Hoochie Coochie Man

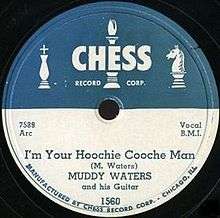

| "I'm Your Hoochie Cooche Man" | |

|---|---|

| |

| Single by Muddy Waters | |

| B-side | "She's So Pretty" |

| Released | 1954 |

| Format | 10-inch 78 rpm & 7-inch 45 rpm records |

| Recorded | Chicago, January 7, 1954 |

| Genre | Chicago blues |

| Length | 2:47 |

| Label | Chess (no. 1560) |

| Writer(s) | Willie Dixon[lower-alpha 1] |

| Producer(s) | Leonard Chess |

| ISWC | T-070.240.830-7 |

"Hoochie Coochie Man" (originally titled "I'm Your Hoochie Cooche Man")[lower-alpha 2] is a blues standard written by Willie Dixon and first recorded by Muddy Waters in 1954. The song references hoodoo folk magic elements and makes novel use of a stop-time musical arrangement. It became one of Waters' most popular and identifiable songs and helped secure Dixon's role as Chess Records' chief songwriter.

The song is a classic of Chicago blues and one of Waters' first recordings with a full backing band. Dixon's lyrics build on Waters' earlier use of braggadocio and themes of fortune and sex appeal. The stop-time riff was "soon absorbed into the lingua franca of blues, R&B, jazz, and rock and roll", according to musicologist Robert Palmer, and is used in several popular songs.[3] When Bo Diddley adapted it for "I'm a Man", it became one of the most recognizable musical phrases in blues.

After the song's initial success in 1954, Waters recorded several live and new studio versions. The original appears on the 1958 The Best of Muddy Waters album and many compilations. Numerous musicians have recorded "Hoochie Coochie Man" in a variety of styles, making it one of the most interpreted Waters and Dixon songs. The Blues Foundation and the Grammy Hall of Fame recognize the song for its influence in popular music and the US Library of Congress' National Recording Registry selected it for preservation in 2004.

Background

Between 1947 and 1954, Muddy Waters charted a number of hits recording for Chess Records and its Artistocrat predecessor.[4] One of his first singles was "Gypsy Woman", recorded in 1947.[5] The song shows Delta blues guitar-style roots, but the lyrics place "emphasis on supernatural elements—gypsies, fortune telling, [and] luck", according to musicologist Robert Palmer.[6]

You know the gypsy woman told me that you your mother's bad luck child

Well you havin' a good time now, but that'll be trouble after awhile[1]

- ^ Palmer 1981, p. 158.

Waters expanded the theme in "Louisiana Blues", which was recorded in 1950 with Little Walter accompanying on harmonica.[7] He sings of traveling to New Orleans, Louisiana, to acquire a mojo hand, a hoodoo amulet or talisman;[8] with its magical powers, he hopes "to show all you good lookin' women just how to treat your man".[9] Similar lyrics appeared in "Hoodoo Hoodoo", a 1946 recording by John Lee "Sonny Boy" Williamson: "Well now I'm goin' down to Louisiana, and buy me another mojo hand".[10][lower-alpha 3] Although Waters was ambivalent about hoodoo,[lower-alpha 4] he saw the music as having its own power:[9]

When you're writin' them songs that are coming from down that way [Mississippi Delta], you can't leave out somethin' about that mojo thing. Because this is what black people really believed in at that time ... even today [circa 1980], when you play the old blues like me, you can't get from around that.[12]

From 1946 to 1951, Willie Dixon sang and played bass with the Big Three Trio.[13] After the group disbanded, he worked for Chess Records as a recording session arranger and bassist.[14] Dixon wrote several songs, but label co-owner Leonard Chess failed to show any interest at first.[15] Finally, in 1953, Chess used two of Dixon's songs: "Too Late", recorded by Little Walter,[16] and "Third Degree", recorded by Eddie Boyd.[17] "Third Degree" became Dixon's first composition to enter the record charts.[18] In September, Waters recorded his "Mad Love (I Want You to Love Me)",[2] which Dixon biographer Mitsutoshi Inaba calls "a test piece for the forthcoming 'Hoochie Coochie Man'" because of its shared lyrical and musical elements.[19] The song became Waters' first record chart success in nearly two years.[4]

The term "hoochie coochie", with variations in the spelling, is used in different contexts. Appearing in the late 19th century, the hoochie coochie was a sexually provocative dance. Don Wilmeth identifies it as "a precursor of the striptease ... from the belly dance but punctuated with bumps and grinds and a combination of exposure, erotic movements, and teasing."[20] By one account, it first appeared at the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition in 1876[21] and was a popular attraction at the 1893 Chicago World's Fair.[22] The dance is associated with entertainers Little Egypt[23] and Sophie Tucker,[24] but by the 1910s it declined in popularity.[lower-alpha 5] "Hoochie coochie" is also used to refer to a sexually attractive person or a practitioner of hoodoo.[19] In his autobiography, I Am the Blues, Dixon included "hoochie coochie man" in his examples of a seer or a clairvoyant with a connection to folklore of the American South: "This guy is a hoodoo man, this lady is a witch, this other guy's a hoochie coochie man, she's some kind of voodoo person".[26]

Composition and recording

Not long after the success of "Mad Love" in November 1953, Dixon approached Leonard Chess with "Hoochie Coochie Man", a new song he felt was right for Waters.[15] Chess responded, "if Muddy likes it, give it to him".[15] At the time, Waters was performing at the Club Zanzibar in Chicago.[27] During an intermission, Dixon showed him the song.[lower-alpha 6] According to Dixon, Waters took to the tune immediately because it had so many familiar elements and he was able to learn enough to perform it that night.[26] Jimmy Rogers, who was Waters' second guitarist, remembered that it took a little longer:

Dixon came to the club and he would hum it to Muddy and write the lyrics out. Muddy would work them around for a while until he got it down where he could understand it and fool around with it. He would be onstage and try it out, do a few licks of it. We were building the arrangement, that's what we were really doing.[29]

On January 7, 1954, Waters entered the recording studio with his band to record the song.[19] Considered the classic Chicago blues band,[30] music critic Bill Janovitz described Waters' group as "a who's who of bluesmen".[31] Waters sings and plays electric guitar along with Rogers, blues harmonica virtuoso Little Walter, and drummer Elgin Evans, all of whom had been performing with Waters since 1951.[1] (Fred Below, who replaced Evans during 1954, is sometimes listed as the drummer.)[2][32] Pianist Otis Spann, who joined in 1953, and Dixon, in his debut on double bass for Waters' recording session, round out the group.[1] Two takes of the song were recorded.[33] Although there are some moments in the alternate take when a player's timing rushes or drags perceptibly, because the band is so tight, the difference with the master is only six seconds (for a nearly three-minute song).[34][lower-alpha 7]

"Hoochie Coochie Man" follows a sixteen-bar blues progression, which is an expansion of the well-known twelve-bar blues pattern.[32] The first four bars are doubled in length so the harmony remains on the tonic for eight bars or one-half of the sixteen bar progression.[35] Dixon explained that expanding twelve-bar blues was in response to amplification, which gave instruments more sustain.[36] The extra bars also increase the contrasting effect of the repeating stop-time musical figure or riff.[37] For the second eight bars, the song reverts to the last eight of the twelve-bar progression, which functions as a refrain or hook.[37][19] The different textures provides the tune with a strong contrast,[32] which helps underscore the lyrics.[38] The song is performed at a moderate blues tempo (72 beats per minute) in the key of A.[39] It is notated in 12

8 time and contains three sixteen-bar sections.[40]

A key feature of the song is the use of stop time, or pauses in the music, during the first half of the progression.[30] This musical device is commonly heard in New Orleans jazz,[30] when the instrumentation briefly stops, allowing for a short instrumental solo before resuming.[41] However, Waters' and Dixon's use of stop time serves to heighten the tension through repetition,[42] followed by a vocal rather than an instrument fill.[43] The accompanying riff, which Dixon described as a five-note figure,[26] is similar to that of "Mad Love".[19] He attributed it to the band[30] and using such a phrase for eight bars was a new approach.[42] Although Palmer comments that the entire group phrases the riff in unison,[30] Boone describes it as a "heavy, unhurried counterpoint by all the instruments together".[35] Campbell identifies the opening as actually having "two competing riffs"[32] or contrapuntal motion, with one played by Little Walter on an amplified harmonica and another by Waters on electric guitar.[32]

For the second eight-bars of the progression, the song follows the standard I–IV–V7 structure, which maintains its connection to traditional blues.[43] The whole band plays it as a shuffle with a triplet rhythm, which Campbell describes as a "free-for-all [with] harmonica trills, guitar riffs, piano chords, thumping bass, [and] shuffle pattern on the drums".[44] He adds that this type of heavy sound was rarely heard in small music combos before rock.[44] However, unlike the polyphony of New Orleans jazz, the instrumentation parallels Waters' aggressive vocal approach and reinforces the lyrics.[35] The players use of amplification, pushed to the point of distortion, is a key feature of Chicago blues and another rock precedent.[44] In particular, Little Walters' overdriven saxophone-like harmonica[45] playing weaves in and out of the vocal lines, which heightens the drama.[46]

Lyrics and interpretation

"Hoochie Coochie Man" is characterized as a "self-mythologizing testament" by Janovitz.[31] The narrator boasts of his good fortune and his effect on women as aided by hoodoo.[19] Waters explored similar themes in earlier songs, but his approach was more subtle.[47] According to Palmer, Dixon upped the ante with more "flamboyance, macho posturing, and extra-generous helping of hoodoo sensationalism".[47] Dixon claimed that the idea of a seer was inspired by history and the Bible.[3] The verses in the song's three sixteen-bar sections proceed chronologically.[48] The opening verse starts before the narrator is born[49] and references Waters' 1947 song "Gypsy Woman":

The gypsy woman told my mother, before I was born

I [sic][a] got a boy child's comin', gonna be a son of a gun

He gonna make pretty womens, jump an' shout

And then the world wanna know, what this all about[2]

- ^ Inaba 2011, p. 87.

- ^ Dixon & Snowden 1989, p. 6.

Cite error: There are<ref group=lower-alpha>tags or{{efn}}templates on this page, but the references will not show without a{{reflist|group=lower-alpha}}template or{{notelist}}template (see the help page).

As a boy in the South, Dixon recalled gypsies in covered wagons plying their trade from town to town.[26] The fortune tellers would emphasize auspicious circumstances to enhance their earnings, especially when doing readings for pregnant women.[50] In the second section, the narrative is in the present and several references are made to charms used by hoodoo conjurers.[51] These include a black cat bone, a John the conqueror root, and a mojo,[52] the last of which figured in "Louisiana Blues". Their magical powers assure that the gypsy's prophecy will be borne out: women and the rest of world will take notice.[53] The song concludes with a final section which projects the good fortune into the future.[53] The number seven is prominent: on the seventh hour, on the seventh day, etc.[54] The stringing together of sevens is another good omen and is analogous to the seventh son of a seventh son of folklore.[55] Dixon later expanded the theme in his 1955 song "The Seventh Son".[56]

Each section is linked by a refrain or recurring chorus.[53] It functions as a hook and it differs from the usual "free-associative aspect" of traditional blues.[41] Writer Benjamin Filene sees this and Dixon's desire to tell complete stories, with the verses building on each other, as sharing elements of pop music.[57] The chorus, "But you know I'm here, everybody knows I'm here, Well you know I'm the hoochie coochie man, everybody knows I'm here",[58] confirms the narrator's identity as both the subject of the gypsy's prophecy as well as an omnipotent seer himself.[53] Dixon felt that the lyrics expressed part of the audience's unfulfilled desire to brag,[29] while Waters later admitted that they were supposed to have a comic effect.[59] Music historian Ted Gioia points to the underlying theme of sexuality and virility as sociologically significant.[60] He sees it as challenge to the fear of miscegenation in the dying days of racial segregation in the United States.[61] Record producer Marshall Chess took a simpler view: "It was sex. If you have ever seen Muddy then, the effect he had on women [was clear]. Because the blues, you know, has always been a women's market".[62]

Releases and charts

In early 1954, Chess Records issued "I'm Your Hoochie Cooche Man" backed with "She's So Pretty" on both the standard ten-inch 78 rpm and the newer seven-inch 45 rpm record single formats. It soon became the biggest hit of Waters' career.[32] The single entered Billboard magazine's Rhythm & Blues Records charts on March 13, 1954, and reached number three on the Juke Box chart and number eight on the Best Seller chart.[4] It remained on the charts for 13 weeks, making it Waters' longest charting record up to that time (two more Waters-Dixon songs, "Just Make Love to Me (I Just Want to Make Love to You") and "Close to You", both later also lasted 13 weeks).[4]

Chess included the song on Waters' first album, the 1958 compilation The Best of Muddy Waters, but retitled it "Hoochie Coochie".[63] Numerous later Waters' official compilations contain it, such as Sail On; McKinley Morganfield a.k.a. Muddy Waters; The Chess Box; His Best: 1947 to 1955; The Best of Muddy Waters – The Millennium Collection; The Anthology (1947–1972); Hoochie Coochie Man: The Complete Chess Masters, Vol. 2: 1952–1958; and The Definitive Collection.[64] Marshall Chess arranged for Waters to remake the song using psychedelic rock-style instrumentation for the 1968 album Electric Mud, which was an attempt to reach a new audience.[65] In 1972, Waters recorded an "unplugged" rendition of the song, with Louis Myers on acoustic guitar and George "Mojo" Buford on unamplified harmonica.[66] Chess released it in 1994 on the Waters rarieties collection One More Mile.[66] He revisited the song with original guitarist Jimmy Rogers in 1977.[67] They re-recorded it for I'm Ready, the Grammy Award-winning album produced by Johnny Winter.[67]

Waters featured the song in his performances and several live recordings have been issued.[64] His acclaimed At Newport 1960, one of the first live blues albums, includes a rendition by his later band with Spann, Pat Hare, James Cotton, and Francis Clay.[68] Other live albums have versions that span his career with different backup bands. These include Live in 1958 (recorded in England in 1958 with Spann and Chris Barber's trad jazz band, released in 1993 and re-released as Collaboration in 1995); Authorized Bootleg: Live at the Fillmore Auditorium – San Francisco Nov 04–06 1966 (released 2009); The Lost Tapes (recorded 1971, released 1999); Muddy "Mississippi" Waters – Live (recorded 1977, released 1979); and Live at the Checkerboard Lounge, Chicago 1981 with members of the Rolling Stones (released 2012).[64]

Influence and recognition

"This classic blues phrase would eventually work its way into the psyche of modern culture by being featured in musical genres from folk to rock and even children's songs as well as being used in television and radio commercials."

—Bryan Grove, Encyclopedia of the Blues (2005)[43]

"Hoochie Coochie Man" represents Waters' recording transition from an electrified, but more traditional Delta-based blues of the late 1940s–early 1950s to a newer Chicago blues ensemble sound.[69] The song was important to Dixon's career and signaled a change as well – Chess became convinced of Dixon's value as a songwriter and secured his relationship as such with the label.[70] Waters soon followed up with several variations on the sixteen-bar stop-time arrangement written by Dixon.[71][31] These include "I Just Want to Make Love to You", "I'm Ready", and "I'm a Natural Born Lover".[72] All of these songs follow a similar lyrical theme and "helped shape Muddy Waters' image as the testosterone king of the blues", according to Gioia.[72]

Bo Diddley modified the song's signature riff for his March 1955 song "I'm a Man".[73] He reworked it as a four-note figure, which is repeated for the entire song without a progression to other chords.[73] Music critic and writer Cub Koda calls it "the most recognizable blues lick in the world".[73] Waters, not to be outdone, responded two months later with an answer song to "I'm a Man", titled "Mannish Boy".[74] "Bo Diddley, he was tracking me down with my beat when he made 'I'm a Man'. That's from 'Hoochie Coochie Man.' Then I got on it with 'Mannish Boy' and just drove him out of my way", Waters recalled.[75] Emphasizing the origin of Bo Diddley's song, Waters sticks to the original first eight-bar phrase from "Hoochie Coochie Man" and includes some of the hoodoo references.[76]

According to Palmer, songwriters adapted the phrase for other artists and it was "soon absorbed into the lingua franca of blues, jazz, and rock and roll".[30] In 1955, songwriters Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller used the riff for "Riot in Cell Block Number 9"[30] (later reworked by the Beach Boys as "Student Demonstration Time") and "Framed" for the R&B group the Robins. "Trouble", another Leiber and Stoller composition that uses the riff, was sung by Elvis Presley in the 1958 musical drama film King Creole. American composer Elmer Bernstein quoted the figure in another film, The Man with the Golden Arm,[30] which received a nomination for an Academy Award for Best Original Score in 1955. Dixon remarked, "we felt like this was a great achievement for one of these blues phrases to be used in a movie".[30]

As numerous artists recorded it in a variety of styles, "Hoochie Coochie Man" became a blues standard.[10][43] Janovitz describes the song as "a vital piece of Chicago-style electric blues that links the Delta to rock & roll".[31] Rock musicians are among the many who have interpreted it.[43] In 1984, Waters' original "I'm Your Hoochie Coochie Man" was inducted into the Blues Foundation Hall of Fame. The Foundation noted that "In addition to countless versions by Chicago blues artists, the song has been recorded by performers as diverse as Jimi Hendrix, Chuck Berry, and jazz organist Jimmy Smith"[77] to which Grove adds B.B. King, Buddy Guy, John P. Hammond, the Allman Brothers Band, and Eric Clapton.[43][lower-alpha 8] A Grammy Hall of Fame Award followed in 1998, which "honor[s] recordings of lasting qualitative or historical significance".[80] The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame's list of the "500 Songs That Shaped Rock and Roll" recognizes the song's influence on rock.[81] Representatives of the music industry and press voted it number 226 for Rolling Stone magazine's list of the "500 Greatest Songs of All Time".[82] In 2004, the National Recording Preservation Board, advisors to the US Library of Congress, selected it for preservation in the National Recording Registry and noted the contributions of the band members.[83]

Notes

Footnotes

- ↑ Although the initial Chess single lists the songwriter as "M. Waters", reissues credit Willie Dixon.[1] BMI shows the Songwriter/Composer as Willie Dixon."I m Your Hoochie Cooche Man (Legal Title) – BMI Work #668840". BMI Repertoire. BMI. Retrieved September 9, 2014.

- ↑ Some of Chess' single pressings also appear as "I'm Your Hoochie Kooche Man";[2] the original 1958 Chess The Best of Muddy Waters lists it as "Hoochie Coochie".

- ↑ In June 1953, seven months before "Hoochie Coochie Man", Junior Wells recorded Williamson's "Hoodoo Hoodoo" as a Chicago blues single with Elmore James titled "Hoodoo Man Blues" and again in 1965 for his Hoodoo Man Blues album.[10]

- ↑ Waters elaborated, "If such a thing as a mojo had've been good, you'd've had to go down to Louisiana to find one. Where we were, in the Delta, they couldn't do no nothin', I don't think. And there is no way I can shake my finger at you and make you bark like a dog, or make frogs and snakes jump out of you. Bullshit. No way".[11]

- ↑ In The Language of the Blues: From Alcorub to Zuzu, Debra Devi offers an alternative definition of a hoochie coochie dancer as a stripper and a hoochie coochie man as a pimp.[25]

- ↑ According to Waters, Dixon followed him into the restroom to pitch him the song.[27] In his autobiography, Dixon wrote that he had Waters get his guitar and they rehearsed the song in the front of the restroom by the door while patrons were coming and going.[28]

- ↑ The recording predated the use of metronomic devices, such as a click track, by recording studios.

- ↑ When English blues singer Long John Baldry took over Cyril Davies' All Stars, he renamed them "Long John Baldry and the Hoochie Coochie Men", as a conscious parallel to the Rolling Stones' use of another Muddy Waters' song.[78] The group lasted about a year and produced one album, Long John's Blues, which also included a version of the song.[79]

Citations

- 1 2 3 Palmer 1989, p. 28.

- 1 2 3 Wight & Rothwell 1991, p. 40.

- 1 2 Palmer 1981, p. 166.

- 1 2 3 4 Whitburn 1988, p. 435.

- ↑ Wight & Rothwell 1991, p. 37.

- ↑ Palmer 1989, pp. 16–17.

- ↑ Palmer 1981, pp. 98–99.

- ↑ Gioia 2008, pp. 218–219.

- 1 2 Palmer 1981, p. 99.

- 1 2 3 Herzhaft 1992, p. 452.

- ↑ Palmer 1981, p. 97.

- ↑ Palmer 1981, pp. 97–98.

- ↑ Dixon & Snowden 1989, pp. 58–59.

- ↑ Dixon & Snowden 1989, p. 81.

- 1 2 3 Dixon & Snowden 1989, p. 83.

- ↑ Snowden 1993, p. 12.

- ↑ Dixon & Snowden 1989, p. 86.

- ↑ Whitburn 1988, p. 52.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Inaba 2011, p. 81.

- ↑ Wilmeth 1981, p. 63.

- ↑ Cohen 1993, p. 126.

- ↑ Stencell 1999, p. 4.

- ↑ Stencell 1999, p. 5–7.

- ↑ Blecha 2004, p. 19.

- ↑ Devi, p. 131.

- 1 2 3 4 Dixon & Snowden 1989, p. 84.

- 1 2 Gordon 2002, p. 123.

- ↑ Dixon & Snowden 1989, p. 123.

- 1 2 Dixon & Snowden 1989, p. 85.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Palmer 1981, p. 167.

- 1 2 3 4 Janovitz, Bill. "Muddy Waters: (I'm Your) Hoochie Coochie Man – Song Review". AllMusic. Rovi Corp. Retrieved August 16, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Campbell 2011, p. 166.

- ↑ Inaba 2011, p. 87.

- ↑ Inaba 2011, pp. 87–88.

- 1 2 3 Boone 2003, p. 72.

- ↑ Inaba, pp. 79–90.

- 1 2 Boone 2003, p. 73.

- ↑ Boone 2003, p. 74.

- ↑ Hal Leonard 1995, p. 112.

- ↑ Hal Leonard 1995, pp. 112–113.

- 1 2 Filene 2000, p. 100.

- 1 2 Inaba 2011, p. 82.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Grove 2005, p. 454.

- 1 2 3 Campbell 2007, p. 80.

- ↑ Gordon 2002, p. 124.

- ↑ Gillett 1972, p. 160.

- 1 2 Palmer 1981, p. 168.

- ↑ Filene 2000, pp. 101–102.

- ↑ Filene 2000, p. 101.

- ↑ Dixon & Snowden 1989, pp. 84–85.

- ↑ Inaba 2011, pp. 85–86.

- ↑ Dixon & Snowden, p. 6.

- 1 2 3 4 Filene 2000, p. 102.

- ↑ Dixon & Snowden 1989, p. 7.

- ↑ Filene 2000, pp. 102–103.

- ↑ Dixon & Snowden 1989, p. 87.

- ↑ Filene 2000, pp. 100–101.

- ↑ Dixon & Snowden 1989, p. 6.

- ↑ Wald 2004, p. 177.

- ↑ Gioia 2008, p. 219–220.

- ↑ Gioia 2008, p. 220.

- ↑ Inaba 2011, p. 80.

- ↑ Palmer 1989, p. 26.

- 1 2 3 "Muddy Waters: Hoochie Coochie Man – Appears On". AllMusic. Rovi Corp. Retrieved September 3, 2014.

- ↑ Gordon 2002, pp. 205–206.

- 1 2 Aldin 1994, p. 21.

- 1 2 Gordon, Rev. Keith A. "Muddy Waters: I'm Ready – Album Review". AllMusic. Rovi Corp. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- ↑ Dahl 1996, p. 269.

- ↑ Filene 2000, p. 99.

- ↑ Eder 1996, p. 72.

- ↑ Inaba 2011, p. 89.

- 1 2 Gioia 2008, p. 222.

- 1 2 3 Koda, Cub. "Bo Diddley: I'm a Man". AllMusic. Rovi Corp. Retrieved September 3, 2013.

- ↑ Herzhaft 1992, p. 454.

- ↑ Gordon 2002, p. 142.

- ↑ Janovitz, Bill. "Muddy Waters: Mannish Boy – Song Review". AllMusic. Rovi Corp. Retrieved September 3, 2014.

- ↑ "Classics of Blues Recording – Singles and Album Tracks". Blues Hall of Fame Inductees Winners. The Blues Foundation. 1984. Retrieved January 10, 2011.

- ↑ Myers 2007, p. 67.

- ↑ Myers 2007, pp. 72–73.

- ↑ "Grammy Hall of Fame Awards – Past Recipients: I". The Recording Academy. 1998. Retrieved January 10, 2011.

- ↑ "500 Songs That Shaped Rock and Roll". Exhibit Highlights. Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. 1995. Archived from the original on 2007. Retrieved January 10, 2011.

- ↑ "The 500 Greatest Songs of All Time". Rolling Stone (963). December 9, 2004. Retrieved January 10, 2011.

- ↑ "The Full National Recording Registry". National Recording Preservation Board. US Library of Congress. Retrieved June 11, 2014.

References

- Aldin, Mary Katherine (1994). One More Mile (CD booklet). Muddy Waters. MCA/Chess. OCLC 30331806. CHD2-9348.

- Blecha, Peter (2004). Taboo Tunes: A History of Banned Bands & Censored Songs. Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN 978-0-87930-792-9.

- Hal Leonard (1995). The Blues. Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN 0-7935-5259-1.

- Boone, Graeme M. (2003). Moore, Allan, ed. The Cambridge Companion to Blues and Gospel Music. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00107-6.

- Campbell, Michael; Brody, James (2007). Rock and Roll: An Introduction (Second ed.). Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-534-64295-2.

- Campbell, Michael (2011). Popular Music in America: And the Beat Goes On (Fourth ed.). Schirmer. ISBN 978-0-8400-2976-8.

- Dahl, Bill (1996). Erlewine, Michael, ed. All Music Guide to the Blues. Miller Freeman Books. ISBN 0-87930-424-3.

- Devi, Debra (2012). The Language of the Blues: From Alcorub to Zuzu. True Nature Books. ISBN 978-1-62407-185-0.

- Dixon, Willie; Snowden, Don (1989). I Am the Blues. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80415-8.

- Eder, Bruce (1996). Erlewine, Michael, ed. All Music Guide to the Blues. Miller Freeman Books. ISBN 0-87930-424-3.

- Filene, Benjamin (2000). Romancing the Folk: Public Memory & American Roots Music. UNC Press Books. ISBN 978-0-8078-4862-3.

- Gillett, Charlie (1972). The Sound of the City. Dell Publishing Co.

- Gioia, Ted (2008). Delta Blues. W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-33750-1.

- Gordon, Robert (2002). Can't Be Satisfied: The Life and Times of Muddy Waters. Little, Brown. ISBN 0-316-32849-9.

- Grove, Bryan (2005). "Hoochie Coochie Man". In Komara, Edward. Encyclopedia of the Blues. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-92699-7.

- Herzhaft, Gerard (1992). "Hoochie Coochie Man". Encyclopedia of the Blues. University of Arkansas Press. ISBN 1-55728-252-8.

- Inaba, Mitsutoshi (2011). Willie Dixon: Preacher of the Blues. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-6993-6.

- Murray, Charles Shaar (1991). Crosstown Traffic. St. Marten's Press. ISBN 0-312-06324-5.

- Myers, Paul (2007). It Ain't Easy: Long John Baldry and the Birth of the British Blues. Greystone Books. ISBN 978-1-55365-200-7.

- Palmer, Robert (1981). Deep Blues. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-006223-8.

- Palmer, Robert (1989). Muddy Waters: Chess Box (Box set booklet). Muddy Waters. Chess/MCA Records. OCLC 154264537. CHD3-80002.

- Snowden, Don (1993). The Essential Little Walter (CD compilation booklet). Little Walter. Chess/MCA. OCLC 29365560. CHD2-9342.

- Stencell, A. W. (1999). Girl Show: Into the Canvas World of Bump and Grind. ECW Press. ISBN 978-1-55022-371-2.

- Wald, Elijah (2004). Escaping the Delta: Robert Johnson and the Invention of the Blues. Amistad. ISBN 0-06-052423-5.

- Whitburn, Joel (1988). Top R&B Singles 1942–1988. Record Research, Inc. ISBN 0-89820-068-7.

- Wight, Phil; Rothwell, Fred (1991). "The Complete Muddy Waters Discography". Blues & Rhythm (200).

- Wilmeth, Don B. (1981). The Language of American Popular Entertainment: A Glossary of Argot, Slang, and Terminology. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-22497-3.