Hydronium

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

oxonium | |||

| Other names

hydronium ion | |||

| Identifiers | |||

| 13968-08-6 | |||

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image | ||

| ChEBI | CHEBI:29412 | ||

| ChemSpider | 109935 | ||

| PubChem | 123332 | ||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| H3O+ | |||

| Molar mass | 19.02 g/mol | ||

| Acidity (pKa) | −1.7 | ||

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |||

| | |||

| Infobox references | |||

In chemistry, hydronium is the common name for the aqueous cation H

3O+

, the type of oxonium ion produced by protonation of water. It is the positive ion present when an Arrhenius acid is dissolved in water, as Arrhenius acid molecules in solution give up a proton (a positive hydrogen ion, H+) to the surrounding water molecules (H2O).

Determination of pH

It is the presence of hydronium ion relative to hydroxide that determines a solution's pH. The molecules in pure water auto-dissociate into hydronium and hydroxide ions in the following equilibrium:

- 2 H

2O ⇌ OH−

+ H

3O+

In pure water, there is an equal number of hydroxide and hydronium ions, so it is a neutral solution. At 25 °C, water has a pH of 7 (this varies when the temperature changes: see self-ionization of water). A pH value less than 7 indicates an acidic solution, and a pH value more than 7 indicates a basic solution.

Nomenclature

According to IUPAC nomenclature of organic chemistry, the hydronium ion should be referred to as oxonium.[1] Hydroxonium may also be used unambiguously to identify it. A draft IUPAC proposal also recommends the use of oxonium and oxidanium in organic and inorganic chemistry contexts, respectively.

An oxonium ion is any ion with a trivalent oxygen cation. For example, a protonated hydroxyl group is an oxonium ion, but not a hydronium.

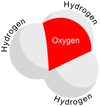

Structure

Since O+

and N have the same number of electrons, H

3O+

is isoelectronic with ammonia. As shown in the images above, H

3O+

has a trigonal pyramid geometry with the oxygen atom at its apex. The H–O–H bond angle is approximately 113°,[2] and the center of mass is very close to the oxygen atom. Because the base of the pyramid is made up of three identical hydrogen atoms, the H

3O+

molecule's symmetric top configuration is such that it belongs to the C3v point group. Because of this symmetry and the fact that it has a dipole moment, the rotational selection rules are ΔJ = ±1 and ΔK = 0. The transition dipole lies along the c-axis and, because the negative charge is localized near the oxygen atom, the dipole moment points to the apex, perpendicular to the base plane.

Acids and acidity

Hydronium is the cation that forms from water in the presence of hydrogen ions. These hydrons do not exist in a free state: they are extremely reactive and are solvated by water. An acidic solute is generally the source of these hydrons; however, hydroniums exist even in pure water. This special case of water reacting with water to produce hydronium (and hydroxide) ions is commonly known as the self-ionization of water. The resulting hydronium ions are few and short-lived. pH is a measure of the relative activity of hydronium and hydroxide ions in aqueous solutions. In acidic solutions, hydronium is the more active, its excess proton being readily available for reaction with basic species.

Hydronium is very acidic: at 25 °C, its pKa is −1.7. It is the most acidic species that can exist in water (assuming sufficient water for dissolution): any stronger acid will ionize and protonate a water molecule to form hydronium. The acidity of hydronium is the implicit standard used to judge the strength of an acid in water: strong acids must be better proton donors than hydronium, otherwise a significant portion of acid will exist in a non-ionized state. Unlike hydronium in neutral solutions that result from water's autodissociation, hydronium ions in acidic solutions are long-lasting and concentrated, in proportion to the strength of the dissolved acid.

pH was originally conceived to be a measure of the hydrogen ion concentration of aqueous solution.[3] We now know that virtually all such free protons quickly react with water to form hydronium; acidity of an aqueous solution is therefore more accurately characterized by its hydronium concentration. In organic syntheses, such as acid catalyzed reactions, the hydronium ion (H

3O+

) can be used interchangeably with the H+ ion; choosing one over the other has no significant effect on the mechanism of reaction.

Solvation

Researchers have yet to fully characterize the solvation of hydronium ion in water, in part because many different meanings of solvation exist. A freezing-point depression study determined that the mean hydration ion in cold water is approximately H

3O+

(H

2O)

6:[4] on average, each hydronium ion is solvated by 6 water molecules which are unable to solvate other solute molecules.

Some hydration structures are quite large: the H

3O+

(H

2O)

20 magic ion number structure (called magic because of its increased stability with respect to hydration structures involving a comparable number of water molecules – this is a similar usage of the word magic as in nuclear physics) might place the hydronium inside a dodecahedral cage.[5] However, more recent ab initio method molecular dynamics simulations have shown that, on average, the hydrated proton resides on the surface of the H

3O+

(H

2O)

20 cluster.[6] Further, several disparate features of these simulations agree with their experimental counterparts suggesting an alternative interpretation of the experimental results.

Two other well-known structures are the Zundel cations and Eigen cations. The Eigen solvation structure has the hydronium ion at the center of an H

9O+

4 complex in which the hydronium is strongly hydrogen-bonded to three neighbouring water molecules.[7] In the Zundel H

5O+

2 complex the proton is shared equally by two water molecules in a symmetric hydrogen bond.[8] Recent work indicates that both of these complexes represent ideal structures in a more general hydrogen bond network defect.[9]

Isolation of the hydronium ion monomer in liquid phase was achieved in a nonaqueous, low nucleophilicity superacid solution (HF-SbF

5SO

2). The ion was characterized by high resolution 17

O nuclear magnetic resonance.[10]

A 2007 calculation of the enthalpies and free energies of the various hydrogen bonds around the hydronium cation in liquid protonated water[11] at room temperature and a study of the proton hopping mechanism using molecular dynamics showed that the hydrogen-bonds around the hydronium ion (formed with the three water ligands in the first solvation shell of the hydronium) are quite strong compared to those of bulk water.

A new model was proposed by Stoyanov[12] based on infrared spectroscopy in which the proton exists as an H

13O+

6 ion. The positive charge is thus delocalized over 6 water molecules.

Solid hydronium salts

For many strong acids, it is possible to form crystals of their hydronium salt that are relatively stable. These salts are sometimes called acid monohydrates. As a rule, any acid with an ionization constant of 109 or higher may do this. Acids whose ionization constant is below 109 generally cannot form stable H

3O+

salts. For example, hydrochloric acid has an ionization constant of 107, and mixtures with water at all proportions are liquid at room temperature. However, perchloric acid has an ionization constant of 1010, and if liquid anhydrous perchloric acid and water are combined in a 1:1 molar ratio, solid hydronium perchlorate forms.

The hydronium ion also forms stable compounds with the carborane superacid H(CB

11H(CH

3)

5Br

6).[13] X-ray crystallography shows a C3v symmetry for the hydronium ion with each proton interacting with a bromine atom each from three carborane anions 320 pm apart on average. The [H

3O][H(CB

11HCl

11)] salt is also soluble in benzene. In crystals grown from a benzene solution the solvent co-crystallizes and a H

3O · (benzene)3 cation is completely separated from the anion. In the cation three benzene molecules surround hydronium forming pi-cation interactions with the hydrogen atoms. The closest (non-bonding) approach of the anion at chlorine to the cation at oxygen is 348 pm.

There are also many examples of hydrated hydronium ions known, such as the H

5O+

2 ion in HCl·2H

2O, the H

7O+

3 and H

9O+

4 ions both found in HBr·4H

2O.[14]

Interstellar H3O+

Motivation for study

Hydronium is an abundant molecular ion in the interstellar medium and is found in diffuse[15] and dense[16] molecular clouds as well as the plasma tails of comets.[17] Interstellar sources of hydronium observations include the regions of Sagittarius B2, Orion OMC-1, Orion BN–IRc2, Orion KL, and the comet Hale–Bopp.

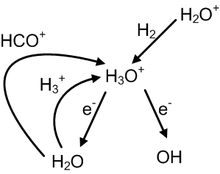

Interstellar hydronium is formed by a chain of reactions started by the ionization of H

2 into H+

2 by cosmic radiation.[18] H

3O+

can produce either OH−

or H

2O through dissociative recombination reactions, which occur very quickly even at the low (≥10 K) temperatures of dense clouds.[19] This leads to hydronium playing a very important role in interstellar ion-neutral chemistry.

Astronomers are especially interested in determining the abundance of water in various interstellar climates due to its key role in the cooling of dense molecular gases through radiative processes.[20] However, H2O does not have many favorable transitions for ground based observations.[21] Although observations of HDO (the deuterated version of water[22]) could potentially be used for estimating H2O abundances, the ratio of HDO to H

2O is not known very accurately.[21]

Hydronium, on the other hand, has several transitions that make it a superior candidate for detection and identification in a variety of situations.[21] This information has been used in conjunction with laboratory measurements of the branching ratios of the various H

3O+

dissociative recombination reactions[19] to provide what are believed to be relatively accurate OH−

and H2O abundances without requiring direct observation of these species.[23][24]

Interstellar chemistry

As mentioned previously, H

3O+

is found in both diffuse and dense molecular clouds. By applying the reaction rate constants (α, β, and γ) corresponding to all of the currently available characterized reactions involving H

3O+

, it is possible to calculate k(T) for each of these reactions. By multiplying these k(T) by the relative abundances of the products, the relative rates (in cm3/s) for each reaction at a given temperature can be determined. These relative rates can be made in absolute rates by multiplying them by the [H

2]2.[25] By assuming T = 10 K for a dense cloud and T = 50 K for a diffuse cloud, the results indicate that most dominant formation and destruction mechanisms were the same for both cases. It should be mentioned that the relative abundances used in these calculations correspond to TMC-1, a dense molecular cloud, and that the calculated relative rates are therefore expected to be more accurate at T = 10 K. The three fastest formation and destruction mechanisms are listed in the table below, along with their relative rates. Note that the rates of these six reactions are such that they make up approximately 99% of hydronium ion's chemical interactions under these conditions.[17] Finally, it should also be noted that all three destruction mechanisms in the table below are classified as dissociative recombination reactions.

3O+

in the interstellar medium (specifically, dense clouds).

| Reaction | Type | Relative rate (cm3/s) at 10 K | Relative rate (cm3/s) at 50 K |

|---|---|---|---|

| H 2 + H 2O+ → H 3O+ + H |

Formation | 2.97×10−22 | 2.97×10−22 |

| H 2O + HCO+ → CO + H 3O+ |

Formation | 4.52×10−23 | 4.52×10−23 |

| H+ 3 + H 2O → H 3O+ + H 2 |

Formation | 3.75×10−23 | 3.75×10−23 |

| H 3O+ + e− → OH + H + H |

Destruction | 2.27×10−22 | 1.02×10−22 |

| H 3O+ + e− → H 2O + H |

Destruction | 9.52×10−23 | 4.26×10−23 |

| H 3O+ + e− → OH + H 2 |

Destruction | 5.31×10−23 | 2.37×10−23 |

It is also worth noting that the relative rates for the formation reactions in the table above are the same for a given reaction at both temperatures. This is due to the reaction rate constants for these reactions having β and γ constants of 0, resulting in k = α which is independent of temperature.

Since all three of these reactions produce either H

2O or OH, these results reinforce the strong connection between their relative abundances and that of H

3O+

. The rates of these six reactions are such that they make up approximately 99% of hydronium ion's chemical interactions under these conditions.

Astronomical detections

As early as 1973 and before the first interstellar detection, chemical models of the interstellar medium (the first corresponding to a dense cloud) predicted that hydronium was an abundant molecular ion and that it played an important role in ion-neutral chemistry.[26] However, before an astronomical search could be underway there was still the matter of determining hydronium's spectroscopic features in the gas phase, which at this point were unknown. The first studies of these characteristics came in 1977,[27] which was followed by other, higher resolution spectroscopy experiments. Once several lines had been identified in the laboratory, the first interstellar detection of H3O+ was made by two groups almost simultaneously in 1986.[16][21] The first, published in June 1986, reported observation of the Jvt

K = 1−

1 − 2+

1 transition at 307192.41 MHz in OMC-1 and Sgr B2. The second, published in August, reported observation of the same transition toward the Orion-KL nebula.

These first detections have been followed by observations of a number of additional H3O+ transitions. The first observations of each subsequent transition detection are given below in chronological order:

In 1991, the 3+

2 − 2−

2 transition at 364797.427 MHz was observed in OMC-1 and Sgr B2.[28] One year later, the 3+

0 − 2−

0 transition at 396272.412 MHz was observed in several regions, the clearest of which was the W3 IRS 5 cloud.[24]

The first far-IR 4−

3 − 3+

3 transition at 69.524 µm (4.3121 THz) was made in 1996 near Orion BN-IRc2.[29] In 2001, three additional transitions of H3O+ in were observed in the far infrared in Sgr B2; 2−

1 − 1+

1 transition at 100.577 µm (2.98073 THz), 1−

1 − 1+

1 at 181.054 µm (1.65582 THz) and 2−

0 − 1+

0 at 100.869 µm (2.9721 THz).[30]

See also

- Hydron (hydrogen cation)

- Hydride

- Hydrogen anion

- Hydrogen ion

- Proton

References

- ↑ Mononuclear parent onium ions. IUPAC

- ↑ Jian Tang and Takeshi Oka (1999). "Infrared spectroscopy of H

3O+

: the v1 fundamental band". J. Mol. Spectrosc. 196 (1): 120–130. Bibcode:1999JMoSp.196..120T. doi:10.1006/jmsp.1999.7844. PMID 10361062. - ↑ Sorensen, S. P. L. (1909). "Ueber die Messung und die Bedeutung der Wasserstoffionenkonzentration bei enzymatischen Prozessen". Biochem. Zeitschr. 21: 131–304.

- ↑ Zavitsas, A. A. (2001). "Properties of water solutions of electrolytes and nonelectrolytes". J. Phys. Chem. B. 105 (32): 7805–7815. doi:10.1021/jp011053l.

- ↑ Hulthe, G.; Stenhagen, G.; Wennerström, O.; Ottosson, C-H. (1997). "Water cluster studied by electrospray mass spectrometry". J. Chromatogr. A. 512: 155–165. doi:10.1016/S0021-9673(97)00486-X.

- ↑ Iyengar, S. S.; Petersen, M. K.; Burnham, C. J.; Day, T. J. F.; Voth, G. A.; Voth, G. A. (2005). "The Properties of Ion-Water Clusters. I. The Protonated 21-Water Cluster" (PDF). J. Chem. Phys. 123 (8): 084309. Bibcode:2005JChPh.123h4309I. doi:10.1063/1.2007628. PMID 16164293.

- ↑ Zundel, G.; Metzger, H. (1968). "Energiebänder der tunnelnden Überschuß-Protonen in flüssigen Säuren. Eine IR-spektroskopische Untersuchung der Natur der Gruppierungen H

5O+

2". Z. Phys. Chem. 58 (5_6): 225–245. doi:10.1524/zpch.1968.58.5_6.225. - ↑ Wicke, E.; Eigen, M.; Ackermann, Th (1954). "Über den Zustand des Protons (Hydroniumions) in wäßriger Lösung". Z. Phys. Chem. 1 (5_6): 340–364. doi:10.1524/zpch.1954.1.5_6.340.

- ↑ Marx, D.; Tuckerman, M. E.; Hutter, J.; Parrinello, M. (1999). "The nature of the hydrated excess proton in water". Nature. 397 (6720): 601–604. Bibcode:1999Natur.397..601M. doi:10.1038/17579.

- ↑ Mateescu, G. D.; Benedikt, G. M. (1979). "Water and related systems. 1. The hydronium ion (H

3O+

). Preparation and characterization by high resolution oxygen-17 nuclear magnetic resonance". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 101 (14): 3959–3960. doi:10.1021/ja00508a040. - ↑ Markovitch, O.; Agmon, N. (2007). "Structure and Energetics of the Hydronium Hydration Shells" (PDF). The Journal of Physical Chemistry A. 111 (12): 2253–6. doi:10.1021/jp068960g. PMID 17388314.

- ↑ Stoyanov, E. S.; Stoyanova, I. V.; Reed, C. A. (2010). "The Structure of the Hydrogen Ion (H+

aq) in Water". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 132 (5): 1484–5. doi:10.1021/ja9101826. PMC 2946644 . PMID 20078058.

. PMID 20078058. - ↑ Stoyanov, E. S.; Kim, K. C.; Reed, C. A. (2006). "The Nature of the H

3O+

Hydronium Ion in Benzene and Chlorinated Hydrocarbon Solvents. Conditions of Existence and Reinterpretation of Infrared Data". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 128 (6): 1948–58. doi:10.1021/ja0551335. PMID 16464096. - ↑ Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 0-08-037941-9.

- ↑ Faure, A.; Tennyson, J. (2003). "Rate coefficients for electron-impact rotational excitation of H+

3 and H

3O+

". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 340 (2): 468–472. Bibcode:2003MNRAS.340..468F. doi:10.1046/j.1365-8711.2003.06306.x. - 1 2 Hollis, J. M.; Churchwell, E. B.; Herbst, E.; De Lucia, F. C. (1986). "An interstellar line coincident with the P(2,l) transition of hydronium (H

3O+

)". Nature. 322 (6079): 524–526. Bibcode:1986Natur.322..524H. doi:10.1038/322524a0. - 1 2 Rauer, H (1997). "Ion composition and solar wind interaction: Observations of comet C/1995 O1 (Hale-Bopp)". Earth, Moon, and Planets. 79: 161–178. Bibcode:1997EM&P...79..161R. doi:10.1023/A:1006285300913.

- ↑ Vejby‐Christensen, L.; Andersen, L. H.; Heber, O.; Kella, D.; Pedersen, H. B.; Schmidt, H. T.; Zajfman, D. (1997). "Complete Branching Ratios for the Dissociative Recombination of H

2O+

, H

3O+

, and CH+

3". The Astrophysical Journal. 483: 531–540. Bibcode:1997ApJ...483..531V. doi:10.1086/304242. - 1 2 Neau, A.; Al Khalili, A.; Rosén, S.; Le Padellec, A.; Derkatch, A. M.; Shi, W.; Vikor, L.; Larsson, M.; Semaniak, J.; Thomas, R.; Någård, M. B.; Andersson, K.; Danared, H.; Af Ugglas, M. (2000). "Dissociative recombination of D

3O+

and H

3O+

: Absolute cross sections and branching ratios". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 113 (5): 1762. Bibcode:2000JChPh.113.1762N. doi:10.1063/1.481979. - ↑ Neufeld, D. A.; Lepp, S.; Melnick, G. J. (1995). "Thermal Balance in Dense Molecular Clouds: Radiative Cooling Rates and Emission-Line Luminosities". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 100: 132. Bibcode:1995ApJS..100..132N. doi:10.1086/192211.

- 1 2 3 4 Wootten, A; Boulanger, F; Bogey, M; Combes, F; Encrenaz, P. J.; Gerin, M; Ziurys, L (1986). "A search for interstellar H

3O+

". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 166: L15–8. Bibcode:1986A&A...166L..15W. PMID 11542067. - ↑ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "heavy water".

- ↑ Herbst, E.; Green, S.; Thaddeus, P.; Klemperer, W. (1977). "Indirect observation of unobservable interstellar molecules". Ap. J. 215: 503–510. Bibcode:1977ApJ...215..503H. doi:10.1086/155381.

- 1 2 Phillips, T. G.; Van Dishoeck, E. F.; Keene, J. (1992). "Interstellar H

3O+

and its Relation to the O2 and H2O Abundances". The Astrophysical Journal. 399: 533. Bibcode:1992ApJ...399..533P. doi:10.1086/171945. hdl:1887/2260. - ↑ "H

3O+

formation reactions". The UMIST Database for Astrochemistry. - ↑ Herbst, E.; Klemperer, W. (1973). "The formation and depletion of molecules in dense interstellar clouds". Ap. J. 185: 505. Bibcode:1973ApJ...185..505H. doi:10.1086/152436.

- ↑ Schwarz, H.A. (1977). "Gas phase infrared spectra of oxonium hydrate ions from 2 to 5 μm". J. Chem. Phys. 67 (12): 5525. Bibcode:1977JChPh..67.5525S. doi:10.1063/1.434748.

- ↑ Wootten, A.; Turner, B. E.; Mangum, J. G.; Bogey, M.; Boulanger, F.; Combes, F.; Encrenaz, P. J.; Gerin, M. (1991). "Detection of interstellar H3O+ – A confirming line". The Astrophysical Journal. 380: L79. Bibcode:1991ApJ...380L..79W. doi:10.1086/186178.

- ↑ Timmermann, R.; Nikola, T.; Poglitsch, A.; Geis, N.; Stacey, G. J.; Townes, C. H. (1996). "Possible discovery of the 70 µm {H3O+} 4−

3 − 3+

3 transition in Orion BN-IRc2". The Astrophysical Journal. 463 (2): L109. Bibcode:1996ApJ...463L.109T. doi:10.1086/310055. - ↑ Goicoechea, J. R.; Cernicharo, J. (2001). "Far-infrared detection of H3O+ in Sagittarius B2". The Astrophysical Journal. 554 (2): L213. Bibcode:2001ApJ...554L.213G. doi:10.1086/321712.