History of Waldorf schools

| Part of a series on |

| Anthroposophy |

|---|

| General |

|

Anthroposophy · Rudolf Steiner Anthroposophical Society · Goetheanum |

| Anthroposophically inspired work |

|

Waldorf education |

| Philosophy |

| The Philosophy of Freedom · Social threefolding |

This article on the History of Waldorf schools includes descriptions of the schools' historical foundations, geographical distribution and internal governance structures.

| Continent | Schools | Countries |

|---|---|---|

| Africa | 22 | 5 |

| Asia | 58 | 12 |

| Europe | 720 | 33 |

| North America | 155 | 3 |

| Oceania | 52 | 2 |

| South America | 56 | 6 |

| Total | 1063 | 62 |

The first Waldorf schools

In the chaotic circumstances of post-World War I Germany, Rudolf Steiner had been giving lectures on his ideas for a societal transformation in the direction of independence of the economic, governmental and cultural realms, known as Social Threefolding, to the workers of various factories. On April 23, 1919, he held such a lecture for the workers of the Waldorf-Astoria cigarette factory in Stuttgart, Germany; in this lecture he mentioned the need for a new kind of comprehensive school. On the following day, the workers approached Herbert Hahn, one of Steiner's close co-workers, and asked him whether their children could be given such a school. Independently of this request, the owner and managing director of the factory, Emil Molt, announced his decision to set up such a school for his factory workers' children to the company's Board of Directors and asked Steiner to be the school's pedagogical consultant. The name Waldorf thus comes from the factory which hosted the first school.[2]

The original Waldorf school was formed as an independent institution licensed by the local government as an exploratory model school with special freedoms. Steiner specified four conditions:

- that the school be open to all children;

- that it be coeducational;

- that it be a unified twelve-year school;

- that the teachers, those individuals actually in contact with the children, have primary control over the pedagogy of the school, with a minimum of interference from the state or from economic sources.

On May 13, 1919, Molt, Steiner and E.A. Karl Stockmeyer had a preliminary discussion with the Education Ministry with the aim of finding a legal structure that would allow for an independent school. Stockmeyer was then given the task of finding teachers as a foundation for the future school. At the end of August, seventeen candidates for teaching positions attended what would be the first of many pedagogical courses sponsored by the school; twelve of these candidates were chosen to be the school's first teachers. The school opened on September 7, 1919 with 256 pupils in eight grades; 191 of the pupils were from factory families, the other 65 came from interested families from Stuttgart, many of whom were already engaged in the anthroposophical movement in that city. In the following years, a numerical balance between the factory workers' and outside children was achieved; it had been an explicit goal of the social three-folding movement to create a school that bridged social classes in this way. For the first year, the school was a company school and all teachers were listed as workers at Waldorf-Astoria, by the second year the school had become an independent entity.

The Stuttgart school grew quickly, adding a grade each year of secondary education, which thus by the 1923/4 school year included grades 9-12, and adding parallel classes in all grades. By 1926 there were more than 1,000 pupils in 28 classes. Already, in 1922, Steiner had brought his educational ideas to an English-speaking audience when he delivered twelve lectures at Manchester College at the Oxford Conference[3] on the philosophy and practice of education and the imperative for a moral component.[4]

The first decade

Schools founded in the first decade after the Stuttgart school include:

- Cologne, Germany (1921) (closed 1925)

- Dornach, Switzerland (1921) – high school

- King's Langley, Hertfordshire, England (1922) where a boarding school began transitioning into a Waldorf school

- Hamburg, Germany (1922)

- Essen, Germany (1922) (closed by the Nazi government in 1936)

- The Hague, Netherlands (1923)

- London, England (1925), now Michael Hall school in Sussex, England

- Basel, Switzerland (1926)

- Oslo, Norway (1926)

- Hannover, Germany (1926)

- Budapest, Hungary (1926)

- Zurich, Switzerland (1927)

- Gloucester, England (1927)

- Berlin, Germany (1928)

- New York, USA (1928)

- Vienna, Austria (1929)

- Bergen, Norway (1929)

- Dresden, Germany (1929)

A 1928 attempt to found a Waldorf school in Nuremberg met with resistance from the Bavarian Education Ministry, which stated that there was the "no need in Bavaria for independent schools employing novel ideas, especially when they had no religious ties."

Second World War

The Stuttgart school grew rapidly, opening parallel classes, and by 1938 schools inspired by the original school or its pedagogical principles had been founded in the United States, UK, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Norway, Austria, Hungary, and in other towns in Germany. Political interference from the Nazi regime limited and ultimately closed most Waldorf schools in Europe; the affected schools, including the original school, were reopened after the Second World War.[5]

Present-day

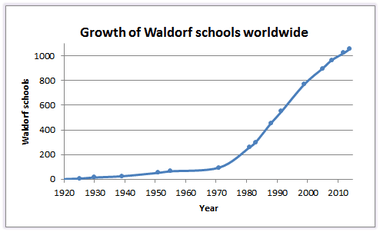

Three-quarters of the Waldorf schools today are located in Europe; schools are now being established in Eastern Europe, where communist regimes forbade Waldorf schools until their overthrow in 1989. In the English-speaking world, there are about 200 schools in the United States, 70 in Australia and New Zealand, 40 in Great Britain, and 30 in Canada; there are also many schools in New Zealand and South Africa.[1]

World-wide system of schools

Germany, the United States and the Netherlands have the largest number of schools, while Norway, Switzerland and the Netherlands have the greatest concentration of schools per population.

Australia

All independent schools in Australia receive partial government funding,[7] including the currently approximately 40 independent Steiner-Waldorf schools. In addition, 10 schools administered by the state are currently operating Steiner programs.[8] In 2006, state-run Steiner schools in Victoria, Australia were challenged by parents and religious experts over concerns that the schools derive from a spiritual system (anthroposophy); parents and administrators, as well as Victorian Department of Education authorities, presented divergent views as to whether spiritual or religious dimensions influence pedagogical practice. If present, these would contravene the secular basis of the public education system.[9]

A detailed. History of the Australian Waldorf schools has been written.[10]

Canada

There are more than 30 independent Waldorf schools in Canada; for a current list see here.

State schools using Waldorf-based methods include:

- French speaking: Chambly, Montreal, Waterville, Victoriaville, and Ottawa

- English speaking: Edmonton, Calgary and Kelowna.

Finland

In Finland there are 24 Steiner schools operating with 95 - 100% state financing.[11]

Germany

In the mid-1930s, the Nazi government began to pressure independent schools in Germany to conform to National Socialist social and educational principles or else face closure. By 1937, most of the German Waldorf schools had decided to cease operation rather than compromise their approach. In 1941, the last Waldorf school operating in Germany (in Dresden) was closed by the Gestapo, as was the school in The Hague, in the occupied Netherlands.[12]

After the Second World War, many of the earlier schools were re-established, and new schools founded at a rapid pace. A second boom in school foundation took place beginning in the 1970s.

There are now close to 200 schools in Germany.

United Kingdom

Various headmasters, teachers, and schools in Great Britain showed an early interest in the new educational methods; as a result Rudolf Steiner held a series of three lectures - in August, 1922 (Oxford), 1923 (Ilkley) and 1924 (Torquay) - introducing Waldorf principles. A number of groups then formed either seeking to transform their existing schools along Waldorf lines (e.g. The New School, Kings Langley in Hertfordshire) or to found new institutions.

- In 1922, a small boarding school housed at Friars Wood and located in the grounds of the former Royal Palace of the Plantagenet Kings of England at Kings Langley, in Hertfordshire, became the first school in the United Kingdom to seek to transform itself along Waldorf lines. However, while the transformation process began in 1922, it took a decade and a half to complete. During that time the school added extensive new buildings, opening fully in 1949 when it became known as 'The New School' Kings Langley (in an attempt not to be confused with nearby Kings Langley Grammar School - now Kings Langley Secondary School). Today, nearly sixty years on, 'The New School' has changed its name, and is simply known as Rudolf Steiner School Kings Langley.

- In 1925, a school was founded near London but relocated during World War II to Minehead and again after the war to Forest Row, Sussex, in the process changing its name to Michael Hall. The school is therefore recognized as the first Waldorf school in Britain.

- In 1934 a small Steiner school was founded in Ilkeston, Michael House school

- Wynstones School in Gloucester was founded by a small group of English teachers in 1935. Several prominent German Waldorf school teachers fleeing the Nazi regime supported the school's development in its early years, including Walter Johannes Stein, Ernst Lehrs, Eugen Kolisko and Bettina Mellinger.

- Edinburgh Steiner School in Edinburgh, Scotland was also founded around 1935.

These four, which grew to become comprehensive schools for ages 12 through 18, became the mainstay of the Waldorf movement in Britain for many years, and they remain the only British schools to provide education up until age 18.

In 1938, a small group of refugees from the Nazis, led by Karl Konig, founded the first school (in Britain) providing special education on Waldorf principles. These Steiner special schools, part of the Camphill movement of communities for the handicapped, spread widely throughout Britain and, later, in many other countries in the world.

Beginning in the late 1940s, further schools were founded, including

- Elmfield school in Stourbridge

A increase in new schools occurred in the 1970s, and another in the 1990s, continuing today. After repeated initiatives to open a school in London; there are now four such schools:

- St. Paul's school, in Islington

- St. Michael Steiner school

- Greenwich Steiner school, in Greenwich

- Waldorf School of South West London, in Streatham

In July 2008, the Hereford Waldorf School in Much Dewchurch, Herefordshire, U.K. secured funding to become a state-funded academy specializing in the natural environment, to be known as The Steiner Academy Hereford.[13]

There are now about 40 Waldorf/Steiner schools in Great Britain and Ireland, which together make up the Steiner Waldorf Schools Fellowship.

United States

Milestones in the early years of Waldorf education include:

- 1928 - Rudolf Steiner School of New York City becomes the first Waldorf School in the US.

- 1941 - Kimberton Waldorf School is founded in Pennsylvania.

- 1947 - The Waldorf School of Garden City is created as part of Adelphi University.

- 1942 - High Mowing Waldorf School, a boarding high school in Wilton, New Hampshire opens.

Three more Waldorf schools were founded in the 1950s, and five in the 1960s. In 1968 the original Association of Waldorf Schools was founded with these twelve schools. With the 1970s came expansive growth leading to the more than 250 schools and early childhood programs today . Thirty-seven new high schools have been started in the last decade. The growth of Waldorf schools in the U.S. has followed a smooth curve, roughly doubling every ten years.[14]

In the 1990s, the first public Waldorf school was established when a principal of an inner-city public school in Milwaukee became interested in using Waldorf methods. The school is now known as the Urban Waldorf Elementary School of Milwaukee. The next public school to incorporate Waldorf methodology was the John Morse Waldorf Method Magnet School in Sacramento, California. A number of public school systems in other cities, including Los Angeles, have also established public Waldorf schools.

Waldorf charter schools have been established in California and Arizona.

In the 1990s, a Waldorf school was established in the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota as a bridge between the traditional spirituality of Native Americans and modern American society.

The U.S., Canadian and Mexican schools are represented by the Association of Waldorf Schools of North America. Waldorf and Steiner are registered and protected names, and in the United States, the Association of Waldorf Schools of North America (AWSNA) protects this usage. Schools that use substantial portions of the methodology of Waldorf education but are not independent enough to apply all of the latter's principles refer to themselves as Waldorf-method, or "Waldorf Inspired" schools; these are primarily found as charter schools which are part of the public school system in the United States and, as government schools, are not included in the above figures.

As of 2011 there are 44 publicly funded Waldorf schools in the United States; some of these are state-run public schools, while 18[15] are charter schools.

- The first US public Waldorf school, the Milwaukee Urban Waldorf School, began using Waldorf methods in 1991; since switching to Waldorf methods, the school showed an increase in parental involvement, a reduction in suspensions, improvements in standardized test scores for both reading and writing (counter to the district trend), while expenditures per pupil were below many regular district programs.[16]

- The country's first public Waldorf high school, the George Washington Carver School of Arts and Sciences, was founded in Sacramento, CA in 2008. Over the school's first three years, test scores rose dramatically; from 67% of 11th graders scoring below or far below basic standards to 12% doing so. The school's teachers also prefer the new approach.[17]

- Waldorf students tend to score considerably below district peers in the early years of elementary education and equal to, or in some cases considerably above, district peers by eighth grade. Some charter and public schools have responded to this data by increasing the schools' focus on academic learning in the early grades.[17]

- California has more publicly funded Waldorf schools than any other US state.

Internal organization

Waldorf schools are "self-administered." Based on a model of collaborative leadership, the College or Council of Teachers is the primary governing body working to direct the school. In the United States, these governing bodies in conjunction with Boards of Trustees work to keep schools independent from government directives on curriculum, testing, hiring and standards in Waldorf schools. Globally, the majority of Waldorf schools are independent, so each school may have different structures and policies. However, Waldorf schools generally give their teachers the right to make decisions about the school's pedagogy.

A number of schools in New Zealand and Australia have close links with, or are overseen by State education authorities. Some Australian schools offer a "dual curriculum" with students attending either the "Steiner stream" or "mainstream" (examples include East Bentleigh Primary School, and Collingwood College).

Notes & references

- 1 2 Statistics for Waldorf schools worldwide

- ↑ Johannes Hemleben, Rudolf Steiner: A documentary biography, Henry Goulden Ltd, ISBN 0-904822-02-8, pp. 121-126 (German edition Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag ISBN 3-499-50079-5).

- ↑ Paull, John (2010) "A Postcard from Oxford: Rudolf Steiner at Manchester College", "Journal of Bio-Dynamics Tasmania", 100: 6-14.

- ↑ Paull, John (2011) Rudolf Steiner and the Oxford Conference: The Birth of Waldorf Education in Britain. European Journal of Educational Studies, 3(1): 53-66.

- ↑ P. Bruce Uhrmacher, "Uncommon Schooling: A Historical Look at Rudolf Steiner, Anthroposophy and Waldorf Education", Curriculum Inquiry, Vol. 25, No. 4. Winter 1995. Abstract

- ↑ Data drawn from Helmut Zander, Anthroposophie in Deutschland, 2 volumes, Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht Verlag, Göttingen 2007, ISBN 9783525554524; Dirk Randall, "Empirische Forschung und Waldorfpädogogik", in H. Paschen (ed.) Erziehungswissenschaftliche Zugänge zur Waldorfpädagogik, 2010 Berlin: Springer 978-3-531-17397-9; "Introduction", Deeper insights in education: the Waldorf approach, Rudolf Steiner Press (December 1983) 978-0880100670. p. vii; L. M. Klasse, Die Waldorfschule und die Grundlagen der Waldorfpädagogik Rudolf Steiners, GRIN Verlag, 2007; Ogletree E J "The Waldorf Schools: An International School System." Headmaster U.S.A., pp8-10 Dec 1979; Heiner Ullrich, Rudolf Steiner, Translated by Janet Duke and Daniel Balestrini, Continuum Library of Educational Thought, v. 11, 2008 ISBN 9780826484192.

- ↑ Independent Schooling in Australia Snapshot 2010, study by Independent Schools Queensland

- ↑ Rout, Milanda (July 28, 2007). "Questions about Steiner's classroom". The Australian. Retrieved December 1, 2011.

- ↑ Steiner education in state schools. ABC National Radio. 25 July 2007 Religion Report, I, 1 August 2007 Religion Report II

- ↑ WALDORF (RUDOLF STEINER) SCHOOLS AS SCHOOLS IN THE PROGRESSIVE EDUCATION TRADITION, Alduino Bartolo Mazzone

- ↑ Finnish Steiner schools

- ↑ Uwe Werner and Christoph Lindenberg, Anthroposophen in der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus (1933-1945), Oldenbourg Verlag, 1999, ISBN 3-486-56362-9.

- ↑ Bowen, Mark (24 July 2008). "New academy to open in Hereford". Hereford Times. Retrieved 2008-07-25.

- ↑ Stephen K. Sagarin, Promise and compromise: A history of Waldorf schools in the United States, 1928--1998, Ph. D. thesis, Columbia University, 2004.

- ↑ list of charter schools in the USA

- ↑ Dr. Richard R. Doornek, Educational Curriculum specialist with the Milwaukee Public Schools quoted in Phaizon Rhys Wood, Beyond Survival: A Case Study of the Milwaukee Urban Waldorf School, dissertation, School of Education, University of San Francisco, 1996

- 1 2 Pappano, Laura (November–December 2011). Harvard Education Letter. 27 (6). Missing or empty

|title=(help)

Bibliography

- Hardorp, Detlef, "Zur Entwicklung und Ausbreitung der Waldorfpädagogik", in Basiswissen Pädagogik. Reformpädagogische Schulkonzepte", Band 6: "Waldorf-Pädagogik". Schneider Verlag (Hohengehren) 2002, pp. 12–52.