Human cloning

Human cloning is the creation of a genetically identical copy of a human. The term is generally used to refer to artificial human cloning, which is the reproduction of human cells and tissue. It does not refer to the natural conception and delivery of identical twins. The possibility of human cloning has raised controversies. These ethical concerns have prompted several nations to pass laws regarding human cloning and its legality.

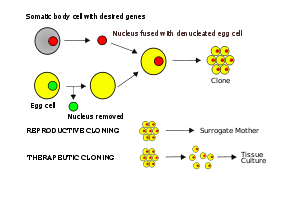

Two commonly discussed types of theoretical human cloning are: therapeutic cloning and reproductive cloning. Therapeutic cloning would involve cloning cells from a human for use in medicine and transplants, and is an active area of research, but is not in medical practice anywhere in the world, as of July 2016. Two common methods of therapeutic cloning that are being researched are somatic-cell nuclear transfer and, more recently, pluripotent stem cell induction. Reproductive cloning would involve making an entire cloned human, instead of just specific cells or tissues.

History

Although the possibility of cloning humans had been the subject of speculation for much of the 20th century, scientists and policy makers began to take the prospect seriously in the mid-1960s.

Nobel Prize-winning geneticist Joshua Lederberg advocated cloning and genetic engineering in an article in The American Naturalist in 1966 and again, the following year, in The Washington Post.[1] He sparked a debate with conservative bioethicist Leon Kass, who wrote at the time that "the programmed reproduction of man will, in fact, dehumanize him." Another Nobel Laureate, James D. Watson, publicized the potential and the perils of cloning in his Atlantic Monthly essay, "Moving Toward the Clonal Man", in 1971.[2]

With the cloning of a sheep known as Dolly in 1996 by somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT), the idea of human cloning became a hot debate topic.[3] Many nations outlawed it, while a few scientists promised to make a clone within the next few years. The first hybrid human clone was created in November 1998, by Advanced Cell Technology. It was created using SCNT - a nucleus was taken from a man's leg cell and inserted into a cow's egg from which the nucleus had been removed, and the hybrid cell was cultured, and developed into an embryo. The embryo was destroyed after 12 days.[4]

In 2004 and 2005, Hwang Woo-suk, a professor at Seoul National University, published two separate articles in the journal Science claiming to have successfully harvested pluripotent, embryonic stem cells from a cloned human blastocyst using somatic-cell nuclear transfer techniques. Hwang claimed to have created eleven different patent-specific stem cell lines. This would have been the first major breakthrough in human cloning.[5] However, in 2006 Science retracted both of his articles on clear evidence that much of his data from the experiments was fabricated.[6]

In January 2008, Dr. Andrew French and Samuel Wood of the biotechnology company Stemagen announced that they successfully created the first five mature human embryos using SCNT. In this case, each embryo was created by taking a nucleus from a skin cell (donated by Wood and a colleague) and inserting it into a human egg from which the nucleus had been removed. The embryos were developed only to the blastocyst stage, at which point they were studied in processes that destroyed them. Members of the lab said that their next set of experiments would aim to generate embryonic stem cell lines; these are the "holy grail" that would be useful for therapeutic or reproductive cloning.[7][8]

In 2011, scientists at the New York Stem Cell Foundation announced that they had succeeded in generating embryonic stem cell lines, but their process involved leaving the oocyte's nucleus in place, resulting in triploid cells, which would not be useful for cloning.[9][10][11]

In 2013, a group of scientists led by Shoukhrat Mitalipov published the first report of embryonic stem cells created using SCNT. In this experiment, the researchers developed a protocol for using SCNT in human cells, which differs slightly from the one used in other organisms. Four embryonic stem cell lines from human fetal somatic cells were derived from those blastocysts. All four lines were derived using oocytes from the same donor, ensuring that all mitochondrial DNA inherited was identical.[9] A year later, a team led by Robert Lanza at Advanced Cell Technology reported that they had replicated Mitalipov's results and further demonstrated the effectiveness by cloning adult cells using SCNT.[3][12]

Methods

Somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT)

In somatic cell nuclear transfer ("SCNT"), the nucleus of a somatic cell is taken from a donor and transplanted into a host egg cell, which had its own genetic material removed previously, making it an enucleated egg. After the donor somatic cell genetic material is transferred into the host oocyte with a micropipette, the somatic cell genetic material is fused with the egg using an electric current. Once the two cells have fused, the new cell can be permitted to grow in a surrogate or artificially.[13] This is the process that was used to successfully clone Dolly the sheep (see section on History in this article).[3]

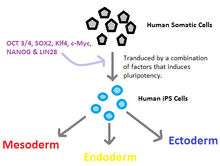

Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs)

Creating induced pluripotent stem cells ("iPSCs") is a long and inefficient process. Pluripotency refers to a stem cell that has the potential to differentiate into any of the three germ layers: endoderm (interior stomach lining, gastrointestinal tract, the lungs), mesoderm (muscle, bone, blood, urogenital), or ectoderm (epidermal tissues and nervous system).[14] A specific set of genes, often called "reprogramming factors", are introduced into a specific adult cell type. These factors send signals in the mature cell that cause the cell to become a pluripotent stem cell. This process is highly studied and new techniques are being discovered frequently on how to better this induction process.

Depending on the method used, reprogramming of adult cells into iPSCs for implantation could have severe limitations in humans. If a virus is used as a reprogramming factor for the cell, cancer-causing genes called oncogenes may be activated. These cells would appear as rapidly dividing cancer cells that do not respond to the body's natural cell signaling process. However, in 2008 scientists discovered a technique that could remove the presence of these oncogenes after pluripotency induction, thereby increasing the potential use of iPSC in humans.[15]

Comparing SCNT to reprogramming

Both the processes of SCNT and iPSCs have benefits and deficiencies. Historically, reprogramming methods were better studied than SCNT derived embryonic stem cells (ESCs).[9] However, more recent studies have put more emphasis on developing new procedures for SCNT-ESCs. The major advantage of SCNT over iPSCs at this time is the speed with which cells can be produced. iPSCs derivation takes several months while SCNT would take a much shorter time, which could be important for medical applications. New studies are working to improve the process of iPSC in terms of both speed and efficiency with the discovery of new reprogramming factors in oocytes. Another advantage SCNT could have over iPSCs is its potential to treat mitochondrial disease, as it utilizes a donor oocyte.[9] No other advantages are known at this time in using stem cells derived from one method over stem cells derived from the other.[16]

Uses, actual and potential

Work on cloning techniques has advanced our basic understanding of developmental biology in humans. Observing human pluripotent stem cells grown in culture provides great insight into human embryo development, which otherwise cannot be seen. Scientists are now able to better define steps of early human development. Studying signal transduction along with genetic manipulation within the early human embryo has the potential to provide answers to many developmental diseases and defects. Many human-specific signaling pathways have been discovered by studying human embryonic stem cells. Studying developmental pathways in humans has given developmental biologists more evidence toward the hypothesis that developmental pathways are conserved throughout species.[17]

iPSCs and cells created by SCNT are useful for research into the causes of disease, and as model systems used in drug discovery.[18][19]

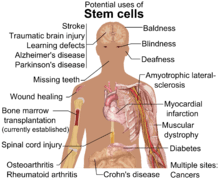

Cells produced with SCNT, or iPSCs could eventually be used in stem cell therapy,[20] or to create organs to be used in transplantation, known as regenerative medicine. Stem cell therapy is the use of stem cells to treat or prevent a disease or condition. Bone marrow transplantation is a widely used form of stem cell therapy.[21] No other forms of stem cell therapy are in clinical use at this time. Research is underway to potentially use stem cell therapy to treat heart disease, diabetes, and spinal cord injuries.[22][23] Regenerative medicine is not in clinical practice, but is heavily researched for its potential uses. This type of medicine would allow for autologous transplantation, thus removing the risk of organ transplant rejection by the recipient.[24] For instance, a person with liver disease could potentially have a new liver grown using their same genetic material and transplanted to remove the damaged liver.[25] In current research, human pluripotent stem cells have been promised as a reliable source for generating human neurons, showing the potential for regenerative medicine in brain and neural injuries.[26]

Ethical implications

In bioethics, the ethics of cloning refers to a variety of ethical positions regarding the practice and possibilities of cloning, especially human cloning. While many of these views are religious in origin, the questions raised by cloning are faced by secular perspectives as well. Human therapeutic and reproductive cloning are not commercially used; animals are currently cloned in laboratories and in livestock production.

Advocates support development of therapeutic cloning in order to generate tissues and whole organs to treat patients who otherwise cannot obtain transplants,[27] to avoid the need for immunosuppressive drugs,[28] and to stave off the effects of aging.[29] Advocates for reproductive cloning believe that parents who cannot otherwise procreate should have access to the technology.[30]

Opposition to therapeutic cloning mainly centers around the status of embryonic stem cells, which has connections with the abortion debate.[31]

Some opponents of reproductive cloning have concerns that technology is not yet developed enough to be safe - for example, the position of the American Association for the Advancement of Science as of 2014,[32] while others emphasize that reproductive cloning could be prone to abuse (leading to the generation of humans whose organs and tissues would be harvested),[33][34] and have concerns about how cloned individuals could integrate with families and with society at large.[35][36]

Religious groups are divided, with some opposing the technology as usurping God's (in monotheistic traditions) place and, to the extent embryos are used, destroying a human life; others support therapeutic cloning's potential life-saving benefits.[37][38]

Current law

In 2015 it was reported that about 70 countries had banned human cloning.[39]

Australia

Australia has prohibited human cloning,[40] though as of December 2006, a bill legalizing therapeutic cloning and the creation of human embryos for stem cell research passed the House of Representatives. Within certain regulatory limits, and subject to the effect of state legislation, therapeutic cloning is now legal in some parts of Australia.[41]

Canada

Canadian law prohibits the following: cloning humans, cloning stem cells, growing human embryos for research purposes, and buying or selling of embryos, sperm, eggs or other human reproductive material.[42] It also bans making changes to human DNA that would pass from one generation to the next, including use of animal DNA in humans. Surrogate mothers are legally allowed, as is donation of sperm or eggs for reproductive purposes. Human embryos and stem cells are also permitted to be donated for research.

There have been consistent calls in Canada to ban human reproductive cloning since the 1993 Report of the Royal Commission on New Reproductive Technologies. Polls have indicated that an overwhelming majority of Canadians oppose human reproductive cloning, though the regulation of human cloning continues to be a significant national and international policy issue. The notion of "human dignity" is commonly used to justify cloning laws. The basis for this justification is that reproductive human cloning necessarily infringes notions of human dignity.[43][44][45][46]

Colombia

Human cloning is prohibited in Article 133 of the Colombian Penal Code.[47]

European Union

The European Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine prohibits human cloning in one of its additional protocols, but this protocol has been ratified only by Greece, Spain and Portugal. The Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union explicitly prohibits reproductive human cloning. The charter is legally binding for the institutions of the European Union under the Treaty of Lisbon and for member states of the Union implementing EU law.[48][49]

India

India does not have specific law regarding cloning but has guidelines prohibiting whole human cloning or reproductive cloning. India allows therapeutic cloning and the use of embryonic stem cells for research proposes.[50][51]

Serbia

Human cloning is explicitly prohibited in Article 24, "Right to Life" of the 2006 Constitution of Serbia.[52]

South Africa

In terms of section 39A of the Human Tissue Act 65 of 1983, genetic manipulation of gametes or zygotes outside the human body is absolutely prohibited. A zygote is the cell resulting from the fusion of two gametes; thus the fertilised ovum. Section 39A thus prohibits human cloning.

United Kingdom

On January 14, 2001 the British government passed The Human Fertilisation and Embryology (Research Purposes) Regulations 2001[53] to amend the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 1990 by extending allowable reasons for embryo research to permit research around stem cells and cell nuclear replacement, thus allowing therapeutic cloning. However, on November 15, 2001, a pro-life group won a High Court legal challenge, which struck down the regulation and effectively left all forms of cloning unregulated in the UK. Their hope was that Parliament would fill this gap by passing prohibitive legislation.[54][55] Parliament was quick to pass the Human Reproductive Cloning Act 2001 which explicitly prohibited reproductive cloning. The remaining gap with regard to therapeutic cloning was closed when the appeals courts reversed the previous decision of the High Court.[56]

The first license was granted on August 11, 2004 to researchers at the University of Newcastle to allow them to investigate treatments for diabetes, Parkinson's disease and Alzheimer's disease.[57] The Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 2008, a major review of fertility legislation, repealed the 2001 Cloning Act by making amendments of similar effect to the 1990 Act. The 2008 Act also allows experiments on hybrid human-animal embryos.[58]

United Nations

On December 13, 2001, the United Nations General Assembly began elaborating an international convention against the reproductive cloning of humans. A broad coalition of States, including Spain, Italy, the Philippines, the United States, Costa Rica and the Holy See sought to extend the debate to ban all forms of human cloning, noting that, in their view, therapeutic human cloning violates human dignity. Costa Rica proposed the adoption of an international convention to ban all forms of human cloning. Unable to reach a consensus on a binding convention, in March 2005 a non-binding United Nations Declaration on Human Cloning, calling for the ban of all forms of human cloning contrary to human dignity, was adopted.[59][60]

United States

In 1998, 2001, 2004, 2005, and 2007, the United States House of Representatives voted whether to ban all human cloning, both reproductive and therapeutic. Each time, divisions in the Senate over therapeutic cloning prevented either competing proposal (a ban on both forms or reproductive cloning only) from passing. On March 10, 2010 a bill (HR 4808) was introduced with a section banning federal funding for human cloning. Such a law, if passed, would not prevent research from occurring in private institutions (such as universities) that have both private and federal funding. There are currently no federal laws in the United States which ban cloning completely, and any such laws would raise difficult constitutional questions similar to the issues raised by abortion. Fifteen American states (Arkansas, California, Connecticut, Iowa, Indiana, Massachusetts, Maryland, Michigan, North Dakota, New Jersey, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Florida, Georgia, and Virginia) ban reproductive cloning and three states (Arizona, Maryland, and Missouri) prohibit use of public funds for such activities.

In popular culture

Science fiction has used cloning, most commonly and specifically human cloning, due to the fact that it brings up controversial questions of identity.[61][62] Humorous fiction, such as Multiplicity (1996)[63] and the Maxwell Smart feature The Nude Bomb (1980), has featured human cloning.[64] A recurring sub-theme of cloning fiction is the use of clones as a supply of organs for transplantation. Robin Cook's 1997 novel Chromosome 6 is an example of this; it also features genetic manipulation and xenotransplantation.[65]

References

- ↑ Lederberg Joshua (1966). "Experimental Genetics and Human Evolution". The American Naturalist. 100 (915): 519–531. doi:10.1086/282446.

- ↑ Watson, James. "Moving Toward a Clonal Man: Is This What We Want?" The Atlantic Monthly (1971).

- 1 2 3 Park, Alice (April 17, 2014). "Researchers Clone Cells From Two Adult Men". Time. Retrieved April 18, 2014.

- ↑ "Details of hybrid clone revealed". BBC News. June 18, 1999. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ↑ Fischbak, Ruth L., John D. Loike, Janet Mindes, and Columbia Center for New Media Teaching & Learning. The Cloning Scandal of Hwang Woo-Suk, part of the online course, Stem Cells: Biology, Ethics, and Applications

- ↑ Kennedy D (2006). "Responding to fraud". Science. 314 (5804): 1353. doi:10.1126/science.1137840. PMID 17138870.

- ↑ Rick Weiss for the Washington Post January 18, 2008 Mature Human Embryos Created From Adult Skin Cells

- ↑ French AJ, Adams CA, Anderson LS, Kitchen JR, Hughes MR, Wood SH (2008). "Development of human cloned blastocysts following somatic cell nuclear transfer with adult fibroblasts". Stem Cells. 26 (2): 485–93. doi:10.1634/stemcells.2007-0252. PMID 18202077.

- 1 2 3 4 Trounson A, DeWitt ND (2013). "Pluripotent stem cells from cloned human embryos: success at long last". Cell Stem Cell. 12 (6): 636–8. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2013.05.022. PMID 23746970.

- ↑ Noggle S, Fung HL, Gore A, Martinez H, Satriani KC, Prosser R, Oum K, Paull D, Druckenmiller S, Freeby M, Greenberg E, Zhang K, Goland R, Sauer MV, Leibel RL, Egli D (2011). "Human oocytes reprogram somatic cells to a pluripotent state". Nature. 478 (7367): 70–5. doi:10.1038/nature10397. PMID 21979046.

- ↑ Daley GQ, Solbakk JH (2011). "Stem cells: Triple genomes go far". Nature. 478 (7367): 40–1. doi:10.1038/478040a. PMID 21979039.

- ↑ Chung YG, Eum JH, Lee JE, Shim SH, Sepilian V, Hong SW, Lee Y, Treff NR, Choi YH, Kimbrel EA, Dittman RE, Lanza R, Lee DR (2014). "Human somatic cell nuclear transfer using adult cells". Cell Stem Cell. 14 (6): 777–80. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2014.03.015. PMID 24746675.

- ↑ Gilbert, Scott F. (2013-06-30). Developmental Biology (10th ed.). Sinauer Associates, Inc. pp. 32–33. ISBN 9780878939787.

- ↑ Binder, Marc D.; Hirokawa, Nobutaka; Windhorst, Uwe, eds. (2009). Encyclopedia of Neuroscience ([Online-Ausg.] ed.). Berlin: Springer. ISBN 978-3540237358.

- ↑ Kaplan, Karen (March 6, 2009). "Cancer threat removed from stem cells, scientists say". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ Langerova A, Fulka H, Fulka J (2013). "Somatic cell nuclear transfer-derived embryonic stem cell lines in humans: pros and cons". Cell Reprogram. 15 (6): 481–3. doi:10.1089/cell.2013.0054. PMID 24180743.

- ↑ Zhu Z, Huangfu D (2013). "Human pluripotent stem cells: an emerging model in developmental biology". Development. 140 (4): 705–17. doi:10.1242/dev.086165. PMC 3557771

. PMID 23362344.

. PMID 23362344. - ↑ Subba Rao M, Sasikala M, Nageshwar Reddy D (2013). "Thinking outside the liver: induced pluripotent stem cells for hepatic applications". World J. Gastroenterol. 19 (22): 3385–96. doi:10.3748/wjg.v19.i22.3385. PMC 3683676

. PMID 23801830.

. PMID 23801830. - ↑ Tobe BT, Brandel MG, Nye JS, Snyder EY (2013). "Implications and limitations of cellular reprogramming for psychiatric drug development". Exp. Mol. Med. 45: e59. doi:10.1038/emm.2013.124. PMC 3849573

. PMID 24232258.

. PMID 24232258. - ↑ Singec I, Jandial R, Crain A, Nikkhah G, Snyder EY (2007). "The leading edge of stem cell therapeutics". Annu. Rev. Med. 58: 313–28. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.58.070605.115252. PMID 17100553.

- ↑ Bone Marrow Transplantation and Peripheral Blood Stem Cell Transplantation In National Cancer Institute Fact Sheet web site. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2010. Cited August 24, 2010

- ↑ Cell Basics: What are the potential uses of human stem cells and the obstacles that must be overcome before these potential uses will be realized?. In Stem Cell Information World Wide Web site. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2009. cited Sunday, April 26, 2009

- ↑ Cummings BJ, Uchida N, Tamaki SJ, Salazar DL, Hooshmand M, Summers R, Gage FH, Anderson AJ (September 2005). "Human neural stem cells differentiate and promote locomotor recovery in spinal cord-injured mice". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102 (39): 14069–74. doi:10.1073/pnas.0507063102. PMC 1216836

. PMID 16172374.

. PMID 16172374. - ↑ Svendsen CN (2013). "Back to the future: how human induced pluripotent stem cells will transform regenerative medicine". Hum. Mol. Genet. 22 (R1): R32–8. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddt379. PMC 3782070

. PMID 23945396.

. PMID 23945396. - ↑ Booth C, Soker T, Baptista P, Ross CL, Soker S, Farooq U, Stratta RJ, Orlando G (2012). "Liver bioengineering: current status and future perspectives". World J. Gastroenterol. 18 (47): 6926–34. doi:10.3748/wjg.v18.i47.6926. PMC 3531676

. PMID 23322990.

. PMID 23322990. - ↑ Jongkamonwiwat N, Noisa P (2013). "Biomedical and clinical promises of human pluripotent stem cells for neurological disorders". Biomed Res Int. 2013: 656531. doi:10.1155/2013/656531. PMC 3793324

. PMID 24171168.

. PMID 24171168. - ↑ "Cloning Fact Sheet". U.S. Department of Energy Genome Program. 2009-05-11. Archived from the original on 2013-05-02.

- ↑ Kfoury C (2007). "Therapeutic cloning: Promises and issues". McGill Journal of Medicine. 10 (2): 112–20. PMC 2323472

. PMID 18523539.

. PMID 18523539. - ↑ de Grey, Aubrey; Rae, Michael (2007). Ending Aging: The Rejuvenation Breakthroughs that Could Reverse Human Aging in Our Lifetime. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-36706-6.

- ↑ Staff (August 10, 2001). "In the news: Antinori and Zavos". Times Higher Education.

- ↑ Kfoury C (2007). "Therapeutic cloning: promises and issues". Mcgill J Med. 10 (2): 112–20. PMC 2323472

. PMID 18523539.

. PMID 18523539. - ↑ "AAAS Statement on Human Cloning".

- ↑ McGee, G. (October 2011). "Primer on Ethics and Human Cloning". American Institute of Biological Sciences.

- ↑ "Universal Declaration on the Human Genome and Human Rights". UNESCO. 1997-11-11. Retrieved 2008-02-27.

- ↑ McGee, Glenn (2000). The Perfect Baby: Parenthood in the New World of Cloning and Genetics (2nd ed.). Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-8476-9758-4.

- ↑ Havstad, Joyce. "Human Reproductive Cloning: A Conflict of Liberties". San Diego State University.

- ↑ Sullivan, Bob (November 26, 2003). "Religions reveal little consensus on cloning". MSNBC. Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- ↑ Sims Bainbridge, William (October 2003). "Religious Opposition to Cloning". Journal of Evolution and Technology. 13.

- ↑ Cohen, Haley (31 July 2015). "How Champion-Pony Clones Have Transformed the Game of Polo". Vanity Fair. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ↑ "Prohibition of Human Cloning for Reproduction Act 2002". NHMRC.gov.au. Australia: National Health and Medical Research Council. 12 June 2007.

- ↑ "Research cloning - Legal Aspects". Deutches Referenzzentrum fur Ethik in den Biowissenschaften. April 2014. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ↑ Philipkoski, Kristen (17 March 2004). "Canada Closes Door on Cloning". Wired.

- ↑ Matthews, Kristin. "Overview of World Human Cloning Policies". Connexions. Rice University. Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- ↑ Baylis, Francoise. "Canada Bans Human Cloning". The Hastings Center Report. republished at Questia.com. Retrieved 7 December 2011.

- ↑ Philipkoski, Kristen (March 17, 2004). "Canada Closes Door on Cloning". Wired.com.

- ↑ "Regulating and treating conception problems". CBC.ca. December 21, 2010. Retrieved 7 December 2011.

- ↑ "Ley 599 de 2000 (Julio 24) Por la cual se expide el Código Penal" [Law 599 of 2000 (July 24) which issued the Penal Code]. alcaldiabogota.gov.co (in Spanish). Bogota, Colombia: Bogota Mayoral Office. July 24, 2000. Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- ↑ Treaty of Lisbon (2007/C 306/01) Article 6 (1)

- ↑ "EU Charter of Fundamental Rights". Europa (web portal). Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- ↑ Bagla, Pallava (Jun 24, 2009). "Should India ban human cloning?". New Delhi: NDTV. Retrieved Apr 18, 2014.

- ↑ "Cloning Ethical Policies on the Human Genome, Genetic Research and Services [India]". Genetics & Public Policy Center.

- ↑ "Constitution of the Republic of Serbia, II Human and Minority Rights and Freedoms". Government of Serbia. Retrieved May 15, 2013.

- ↑ Text of the Human Fertilisation and Embryology (Research Purposes) Regulations 2001 (No. 188) as originally enacted or made within the United Kingdom, from legislation.gov.uk

- ↑ SD Pattinson (2006), Medical Law and Ethics, Sweet & Maxwell, ISBN 978-0-421-88950-7

- ↑ "Campaigners win cloning challenge". London: BBC News. 15 November 2001. Retrieved 2008-09-06.

- ↑ "Lords uphold cloning law". London: BBC News. 13 March 2003.

- ↑ "HFEA grants the first therapeutic cloning licence for research". HFEA. 11 August 2004. Retrieved 2008-09-06.

- ↑ "MPs support embryology proposals". London: BBC News. 23 October 2008.

- ↑ "United Nations Declaration on Human Cloning". Bio Etica Web. March 16, 2005.

- ↑ "Ad Hoc Committee on an International Convention against the Reproductive Cloning of Human Beings". United Nations. 18 May 2005. Retrieved 2007-01-28.

- ↑ Hopkins, Patrick. "How Popular media represent cloning as an ethical problem". 28. The Hastings Center: 6–13. JSTOR 3527566.

- ↑ De La Cruz, Yvonne A. "Science Fiction Storytelling and Identity: Seeing the Human Through Android Eyes" (PDF). CSUStan.edu. California State University, Stanislaus. Retrieved 2012-08-19.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger. "Multiplicity". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- ↑ Douglass, Todd Jr. (July 12, 2008). "The Nude Bomb". DVDTalk.com. Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- ↑ tech-writer (September 30, 2005). "A Chiller Thriller". Retrieved September 15, 2016.

Further reading

- Araujo, Robert John, "The UN Declaration on Human Cloning: a survey and assessment of the debate," 7 The National Catholic Bioethics Quarterly 129 - 149 (2007).

- Oregon Health & Science University. "Human skin cells converted into embryonic stem cells: First time human stem cells have been produced via nuclear transfer." ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 15 May 2013. .

External links

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Genes, Technology and Policy |

- "Variations and voids: the regulation of human cloning around the world" academic article by S. Pattinson & T. Caulfield

- Moving Toward the Clonal Man

- Should We Really Fear Reproductive Human Cloning

- United Nation declares law against cloning.

- General Assembly Adopts United Nations Declaration on Human Cloning By Vote of 84-34-37

- Cloning Fact Sheet

- How Human Cloning Will Work