Hypnerotomachia Poliphili

Poliphilo kneels before Queen Eleuterylida | |

| Author | Francesco Colonna |

|---|---|

| Original title | Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, ubi humana omnia non nisi somnium esse docet. Atque obiter plurima scitu sane quam digna commemorat. |

| Translator | Joscelyn Godwin |

| Country | Italy |

| Language | Italian / Latin |

| Genre | Romance, allegorical fantasy |

| Publisher | Aldus Manutius |

Publication date | 1499 |

Published in English | 1999 |

| Media type | Print (hardcover) |

Hypnerotomachia Poliphili(/hiːpˌnɛəroʊtəˈmɑːkiːə pəˈliːfəˌliː/; from Greek hýpnos, 'sleep', éros, 'love', and máchē, 'fight'), called in English Poliphilo's Strife of Love in a Dream or The Dream of Poliphilus, is a romance said to be by Francesco Colonna and a famous example of early printing. First published in Venice in 1499, in an elegant page layout, with refined woodcut illustrations in an Early Renaissance style, Hypnerotomachia Poliphili presents a mysterious arcane allegory in which Poliphilo pursues his love Polia through a dreamlike landscape, and is, seemingly, at last reconciled with her by the Fountain of Venus.

History

The book was printed by Aldus Manutius in Venice in December 1499. The book is anonymous, but an acrostic formed by the first, elaborately decorated letter in each chapter in the original Italian reads POLIAM FRATER FRANCISCVS COLVMNA PERAMAVIT, "Brother Francesco Colonna has dearly loved Polia." Despite this, scholars have also attributed the book to Leon Battista Alberti, and earlier, to Lorenzo de Medici. The latest contribution in this respect was the attribution to Aldus Manutius, and a different Francesco Colonna, this one a wealthy Roman Governor. The author of the illustrations is even less certain.

The subject matter lies within the tradition of the genre of Romance within the conventions of courtly love, which still provided engaging thematic matter for Quattrocento aristocrats. The Hypnerotomachia also draws from a humanist tradition of arcane writings as a demonstration of classical thought.

The text of the book is written in a bizarre Latinate Italian, full of words based on Latin and Greek roots without explanation. The book, however, also includes words from the Italian language, as well as illustrations including Arabic and Hebrew words; Colonna also invented new languages when the ones available to him were inaccurate. (It also contains some uses of Egyptian hieroglyphs, but they are not authentic, most being drawn from a medieval text called Hieroglyphica of dubious origin.) Its story, which is set in 1467, consists of precious and elaborate descriptions of scenes involving the title character, Poliphilo ("Friend of Many Things", from Greek Polloi "Many" + Philos "Friend"), as he wanders a sort of bucolic-classical dreamland in search of his love Polia ("Many Things"). The author's style is elaborately descriptive and unsparing in its use of superlatives. The text makes frequent references to classical geography and mythology, mostly by way of comparison.

The book has long been sought after as one of the most beautiful incunabula ever printed.[1] The typography is famous for its quality and clarity, in a roman typeface cut by Francesco Griffo, a revised version of a type which Aldus had first used in 1496 for the De Aetna of Pietro Bembo. The type was revived by the Monotype Corporation in 1923 as Poliphilus.[2] Another revival, of the earlier version of Griffo's type, was completed under the direction of Stanley Morison in 1929 as Bembo. The type is thought to be one of the first examples of the italic typeface, and unique to the Aldine Press in incunabula.

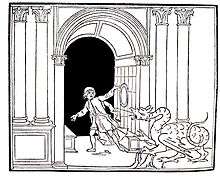

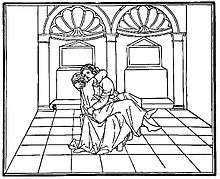

The book is illustrated with 168 exquisite woodcuts showing the scenery, architectural settings, and some of the characters Poliphilo encounters in his dreams. They depict scenes from Poliphilo's adventures, or the architectural features over which the text rhapsodizes, in a simultaneously stark and ornate line art style which perfectly integrates with the type. These images are also interesting because they shed light on what people in the Renaissance fancied about the alleged æsthetic qualities of Greek and Roman antiquities. In the United States, a book on the life and works of Aldus Manutius by Helen Barolini was set within pages that reproduce all the illustrations and many of the full pages from the original work, reconstructing the original layout.[3]

The psychologist Carl Jung admired the book, believing the dream images presaged his theory of archetypes. The style of the woodcut illustrations had a great influence on late-nineteenth-century English illustrators, such as Aubrey Beardsley, Walter Crane, and Robert Anning Bell.

Hypnerotomachia Poliphili was partially translated into English in a London edition of 1592 by "R. D.", believed to be Robert Dallington, who gave it the title by which it is best known in English, The Strife of Love in a Dream.[4] The first complete English version was published in 1999, five hundred years after the original, translated by musicologist Joscelyn Godwin.[5] However the translation uses standard, modern language, rather than following the original's pattern of coining and borrowing words.

Since the 500th anniversary in 1999 also several other modern translations have been published: into modern Italian as part of the great (vol. 1: fac-simile; vol. 2: translation, introductory essays and more than 700 pages of commentary) edition by Marco Ariani and Mino Gabriele;[6] into Spanish by Pilar Pedraza Martinez;[7] into Dutch with one volume of commentary by Ike Cialona;[8] into German, the commentary inserted into the text, by Thomas Reiser.[9]

A complete Russian translation by art historian Boris Sokolov is now in progress, of which the "Cythera Island" part was published in 2005 and is available online. The book is planned as a precise reconstruction of the original layout, with Cyrillic types and typography by Sergei Egorov.

Ten of the monuments described in the Hypnerotomachia were reconstructed by computer graphics and were first published by Esteban A. Cruz in 2006,[10] and in 2012.[11] In 2007, he established a full, design-study project Formas Imaginisque Poliphili, an ongoing independent research project with the objective of reconstructing the content of the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, through a multi-disciplinary approach, and with the aid of virtual and traditional reconstruction technology and methods.

Plot summary

The book begins with Poliphilo, who has spent a restless night because his beloved, Polia, shunned him. Poliphilo is transported into a wild forest, where he gets lost, encounters dragons, wolves and maidens and a large variety of architecture, escapes, and falls asleep once more.

He then awakens in a second dream, dreamed within the first. In the dream, he is taken by some nymphs to meet their queen, and there he is asked to declare his love for Polia, which he does. He is then directed by two nymphs to three gates. He chooses the third, and there he discovers his beloved. They are taken by some more nymphs to a temple to be engaged. Along the way they come across five triumphal processions celebrating the union of the lovers. Then they are taken to the island of Cythera by barge, with Cupid as the boatswain; there they see another triumphal procession celebrating their union. The narrative is interrupted, and a second voice takes over, as Polia describes his erotomania from her own point of view.

Poliphilo resumes his narrative after one-fifth of the book. Polia rejects Poliphilo, but Cupid appears to her in a vision and compels her to return and kiss Poliphilo, who has fallen into a deathlike swoon at her feet, back to life. Venus blesses their love, and the lovers are united at last. As Poliphilo is about to take Polia into his arms, Polia vanishes into thin air and Poliphilo wakes up.

Characters

- Poliphilus

- Polia

Gallery

Allusions/references in other works

- The book is briefly mentioned in The Histories of Gargantua and Pantagruel (1532–34) by François Rabelais: "Far otherwise did heretofore the sages of Egypt, when they wrote by letters, which they called hieroglyphics, which none understood who were not skilled in the virtue, property, and nature of the things represented by them. Of which Orus Apollon hath in Greek composed two books, and Polyphilus, in his Dream of Love, set down more..." (Book 1, Ch. 9.)

- In the preface to her first novel, Ibrahim ou l'illustre bassa (1641), Madeleine de Scudéry advises novelists to avoid ornate descriptions like "Poliphile in his dreams, who hath set down most strange terms" (1652 English translation).

- Hypnerotomachia Poliphili: Re-Discovering Antiquity Through The Dreams Of Poliphilus (2007) by Esteban Alejandro Cruz features more than 50 original colour reconstructions of the architecture and topiary gardens of eight monuments described in the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili: A Great Pyramid, A Great Hippodromus, An Elephant bearing an Obelisk, A Monument to the Un-Happy Horse, the Grand Arch, The Palace and Gardens of Queen Eleutirillide (Liberty), The Temple to Venus Physizoa, and the Polyandrion (Cemetery of Lost Loves).

- Hypnerotomachia Poliphili: An Architectural Vision from the First Renaisssance" (2012) by Esteban Alejandro Cruz, with more than 160 colour reconstructions, revising the previous monuments from his first book, and adding a few others: The Bath of the Five Nymphs, a Majestic Bridge, a Fountain dedicated to the Mother of all Things, An Ancient Port, the Displuvium Garden and its "Curious" Obelisk.

- Polyphilo: or The Dark Forest Revisited - An Erotic Epiphany of Architecture (1992) is a modern re-writing of Polyphilo's tale by Alberto Pérez-Gómez. The non-fictional preface to this book by this eminent architectural historian is an excellent introduction to the Hypnerotomachia.

- Gypnerotomahiya (Гипнэротомахия, 1992) is an 8-minute Russian animation directed by Andrey Svislotskiy of Pilot Animation Studio made based on the novel of the same title.

- The 1993 novel The Club Dumas by Arturo Pérez-Reverte mentions the 1545 edition of the Hypnerotomachia (Ch. 3). The book is again mentioned in Polanski's 1999 film, The Ninth Gate, based loosely on Pérez-Reverte's novel (this time, by its Italian title, "La Hypnerotomachia di Poliphilo").

- The title and many themes of John Crowley's 1994 novel Love & Sleep (part of his Ægypt series) were derived from the Hypnerotomachia.

- Geerten Meijsing's 2000 novel Dood meisje refers in many ways to the Hypnerotomachia.

- In the 2004 novel The Rule of Four by Ian Caldwell and Dustin Thomason, two students try to decode the mysteries of Hypnerotomachia Poliphili.[12]

- Umberto Eco's 2004 novel The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana features a protagonist whose doctoral thesis was written on the Hypnerotomachia.

Notes

- ↑ Schuessler, Jennifer (23 July 2012). "Rare Book School at the University of Virginia". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- ↑ Poliphilus Font Family by Monotype Design Studio.

- ↑ Barolini, Helen. Aldus and His Dream Book: An Illustrated Essay. New York: Italica Press, 1992.

- ↑ Robert Dallington [presumed] (1592), The Strife of Love in a Dream. In 1890 a limited (500 copies) edition of the first book was published by David Nutt in the Strand. This was edited by Andrew Laing. Online version at the Internet Archive, accessed on 2010-02-08.

- ↑ Joscelyn Godwin (transl.) (1999), Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, the Strife of Love in a Dream, a modern English translation, set in the Poliphilus typeface. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-01942-8. Paperback edition published in 2005.

- ↑ Marco Ariani, Mino Gabriel (edd., transl., comm.) (1998sqq.), Francesco Colonna: Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, Milan: Adelphi (Classici 66) ISBN 978-8-845-91424-9. Paperback edition ISBN 978-8-845-91941-1.

- ↑ Pilar Pedraza Martinez (transl.) (1999), Francesco Colonna: Sueño de Polífilo, Barcelona: El Acantilado 17, ISBN 978-8-495-35905-6.

- ↑ Ike Cialona (transl., comm.) (2006), Francesco Colonna: De droom van Poliphilus (Hypnerotomachia Poliphili), Amsterdam: Athenaeum – Polak & Van Gennep, ISBN 978-9-025-30668-7.

- ↑ Thomas Reiser (transl., comm.) (2014), Francesco Colonna: Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, Interlinearkommentarfassung, Breitenbrunn: Theon Lykos 1a, ISBN 978-1-499-20611-1.

- ↑ Esteban Alejandro Cruz (2007), Hypnerotomachia Poliphili: Re-Discovering Antiquity Through The Dreams Of Poliphilus

- ↑ Esteban Alejandro Cruz (2012), "Hypnerotomachia Poliphili: An Architectural Vision from the First Renaissance"

- ↑ Joscelyn Godwin (2004), The Real Rule of Four: The Unauthorized Guide to The New York Times Bestseller. ISBN 1-932857-08-7.

References

- Blunt, Anthony, "The Hypnerotomachia Poliphili in Seventeenth Century France", Journal of Warburg and Courtauld, October 1937

- Fiertz-David, Linda. The Dream of Poliphilo: The Soul in Love, Spring Publications, Dallas, 1987 (Bollingen Lectures).

- Gombrich, E.H., Symbolic Images, Phaidon, Oxford, 1975, "Hypnerotomachiana".

- Lefaivre, Liane. Leon Battista Alberti's Hypnerotomachia Poliphili: Re-cognizing the architectural body in the early Italian Renaissance. Cambridge, Mass. [u.a.]: MIT Press 1997. ISBN 0-262-12204-9.

- Pérez-Gómez, Alberto. Polyphilo or The Dark Forest Revisited: An Erotic Epiphany of Architecture. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press 1992. ISBN 0-262-16129-X, Introduction by Alberto Pérez-Gómez.

- Schmeiser, Leonhard. Das Werk des Druckers. Untersuchungen zum Buch Hypnerotomachia Poliphili. Maria Enzersdorf: Edition Roesner 2003. ISBN 3-902300-10-8, Austrian philosopher argues for Aldus Manutius' authorship.

- Tufte, Edward. Chapter in Beautiful Evidence

- Cruz, Esteban Alejandro, Hypnerotomachia Poliphili: Re-discovering Antiquity Through the Dreams of Poliphilus Victoria: Trafford Publishing, 2006. ISBN 1-4120-5324-2. Artist reconstructions of the architecture and landscapes described by Poliphilus during his amorous quest through Antiquity.

- Cruz, Esteban Alejandro, "Hypnerotomachia Poliphili: An Architectural Vision from the First Renaissance" London: Xlibris Publishing, 2012. VOL 1: 978-1-4628-7247-3, VOL 2: 978-1-4771-0069-1. A second book of what seems to become a series of publications on the subject.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hypnerotomachia Poliphili. |

The original 1499 edition

- Hypnerotomachia Poliphili : ubi humana omnia non nisisomnium esse docet atque obiter plurima scitu sane quam digna commemorat: digital version, from the Boston Public Library collection at Archive.org

- The Electronic Hypnerotomachia: facsimile and discussion, from the MIT Press

- high-resolution photographs From the Rare Book and Special Collections Division at the Library of Congress

- Complete digital surrogate: of copy in the Menil Collection Library in Houston Texas.

- high-resolution scan of a copy in the Herzog August Bibliothek Wolfenbüttel

- In PDF, TXT (ZIP), and RTF (ZIP) formats from Liber Liber

- Facsimile of thirteen pages, with a five-minute reading from Godwin's 1999 translation (from the State Library of Victoria)

- van der Lee, Peter. Hypnerotomachia Poliphili. vimeo.com.

The 1592 English edition

- Hypnerotomachia at Project Gutenberg

- The Strife of Love in a Dreame In PDF or DJVU, and beta flip-book formats

The French editions

- Les Livres D’Architecture at Architectura

- Woodcuts from the French edition with iconographic descriptions in the Warburg Institute Iconographic Database

The Russian edition

Background and interpretation

- Book of the Month article from the Glasgow University Library's Special Collections Department

- Prints & People: A Social History of Printed Pictures, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (see index)

Research Projects

- Formas Imaginisque Poliphili: Imaginary models of Poliphilus revealed. Reconstruction of the architecture, gardens, landscapes, monuments, interiors, accessories, and objects as described in the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili though a multi-disciplinary research platform, and with the aid of virtual applications and methods used in the Cultural Heritage Industry.