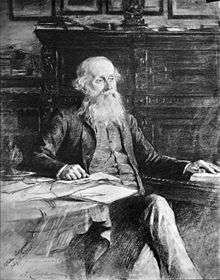

Hugh Cleghorn (forester)

Hugh Francis Clarke Cleghorn of Stravithie, FRSE FLS LLD (9 August 1820 – 16 May 1895) was a Madras-born Scottish physician who worked in India and pioneered as a botanist and in forest conservancy. Cleghorn, sometimes known as the father of scientific forestry in India, was instrumental in the creation of the forest department in the Presidency of Madras. The plant genus Cleghornia was named after him by the botanist Robert Wight. Cleghorn returned to Scotland in 1869 and developed forestry education in Scotland and established a lecturership at the Edinburgh University.

Early life

Cleghorn was born in Madras on 9 August 1820, where his father, Peter (sometime referred to as Patrick) Cleghorn (1 December 1783 – 9 June 1863) was Registrar and Prothonotary (later Administrator-General) in the Supreme Court of the Madras Presidency. His mother Isabella Allan died in Madras (1 June 1824) when he was four years old.[2] His grandfather Professor Hugh Cleghorn (1752–1837) was the first British colonial secretary to Ceylon.[3] The family returned to Stravithie in 1824 and Cleghorn received his early education the High School in Edinburgh. He also experienced rural life and received a training in agriculture. He then went to study at the University of St Andrews. Graduating in 1837, he went on to study medicine at Edinburgh and for five years he apprenticed under the famous surgeon, James Syme. He qualified MD from the University of Edinburgh in 1841. This was also a period in which he developed an interest in botany. He then qualified for the Indian Medical Service and was posted to the Madras Presidency.[4][5]

India

Cleghorn first served in India as an assistant surgeon employed by the East India Company at the Madras General Hospital, then Mysore Commission, until 1848. While at Mysore he took a keen interest in botany, encouraged by Sir William Jackson Hooker[6] who had suggested to him that he "study one plant a day for a quarter of an hour".[7][8] He also received a list of enquiries to pursue from Robert Christison. He had a lot of time between duty at a jail and a hospital and between postings from Dharwad to Trichinopoly. Cleghorn took a special interest in economic botany became involved with forest conservation in Mysore. In 1848, he suffered from "Mysore fever" and returned to Britain and spent time at Torquay but continued his private studies on botany. He was on the verge of resigning from service when he was requested by John Forbes Royle to assist in the cataloguing of exhibits for the Great Exhibition of 1851. Cleghorn returned to India in 1852 on being appointed Professor of Botany and Materia Medica at Madras Medical College by Sir Henry Pottinger. During this period he also became an active member of the Madras Literary Society and the Madras Agri-Horticultural Society.[4][9]

Madras Forest Department

While in Britain in 1848 on sick leave, he gave several speeches about the failure of agriculture in India. These lectures spurred the Government of India to introduce forest conservation policies and Forest Departments in India and other colonies as well. He took part in cataloguing the raw-products shown in 1851. In 1855 Dr. Cleghorn was asked by Lord Harris to organise the Madras Forest Department and started systematic forest conservancy. In 1856 he was appointed Conservator of Forests in Madras Presidency.[4]

Cleghorn saw the growth of the railways as being a major threat to the forests. He had seen a similar pattern in Scotland in the 1850s and he estimated, in the Madras Presidency, that a mile of rail line needed 1760 wooden sleepers which would have a life of eight years. In addition to the sleepers, wood was needed to run the steam engines of the railways apart from their use in steamships. By his estimate, there was no way to maintain the supply without destroying the forests unless some special management was undertaken. He pointed out that Britain was in a better state because of the reserves of coal and the ability to import wood from other parts of its Empire.[4]

Cleghorn, along with Alexander Gibson, Edward Balfour and others believed in the role of forests in hydrology and the flow of rivers. He would comment on the influence of forests on climate in a quest led by the British Association for the Advancement of Science around the 1850s.[4]

Cleghorn's studies in botany were mainly made with a view to applications. In 1853, he published his research on the hedge-plants of the Mysore-Madras region.[10] An earlier "Report on the Hedge Plants of India" read at the meeting of the British Association in 1850 won him a "medium gold medal" of the Highland and Agricultural Society in 1851.[11] In 1856 he wrote a note on the sand-binding plants of the Madras beach.[12][13] In 1853 he published Hortus Madraspatensis, a catalogue of the plants grown in the Agri-Horticultural Society's Garden in Madras.

Cleghorn's persistent campaigning with the Government resulted in the banning of "kumri", a form of shifting cultivation in the Madras Presidency in 1860. The ban was finally ordered while he was again on leave in Britain. Returning to Scotland he married Mabel, daughter of Charles Cowan, Penicuik on 8 August 1861.[5][14]

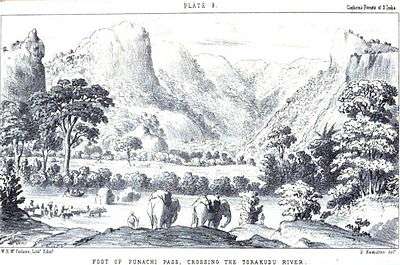

In 1858, Cleghorn visited the Anamalai range along with Major Douglas Hamilton, sent by Sir Patrick Grant as an illustrator, and wrote on the landscape and botany of the region. Other members of the team included Richard Henry Beddome, J.W. Cherry (collector of Coimbatore) and two doctors among others.[15]

In 1861, he returned to take up the post of Joint Commissioner for Conservancy of Forests, a position shared with Dietrich Brandis.

Forests and gardens of South India

In 1861, the book: The forests and gardens of South India, by Hugh Cleghorn and illustrated by Douglas Hamilton, was prepared at the request of Government, principally for the purpose of furnishing a continuous view of forest conservancy in the Madras Presidency during the four years that the department was in operation. One of his goals was to supply a manual to enable the forest assistants in positions of responsibility to act intelligently with good results to the State.[16][17]

Forest Department of India

Cleghorn organised the new Forestry Department in Madras with such astonishing energy and success that in 1861 he was called on to advise Sir Robert Montgomery and extend the sphere of his operations into the Punjab. He was on special duty with the Government of India about the years 1860–62, when he investigated forest matters in the North-Western Himalayas and elsewhere. He also assisted Sir Dietrich Brandis, C.I.E., in implementing ideas from German forestry on the rotation and systematic working of forests in Bengal. His work led to the establishment of the Forest Department of India. With Sir Dietrich Brandis, he was the first Commissioner for the Conservancy of Forests. In 1867 he was appointed Inspector-General of Forests and he retired in 1869.[4]

Cleghorn believed that the state had to take the main role in preserving forests as he had seen the denudation of the teak forests of Burma by private businesses.[4]

Later years

Cleghorn left India in 1869 but continued to be an adviser to the Secretary of State for India and played a role in the selection of candidates for the Indian Forest Service.[4] A member of the Edinburgh Botanical Society since 1839, he was elected president of the Society in 1868–69 (succeeded by Walter Elliot).[18] He was elected president of the Scottish Arboricultural Society in 1872, and subsequently played an instrumental role in the establishment of a lectureship in Forestry in Edinburgh University.[19][20][21] Cleghorn also gave his opinions to the Select Committee of the House of Commons in 1885 on the topic of forestry education in Britain.[22]

Cleghorn wrote the entries on "Arboriculture" and "Forests and Forest Administration" in the 9th edition of Encyclopædia Britannica (v. 9:397–408). He also made a study of the agriculture and botany of Malta and Sicily in 1868.[23]

Robert Wight dedicated a genus, Cleghornia, to Cleghorn in 1850, "a zealous cultivator of Botany, but more especially directing his attention to Medical Botany".[24]

He died at Stravithie Castle, near the village of Dunino west of St Andrews, Fife, on 16 May 1895. The heir to the property was the son of his sister who was married to Alexander Sprot of Garnkirk.[5]

Notes

- ↑ Noltie (2016):236.

- ↑ Addison, W. Innes (1901). The Snell Exhibitions. Glasgow: James MacLehose & Sons. p. 79.

- ↑ Rogers, Charles (1889). The Book of Robert Burns. Volume 1. Edinburgh: Grampian Club. p. 124.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Das, Pallavi (2005). "Hugh Cleghorn and Forest Conservancy in India". Environment and History. 11 (1): 55–82. doi:10.3197/0967340053306149.

- 1 2 3 "Death of Dr H.F.C. Cleghorn". Evening Telegraph. British Newspaper Archive. 17 May 1895. p. 2. Retrieved 9 July 2014. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Noltie (2016):22. [Note that Cleghorn mistakenly credited Hooker jr.]

- ↑ "Principal Sir William Muir and the Botanic Gardens". Edinburgh Evening News. 8 August 1888. Retrieved 28 October 2014 – via British Newspaper Archive. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Cleghorn, H. (1869). "Presidential address". Transactions of the Botanical Society of Edinburgh. 10: 261–277. doi:10.1080/03746607009468692.

- ↑ "Presentation to Hugh Cleghorn of Stravithie". Transactions of the Royal Scottish Arboricultural Society. 12: 198–205. 1890.

- ↑ Cleghorn, Hugh F. C. (1853). "On the Hedge Plants of India, and the conditions which adapt them for special purposes and particular localities". Transactions of the Botanical Society of Edinburgh. 4: 1–4, 83–100. doi:10.1080/03746605309467595.

- ↑ "Highland & Agricultural Society". Inverness Courier. 17 July 1851. p. 4 – via British Newspaper Archive. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Cleghorn, Hugh (1856). "Notulae Botanicae No.1. On the sand-binding plants of the Madras Beach". Madras Journal of Literature and Science: 85–90.

- ↑ Brandis, Dietrich (1888). "Dr Cleghorn's services to Indian Botany". Indian Forester. 4: 14.

- ↑ "Marriages". Dundee Courier. British Newspaper Archive. 10 August 1861. p. 1. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Cleghorn, M.D. (1861). "Expedition to the Higher Ranges of the Anamalai Hills, Coimbatore, in 1858". Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 22: 579–587. doi:10.1017/s0080456800031422.

- ↑ Cleghorn, Hugh Francis Clarke (1861). The Forests and Gardens of South India. London: W. H. Allen.

- ↑ Brandis, D. (1888). "Dr Cleghorn's Services to Indian Forestry". Transactions of the Royal Scottish Arboricultural Society. 12: 87–93.

- ↑ The Botanical Society of Edinburgh 1836–1936. Edinburgh: Botanical Society of Edinburgh. 1936. p. 15.

- ↑ "Obituary: Hugh F. C. Cleghorn, M. D., LL. D., F. R. S. E.". The Geographical Journal. 6 (1): 83. 1895. JSTOR 1773955.

- ↑ Brandis, Dietrich (1888). "The Proposed School of Forestry". Transactions of the Royal Scottish Arboricultural Society. 12: 65–77.

- ↑ Cleghorn, H (1885). "President's address-Delivered at the Thirty-second Annual meeting". Transactions of the Scottish Arboricultural Society. 11 (2): 115–118.

- ↑ "Report of the Select Committee of the House of Commons, 1885, on Forestry". Transactions of the Scottish Arboricultural Society. 11 (2): 119–154. 1885.

- ↑ Cleghorn, H. (1869). "Notes on the Botany and Agriculture of Malta and Sicily". Transactions of the Scottish Arboricultural Society. 11 (1): 106–139.

- ↑ Wight, Robert (1850). Icones Plantarum Indiae Orientalis or Figures of Indian Plants. Volume IV part 2. Madras: Franck & Co. p. 5.

- ↑ IPNI. Cleghorn.

Cited references

- Noltie, Henry J. (2016). Indian Forester, Scottish Laird. The Botanical Lives of Hugh Cleghorn of Stravithie. Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. ISBN 9781910877104.

External links

- Works by or about Hugh Cleghorn at Internet Archive

- Cleghorn, H. (1864) Report upon the Forests of the Punjab and the western Himalaya. Thomason Civil Engineering College, Roorkee.

- Cleghorn, H. (1858) Memorandum upon the pauchontee or Indian gutta tree of the western coast. Government of Madras