History of the Tlingit

The history of the Tlingit involves both pre-contact and post-contact historical events and stories. The traditional history involved creation stories, the Raven Cycle and other tangentially related events during the mythic age when spirits freely transformed from animal to human and back, and the migration story of coming to Tlingit lands, clan histories More recent tales describe events near the time of first contact with Europeans. At that point, European and American historical records come into play, and though modern Tlingits have access to and review these historical records, they continue to maintain their own historical record by telling stories of ancestors and events important to them against the background of the changing world.

Creation story and the Raven Cycle

Stories about Raven are unique in Tlingit culture in that though they technically belong to clans of the Raven moiety, most are openly and freely shared by any Tlingit no matter their clan affiliation. They also make up the bulk of the stories that children are regaled with when young. Raven Cycle stories are often shared anecdotally, the telling of one inspiring the telling of another. Many are humorous, but some are serious and impart a sense of Tlingit morality and ethics, and others belong to specific clans and may only be shared under appropriate license. Some of the most popular are known to other tribes along the Northwest Coast, and provide creation myths for the everyday world.

The Raven Cycle stories contain two different Raven characters, though most storytellers don't clearly differentiate them. One is the creator Raven who brings the world into being and is sometimes the same as the Owner of Daylight. The other is the childish Raven, who is always selfish, sly, conniving, and hungry. Comparing a few of the stories reveals logical inconsistencies between the two. This is usually explained as involving a different world where things did not make logical sense, a mythic time when the rules of the modern world did not apply.

The theft of daylight

The most well recognized story of is that of the Theft of Daylight, in which Raven steals the stars, the moon, and the sun from Naas-sháki Yéil or Naas-sháki Shaan, the Raven (or Old Man) at the Head of the Nass River. The Old Man is very rich and owns three legendary boxes that contain the stars, the moon, and the sun; Raven wants these for himself (various reasons are given, such as wanting to admire himself in the light, wanting light to find food easily, etc.). Raven transforms himself into a hemlock needle and drops into the water cup of the Old Man's daughter while she is out picking berries. She becomes pregnant with him and gives birth to him as a baby boy. The Old Man dotes over his grandson, as is the wont of most Tlingit grandparents. Raven cries incessantly until the Old Man gives him the Box of Stars to pacify him. Raven plays with it for a while, then opens the lid and lets the stars escape through the chimney into the sky. Later Raven begins to cry for the Box of the Moon, and after much fuss the Old Man gives it to him but not before stopping up the chimney. Raven plays with it for a while and then rolls it out the door, where it escapes into the sky. Finally Raven begins crying for the Box of the Sun, and after much fuss finally the Old Man breaks down and gives it to him. Raven knows well that he cannot roll it out the door or toss it up the chimney because he is carefully watched. So he finally waits until everyone is asleep and then changes into his bird form, grasps the sun in his beak and flies up and out the chimney. He takes it to show others who do not believe that he has the sun, so he opens the box to show them and then it flies up into the sky where it has been ever since.

The Tlingit migration

There are a few variations of the Tlingit story of how they came to inhabit their lands. All are fairly similar, and one will be detailed here. They vary mostly in location of the events, with some being very specific about particular rivers and glaciers, others being more vague. The particular one presented here involves some interesting relationship explanations between the Tlingit and their inland neighbors, the Athabaskans. Note that the particular Athabaskan group is not noted, and it seems to be indeterminate. It may in fact refer to a time before the Athabaskans had developed into the multiplicity of peoples that they are today.

All stories are considered property in the Tlingit cultural system, such that sharing a story without the proper permission of its owners is a breach of Tlingit law. However, the stories of the Tlingit people as a whole, the creation myths, and other seemingly universal records are usually considered to be property of the entire tribe, and thus may be shared without particular restriction. It is however important to the Tlingit that the details be correct, for if not this can lead to perpetuations of error and worsen the transmission of the information in the future, as well as degrade the value of the knowledge.

The story begins with the Athabaskan (Ghunanaa) people of interior Alaska and western Canada, a land of lakes and rivers, of birch and spruce forests, and the moose and caribou. Life in this continental climate is harsh, with bitterly cold winters and hot summers. One year the people had a particularly poor harvest over a summer, and it was obvious that the winter would bring with it many deaths from starvation. The elders gathered together and decided that people would be sent out to find a land rumored to be rich in food, a place where one did not even have to hunt for something to eat. A group of people were selected and sent out to find this new place, and would come back to tell the elders where this land could be found. They were never heard from again. However, we now know that these people were the Navajo and Apache, for they left the Athabaskan lands for a different place far south of their home, and yet retain a close relationship with their Athabaskan ancestors.

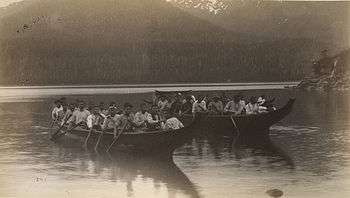

Over the winter countless people died. Again, the next summer's harvest was poor, and the life of the people was threatened. So once again, the elders decided to send out people to find this land of abundance. These people traveled a long distance, and climbed up mountain passes to encounter a great glacier. The glacier seemed impassable, and the mountains around it far too steep for the people to cross. They could however see how the meltwater of the glacier traveled down into deep crevasses and disappeared underneath the icy bulk. The people decided that some strong young men should be sent down to follow this river to see if it came out on the other side of the mountains. But before these men had left, an elderly couple volunteered to make the trip. They reasoned that since they were already near the end of their lives, the loss of their support to the group would be minimal, but the loss of the strong young men would be devastating. The people agreed that these elders should travel under the glacier. They made a simple dugout canoe and took it down the river under the glacier, and came out to see a rocky plain with deep forests and rich beaches all around. The people followed them down under the glacier and came into Lingít Aaní, the rich and bountiful land that became the home of the Tlingit people. These people became the first Tlingits.

Another theory of Tlingit migration is that of the Beringia Land Bridge. Coastal people in general are extremely aggressive; whereas interior Athapascan people are passive. Tlingit culture, being the fiercest among the coastal nations due to their northernmost occupation, began to dominate the interior culture as they traveled inland to secure trading alliances. Tlingit traders were the "middlemen" bringing Russian goods inland over the Chilkoot Trail to the Yukon, and on into Northern British Columbia. As the Tlingit people began marrying interior people, their culture became the established "norm." Soon the Tlingit clan and political structure, as well as customs and beliefs dominated all other interior culture. To this day, Tlingit regalia, language, clan structure, political structure, and ceremonies including beliefs are evident in all interior culture. The Athapascan way of life is now embedded with the Tlingit people's lifestyle.

Clan histories

The clans were Yeil, or Raven; Gooch, or Beaver; and Chaak, or Eagle.

Each clan in Tlingit society has its own foundation history. These stories are private property of the clan in question and thus may not be shared here. However, each story describes the Tlingit world from a different perspective, and taken together the clan histories recount much of the history of the Tlingits before the coming of the Dléit Khaa, the white people.

Typically, a clan history involves an extraordinary event that brought some family or group of families together, separating them from other Tlingits. Some clans seem to be older than others, and often this is notable by their clan histories having mostly mythic proportions. Younger clans seem to have histories that tell of breaking apart from other groups due to internal conflict and strife or the desire to find new territory. For example, the Deisheetaan descend from the Ghaanaxh.ádi, but their clan foundation story tells little or nothing of this relationship. In contrast, the Khák'w.wedí who are descended from the Deisheetaan usually mention their connection as an aside in the telling of their foundation story. Presumably this is the case because their separation was more recent, and is thus well remembered, whereas the separation of the Deisheetaan from the Ghaanaxh.ádi is less apparent in the minds of the Deisheetaan clan members.

First contact

A number of both well-known and undistinguished European explorers investigated Lingít Aaní and encountered the Tlingit in the earliest days of contact. Most of these exchanges were congenial, despite European fears to the contrary. The Tlingit rather quickly appreciated the trading potential for valuable European goods and resources, and exploited this whenever possible in their early contacts. On the whole the European explorers were impressed with Tlingit wealth, but put off by what they felt was an excessive lack of hygiene. Considering that most of the explorers visited during the busy summer months when Tlingit lived in temporary camps, this impression is unsurprising. In contrast, the few explorers who were forced to spend time with the Tlingit Tribe during the inclement winters made mention of the cleanliness of Tlingit winter homes and villages.

- Bering and Chirikov (1741)

Vitus Bering was separated from Aleksei Chirikov and only reached as far east as Kayak Island. However Chirikov traveled to the western shores of the Alexander Archipelago. He lost two boats of men around Lisianski Strait at the northern end of Chichagof Island. Subsequently Chirikov encountered Tlingit whom he felt were hostile, and returned west.

- First Bucareli Expedition (1774)

Juan Josef Pérez Hernández sent by Don Antonio María de Bucareli y Ursúa, Viceroy of New Spain, to explore to north 60 latitude in 1774. Accompanied by Fray Juan Crespí and Fr. Tomás de la Peña Suria (or Savaria). Suria executed a number of drawings that today serve as invaluable records of Tlingit life in the precolonial period.

- Second Bucareli Expedition (1775)

Lt. Bruno de Hezeta (or Heceta) commanded the expedition aboard the Santiago, with Lt. Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra leading the Sonora as second in command. Hezeta returned to Mexico shortly after a massacre by the Quinault near the Quinault River in modern Washington, but Bodega y Quadra insisted upon completing the mission to reach 60° north latitude. He traveled almost as far as Sitka, Alaska to 59° north, claimed possession of the lands he encountered for Spain, and named Mt. Edgecumbe as "Mount Jacinto". It is unclear whether the expedition ever encountered the Tlingit.

- James Cook (1778)

James Cook acquired possession of the journals of Bodega y Quadra's second commander Francisco Antonio Mourelle and of maps created from the two previous Bucareli Expeditions. This inspired him to investigate the northwest coast of America on his third voyage, in search of the Northwest Passage.

- Third Bucareli Expedition (1779)

Lt. Ignacia de Arteaga officially led this expedition in the Princesa, however Bodega y Quadra was the more experienced explorer and accompanied the expedition aboard the Favorita. They made contact and traded with the Tlingits around Bucareli Bay (Puerto de Bucareli). They also named Mount Saint Elias.

- Potap Zaikov

- La Pérouse (1786)

Jean-François de Galaup, comte de La Pérouse

- George Dixon (1787)

- James Colnett (1788)

- Ismailov and Bocharov (1788)

Gerasim Izmailov and Dmitry Bocharov

- William Douglas (1788)

- Alessandro Malaspina (1791)

Alessandro Malaspina, after whom the Malaspina Glacier is named, explored the Alaskan coast as far north as Prince William Sound. His expedition made contact with the Laxhaayík Khwáan of the Yakutat area upon reaching Yakutat Bay.

- George Vancouver (1794)

Fur trade

In 1852 Chilkat Tlingit warriors attacked and burned Fort Selkirk, Yukon, the Hudson's Bay Company post at the juncture of the Yukon and Pelly Rivers. The Chilkat had been acting as middlemen between the Company and the Athapaskan people of the interior (along pre-existing trade routes), and were unwilling to be cut out of the arrangement.

In 1855 an alliance of Tongass Tlingit (Stikines) and Haida raided Puget Sound on a slaving expedition. They were confronted at Port Gamble, Washington Territory by the USS Massachusetts and other naval vessels and suffered casualties, including a prominent Haida chief. A return expedition by the alliance the following year was punitive in character, with Isaac N. Ebey chosen at random as a high-ranking white man whose death would avenge the death of one of the raiding chiefs the year before. The territorial government pressed the colonial government of Vancouver Island to apprehend the killer, but the British had insufficient military capacity to take on the allied Haida and Tlingit and the killer was never identified or caught.

American military rule

In March 1867, the United States purchased Alaska from the Russian Empire. Formal transfer of Russia's claimed colony to the United States took place in October in Sitka. The territory was designated the "Department of Alaska" and assigned to the U.S. Army for occupation and rule. American military rule under the U.S. Army and then U.S. Navy lasted until 1884, and was characterized by inconsistency, violence, and legal ambiguity. Historian Bobby Lain described Alaska at this time as "an insular colony, acquired before the United States was ready for overseas colonies."[1]

The Tlingit were heavily impacted by American military rule, particularly in violent attacks at Sitka, Kake, and Wrangell in 1869, and at Angoon in 1882. By the 1880s, the American administration had recruited some Tlingit to serve as policemen in the indigenous population, particularly in Sitka. Some prominent Tlingit such as Anaxóots became policemen, but their newly claimed legal authority in the community sometimes clashed with existing Tlingit norms of conflict resolution between clans.

The bombardment of Angoon

At a rendering plant located near Angoon in October 1882, a shaman and aristocrat named Til'tlein was killed in an accident that involved the factory's boats and harpoon bombs. Another man had been violently killed recently, and his relatives had not been compensated by the factory managers for his death, a customary Tlingit practice that they had honored previously. The Tlingits had let the previous matter rest, to maintain friendly relations. However, when Til'tlein was killed and the owners again refused to compensate his survivors, the Angoon residents followed traditional Tlingit practice: they seized the boats and weapons involved in the death and took a few whites hostage until the factory managers repaid them for the deaths. They claimed compensation of two hundred blankets from the factory.

Incensed at the theft and perhaps misunderstanding the situation as a threat, the owners sent word to the US Naval Commander Merriman in Sitka. Merriman came to Angoon aboard the revenue cutter USS Corwin and demanded that the Angoon people return the boats and men and pay a fine of four hundred blankets in twenty-four hours or suffer bombing from the cutter's cannons. The following morning only 80 blankets were produced and Merriman proceeded to destroy the canoes on the beach, shell the houses and storehouses, and send a landing party in to loot and burn the remaining town.

The looting and burning of the storehouses destroyed most of the Angoon people's possessions and food they had put up for winter, and that year many people died of starvation. It took five years for the town to rebuild to the size it was before the bombing. This incident, concomitant with the gold rush in Juneau, forced the US government to recognize the need for a formal Territorial Government to replace the martial law that had been in place since the Alaska Purchase.

The residents of Angoon have long held out for a formal apology for what they consider was undue terrorizing punishment for a cultural misunderstanding. In 1973 the US government offered a ninety thousand dollar settlement to the village of Angoon in response to the bombardment, but the government and the US Navy declined to offer a formal apology. In 1982, on the centennial of the bombing, Angoon held a memorial potlatch. Tlingit dignitaries from all across Southeast Alaska and Governor Jay Hammond attended. The people of Angoon formally made public their feelings and opinions on the matter, and demanded an apology from the US Navy. No representatives of the Navy attended, despite a formal invitation, and neither the Government or the Navy made an apology, despite repeated requests from the town government, the Tlingit tribal organizations, and representatives of the State of Alaska.

Early fishing industry

The first American industrial fish canneries were established in Tlingit territory in 1878 at Klawock (Lawáak) and Sitka. Some Tlingit readily sold fish to the canneries or worked for wages processing fish. In the summer of the same year, Tlingit led by Anaxóots of the Kaagwaantaan protested the arrival of eighteen Chinese workers in Sitka, demanding that the Chinese would not take their jobs. The American managers reportedly resolved the conflict with promises that the Chinese would only work at skills in the cannery that Tlingit had not been taught, and if Tlingit learned those skills they would replace the Chinese.[2]

Alaska Native Brotherhood and recognizing rights

Two Tlingit brothers initially created the Alaska Native Brotherhood in 1912 in Sitka in order to pursue the privileges of whites in the area at the time. The Alaska Native Sisterhood followed. ANB and ANS now function as nonprofit organizations serving to assist in societal development and the preservation of Native culture, and ensure all people are treated equally.

Elizabeth Peratrovich was a renowned member of the ANS for whom in 1988 the State of Alaska designated a state holiday, February 16.

World War II

Aleuts were forcibly encamped by the United States government throughout Southeast Alaska during World War II.

Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act

Tlingits were an important driving force behind passage of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of December 18, 1971.

Today

Today, some of the inland Tlingit people live in communities in Atlin, British Columbia, as well as in the Yukon communities of Whitehorse, Carcross and Teslin. There are also the coastal Tlingit people who reside in Alaska. Every two years the inland and coastal Tlingits have a celebration of their culture; Juneau, Alaska has their celebration on the even-numbered years and Teslin Yukon Territory has theirs on the odd-numbered years. Events include traditional performances, cultural demonstrations, nightly feasts that are held by the three inland Tlingit communities, hand game tournaments, canoeing events, a kid zone, an artist market and food vendors.

References

- ↑ Bobby Dave Lain, “North of Fifty-Three Army, Treasury Department, and Navy Administration of Alaska, 1867-1884," (University of Texas, Austin, 1974), p. iii.

- ↑ Robert E. Price, The Great Father in Alaska: The Case of the Tlingit and Haida Salmon Fishery (Douglas, Alaska: First Street Press, 1990), p. 49-51.