Hara hachi bun me

Hara hachi bun me (腹八分目/はらはちぶんめ),[1] (or hara hachi bu, and sometimes misspelled hari hachi bu), is a Confucian[2] teaching that instructs people to eat until they are 80 percent full.[3] Roughly, in English the Japanese phrase translates to, “Eat until you are eight parts (out of ten) full”[3] or “belly 80 percent full”.[4]

Okinawans

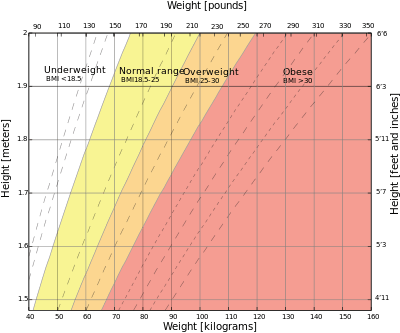

As of the early 21st century, Okinawans in Japan, through practicing hara hachi bu, are the only human population to have a self-imposed habit of calorie restriction.[3] They consume about 1,800[4] to 1,900 kilo-calories per day.[5] Their elders' typical body mass index (BMI) is about 18 to 22, compared to a typical BMI of 26 or 27 for adults over 60 in the United States.[6] Okinawa has the world's highest proportion of centenarians, at approximately 50 per 100,000 people.[7]

Biochemist Clive McCay, a professor at Cornell University in the 1930s, reported that significant calorie restriction prolonged life in laboratory animals.[8][9] Authors Bradley and Craig Wilcox and Makoto Suzuke believe that hara hachi bu may act as a form of calorie restriction, thus extending practitioners' life expectancy. They believe hara hachi bun me assists in keeping the average Okinawan's BMI low, and this is thought to be due to the delay in the stomach stretch receptors that help signal satiety. The result of not practising hara hachi bun me is a constant stretching of the stomach which in turn increases the amount of food needed to feel full.[3]

Influence

In the 1965 book Three Pillars of Zen, the author quotes Hakuun Yasutani in his lecture for zazen beginners as telling his students about the book Zazen Yojinki (Precautions to Observe in Zazen), written circa 1300, which advises practitioners to eat about two-thirds of their capacity. Yasutani advises his students to eat only eighty percent of their capacity, and he repeats a Japanese proverb: “eight parts of a full stomach sustain the man; the other two sustain the doctor”.[10]

Hara hachi bun me was popularized in the United States by a variety of modern books on diet and longevity.[11][12][13]

See also

References

- Buettner, Dan (2008). The Blue Zones. National Geographic Society. ISBN 978-1-4262-0274-2.

Footnotes

- ↑ "Jisho.org online Japanese-English dictionary". jisho.org. 2015. Retrieved 2015-07-02.

- ↑ Buettner, pp. 7, 227

- 1 2 3 4 Willcox BJ; Willcox DC; Suzuki M (2002). The Okinawa Program : How the World's Longest-Lived People Achieve Everlasting Health And How You Can Too. Three Rivers Press. pp. 86–87. ISBN 978-0-609-80750-7.

- 1 2 Grossman, Terry (2005). "Latest advances in antiaging medicine" (PDF). The Keio Journal of Medicine. 54 (2): 85–94. doi:10.2302/kjm.54.85.

- ↑ Beuttner, p. 233

- ↑ Smolin LA; Grosvenor MB (2004). Basic Nutrition. Infobase Publishing. p. 134. ISBN 0-7910-7850-7.

- ↑ "Okinawa's Centenarians". The Okinawa Centenarian Study. Retrieved 21 April 2013.

- ↑ Ingram, DK; et al. (2004). "Development of calorie restriction mimetics as a prolongevity strategy". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. Wiley-Blackwell. doi:10.1196/annals.1297.074.

- ↑ "Clive McCay papers, 1920-1967" (PDF). Cornell University Library. Retrieved June 1, 2011.

- ↑ Kapleau, Philip (1989). The Three pillars of Zen: teaching, practice, and enlightenment. New York: Anchor Books. pp. 43–44. ISBN 0-385-26093-8.

- ↑ Buettner, pp. 83, 96, 103, 233

- ↑ Wansink, Brian (2010). Mindless Eating: Why We Eat More Than We Think. Bantam Books. pp. 34. ISBN 0-345-52688-0.

- ↑ Beckerman, James (2011). The Flex Diet. Touchstone. pp. 162–163. ISBN 978-1-4391-5569-1.