Interpreter of Maladies

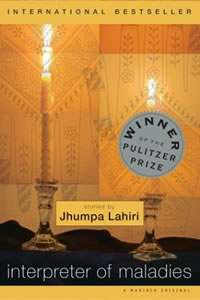

Cover of paperback edition | |

| Author | Jhumpa Lahiri |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Short stories |

| Publisher | Houghton Mifflin |

Publication date | 1999 |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) Ebook |

| Pages | 198 pp |

| ISBN | 0-618-10136-5 |

| OCLC | 40331288 |

| Preceded by | The Namesake |

Interpreter of Maladies is a book collection of nine short stories by Indian American author Jhumpa Lahiri published in 1999. It won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction and the Hemingway Foundation/PEN Award in the year 2000 and has sold over 15 million copies worldwide. It was also chosen as The New Yorker's Best Debut of the Year and is on Oprah Winfrey's Top Ten Book List.

The stories are about the lives of Indians and Indian Americans who are caught between their roots and the "New World."

The Stories

- "A Temporary Matter"

- "When Mr. Pirzada Came to Dine"

- "Interpreter of Maladies"

- "A Real Durwan"

- "Sexy"

- "Mrs. Sen's"

- "This Blessed House"

- "The Treatment of Bibi Haldar"

- "The Third and Final Continent"

Story summaries

A Temporary Matter

A married couple, Shukumar and Shoba, live as strangers in their house until an electrical outage brings them together when all of sudden "they [are] able to talk to each other again" in the four nights of darkness. From the point of view of Shukumar, we are given bits and pieces of memory which slowly gives insight into what has caused the distance in the marriage. For a brief moment, it seems the distance is nothing but perhaps a result of a disagreement. However, descriptions of Shukumar and Shoba’s changed physical appearances begin to hint at something much more than a lovers’ quarrel. We soon find out that both characters’ worn outward appearance results from their internal, emotional strife that has caused such deeply woven alienation from each other.

The husband and wife mourn for their stillborn baby. This traumatic loss casts a tone of melancholia for the rest of the story. However, there is some hope for the couple to reconnect as during each night of blackness, they confess more and more to each other—the things that were never uttered as man and wife. A late night drink with a friend, a ripped out photo from a magazine, and anguish over a sweater vest are all confessions made in the nightly blackouts. Shukumar and Shoba become closer as the secrets combine into a knowledge that seems like the remedy to mend the enormous loss they share together. On the fourth night, we are given the most hope at their reconnection when they "mak[e] love with a desperation they had forgotten."

But just as to be stillborn is to have never begun life, so too does the couple’s effort to rekindle their marriage fail at inception. One last confession is given first by Shoba, then another by Shukumar at the end of "A Temporary Matter". In full confidence with one another, they acknowledge the finality in the loss of their marriage. And finally, "They we[ep] for the things they now knew."

Interpreter of Maladies

Mr. and Mrs. Das, Indian Americans visiting the country of their heritage, hire middle-aged tour guide Mr. Kapasi as their driver for the day as they tour. Mr. Kapasi notes the parents’ immaturity. Mr. and Mrs. Das look and act young to the point of childishness, go by their first names when talking to their children, Ronny, Bobby, and Tina, and seem selfishly indifferent to the kids. On their trip, when her husband and children get out of the car to sightsee, Mrs. Das sits in the car, eating snacks she offers to no one else, wearing her sunglasses as a barrier, and painting her nails. When Tina asks her to paint her nails as well, Mrs. Das just turns away and rebuffs her daughter.

Mr. and Mrs. Das ask the good-natured Mr. Kapasi about his job as a tour guide, and he tells them about his weekday job as an interpreter in a doctor’s office. Mr. Kapasi’s wife resents her husband’s job because he works at the doctor’s clinic that previously failed to cure their son of typhoid fever. She belittles his job, and he, too, discounts the importance of his occupation as a waste of his linguistic skills. However, Mrs. Das deems it “romantic” and a big responsibility, pointing out that the health of the patients depends upon Mr. Kapasi’s correct interpretation of their maladies.

Mr. Kapasi begins to develop a romantic interest in Mrs. Das, and conducts a private conversation with her during the trip. Mr. Kapasi imagines a future correspondence with Mrs. Das, picturing them building a relationship to translate the transcontinental gap between them. However, Mrs. Das reveals a secret: she tells Mr. Kapasi the story of an affair she once had, and that her son Bobby had been born out of her adultery. She explains that she chose to tell Mr. Kapasi because of his profession; she hopes he can interpret her feelings and make her feel better as he does for his patients, translating without passing judgment. However, when Mr. Kapasi reveals his disappointment in her and points out her guilt, Mrs. Das storms off.

As Mrs. Das walks away towards her family, she leaves a trail of crumbs of puffed rice snacks, and monkeys begin to trail her. The neglectful Das parents don’t notice as the monkeys, following Mrs. Das’s food trail, surround their son, Bobby, isolating the son born of a different father. The monkeys begin to attack Bobby, and Mr. Kapasi rushes in to save him. Mr. Kapasi returns Bobby to his parents, and looks on as they clean up their son.

A Real Durwan

Boori Ma is a feeble 64-year-old woman from Calcutta who is the stairsweeper, or durwan, of an old brick building. In exchange for her services, the residents allow Boori Ma to sleep in front of the collapsible gates leading into the tenement. While sweeping, she narrates stories of her past: her daughter’s extravagant wedding, her servants, her estate and her riches. The residents of the brick building hear continuous contradictions in Boori’s storytelling, but her stories are seductive and compelling, so they let her contradictions rest. One family in particular takes a liking to Boori Ma, the Dalals. Mrs. Dalal often gives Boori Ma food and takes care of her ailments. When Mr. Dalal gets promoted at work, he improves the brick building by installing a sink in the stairwell and a sink in his home. The Dalals continue to improve their home and even go away on a trip to Simla for ten days and promise to bring Boori Ma a sheep’s hair blanket. While the Dalals are away, the other residents become obsessed with making their own improvement to the building. Boori Ma even spends her life savings on special treats while circling around the neighborhood. However, while Boori Ma is out one afternoon, the sink in the stairwell is stolen. The residents accuse Boori Ma of informing the robbers and in negligence for her job. When Boori Ma protests, the residents continue to accuse her because of all her previous inconsistent stories. The residents' obsession with materializing the building dimmed their focus on the remaining members of their community, like Boori Ma. The short story concludes as the residents throw out Boori Ma’s belongings and begin a search for a 'real durwan'. Note that 'durwan' means housekeeper in both Bengali and Hindi.

Sexy

“Sexy” centers on Miranda, a young white woman who has an affair with a married Indian man named Dev. Although one of Miranda's work friends is an Indian woman named Laxmi, Miranda knows very little about India and its culture. The first time she meets Dev, she is not able to discern his ethnicity. However, she is instantly captivated by his charm and the thrill of being with an exotic, older man. Dev takes Miranda to the Mapparium, where he whispers "You are sexy." Miranda buys "sexy" clothes that she thinks are suitable for a mistress, but feels pangs of guilt because Dev is married. Meanwhile, Laxmi’s cousin has been abandoned by her husband, who left the cousin for a younger woman. One day, Laxmi’s cousin comes to Boston and Miranda is asked to babysit the cousin's seven-year-old son, Rohin. Rohin asks Miranda to try on the sexy clothes that she bought, and gives Miranda insight into his mother’s grief. Miranda decides that she and Dev's wife both "deserve better," and stops seeing Dev.

Mrs. Sen's

In this story, 11-year-old Eliot begins staying with Mrs. Sen—a university professor's wife—after school. The caretaker, Mrs. Sen, chops and prepares food as she tells Elliot stories of her past life in Calcutta, helping to craft her identity. Like "A Temporary Matter," this story is filled with lists of produce, catalogs of ingredients, and descriptions of recipes. Emphasis is placed on ingredients and the act of preparation. Other objects are emphasized as well, such as Mrs. Sen's colorful collection of saris from her native India. Much of the plot revolves around Mrs. Sen's tradition of purchasing fish from a local seafood market. This fish reminds Mrs. Sen of her home and holds great significance for her. However, reaching the seafood market requires driving, a skill that Mrs. Sen has not learned and resists learning. At the end of the story, Mrs. Sen attempts to drive to the market without her husband, and ends up in an automobile accident. Eliot soon stops staying with Mrs. Sen thereafter.

This Blessed House

Sanjeev and Twinkle, a newly married couple, are exploring their new house in Hartford, which appears to have been owned by fervent Christians: they keep finding gaudy Biblical paraphernalia hidden throughout the house. While Twinkle is delighted by these objects and wants to display them everywhere, Sanjeev is uncomfortable with them and reminds her that they are Hindu, not Christian. This argument reveals other problems in their relationship; Sanjeev doesn’t seem to understand Twinkle’s spontaneity, whereas Twinkle has little regard for Sanjeev’s discomfort. He is planning a party for his coworkers and is worried about the impression they might get from the interior decorating if their mantelpiece is full of Biblical figurines. After some arguing and a brief amount of tears, a compromise is reached. When the day of the party arrives, the guests are enamored with Twinkle. Sanjeev still has conflicting feelings about her; he is captivated by her beauty and energy, but irritated by her naivete and impractical tendencies. The story ends with her and the other party guests discovering a large bust of Jesus Christ in the attic. Although the object disgusts him, he obediently carries it downstairs. This action can either be interpreted as Sanjeev giving into Twinkle and accepting her eccentricities, or as a final, grudging act of compliance in a marriage that he is reconsidering.

The Treatment of Bibi Haldar

29-year-old Bibi Haldar is gripped by a mysterious ailment, and myriad tests and treatments have failed to cure her. She has been told to stand on her head, shun garlic, drink egg yolks in milk, to gain weight and to lose weight. The fits that could strike at any moment keep her confined to the home of her dismissive elder cousin and his wife, who provide her only meals, a room, and a length of cotton to replenish her wardrobe each year. Bibi keeps the inventory of her brother's cosmetics stall and is watched over by the women of their community. She sweeps the store, wondering loudly why she was cursed to this fate, to be alone and jealous of the wives and mothers around her. The women come to the conclusion that she wants a man. When they show her artifacts from their weddings, Bibi proclaims what her own wedding will look like. Bibi is inconsolable at the prospect of never getting married. The women try to calm her by wrapping her in shawls, washing her face or buying her new blouses. After a particularly violent fit, her cousin Haldar emerges to take her to the polyclinic. A remedy is prescribed—marriage: “Relations will calm her blood.” Bibi is delighted by this news and begins to plan and plot the wedding and to prepare herself physically and mentally. But Haldar and his wife dismiss this possibility. She is nearly 30, the wife says, and unskilled in the ways of being a woman: her studies ceased prematurely, she is not allowed to watch TV, she has not been told how to pin a sari or how to prepare meals. The women don’t understand why, then, this reluctance to marry her off if she such a burden to Haldar and his wife. The wife asks who will pay for the wedding?

One morning, wearing a donated sari, Bibi demands that Haldar take her to be photographed so her image can be circulated among the bachelors, like other brides-in-waiting. Haldar refuses. He says she is a bane for business, a liability and a loss. In retaliation, Bibi stops calculating the inventory for the shop and circulates gossip about Haldar’s wife. To quiet her down, Haldar places an ad in the paper proclaiming the availability of an “unstable” bride. No family would take the risk. Still, the women try to prepare her for her wifely duties. After two months of no suitors, Haldar and his wife feel vindicated. Things were not so bad when Bibi’s father was alive. He created charts of her fits and wrote to doctors abroad to try to cure her. He also distributed information to the members of the village so they were aware of her condition. But now only the women can look after her while being thankful, in private, that she is not their responsibility.

When Haldar’s wife gets pregnant, Bibi is kept away from her for fear of infecting the child. Her plates are not washed with the others, and she is given separate towels and soap. Bibi suffers another attack on the banks of the fish pond, convulsing for nearly two minutes. The husbands of the village escort her home in order to find her rest, a compress, and a sedative tablet. But Haldar and his wife do not let her in. That night, Bibi sleeps in the storage room. After a difficult birth, Haldar’s wife delivers a girl. Bibi sleeps in the basement and is not allowed direct contact with the girl. She suffers more unchecked fits. The women voice their concern but it goes unheeded. They take their business elsewhere and the cosmetics in the stall soon expire on their shelves. In autumn, Haldar’s daughter becomes ill. Bibi is blamed. Bibi moves back into the storeroom and stops socializing—and stops searching for a husband. By the end of the year, Haldar is driven out of business, and he packs his family up and moves away. He leaves Bibi behind with only a thin envelope of cash.

There is no more news of them and a letter written to Bibi’s only other known relative is returned by the postal service. The women spruce up the storeroom and send their children to play on their roof in order to alert others in the event of an attack. At night, however, Bibi is left alone. Haggard, she circles the parapet but never leaves the roof. In spring, vomit is discovered by the cistern and the women find Bibi, pregnant. The women search for traces of assault, but Bibi’s storeroom is tidy. She refuses to tell the women who the father is, only saying that she can’t remember what happened. A ledger with men’s names lay open near her cot. The women help her carry her son to term and teach her how to care for the baby. She takes Haldar’s old creams and wares out of the basement and reopens his shop. The women spread the word and soon the stall is providing enough money for Bibi to raise her boy. For years, the women try to sniff out who had disgraced Bibi but to no avail. The one fact they could agree upon is that Bibi seemed to be cured.

The Third and Final Continent

In "The Third and Final Continent", the narrator lives in India, then moves to London, then finally to America. The title of this story tells us that the narrator has been to three different continents and chooses to stay in the third, North America. As soon as the narrator arrives he decides to stay at the YMCA. After saving some money he decides to move somewhere a little more like home. He responds to an advertisement in the paper and ends up living with an elderly woman. At first he is very respectful and courteous to the elderly woman. The narrator does not feel that he owes the old woman anything and does not really go out of his way for her.

But after he discovers that the elderly woman is one hundred and three years old he then changes. He becomes more caring and even amazed that this old woman has lived for one hundred and three years. Because of this woman's age she is not accustomed to the modern times in which this story takes place. The narrator just like the elderly woman is not accustomed to the times in America but also America in general. So this may help the narrator to feel more comfortable in his new setting. After living with the elderly woman for about six weeks, the narrator grows somewhat attached to this woman.

Once his wife, who he was set up beforehand to marry, arrives in America he then decides to move to a bigger home. Upon this decision, he also realizes that he is going to have to look out for and nurture his new wife. After living with his wife for some time, who he at first had barely known, he soon finds out that the elderly woman he had once lived with is now dead. This hurts him because this is the first person in America for whom he had felt any feelings. After the woman's death, he then becomes more comfortable with his wife, not because the woman died but because of the time he is spending with his wife. Just like his relationship with elderly woman, the more time he spends with a person the closer he becomes with them. After time the narrator becomes in love with his wife and is constantly remembering the elderly woman with whom he had once lived.

Story analyses

Analysis of "Mrs. Sen's"

Mrs. Sen, the eponymous character of Lahiri’s story demonstrates the power that physical objects have over the human experience. During the entire story, Mrs. Sen is preoccupied with the presence or lack of material objects that she once had. Whether it is fish from her native Calcutta or her special vegetable cutting blade, she clings to the material possessions that she is accustomed to, while firmly rejecting new experiences such as canned fish or even something as mundane as driving a car. While her homesickness is certainly understandable given her lack of meaningful social connections, her item-centric nostalgia only accentuates the fact that the people she meets in America are no barrier to her acclimation. The man at the fish market takes the time to call Mrs. Sen and reserve her special fish. The policeman who questions Mrs. Sen after her automobile accident does not indict her. For all intents and purposes, the people in the story make it easy for Mrs. Sen to embrace life in America. But despite this, Mrs. Sen refuses to assimilate to any degree, continuing to wrap herself in saris, serving Indian canapés to Eliot’s mother, and putting off the prospect of driving. By living her life vicariously through remembered stories imprinted on her blade, her saris, and her grainy aerograms, Mrs. Sen resists assimilation through the power of material objects and the meaning they hold for her.

Analysis of "The Third and Final Continent"

In contrast to depictions of resistance to Indian culture found in several of the stories in Lahiri’s collection, "The Third And Final Continent" portrays a relatively positive story of the Indian-American experience. In this story, the obstacles and hardships that the protagonist must overcome are much more tangible, such as learning to stomach a diet of cornflakes and bananas, or boarding in a cramped YMCA. The protagonist’s human interactions demonstrate a high degree of tolerance and even acceptance of Indian culture on the part of the Americans he meets. Mrs. Croft makes a point of commenting on the protagonist’s sari-wrapped wife, calling her “a perfect lady” (195). Croft’s daughter Helen also remarks that Cambridge is “a very international city,” hinting at the reason why the protagonist is met with a general sense of acceptance. In 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 into law, abolishing several immigration quotas. This piece of legislation resulted in a massive surge of immigration from Asian countries, including India during the late 1960s and 1970s. In particular, this allowed many Asians to come to the US under the qualification of being a “professional, scientist, or artist of exceptional ability” contributing to the reputation of Asian-Americans as being intelligent, mannered, and a model minority. In this story, the only reason the narrator even meets Mrs. Croft is because he is an employee of MIT, a venerable institution of higher learning. Whereas prior to the INS Act of 1965, Asians were often seen as a yellow menace that was only tolerable because of their small numbers (0.5% of the population), by the time the Asian immigration boom tapered off in the 1990s, their reputation as a model minority had been firmly cemented, building a reputation for Asian Americans of remarkable educational and professional success.[1] By ending on a cultural tone of social acceptance and tolerance, Lahiri suggests that the experience of adapting to American society is ultimately achievable.

Critical reception

Overall the book received generally positive reviews. Interpreter of Maladies garnered universal acclaim from myriad publications. Michiko Kakutani of the New York Times praises Lahiri for her writing style, citing her "uncommon elegance and poise." Time applauded the collection for "illuminating the full meaning of brief relationships—with lovers, family friends, those met in travel".[2] Ronny Noor asserts, "The value of these stories—although some of them are loosely constructed—lies into fact that they transcend confined borders of immigrant experience to embrace larger age-old issues that are, in the words of Ralph Waldo Emerson, 'cast into the mould of these new times' redefining America."[3]

Noelle Brada-Williams notes that Indian-American literature is under-represented and that Lahiri deliberately tries to give a diverse view of Indian Americans so as not to brand the group as a whole. She also argues that Interpreter of Maladies is not just a collection of random short stories that have common components, but a "short story cycle" in which the themes and motifs are intentionally connected to produce a cumulative effect on the reader: "...a deeper look reveals the intricate use of pattern and motif to bind the stories together, including recurring themes of the barriers to and opportunities for human communication; community, including marital, extra-marital, and parent-child relationships; and the dichotomy of care and neglect."[4]

Ketu H. Katrak reads The Interpreter of Maladies as reflecting the trauma of self-transformation through immigration, which can result in a series of broken identities that form "multiple anchorages." Lahiri's stories show the diasporic struggle to keep hold of culture as characters create new lives in foreign cultures. Relationships, language, rituals, and religion all help these characters maintain their culture in new surroundings even as they build a "hybrid realization" as Asian Americans.[5]

Laura Anh Williams observes the stories as highlighting the frequently omitted female diasporic subject. Through the foods they eat, and the ways they prepare and eat them, the women in these stories utilize foodways to construct their own unique racialized subjectivity and to engender agency. Williams notes the ability of food in literature to function autobiographically, and in fact, Interpreter of Maladies indeed reflects Lahiri’s own family experiences. Lahiri recalls that for her mother, cooking "was her jurisdiction. It was also her secret." For individuals such as Lahiri's' mother, cooking constructs a sense of identity, interrelationship, and home that is simultaneously communal and yet also highly personal.[6][7]

Translation

Interpreter of Maladies has been translated into many languages:

| Title | Language | Translator | Year | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bedonar Bhashyakar | Bengali | Kamalika Mitra, Payel Sengupta | 2009 | OCLC 701116398 |

| Intèrpret d'emocions | Catalan | Andreu Garriga i Joan | 2000 | OCLC 433389700 |

| 疾病解说者 (Jíbìng Jiěshuōzhě) | Chinese (Mainland China edition) | Wu Bingqing, Lu Xiaohui | 2005 | OCLC 61357011 |

| 醫生的翻譯員 (Yīshēng de Fānyìyuán) | Chinese (Taiwan edition) | Wu Meizhen | 2001 | OCLC 814021559 |

| Een tijdelijk ongemak | Dutch | Marijke Emeis | 1999 | OCLC 67724681 |

| L'interprète des maladies | French | Jean-Pierre Aoustin | 2000 | OCLC 45716386 |

| Melancholie der Ankunft | German | Barbara Heller | 2000 | OCLC 46621568 |

| פרשן המחלות (Parshan ha-maḥalot) | Hebrew | Shelomit Apel | 2001 | OCLC 48419549 |

| Penerjemah luka | Indonesian | Gita Yuliani | 2006 | OCLC 271894107 |

| L'interprete dei malanni | Italian | Claudia Tarolo | 2000 | OCLC 797691119 |

| 停電の夜に (Teiden no Yoru ni) | Japanese | Takayoshi Ogawa | 2000 | OCLC 48129142 |

| 축복받은집 (Chukbok Badeun Jip) | Korean | Yi Jong-in | 2001 | OCLC 47635500 |

| Vyādhikaḷuṭe vyākhyātāv | Malayalam | Suneetha B. | 2012 | OCLC 794205405 |

| مترجم دردها (Motarjem-e Dard-hā) | Persian | Amir Mahdi Haghighat | 2004 | OCLC 136969770 |

| Tłumacz chorób | Polish | Maria Jaszczurowska | 2002 | OCLC 51538427 |

| Intérprete de emociones | Spanish | Antonio Padilla | 2000 | OCLC 47735039 |

| Den indiske tolken | Swedish | Eva Sjöstrand | 2001 | OCLC 186542833 |

| Dert yorumcusu | Turkish | Neşfa Dereli | 2000 | OCLC 850767827 |

| Người dịch bệnh | Vietnamese | Đặng Tuyết Anh; Ngân Xuyên | 2004 | OCLC 63823740 |

Notes and references

- ↑ Le, C.N. 2009. "The 1965 Immigration Act" at Asian-Nation: The Landscape of Asian America. <http://www.asian-nation.org/1965-immigration-act.shtml> (November 9, 2009).

- ↑ Lahiri, Jhumpa (1999). Interpreter of maladies : stories ([Book club kit ed.] ed.). Boston [u.a.]: Houghton Mifflin. pp. Praise For. ISBN 0-395-92720-X.

- ↑ Noor, Ronny (Autumn–Winter 2004). "Review: Interpreter of Maladies". World Literature Today. 74 (2, English-Language Writing from Malaysia, Singapore, and the Philippines): 365–366.

- ↑ Brada-Williams, Noelle (Autumn–Winter 2004). "Reading Jhumpa Lahiri's "Interpreter of Maladies" as a Short Story Cycle". MELUS. 29 (3/4, Pedagody, Canon, Context: Toward a Redefinition of Ethnic American Literary Studies): 451–464. doi:10.2307/4141867.

- ↑ Ketu H. Katrak, “The Aesthetics of Dislocation”, The Women’s Review of Books, XIX, no. 5 (February 2002), 5-6.

- ↑ Laura Anh Williams, "Foodways and Subjectivity in Jhumpa Lahiri's Interpreter of Maladies," MELUS, Saturday, December 22, 2007.

- ↑ Jhumpa Lahiri, "Cooking Lessons: The Long Way Home." The New Yorker 6 Sept. 2004: 83-84.