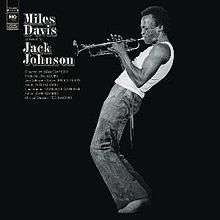

Jack Johnson (album)

| Jack Johnson | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Original LP (Columbia S 30455)[1] | ||||

| Studio album and soundtrack by Miles Davis | ||||

| Released | February 24, 1971 | |||

| Recorded | February 18 and April 7, 1970 | |||

| Studio | 30th Street Studio, New York | |||

| Genre | Jazz-rock, hard rock, funk | |||

| Length | 52:26 | |||

| Label | Columbia | |||

| Producer | Teo Macero | |||

| Miles Davis chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Alternate cover | ||||

Subsequent reissues |

||||

Jack Johnson, later reissued as A Tribute to Jack Johnson, is a 1971 studio album and soundtrack by American jazz musician Miles Davis.[2] In 1970, Davis was asked by Bill Cayton to record music for his documentary of the same name on the life of boxer Jack Johnson.[3] Johnson's saga resonated personally with Davis, who wrote in the album's liner notes of Johnson's mastery as a boxer, his affinity for fast cars, jazz, clothes, and beautiful women, his unreconstructed blackness, and his threatening image to white men.[4] This was the second film score he had composed, after Ascenseur pour l'échafaud in 1957.[5]

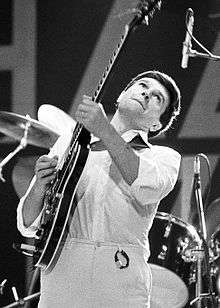

The music recorded for Jack Johnson reflected Davis' interest in the eclectic jazz fusion of the time while foreshadowing the hard-edged funk that would fascinate him in the next few years.[6] Having wanted to put together what he called "the greatest rock and roll band you have ever heard",[7] Davis recorded with a line-up featuring guitarists John McLaughlin and Sonny Sharrock, keyboardists Herbie Hancock and Chick Corea, clarinetist Bennie Maupin, and drummers Jack DeJohnette and Billy Cobham.[6] The album's two tracks were drawn from one recording session on April 7 and edited together with recordings from February 1970 by producer Teo Macero.[8]

Jack Johnson was released by Columbia Records on February 24, 1971.[9] It was a turning point in Davis' career and has since been viewed as one of his greatest works.[6] JazzTimes later wrote that while his 1970 album Bitches Brew had helped spark the fusion of jazz and rock, Jack Johnson was Davis' most brazen and effective venture into rock, "the one that blew the fusion floodgates wide open, launching a whole new genre in its wake".[9] According to McLaughlin, Davis considered it to be his best jazz-rock album.[10]

Recording and production

The first major recording session for the album, which took place on April 7, 1970, was almost accidental: John McLaughlin, awaiting Miles's arrival, began improvising riffs on his guitar, and was shortly joined by Michael Henderson and Billy Cobham. Meanwhile, the producers brought in Herbie Hancock, who had been passing through the building on unrelated business, to play the Farfisa organ. Miles arrived at last and began his solo at about 2:19 on the first track.

The album's two long tracks were assembled in the editing room by producer Teo Macero. "Right Off" is constructed from several takes and a solo by Davis recorded in November 1969. It contains a riff based on Sly and the Family Stone's "Sing a Simple Song". Much of the track "Yesternow" is built around a slightly modified version of the bassline from the James Brown song "Say It Loud – I'm Black and I'm Proud".[12]This may be a deliberate allusion to the song's Black Power theme as it relates to the film's subject. "Yesternow" also incorporates a brief excerpt of "Shhh/Peaceful" from Davis's 1969 album In a Silent Way and a 10-minute section comprising several takes of the tune "Willie Nelson" from a session on February 18, 1970.

"Right Off" comprises a series of improvisations based on a B flat chord, but changing after approximately 20 minutes to an E chord. "Yesternow" has a similar B flat ostinato and shifts to C minor.[13] It concludes with a voiceover by actor Brock Peters: "I'm Jack Johnson, heavyweight champion of the world. I'm black. They never let me forget it. I'm black all right. I'll never let them forget it."[14] Liner notes accompanying a later release of the album provide a description of the music:

| “ | Michael Henderson launches into an enormous boogie groove with Billy Cobham and John McLaughlin. Miles immediately leaves the control room to join in with them. He achieved exactly what he wanted for the soundtrack by creating the effect of a train going at full speed (which he compared to the force of a boxer). By chance, Herbie Hancock had arrived unexpectedly and started playing on a cheap keyboard that a sound engineer quickly connected.[15] | ” |

According to The Guardian's Tim Cumming, Jack Johnson abandoned jazz and the broad textures of Bitches Brew in favor of a concerted take on hard rock and funk, inspired as well by politics, the black power movement, and boxing. "[Davis] had a trainer who travelled with the band", Holland recalled. "He used to go to the gym every day. He was in his 40s, and that's prime time for musicians, when you're strong and all your faculties are there. He was playing incredibly."[8]

Reception and legacy

| Professional ratings | |

|---|---|

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Blender | |

| Boston Herald | |

| Down Beat | |

| The Guardian | |

| MusicHound Jazz | 4.5/5[21] |

| The Penguin Guide to Jazz | |

| PopMatters | 7/10[23] |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| The Village Voice | A+[25] |

Jack Johnson was released in February 1971 by Columbia Records to some commercial success — ultimately peaking at #4 on the Billboard jazz chart and #47 on the magazine's R&B chart – despite little marketing from the label.[26][27] According to Davis, the record was originally released with the wrong cover--a depiction of Johnson in his car, illustrated in stylized period fashion; the intended cover, a photo of Davis playing trumpet in a bent-backward stance, was used on subsequent pressings.[28]

In a contemporary review for The Village Voice, music critic Robert Christgau said that Jack Johnson is his favorite "piece of recording" from Davis since Milestones (1958) and Kind of Blue (1959), and felt that, although it lacks the excitement of the best moments from Bitches Brew, the album coalesces its predecessor's "flashy ideas" into "one brilliant illumination."[25] Steve Starger of The Hartford Courant called the album "magnificent" and "another gem" in Davis' 20-year "string of gems", and wrote that the tracks "really make up one long, churning, steaming, brooding, slashing musical experience that never dips below the highest of art." Starger found the sidemen's performances masterful and said that Peters' voiceover at the end gives "Johnson's words frightening majesty".[14] In a negative review for the Los Angeles Times, Leonard Feather viewed it as a "letdown after the unflawed triumph" of Bitches Brew and was dismayed by Davis for aligning himself with "the thumping, clinking, whomping battering ram that passes for a rhythm section".[13]

In The Penguin Guide to Jazz (2006), Richard Cook later wrote that Jack Johnson "stands at the head of what was to be Miles Davis's most difficult decade, artistically and personally."[22] The Boston Herald cited it as one of Davis' "last truly great albums" and as "some of the most powerful and influential jazz-rock ever played."[18] AllMusic's Thom Jurek wrote of its "funky, dirty rock & roll jazz" and "chilling, overall high-energy rockist stance" while calling it "the purest electric jazz record ever made because of the feeling of spontaneity and freedom it evokes in the listener, for the stellar and inspiring solos by McLaughlin and Davis that blur all edges between the two musics, and for the tireless perfection of the studio assemblage by Miles and producer Macero".[16] John Fordham from The Guardian remarked on the transition in Davis's playing from a "whispering electric sound to some of the most trenchantly responsive straight-horn improvising he ever put on disc". According to Fordham:

Considering that it began as a jam between three bored Miles Davis sidemen, and that the eventual 1971 release was stitched together from a variety of takes, it's a miracle that this album turned out to be one of the most remarkable jazz-rock discs of the era. Columbia didn't even realise what it had with these sessions, and the mid-decade Miles albums that followed – angled toward the pop audience – were far more aggressively marketed than the Jack Johnson set ... Of course, it's a much starker, less subtly textured setting than Bitches Brew, but in the early jazz-rock hall of fame, it's up there on the top pedestal.[20]

In a 2010 interview, American rock musician Iggy Pop said that around 1985, he purchased Davis' 1960 album Sketches of Spain and Jack Johnson in a no frills used record shop for less than $5: "They have been my inspiring companions ever since. The one tears me apart and the other puts me back together."[29]

Track listing

All songs were composed by Miles Davis.

- Side one

- "Right Off" – 26:53

- Side two

- "Yesternow" – 25:34

Personnel

The first track and about half of the second track were recorded on April 7, 1970 by this sextet:

- Miles Davis – trumpet

- Steve Grossman – soprano saxophone

- John McLaughlin – electric guitar

- Herbie Hancock – organ

- Michael Henderson – electric bass

- Billy Cobham – drums

The "Willie Nelson" section of the second track (starting at about 13:55) was recorded on February 18, 1970 by a different and uncredited lineup:

- Miles Davis – trumpet

- Bennie Maupin – bass clarinet

- John McLaughlin – electric guitar

- Sonny Sharrock – electric guitar

- Chick Corea – electric piano

- Dave Holland – electric bass

- Jack DeJohnette – drums

See also

- The Complete Jack Johnson Sessions, a 2003 album of the sessions which produced the Jack Johnson album

References

- ↑ "Album Reviews". Billboard: 44. March 20, 1971. Retrieved June 8, 2013.

- ↑ Leone, Dominique (October 14, 2003). "Miles Davis: The Complete Jack Johnson Sessions". Pitchfork Media. Retrieved July 12, 2016.

- ↑ Szwed 2002, p. 307.

- ↑ Szwed 2002, pp. 307-8.

- ↑ Tingen 2001, p. 100.

- 1 2 3 Pierce, Leonard (December 9, 2010). "Miles Davis : Primer". The A.V. Club. Retrieved September 7, 2013.

- ↑ Tingen 2001, p. 104.

- 1 2 Cumming, Tim (October 16, 2003). "The controversy surrounding Miles Davis's Jack Johnson Sessions". The Guardian. Retrieved September 10, 2013.

- 1 2 JazzTimes. 35 (6-10): 197. 2005.

- ↑ Nicholson, Stuart (October 19, 2003). "Miles Davis, The Complete Jack Johnson Sessions". The Observer. Retrieved May 26, 2016.

- ↑ Christgau, Robert (October 14, 1997). "Miles Davis's '70s: The Excitement! The Terror!". The Village Voice. New York. Retrieved June 10, 2013.

- ↑ MILES BEYOND The Making of Jack Johnson, miles-beyond.com. Archived June 1, 2015, at the Wayback Machine.. Retrieved June 1, 2015

- 1 2 Feather, Leonard (April 11, 1971). "Miles Ahead and Miles Behind". Los Angeles Times. p. C55. Retrieved June 8, 2013.

- 1 2 Starger, Steve (March 27, 1971). "Original Material Helps New Group; Miles Davis Scores on Documentary". The Hartford Courant. p. 14. Retrieved June 8, 2013.

- ↑ French, Alex (December 23, 2009). "We Want Miles: The Q". GQ. Retrieved September 7, 2013.

- 1 2 Jurek, Thom (November 1, 2001). Review: A Tribute to Jack Johnson. AllMusic. Retrieved on 2010-01-13.

- ↑ Pareles, Jon (January 5, 2005). "Review: A Tribute to Jack Johnson". Blender. New York.

- 1 2 K.R.C. (January 23, 2005). "Discs; Rap's new player proves he's ready for big Game". Boston Herald. p. 6.

- ↑ Alkyer, Frank; John Ephland (2007). The Miles Davis Reader. Hal Leonard Corporation. pp. 315–316. ISBN 978-1-4234-3076-6.

- 1 2 Fordham, John (April 1, 2005). Review: A Tribute to Jack Johnson. The Guardian. Retrieved on 2010-01-13.

- ↑ Holtje, Steve; Lee, Nancy Ann, eds. (1998). "Miles Davis". Musichound Jazz: The Essential Album Guide. Music Sales Corporation. ISBN 0825672538.

- 1 2 Cook & Morton 2006, p. 327.

- ↑ Calder, Robert R. (February 24, 2005). "Miles Davis: A Tribute to Jack Johnson". PopMatters. Archived from the original on May 23, 2016. Retrieved May 23, 2016.

- ↑ Considine et al. 2004, p. 215.

- 1 2 Christgau, Robert (June 10, 1971). "Consumer Guide (18)". The Village Voice. New York. Retrieved February 16, 2013.

- ↑ Cook & Morton 2006, p. 328.

- ↑ "Miles Davis - A Tribute to Jack Johnson: Awards", Allmusic.com

- ↑ Szwed 2002, p. 310.

- ↑ Doran, John (October 5, 2010). "My Favourite Miles Davis Album By Lydon, Nick Cave, Wayne Coyne, Iggy & More". The Quietus. Retrieved September 7, 2013.

Bibliography

- Considine, J. D.; et al. (November 2, 2004). Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian, eds. The New Rolling Stone Album Guide: Completely Revised and Updated 4th Edition. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

- Cook, Richard; Morton, Brian (2006). The Penguin Guide to Jazz Recordings (8th ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0141023279.

- Szwed, John F. (2002). So What: The Life of Miles Davis. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0684859823.

- Tingen, Paul (2001). Miles Beyond: The Electric Explorations of Miles Davis, 1967–1991. Billboard Books. ISBN 0823083462.

Further reading

- Cuscuna, Michael (2003). "The Complete Jack Johnson Sessions". Sony Music Entertainment. Archived from the original on March 25, 2006. Retrieved April 13, 2013.

External links

- Jack Johnson at Discogs (list of releases)

- "The Making of Jack Johnson" by Paul Tingen

- "Sound, Mediation, and Meaning in Miles Davis's A Tribute to Jack Johnson" by Jeremy A. Smith (PhD Diss: Duke University, 2008)