was the need to maintain prestige with the German public.[11] In a Primat der Innenpolitik ("primacy of domestic politics") argument, Mommsen wrote that the foreign policy of the Third Reich "was its form domestic policy projected outwards, which was able to conceal the increasing loss of reality only by maintaining political dynamism through incessant action. As such it became ever more distant from the chance of political stabilization".[11]

Mommsen has faced criticism in the following areas:

- Intentionalist historians such as Andreas Hillgruber, Eberhard Jäckel, Klaus Hildebrand and Karl Dietrich Bracher have criticized Mommsen for underestimating the importance of Hitler and Nazi ideology. The Swiss historian Walter Hofer accused Mommsen of "not seeing because he does not want to see" what Hofer saw as the obvious connection between what Hitler wrote in Mein Kampf and his later actions.[12]

- Along the same lines, these historians criticized Mommsen for focusing too much on initiatives coming from below in the ranks of the German bureaucracy and not enough on initiatives coming from above in the leadership in Berlin.

- Mommsen's friend Yehuda Bauer has criticized Mommsen for stressing too much the similarities in values between the traditional German state bureaucracy and the Nazi Party's bureaucracy, while paying insufficient attention to the differences.

The Israeli historian Omer Bartov wrote in 2003 about Mommsen’s functionalist understanding of the Third Reich that:

"In this reading, ideology is recognized and then dismissed as irrelevant; the suffering of the victims is readily acknowledged and then omitted as having nothing to tell us about the mechanics of genocide; and individual perpetrators from Adolf Hitler, Heinrich Himmler and Reinhard Heyrdrich to the lowliest SS man are shoved out of the historical picture as contemptible, but ultimately unimportant pawns in the larger scheme of a “polycratic state” whose predilection for “cumulative radicalization” was a function of its structure rather the product of intentional planning or self-proclaimed will”[13]

The Historikerstreit

In the Historikerstreit debate, Mommsen argued that the Holocaust was a uniquely evil event which should not be compared with the other horrors of the 20th century. In an essay entitled "The Search for the ‘Lost History” Observations on the Historical Self-Evidence of the Federal Republic” first published in the September/October 1986 edition of Merkur magazine, Mommsen began his article by arguing that the Historikerstreit was the result of the desire of the German Right to have a history that they could approve of.[14] Mommsen accused Ernst Nolte of attempting to "relativize" Nazi crimes within the broader framework of the 20th century.[15] Mommsen argued that by describing Lenin's Red Terror in Russia as an "Asiatic deed" threatening Germany that Nolte was claiming that all actions directed against Communism, no matter how morally repugnant were justified by necessity.[15] Mommsen argued that all theories of totalitarianism were meant by the right for the "bracketing out" of Nazi Germany from German history, and to put down the left.[16] Mommsen argued that totalitarianism theories were meant to minimize, if not outright ignore the support of traditional German elites for the Nazi dictatorship and to allow everything that happened under the Third Reich to be blamed on Hitler.[17] Mommsen claimed that the German right was floundering due to contradictory pressures of being opposed to East Germany while seeking to champion German reunification.[18] In Mommsen’s view, conservative historians worked to write:

“…the history of the Third Reich was stylized as a fated doom from which there was no escape and from which no concrete political impulses could reach the present. Similarly the conservative historians reacted to the persecution of the Jews and to the Holocaust primarily with moral shock, leaving the events, only inadequately reconstructed by the West German research community, on the level of a purely traumatic experience”.[19]

Mommsen argued that the Historikerstreit was caused because German rightists could no longer "bracket out" National Socialism and the Holocaust from German history, thus leading to attempts by Ernst Nolte to "relativize" Nazi crimes.[20] In addition, Mommsen charged that the American Ambassador, Richard R. Burt with promoting efforts to white-wash the German past in order that West Germany could play a more effective role in the Cold War.[21] Mommsen argued that the growth in pacifist feeling in the Federal Republic as reflected in widespread public opposition to the American raid on Libya in April 1986 made it imperative for the Americans and the West German government to promote a more nationalistic version of German history, and that was what was behind the Historikerstreit.[22] Mommsen wrote that the two museums in Berlin and Bonn proposed by the government of Helmut Kohl were meant to revival traditional German authoritarianism.[23] Mommsen wrote:

“The extensive repression of nationalistic resentment, which has led to a normalization of the relationship with the neighboring peoples and even has reduced xenophobia, is being described from the conservative side as a potential danger to political stability and as a putative “loss of identity”. However, it is not primarily national feelings, but rather examples of a politics of self-interest that give neoconservatives like Michael Stürmer reason to ponder that the loss of religious bonds, only “nation and patriotism” are able to provide a consensus that transcends social classes”.[24]

Mommsen wrote that Michael Stürmer's attempts to create a national consensus on a version of German history that all Germans could take pride in was a reflection that the German rightists could not stomach modern German history, and was now looking to create a version of the German past that German rightists could enjoy.[25] Mommsen charged that to find the "lost history", Stürmer was working towards "relativizing" Nazi crimes to give Germans a history they could be proud of.[26] However, Mommsen argued that even modern right-wing German historians might have difficulty with Stürmer's "technocratic instrumentalization" of German history, which Mommsen claimed was Stürmer's way of "relativizing" Nazi crimes.[26]

In another essay entitled "The New Historical Consciousness and the Relativizing of National Socialism" first published in the October 1986 edition of the Blätter für deutsche und internationale Politik magazine, Mommsen attacked conservative historians such as Klaus Hildebrand who argued that the "singularity" of the Holocaust disproved any theory of generic fascism, while at the same time comparing National Socialism to Communism.[27] Mommsen argued that attempts by Nolte to "relativize" Nazi crimes had been going on for a long time, and had only now attracted attention with Jürgen Habermas's attack on Nolte.[27] Writing of Klaus Hildebrand's attack on Habermas, Mommsen declared:

“Hildebrand’s partisan shots can be easily deflected; that Habermas is accused of a “loss of reality and Manichaeanism”, and that his honesty is denied is witness to the self-consciousness of a self-nominated historian elite, which has set itself the task of tracing the outlines of the seeming badly needed image of history”.[28]

Writing of Hildebrand's support for Nolte, Mommsen declared that: "Hildebrand’s polemic clearly suggests that he barely considered the consequences of making Nolte’s constructs the centrepiece of a modern German conservatism that is very anxious to relativize the National Socialist experience and to find the way back to a putative historically "normal situation".[29] Mommsen described the Historikerstreit as:

“What is happening now is much like freeing lines of thought that until then had been repressed because they seemed politically questionable. These lines of thought include equating the Holocaust with resettlement [Mommsen is referring to the expulsion of Germans from Eastern Europe here]; calling into question the purposefulness of the assassination attempt of July 20, 1944, in face of the threat from the Red Army, shifting German responsibility for the Second World War and Auschwitz to the British politics of appeasement and its pacifistic practitioners; the notion that Weimar had failed primarily because of the bonds of the peace treaty, the “edict” of Versailles, the notion that the nonexistent national consciousness of the Germans was also a consequence of postwar reeducation, and the notion that in the last analysis it was the Communists who (along with the National Socialists) had buried the republican system”.[30]

Mommsen wrote about Nolte's claims of a "causal nexus" between the Gulag Archipelago and the Nazi death camps:

"In light of these questions, which thinking people encountered repeatedly, it seems superficial and insincere to narrow the discussion to the question brought up by Ernst Nolte about the extent of the similarities between the National-Socialist mass murder and the Gulag Archipelago”.[31]

Mommsen wrote that Joachim Fest was trying to advance the agenda of the German right through his attacks on Habermas for his criticism of Nolte.[32] Mommsen attacked Fest for in his view subordinating history to his right-wing politics in his defence of Nolte[33] Mommsen accused Fest of simply ignoring the real issues about the Holocaust such as the "psychological and institutional mechanisms" that explain why the German people accepted the Shoah by accepting Nolte's claim of a "casual nexus" between Communism and fascism.[34]

Mommsen declared that the Holocaust like all historical events were "singular", and that:

“It is therefore equally justified to interpret National Socialism as a specific form of fascism as it is to compare it with Communist regimes. The question is rather whether correct or misleading conclusions are drawn from the comparison”.[35]

Mommsen declared that because Germany was an advanced nation, the Holocaust was "singular", and that:

"To accept with resignation the acts of screaming injustice and to psychologically repress their social prerequisites by calling attention to similar events elsewhere and putting the blame on the Bolshevist world threat recalls the thought patterns that made it possible to implement genocide”.[36]

Mommsen called Nolte's claim of a "causal nexus" between National Socialism and Communism "...not simply methodologically untenable, but also absurd in it premises and conclusions".[37] Mommsen wrote in his opinion that Nolte's use of the Nazi era phrase "Asiatic hordes" to describe Red Army soldiers, and his use of the word "Asia" as a byword for all that is horrible and cruel in the world reflected anti-Asian racism.[38] Mommsen argued the identification of Jews with Communism that characterized the thinking of the German right between the wars had already started well before the Russian Revolution.[39] Mommsen wrote:

"In contrast to these irrefutable conditioning factors, Nolte’s derivation based on personalities and the history of ideas seems artificial, even for the explanation of Hitler’s anti-semitism…If one emphasizes the indisputably important connection in isolation, one should not then force a connection with Hitler's weltanschauung [worldview], which was in no ways original itself, in order to deprive from it the existence of Auschwitz. The battle line between the political right in Germany and the Bolsheviks had achieved its aggressive contour before Stalinism employed methods that led to deaths of millions of people. Thoughts about the extermination of the Jews had long been current, and not only for Hitler and his satraps. Many of these found their way to the NSDAP from the Deutschvölkisch Schutz-und Trutzbund [German Racial Union for Protection and Defiance], which itself had been called into life by the Pan-German Union. Hitler's step from verbal anti-semitism to practical implementation would then have happened without knowledge of and in reaction to the atrocities of the Stalinists. And thus one would have to overturn Nolte's construct, for which he cannot bring biographical evidence to bear. As a Hitler biographer, Fest distanced himself from this kind of one-sidedness by making reference to "the Austrian-German Hitler's earlier fears of and phantasies of being overwhelmed". It is not completely consistent that Fest admits that the reports of the terrorist methods of the Bolsheviks had given Hitler's "extermination complexes" a "real background". Basically, Nolte's proposal in its one-sidedness is not very helpful for explaining or evaluating what happened. The anti-Bolshevism garnished with anti-semitism had the effect, in particular for the dominant elites, and certainly not just the National Socialists, that Hitler’s program of racial annihilation met with no serious resistance. The leadership of the Wehrmacht rather willingly made themselves into accomplices in the policy of extermination. It did this by generating the “criminal orders” and implementing them. By no means did they merely passively support the implementation of their concept, although there was a certain reluctance for reasons of military discipline and a few isolated protests. To construct a “casual nexus” over all this amounts in fact to steering away from the decisive responsibility of the military leadership and the bureaucratic elites”.[40]

In the same essay, Mommsen argued that Stürmer's assertion that he who controls the past also controls the future, his work as a co-editor with the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung newspaper which had been publishing articles by Ernst Nolte and Joachim Fest denying the "singularity" of the Holocaust, and his work as an advisor to Chancellor Kohl should cause "concern" with historians.[28] Mommsen attacked Fest for his arguments for moral equating fascist crimes with Communist ones.[41] Mommsen ended his essay that the historians like Nolte, Fest, Hildebrand, and Stürmer were tying to "repress" the memory of Nazi crimes.[42]

In another essay entitled "Reappraisal and Repression The Third Reich In West German Historical Consciousness", Mommsen wrote:

"Nolte's superficial approach which associates things that do not belong together, substitutes analogies for casual arguments, and-thanks to his taste for exaggeration-produces a long outdated interpretation of the Third Reich as the result of a single factor. His claims are regarded in professional circles as a stimulating challenge at best, hardly as a convincing contribution to an understanding of the crisis of twentieth-century capitalist society in Europe. The fact that Nolte has found eloquent supporters both inside and outside the historical profession has little to do with the normal process of research and much to do with the political implications of the relativization of the Holocaust that he has insistently championed for so long...The fundamentally apologetic character of Nolte's argument shines through most clearly when he concedes Hitler's right to deport, though not to exterminate, the Jews in response to the supposed "declaration of war" issued by the World Jewish Congress; or when he claims that the activities of the SS Einsatzgruppen can be justified, at least subjectively, as operations aimed against partisans fighting the German Army".[43]

Later in his 1987 book, Auf der Suche nach historischer Normalität (In Search of Historical Normacly), Mommsen argued against attempts to "close the books" on the Nazi period.[1] Mommsen argued that the purpose of historians is not to provide a "usable' version of the German past, but instead to engage in a never-ending dialogue between past and present to create the groundwork for a more positive German national identity.[1] Mommsen was later in a book review in 1988 to call Nolte's book, Der Europäische Bürgrkrieg a "regression back to the brew of racist-nationalistic ideology of the interwar period".[44]

Other historical work

Mommsen has written highly regarded books and essays on the fall of the Weimar Republic, blaming the downfall of the Republic on German conservatives.[1] Like his brother Wolfgang, Mommsen is a champion of the Sonderweg (Special Path) interpretation of German history that sees the ways German society, culture and politics developed in the 19th century as having made the emergence of Nazi Germany in the 20th century virtually inevitable.

Another area of interest for Mommsen is dissent, opposition and resistance in the Third Reich.[1] Much of Mommsen's work in this area concerns the problems of "resistance without the people". Mommsen has drawn unfavorable comparisons between what he sees as conservative opposition and Social Democratic and Communist resistance to the Nazis. Mommsen is also an expert on social history and often writes about working-class life in the Weimar and Nazi eras.[1]

Starting in the 1960s, Mommsen was one of a younger generation of West German historians who provide a more critical assessment of Widerstand within German elites, and came to decry the "monumentalization" typical of German historical writing about Widerstand in the 1950s.[45] In two articles published in 1966, Mommsen proved the claim often advanced in the 1950s that the ideas behind "men of July 20" were the inspiration for the 1949 Basic Law of the Federal Republic was false,[46] Mommsen showed that the ideas of national-conservative opponents of the Nazis had their origins in the anti-Weimar right of the 1920s, that the system the national-conservatives wished to build in place of Nazism was not a democracy, and that national-conservatives wished to see a "Greater Germany" ruling over much of Central and Eastern Europe.[47] In the debate about what to define as resistance, Mommsen, has cautioned against the use of overtly rigid terminology, and spoke of a wide type of "resistance practice" (Widerstandspraxis), by which he meant that there were different types and forms of resistance, and that resistance should be considered a "process", in which individuals came to increasing reject the Nazi system in its entirety.[48] As an example of resistance as a "process", Mommsen used the example of Carl Friedrich Goerdeler, who initially supported the Nazis, became increasing disillusioned over Nazi economic policies while serving as Price Commissioner in the mid-1930s, and by the late 1930s was committed to Hitler's overthrow.[48] Mommsen described national-conservative resistance as "a resistance of servants of the state", who over a period of time came to gradually abandoned their former support of the regime, and instead steadily came to accept that the only way of bringing about fundamental change was to seek the regime’s destruction.[49]

The "Goldhagen Controversy"

During the "Goldhagen Controversy" of 1996, Mommsen emerged as one of Daniel Goldhagen's leading opponents, and often debated Goldhagen on German TV.[50] Mommsen's friend, the British historian Sir Ian Kershaw wrote he thought that Mommsen had "destroyed" Goldhagen during their debates over Goldhagen's book Hitler's Willing Executioners.[50] In a 1997 interview, Mommsen was quoted as saying about Goldhagen that:

"Goldhagen does not understand much about the antisemitic movements in the nineteenth century. He only addresses the impact antisemitism had on the masses in Germany, especially in the Weimar period, which is quite problematic...He [Goldhagen] did not say that explicitly, but he construes an unlinear continuity of German antisemitism from the medieval period onwards, and he argues that Hitler was the result of German antisemitism. This, however, and similar suggestions are quite wrong, because Hitler's seizure of power was not due to any significant impact of his antisemitic propaganda at that time. Obviously, antisemitism did not play a significant role in the election campaigns between September 1930 and November 1932. Goldhagen just ignores this crucial phenomenon. Besides that, Goldhagen, while talking all the time about German antisemitism, omits the specific impact of the völkisch antisemitism as proclaimed by Houston Stuart Chamberlain and the Richard Wagner movement which directly influenced Hitler as well as the Nazi party. He does not have any understanding of the diversities within German antisemitism, and he does not know very much about the internal structure of the Third Reich either. For instance, he claims that the Jews lost their German citizenship by the Nuremberg laws, while actually this was due to Hans Globke's collaboration with Martin Bormann in changing the citizenship legislation late in 1938.".[51]

The "diversities" of German anti-semitism Mommsen spoken of were defined by him in the same interview as:

"One should differentiate between the cultural antisemitism symptomatic of the German conservatives — found especially in the German officer corps and the high civil administration — and mainly directed against the Eastern Jews on the one hand, and völkisch antisemitism on the other. The conservative variety functions, as Shulamit Volkov has pointed out, as something of a “cultural code.” This variety of German antisemitism later on played a significant role insofar as it prevented the functional elite from distancing itself from the repercussions of racial antisemitism. Thus, there was almost no relevant protest against the Jewish persecution on the part of the generals or the leading groups within the Reich government. This is especially true with respect to Hitler's proclamation of the “racial annihilation war” against the Soviet Union.

Besides conservative antisemitism, there existed in Germany a rather silent anti-Judaism within the Catholic Church, which had a certain impact on immunising the Catholic population against the escalating persecution. The famous protest of the Catholic Church against the euthanasia program was, therefore, not accompanied by any protest against the Holocaust.

The third and most vitriolic variety of antisemitism in Germany (and elsewhere) is the so-called völkisch antisemitism or racism, and this is the foremost advocate of using violence. Anyhow, one has to be aware that even Hitler until 1938 and possibly 1939 still relied on enforced emigration to get rid of German Jewry; and there did not yet exist any clear-cut concept of killing them. This, however, does not mean that the Nazis elsewhere on all levels did not hesitate to use violent methods, and the inroads against Jews, Jewish shops, and institutions show that very clearly. But there did not exist any formal annihilation program until the second year of the war. It came into being after the “reservation” projects had failed. That, however, does not mean that those methods did not include a lethal component."[51]

In the same interview, Mommsen advanced a functionalist understanding of how the Holocaust occurred,

"Undeniably, there existed a consensus about getting rid of the Jews. But it was a different question whether to kill them or to press them to leave the country. Actually, with respect to this question the Nazi regime moved into an impasse, because the enforced emigration was surpassed by the extension of the area of German power. There did not exist any clear-cut concept until 1941. The process of cumulative radicalization of the anti-Jewish measures sprang up from a self-induced production of emergency situations which nurtured the process.

At a later stage, the perpetrators got adjusted to murdering people and did not reflect about it any longer. Where the SS cadres were concerned, they were certainly driven by racist prejudice and national fanaticism. But other factors contributed to the escalation of violence. The German scholar Götz Aly, for instance, showed very clearly that among the adjacent motivations, the program to resettle the Volk Germans [Mommsen is referring to the Volksdeutsche here] who came from the Baltic states and from Volhynia, later on from Bessarabia, too, played a significant role. The resettlement program functioned as an indispensable impetus to intensify the deportation and ultimately the liquidation of the Jews living in the annexed parts of Poland and the Generalgouvernement.

There existed an interaction between the target of resettling the Volk Germans in order to create the Great German Reich and the elimination of the Jews in Eastern and Central Europe. The leading perpetrators like Adolf Eichmann or Odilo Globocnik originally spent about 80 percent of their work on resettlement issues and only 10 percent on the “Jewish Question.” Thus, the job of implementing the Holocaust appears to be rather “unpleasant,” but forms an inseparable part of building the Great German Reich in the East. As could be expected from the very start, after the resettlement initiatives failed almost completely, the liquidation of the Jews became something like a compensatory task and the implementation of the Holocaust was finally all that was performed of the far more comprehensive program of ethnic cleansing and re-ordering of the east.[51]

Later work

In an August 2000 book review, Mommsen called Norman Finkelstein's book The Holocaust Industry "a most trivial book, which appeals to easily aroused anti-Semitic prejudices."[52]

A major figure in his home country, Mommsen often took stands on the great issues of the day, believing that the responsibility for ensuring the mistakes of the past are never repeated rests upon an engaged and historically-conscious citizenry.[1] Mommsen saw it as the duty of the historian to constantly critique contemporary society.[1]

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Menke, Martin "Mommsen, Hans" pages 826–827 from The Encyclopedia of Historians and Historical Writing edited by Kelly Boyd, Volume 2, London: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishing, 1999 page 826

- ↑ Hans Mommsen, historian - obituary

- 1 2 3 Marrus, Michael The Holocaust In History, Toronto: Key Porter, 2000 page 42

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Kershaw, Ian The Nazi Dictatorship London : Arnold 2000 page 99

- 1 2 Kershaw, Ian The Nazi Dictatorship London : Arnold 2000 page 70

- ↑ Kershaw, Ian The Nazi Dictatorship London : Arnold 2000 page 37

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Kershaw, Ian The Nazi Dictatorship London : Arnold 2000 page 77

- ↑ Kershaw, Ian The Nazi Dictatorship London : Arnold 2000 pages 77–78

- 1 2 Kershaw, Ian The Nazi Dictatorship London : Arnold 2000 page 78

- 1 2 Kershaw, Ian The Nazi Dictatorship London : Arnold 2000 page 138

- 1 2 Kershaw, Ian The Nazi Dictatorship London : Arnold 2000 page 139

- ↑ Kershaw, Ian The Nazi Dictatorship London : Arnold 2000 page 98

- ↑ Bartov, Omer Germany's War and the Holocaust: Disputed Histories, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2003 page 81

- ↑ Mommsen, Hans "The Search for the 'Lost History'" pages 101–113 from Forever In The Shadow of Hitler? edited by Ernst Piper, Humanities Press, Atlantic Highlands, 1993 pages 101–102

- 1 2 Mommsen, Hans "The Search for the 'Lost History'" pages 101–113 from Forever In The Shadow of Hitler? edited by Ernst Piper, Humanities Press, Atlantic Highlands, 1993 page 108

- ↑ Mommsen, Hans "The Search for the 'Lost History'" pages 101–113 from Forever In The Shadow of Hitler? edited by Ernst Piper, Humanities Press, Atlantic Highlands, 1993 page 103

- ↑ Mommsen, Hans "The Search for the 'Lost History'" pages 101–113 from Forever In The Shadow of Hitler? edited by Ernst Piper, Humanities Press, Atlantic Highlands, 1993 pages 106–107

- ↑ Mommsen, Hans "The Search for the 'Lost History'" pages 101–113 from Forever In The Shadow of Hitler? edited by Ernst Piper, Humanities Press, Atlantic Highlands, 1993 pages 104–105

- ↑ Mommsen, Hans "The Search for the 'Lost History'" pages 101–113 from Forever In The Shadow of Hitler? edited by Ernst Piper, Humanities Press, Atlantic Highlands, 1993 pages 107

- ↑ Mommsen, Hans "The Search for the 'Lost History'" pages 101–113 from Forever In The Shadow of Hitler? edited by Ernst Piper, Humanities Press, Atlantic Highlands, 1993 pages 108

- ↑ Mommsen, Hans "The Search for the 'Lost History'" pages 101–113 from Forever In The Shadow of Hitler? edited by Ernst Piper, Humanities Press, Atlantic Highlands, 1993 pages 108–109

- ↑ Mommsen, Hans "The Search for the 'Lost History'" pages 101–113 from Forever In The Shadow of Hitler? edited by Ernst Piper, Humanities Press, Atlantic Highlands, 1993 pages 110–111

- ↑ Mommsen, Hans "The Search for the 'Lost History'" pages 101–113 from Forever In The Shadow of Hitler? edited by Ernst Piper, Humanities Press, Atlantic Highlands, 1993 pages 111–112

- ↑ Mommsen, Hans "The Search for the 'Lost History'" pages 101–113 from Forever In The Shadow of Hitler? edited by Ernst Piper, Humanities Press, Atlantic Highlands, 1993 pages 111

- ↑ Mommsen, Hans "The Search for the 'Lost History'" pages 101–113 from Forever In The Shadow of Hitler? edited by Ernst Piper, Humanities Press, Atlantic Highlands, 1993 page 101.

- 1 2 Mommsen, Hans "The Search for the 'Lost History'" pages 101–113 from Forever In The Shadow of Hitler? edited by Ernst Piper, Humanities Press, Atlantic Highlands, 1993 page 109

- 1 2 Mommsen, Hans "The New Historical Consciousness" pages 114–124 from Forever In The Shadow of Hitler? edited by Ernst Piper, Humanities Press, Atlantic Highlands, 1993 page 114

- 1 2 Mommsen, Hans "The New Historical Consciousness" pages 114–124 from Forever In The Shadow of Hitler? edited by Ernst Piper, Humanities Press, Atlantic Highlands, 1993 page 115

- ↑ Mommsen, Hans "The New Historical Consciousness" pages 114–124 from Forever In The Shadow of Hitler? edited by Ernst Piper, Humanities Press, Atlantic Highlands, 1993 page 123

- ↑ Mommsen, Hans "The New Historical Consciousness" pages 114–124 from Forever In The Shadow of Hitler? edited by Ernst Piper, Humanities Press, Atlantic Highlands, 1993 pages 115–116

- ↑ Mommsen, Hans "The New Historical Consciousness" pages 114–124 from Forever In The Shadow of Hitler? edited by Ernst Piper, Humanities Press, Atlantic Highlands, 1993 page 119

- ↑ Mommsen, Hans "The New Historical Consciousness" pages 114–124 from Forever In The Shadow of Hitler? edited by Ernst Piper, Humanities Press, Atlantic Highlands, 1993 pages 116–117

- ↑ Mommsen, Hans "The New Historical Consciousness" pages 114-124 from Forever In The Shadow of Hitler? edited by Ernst Piper, Humanities Press, Atlantic Highlands, 1993 pages 117.

- ↑ Mommsen, Hans "The New Historical Consciousness" pages 114-124 from Forever In The Shadow of Hitler? edited by Ernst Piper, Humanities Press, Atlantic Highlands, 1993 pages 119-120.

- ↑ Mommsen, Hans "The New Historical Consciousness" pages 114–124 from Forever In The Shadow of Hitler? edited by Ernst Piper, Humanities Press, Atlantic Highlands, 1993 page 117

- ↑ Mommsen, Hans "The New Historical Consciousness" pages 114–124 from Forever In The Shadow of Hitler? edited by Ernst Piper, Humanities Press, Atlantic Highlands, 1993 page 118

- ↑ Mommsen, Hans "The New Historical Consciousness" pages 114–124 from Forever In The Shadow of Hitler? edited by Ernst Piper, Humanities Press, Atlantic Highlands, 1993 page 120

- ↑ Mommsen, Hans "The New Historical Consciousness" pages 114–124 from Forever In The Shadow of Hitler? edited by Ernst Piper, Humanities Press, Atlantic Highlands, 1993 page 122

- ↑ Mommsen, Hans "The New Historical Consciousness" pages 114–124 from Forever In The Shadow of Hitler? edited by Ernst Piper, Humanities Press, Atlantic Highlands, 1993 page120

- ↑ Mommsen, Hans "The New Historical Consciousness" pages 114–124 from Forever In The Shadow of Hitler? edited by Ernst Piper, Humanities Press, Atlantic Highlands, 1993 pages 120–121

- ↑ Mommsen, Hans "The New Historical Consciousness" pages 114–124 from Forever In The Shadow of Hitler? edited by Ernst Piper, Humanities Press, Atlantic Highlands, 1993 pages 121–122

- ↑ Mommsen, Hans "The New Historical Consciousness" pages 114–124 from Forever In The Shadow of Hitler? edited by Ernst Piper, Humanities Press, Atlantic Highlands, 1993 pages 123–124

- ↑ Mommsen, Hans "Reappraisal and Repression" pages 173-184 from Reworking the Past edited by Peter Baldwin, Beacon Press: Boston, 1990 pages 178-179

- ↑ Mommsen, Hans "Das Ressentiment Als Wissenschaft: Ammerkungen zu Ernst Nolte’s Der Europäische Bürgrkrieg 1917–1945: Nationalsozialimus und Bolschewismus" pages 495–512 from Geschichte und Gesellschaft, Volume 14, Issue # 4 1988 page 512.

- ↑ Kershaw, Ian The Nazi Dictatorship Problems and Perspectives of Interpretation, London: Arnold Press, 2000 pages 187–188

- ↑ Kershaw, Ian The Nazi Dictatorship Problems and Perspectives of Interpretation, London: Arnold Press, 2000 page 188

- ↑ Kershaw, Ian The Nazi Dictatorship Problems and Perspectives of Interpretation, London: Arnold Press, 2000 pages 188–189

- 1 2 Kershaw, Ian The Nazi Dictatorship Problems and Perspectives of Interpretation, London: Arnold Press, 2000 page 196

- ↑ Kershaw, Ian The Nazi Dictatorship Problems and Perspectives of Interpretation, London: Arnold Press, 2000 page 197

- 1 2 Kershaw, Ian The Nazi Dictatorship: Problems & Perspectives of Interpretation, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000 page 254

- 1 2 3 Mommsen, Hans (December 12, 1997). "Interview with Hans Mommsen" (PDF). Yad Vashem. Retrieved 2010-02-06.

- ↑ http://www.normanfinkelstein.com/article.php?PG=3&AR=11

Work

- Die Sozialdemokratie und die Nationalitätenfrage im habsburgischen Vielvölkerstaat (Social Democracy and the Nationalities Question in the Multi-Ethnic Hapbsburg Empire), 1963.

- "Der Reichstagsbrand und seine politischen Folgen," in Vierteljahrshefte fur Zeitgeschichte, Volume 12, 1964, pages 351–413 (The Reichstag Fire and Its Political Consequences), translated into English as "The Reichstag Fire and Its Political Consequences" pages 129-222 from Republic to Reich The Making of the Nazi Revolution edited by Hajo Holborn, New York: Pantheon Books, 1972, ISBN 0-394-47122-9.

- Beamtentum im Dritten Reich: Mit ausgewählten Quellen zur nationalsozialistischen Beamtenpolitik (The Institution of the Civil Service in the Third Reich: With Selected Sources On National Socialist Civil Service Policy), 1966.

- Industrielles System und politische Entwicklung in der Weimarer Republik (Industrialism and Political Development of the Weimar Republic), co-edited with Dietmar Petzina and Bernd Weisbrod, 1974.

- Sozialdemokratie zwische Klassenbewegung und Volkspartei (Social Democracy Between Class Movement and Populist Party), edited by Hans Mommsen, 1974.

- "National Socialism-Continuity and Change" pages 179-210 from Fascism : A Reader's Guide : Analyses, Interpretations, Bibliography edited by Walter Laqueur, Berkeley : University of California Press, 1976, ISBN 0-520-03033-8.

- Arbeiterbewegung und Industrieller Wandel: Studien zu Gewerkschaftlichen Organisationsproblemen im Reich und an der Ruhr (Labor Movement and Industrial Change: Problems in Union Organizing in the Reich and the Ruhr), edited by Hans Mommsen, 1978.

- Klassenkampf oder Mitbestimmung: Zum Problem der Kontrolle wirtschaftlicher Macht in der Weimarer Republik (Class Struggle or Co-Determination: Issues in Controlling Economic Influence in the Weimar Republic), 1978.

- Arbeiterbewegung und Nationale Frage: Ausgewählte Aufsätze (The Labor Movement and the National Question: Selected Essays), 1979.

- Glück Auf, Kameraden! Die Bergarbeiter und ihre Organisationen in Deutschland (Good Luck, Comrades! Miners and Their Organizations in Germany), co-edited with Ulrich Borsdorf, 1979.

- Vom Elend der Handarbeit: Probleme historischer Unterschichtenforschung (Concerning the Misery of Piece-Work: Problems in Conducting Historical Research about the Underclass), co-edited with Winfried Schulze, 1981.

- Politik und Gesellschaft im alten und neuen Österreich: Festschrift für Rodolf Neck zum 60. Geburtstag (Politics and Society in the Old and New Austria: Festschrift for Rudolf Neck on the Occasion of his 60th Birthday), co-edited with Isabella Acker and Walter Hummelbergrer, 1981.

- Auf der Suche nach historischer Normalität: Beiträge zum Geschichtsbildstreit in der Bundesrepublik (In Search of Historical Normalcy), 1987.

- Herrschaftsalltag im Dritten Reich: Studien und Texte (Everyday Rule in the Third Reich: Studies and Texts), co-edited with Susanne Willems, 1988.

- Die verspielte Freiheit: Der Weg der Republik von Weimar in den Untergang, 1918 bis 1933, 1989; translated into English by Elborg Forster & Larry Eugene Jones as The Rise And Fall Of Weimar Democracy, Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, 1996, ISBN 0-8078-2249-3.

- "Reappraisal and Repression The Third Reich In West German Historical Consciousness" pages 173-184 from Reworking the Past edited by Peter Baldwin, Beacon Press: Boston, 1990, ISBN 0-8070-4302-8.

- Der Nationalsozialismus und die deutsche Gesellschaft, 1991; translated by Philip O'Connor into English as From Weimar to Auschwitz, Princeton, N.J. : Princeton University Press, 1991, ISBN 0-691-03198-3 .

- "The German Resistance against Hitler and the Restoration of Politics," Journal of Modern History Vol. 64, December 1992.

- "The Search for the 'Lost History' Observations on the Historical Self-Evidence of the Federal Republic" pages 101–113 and "The New Historical Consciousness and the Relativizing of National Socialism" pages 114–124 from Forever In The Shadow of Hitler? edited by Ernst Piper, Humanities Press, Atlantic Highlands, 1993, ISBN 0-391-03784-6.

- "Reflections on the Position of Hitler and Göring in the Third Reich" pages 86–97 from Reevaluating the Third Reich edited by Jane Caplan and Thomas Childers, New York, 1993, ISBN 0-8419-1178-9.

- Der Nationalsozialismus: Studien zur Ideologie und Herrschaft (Studies in National Socialist Ideology and Rule), co-edited with Wolfgang Benz and Hans Buchheim, 1993.

- Ungleiche Nachbarn: Demokratische und Nationale Emanzipation bei Deutsche, Tschechen und Slowaken (1815–1914) (Unequal Neighbours: Democratic and National Emancipation of the Germans, Czechs, and Slovaks, 1815–1914) co-edited with Jiřǐ Kořalka, 1993.

- "Adolf Hitler und der 9. November 1923" (Adolf Hitler and 9 November 1923) from Der 9. November: Fünf Essays zur deutschen Geschichte, 1994.

- Widerstand und politische Kultur in Deutschland und Österreich (Resistance and Political Culture in Germany and Austria), 1994.

- "Der Antisemitismus war eine notwendige, aber keineswegs hinreichende Bedingung für den Holocaust" in Die Zeit, Nr. 36, 30 August 1996, translated into English as "Conditions for Carrying Out the Holocaust: Comments on Daniel Goldhagen's Book" pages 31–43 from Hyping the Holocaust: Scholars Answer Goldhagen edited by Franklin Littell, East Rockaway, NY: Cummings & Hathaway, 1997, ISBN 0-943025-98-2

- Der Erste Weltkrieg und die europäische Nachkriegsordnung: Sozialer Wandel und Formveränderung der Politik, ed. by Hans Mommsen, 2000.

- Alternative zu Hitler. Studien zur Geschichte des deutschen Widerstandes, 2000; translated into English by Angus McGeoch as Alternatives to Hitler : German Resistance under the Third Reich, Princeton : Princeton University Press, 2003, ISBN 0-691-11693-8.

- Von Weimar nach Auschwitz: Zur Geschichte Deutschlands in der Weltkriegsepoche, 2001.

- The Third Reich Between Vision And Reality: New perspectives on German history, 1918–1945, ed. by Hans Mommsen, 2001, ISBN 978-1-85973-254-0.

- Germans Against Hitler: The Stauffenberg Plot and Resistance Under the Third Reich, translated into English by Angus McGeoch, London: I. B. Tauris, 2009, ISBN 1-84511-852-9.

- Das NS-Regime und die Auslöschung des Judentums in Europa (The Nazi Regime and the Extermination of the Jews in Europe), Göttingen: Wallstein-Verlag, 2014, ISBN 978-3-8353-1395-8.

See also

References

- Bauer, Yehuda Rethinking the Holocaust, New Haven Conn.; London : Yale University Press, 2001.

- "Einleitung" (Introduction) in Der Nationalsozialismus und die deutsche Geselleschaft: Ausgewählte Aufsätze (National Socialism and German Society: Selected Essays) edited by Lutz Niethammer and Bernd Wiesbrod, Reinbek: Rowoht, 1991.

- Von der Aufgabe der Freiheit: politische Antwortung und bürgerliche Gesellschaft im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert: Festschrift für Hans Mommsen zum. 5. November 1995 (The Task of Freedom: Political Responsibility and Civil Society in the 19th and 20th centuries) edited by Christian Jansen, Lutz Niethammer, and Bernd Wiesbrod, Berlin: Akademie, 1995.

- Kautz, Fred The German Historians: Hitler’s Willing Executioners and Daniel Goldhagen, Montreal: Black Rose Books, 2003, ISBN 1-55164-213-1.

- Kershaw, Ian The Nazi Dictatorship : problems and perspectives of interpretation London : Arnold ; New York : Copublished in the USA by Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Menke, Martin "Mommsen, Hans" pages 826-827 from The Encyclopedia of Historians and Historical Writing edited by Kelly Boyd, Volume 2, London: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishing, 1999.

- Marrus, Michael The Holocaust in History, Toronto : Lester & Orpen Dennys, 1987.

- Hans Schneider: Neues vom Reichstagsbrand – Eine Dokumentation. Ein Versäumnis der deutschen Geschichtsschreibung. Mit einem Geleitwort von Iring Fetscher und Beiträgen von Dieter Deiseroth, Hersch Fischler, Wolf-Dieter Narr; herausgegeben von der Vereinigung Deutscher Wissenschaftler e. V., Berlin : Berliner Wissenschafts-Verlag, 2004, ISBN 3-8305-0915-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hans Mommsen. |

- The Genesis of the Holocaust: An Assessment of the Functionalist School of Historiography, Jacqueline Bird

- Portrait of Hans Mommsen

- An Interview with Professor Hans Mommsen