Henry Cort

| Henry Cort | |

|---|---|

|

Henry Cort | |

| Born |

about 1740 unknown |

| Died | Friday 23 May 1800 |

| Nationality | English |

| Occupation | Inventor, pioneer in the iron industry |

| Known for | Inventions relating to puddling and rolling in the manufacture of iron. |

| Children | Richard Cort |

Henry Cort (?1741 – 23 May 1800) was an English ironmaster. During the Industrial Revolution in England, Cort began refining iron from pig iron to wrought iron (or bar iron) using innovative production systems. In 1783 he patented the puddling process for refining iron ore.

Biography

Early life

Little is known of Cort's early life other than that he was possibly born in Lancaster, England although his parents are unknown.[1] Although his date of birth is traditionally given as 1740, this can not be confirmed and his early life remains an enigma.[2] By 1765, Cort had become a Royal Navy pay agent, acting on commission collecting half pay and widows' pensions from an office in Crutched Friars near Aldgate in London. At that time, despite Abraham Darby's improvements in the smelting of iron using coke instead of charcoal as blast furnace fuel, the resultant product was still only convertible to bar iron by a laborious process of decarburisation in finery forges. As a result, bar iron imported from the Baltic undercut that produced in Britain, be imported from Russia at considerable expense.[3]

In 1768, Cort's second marriage was to Elizabeth Heysham, the daughter of a Romsey solicitor and steward of the Duke of Portland whose estates included Titchfield.[4] whose uncle William Attwick although a successful London attorney had inherited the family ironmongery business in Gosport which supplied the navy with mooring chains and other naval stores made of iron.[5]

Partnership with Samuel Jellicoe

In 1779, the Royal Navy's Victualling Commissioners agreed with Cort, who had taken over Attwick's business, to re roll iron hoops for their barrels. This led to Cort investing in a new rolling mill at Fontley in Titchfield which was later used for the production of bar iron.[6] Short of funds, he turned to Adam Jellicoe, at that time chief clerk in the pay branch of the Royal Navy, who agreed to finance Cort to the amount of nearly £30 000 on the security of the assignment of Cort's patents. As part of the arrangement Jellicoe's son Adam became a partner in the Fontley Works. The deal was later to have unfortunate repercussions for Cort[7]

Rolling mill and puddling furnace

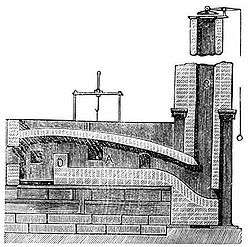

Cort developed his ideas at the Fontley Works resulting in a 1783 patent for a grooved rolling mill and a 1784 patent for his balling or puddling furnace, which allowed for the manufacture of crude, standardised shapes made of wrought iron. His work built on the existing ideas of the Cranege brothers and their reverberatory furnace (where heat is applied from above, rather than through the use of forced air from below) and Peter Onions' puddling process where iron is stirred to separate out impurities and extract the higher quality wrought iron. The furnace effectively lowered the carbon content of the cast iron charge through oxidation while the "puddler" extracted a mass of iron from the furnace using an iron "rabbling bar". The extracted ball of metal was then processed into a "shingle" by a shingling hammer, after which it was rolled in the rolling mill.

Death of Adam Jellicoe

When Adam Jellicoe died suddenly on 30 August 1789, it became apparent that the £27,000 lent to Cort had come from public funds belonging to the Royal Navy. As a result, the Crown seized the two patents Jellicoe had pledged as security, which were subsequently valued at only £100. Cort was held responsible for Jellicoe's debt and declared bankrupt.[6] The Crown gave Samuel Jellicoe possession of the works at Fontley where he " remained ... undisturbed for long years afterwards" and made no attempt to realise patent dues from ironmasters, as the system did not work with the grey iron produced in the Midlands and South Wales.[8]

Patents and royalties

The importance of Cort's improvements to the process of iron making were recognised as early as 1786 by Lord Sheffield who regarded them along with James Watt's work on the steam engine as more important than the loss of America.[9] In 1787, Cort came to an agreement with South Wales ironmaster Richard Crawshay whereby all iron manufactured according to the former's patents would result in a royalty of 10 shillings per ton.[10]

Personal life

Cort's marriage to Elizabeth Heysham produced 13 children.[11] His business ventures did not bring him wealth, even though vast numbers of the puddling furnaces that he developed were eventually used (reportedly 8,200 by 1820), they used a modified version of his process and thus avoided payment of royalties. He was later awarded a government pension, but died a ruined man, and was buried in the churchyard of St John-at-Hampstead, London.

Legacy

Fifty years after Cort's death, The Times of London lauded him as "the father of the iron trade".[12] His son, Richard Cort, became a cashier for the British Iron Company in 1825 – 6 and subsequently wrote several pamphlets severely critical of the management of the company. He also attacked a number of early railway companies.

The Henry Cort Community College bears his name and is located in the town of Fareham, in the south of Hampshire, England.

Notes

- ↑ Mott, R. A. (ed. P. Singer), Henry Cort: the Great Finer, The Metals Society, London 1983

- ↑ Evans, Chris (2006). "Cort, Henry (1741?–1800)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 5 August 2010.

- ↑ Evans, C., Jackson, O., and Ryden, G. ‘Baltic iron and the British iron industry in the eighteenth century’. Econ. Hist. Rev. (2nd ser.), 55, 642–665. 2002: King, P. ‘The production and consumption of bar iron in early modern England and Wales’ Econ. Hist. Rev. (2nd ser.), 58, 1-33. 2005:

- ↑ Espinasse (1877), p. 225

- ↑ Pam Moore. "History of Henry Cort". Fareham Borough Council. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- 1 2 Philip Eley. "The Gosport Iron Foundry and Henry Cort". Hampshire County Council. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- ↑ Espinasse (1877), p. 229.

- ↑ Espinasse (1877), p 234

- ↑ Matschoss, Conrad (June 1970). Great Engineers. Books for Libraries; Reprint edition. p. 110. ISBN 978-0836918373.

- ↑ Espinasse (1877), p. 233

- ↑ Espinasse (1877), p.225

- ↑ The Times, editorial, 29 July 1856, cited from Rosen (2010), p. 328

References

- Espinasse, Francis (1877). Lancashire Worthies. London: Simpkin Marshall, & Co.

- Rosen, William (2010). The most powerful idea in the world: a story of steam, industry, and invention. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-679-60361-0.

- Smiles, Samuel (2010). Industrial Biography: Iron Workers and Tool Makers. Europ Ischer Hochschulverlag Gmbh & Co. Kg. ISBN 978-3867414654.

Further reading

- Dickinson, H. W. Henry Cort's Bicentenary, in The Newcomen Society, Transactions 1940–41, volume XXI, 1943.

- Mott, R. A. (ed. P. Singer), Henry Cort: the Great Finer, The Metals Society, London 1983)

- Webster, Thomas The Case of Henry Cort and his Inventions in the Manufacture of British Iron, Mechanics' Magazine, 1859

External links

- Henry Cort – brief biography

- Henry Cort – another brief biography

- The Gosport Iron Foundry and Henry Cort

- Henry Cort, Father of the Iron Trade - the most reliable and up-to-date information on the British inventor