In a Station of the Metro

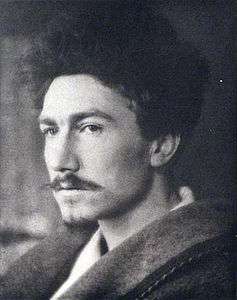

"In A Station of the Metro" is an Imagist poem by Ezra Pound published in 1913 in the literary magazine Poetry.[1] In the poem, Pound describes a moment in the underground metro station in Paris in 1912; Pound suggested that the faces of the individuals in the metro were best put into a poem not with a description but with an "equation". Because of the treatment of the subject's appearance by way of the poem's own visuality, it is considered a quintessential Imagist text.[2]

The poem was reprinted in Pound's collection Lustra in 1917, and again in the 1926 anthology Personae: The Collected Poems of Ezra Pound, which compiled his early pre-Hugh Selwyn Mauberley works.

The poem

The apparition of these faces in the crowd;

Petals on a wet, black bough.

The poem contains only fourteen words (without a verb therein, a good example of the Verbless Poetry form).[3]

Pound was influential in the creation of Imagist poetry until he left the movement to embrace Vorticism in 1914. Pound, though briefly, embraced Imagism stating that it was an important step away from the verbose style of Victorian literature and suggested that it "is the sort of American stuff I can show here in Paris without its being ridiculed".[4] "In a Station of the Metro" is an early work of Modernist poetry as it attempts to "break from the pentameter", incorporates the use of visual spacing as a poetic device, and does not contain any verbs. [2]

Analysis

The poem was first published in 1913 and is considered one of the leading poems of the Imagist tradition. Pound's process of deletion from thirty lines[5] to only fourteen words typifies Imagism's focus on economy of language, precision of imagery and experimenting with non-traditional verse forms. The poem is Pound’s written equivalent for the moment of revelation and intense emotion he felt at the Metro at La Concorde, Paris.

The poem is essentially a set of images that have unexpected likeness and convey the rare emotion that Pound was experiencing at that time. Arguably the heart of the poem is not the first line, nor the second, but the mental process that links the two together. "In a poem of this sort," as Pound explained, "one is trying to record the precise instant when a thing outward and objective transforms itself, or darts into a thing inward and subjective."

By linking human faces, a synecdoche for people themselves, with petals on a damp bough, the poet calls attention to both the elegance and beauty of human life, as well as its transience. A dark, wet bough implies that it has just rained, and the petals stuck to the bough were shortly before attached to flowers from the tree. They may still be living, but they will not be for long. In this way, Pound calls attention to human mortality as a whole - we are all dying.

The word "apparition" is considered crucial as it implies both presence and absence – and thus transience as mentioned previously. It gives human life a spiritual, mystical significance, but one that we can never be sure of.

The plosive word "Petals" conjures ideas of delicate, feminine beauty which contrasts with the bleakness of the "wet, black bough". What the poem signifies is questionable; many critics argue that it deliberately transcends traditional form and therefore its meaning is solely found in its technique as opposed to in its content. Additionally, some have interpreted the poem to be a Memento Mori. However when Pound had the inspiration to write this poem few of these considerations came into view. He simply wished to translate his perception of beauty in the midst of ugliness into a single, perfect image in written form. It is also worth noting that the number of words in the poem (fourteen) is the same as the number of lines in a sonnet. The words are distributed with eight in the first line and six in the second, mirroring the octet-sestet form of the Italian (or Petrarchan) sonnet.

Woman Admiring Plum Blossoms at Night, Suzuki Harunobu, 18th century

Like other modernist artists of the period, Pound found inspiration in Japanese art, but the tendency was to re-make and to meld cultural styles rather than to copy directly or slavishly. He may have been inspired by a Suzuki Harunobu print he almost certainly saw in the British Library (Richard Aldington mentions the specific prints he matched to verse), and probably attempted to write haiku-like verse during this period.[6]

References

- ↑ Axelrod, Steven Gould and Camille Roman, Thomas J. Travisano.The New Anthology of American Poetry: Traditions and Revolutions, Beginnings to 1900.Rutgers University Press (2003) p.663

- 1 2 Barbarese, J.T. "Ezra Pound's Imagist Aesthetics: Lustra to Mauberley" The Columbia history of American poetryColumbia University Press (1993) pp.307-308

- ↑ Hirsch, Edward 'A Poet's Glossary' Houghton Mifflin, 2014

- ↑ Ayers, David. Modernsim: A Short Introduction. Blackwell (2004) p.2

- ↑ http://www.english.illinois.edu/maps/poets/m_r/pound/metro.htm

- ↑ Video of a lecture discussing the importance of Japanese culture to Pound's early poetry, London University School of Advanced Study, March 2012.

See also

Sources

- Ezra Pound "Vorticism", in The Fortnightly Review, Sept. 1, 1914

- The Cat Empire, "The Crowd", Nov/Dec, 2004

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |