Indirect DNA damage

Indirect DNA damage occurs when a UV-photon is absorbed in the human skin by a chromophore that does not have the ability to convert the energy into harmless heat very quickly.[2] Molecules that do not have this ability have a long-lived excited state. This long lifetime leads to a high probability for reactions with other molecules - so-called bimolecular reactions.[2] Melanin and DNA have extremely short excited state lifetimes in the range of a few femtoseconds (10−15s).[3] The excited state lifetime of these substances is 1,000 to 1,000,000 times longer than the lifetime of melanin,[2] and therefore they may cause damage to living cells that come in contact with them.[4][5][6][7]

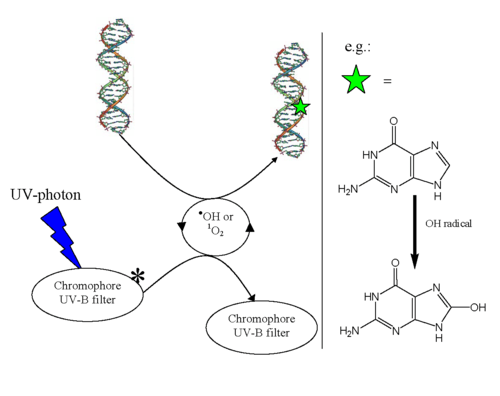

The molecule that originally absorbs the UV-photon is called a "chromophore". Bimolecular reactions can occur either between the excited chromophore and DNA or between the excited chromophore and another species, to produce free radicals and Reactive Oxygen Species. These reactive chemical species can reach DNA by diffusion and the bimolecular reaction damages the DNA (oxidative stress). It is important to note that indirect DNA damage does not result in any warning signal or pain in the human body.

The bimolecular reactions that cause the indirect DNA damage are illustrated in the figure:

1O2 is reactive harmful singlet oxygen:

Location of the damage

Unlike direct DNA damage, which occurs in areas directly exposed to UV-B light, free radicals can travel through the body and affect other areas - possibly even inner organs. The traveling nature of the indirect DNA damage can be seen in the fact that the malignant melanoma can occur in places that are not directly illuminated by the sun—in contrast to basal-cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma, which appear only on directly illuminated locations on the body.

See also

References

- 1 2 singlet oxygen induced DNA damage

- 1 2 3 Cantrell, Ann; McGarvey, David J (2001). "3(Sun Protection in Man)". Comprehensive Series in Photosciences. 495: 497–519. CAN 137:43484.

- ↑ "Ultrafast internal conversion of DNA". Retrieved 2008-02-13.

- ↑ Armeni, Tatiana; Damiani, Elisabetta; et al. (2004). "Lack of in vitro protection by a common sunscreen ingredient on UVA-induced cytotoxicity in keratinocytes.". Toxicology. 203 (1–3): 165–178. doi:10.1016/j.tox.2004.06.008. PMID 15363592.

- ↑ Knowland, John; McKenzie, Edward A.; McHugh, Peter J.; Cridland, Nigel A. (1993). "Sunlight-induced mutagenicity of a common sunscreen ingredient". FEBS Letters. 324 (3): 309–313. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(93)80141-G. PMID 8405372.

- ↑ Mosley, C N; Wang, L; Gilley, S; Wang, S; Yu,H (2007). "Light-Induced Cytotoxicity and Genotoxicity of a Sunscreen Agent, 2-Phenylbenzimidazol in Salmonella typhimurium TA 102 and HaCaT Keratinocytes". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 4 (2): 126–131. doi:10.3390/ijerph2007040006. PMID 17617675.

- ↑ Xu, C.; Green, Adele; Parisi, Alfio; Parsons, Peter G (2001). "Photosensitization of the Sunscreen Octyl p-Dimethylaminobenzoate b UVA in Human Melanocytes but not in Keratinocytes". Photochemistry and Photobiology. 73 (6): 600–604. doi:10.1562/0031-8655(2001)073<0600:POTSOP>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0031-8655. PMID 11421064.