Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola

| Vignola | |

|---|---|

|

Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola | |

| Born |

Giacomo (or Jacopo) Barozzi (or Barocchio) da Vignola 1 October 1507 Vignola, in present-day Italy |

| Died |

7 July 1573 (Aged 65) Rome, in present-day Italy |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Known for | Architecture, Garden desigh |

| Notable work |

Villa Farnese Church of the Gesù Villa Lante |

| Movement | Mannerism |

Giacomo (or Jacopo) Barozzi (or Barocchio) da Vignola (often simply called Vignola) (1 October 1507 – 7 July 1573) was one of the great Italian architects of 16th century Mannerism. His two great masterpieces are the Villa Farnese at Caprarola and the Jesuits' Church of the Gesù in Rome. The three architects who spread the Italian Renaissance style throughout Western Europe are Vignola, Serlio and Palladio.

Biography

Giacomo Barozzi was born at Vignola, near Modena (Emilia-Romagna).[1]

He began his career as architect in Bologna, supporting himself by painting and making perspective templates for inlay craftsmen. He made a first trip to Rome in 1536 to make measured drawings of Roman temples, with a thought to publish an illustrated Vitruvius. Then François I called him to Fontainebleau, where he spent the years 1541–1543. Here he probably met his fellow Bolognese, the architect Sebastiano Serlio and the painter Primaticcio.

After his return to Italy, he designed the Palazzo Bocchi in Bologna. Later he moved to Rome. Here he worked for Pope Julius III and, after the latter's death, he was taken up by the papal family of the Farnese and worked with Michelangelo, who deeply influenced his style (see Works section for details of his works in this period).

From 1564 Vignola carried on Michelangelo's work at St Peter's Basilica,[1] and constructed the two subordinate domes according to Michelangelo's plans.

Giacomo Barozzi died in Rome in 1573.[1] In 1973 his remains were reburied in the Pantheon, Rome.

Works

Major Architectural Works

Vignola's main works include:

- Villa Giulia for Pope Julius III, in Rome (1550‑1553). Here Vignola was working with Ammanati, who designed the nymphaeum and other garden features under the general direction of Vasari, with guidance from the knowledgeable pope and Michelangelo. A medal of 1553 shows Vignola's main villa substantially as it was completed, save for a pair of cupolas.

- Villa Farnese at Caprarola (1559–1573);

- Villa Lante at Bagnaia (1566 onwards), including the gardens and their water features and casini;

- Chiesa del Gesù, Rome, the mother church of the Jesuit order, which would become a source for Baroque church facades in the 17th century;

- Basilica of Santa Maria degli Angeli, Assisi (with Galeazzo Alessi);

- Church of Sant'Andrea in Via Flaminia, Rome, the first church to have an oval dome, which became a signature of the Baroque.

- Palazzo dei Banchi, Bologna

Other Architectural Works

- The main courtyard of the Pontifical University of Saint Thomas Aquinas, Angelicum, formerly the convent of the Church of Santi Domenico e Sisto, is traditionally attributed to Vignola but completed after his death. Ten arches on the long sides and seven on the short are sustained by pilasters with Tuscan style ornamentation that rise from high plinths. A simple frieze with smooth triglyphs and metopes separates the lower from the upper levels.[2]

Unbuilt Works

Like many other architects, Vignola submitted his plans for completing the facade of San Petronio, Bologna. Designs by Vignola, in company with Baldassare Peruzzi, Giulio Romano, Andrea Palladio and others furnished material for an exhibition in 2001[3]

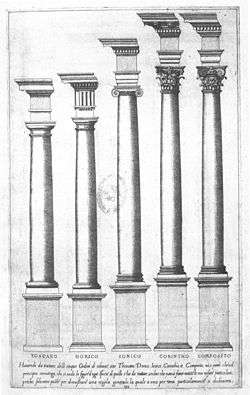

Written Works

His two published books helped formulate the canon of classical architectural style. The earliest, Regola delli cinque ordini d'architettura ["Canon of the five orders of architecture"] (first published in 1562, probably in Rome), presented Vignola's practical system for constructing columns in the five classical orders (Tuscan, Doric, Ionic, Corinthian and Composite) utilising proportions which Vignola derived from his own measurements of classical Roman monuments.[4] The clarity and ease of use of Vignola's treatise caused it to become in succeeding centuries the most published book in architectural history.[5] Vignola's second treatise, the posthumously-published Due regole della prospettiva pratica ["Two rules of practical perspective"] (Bologna 1583), favours one-point perspective rather than two-point methods such as the bifocal construction. Vignola presented— without theoretical obscurities— practical applications which could be understood by a prospective patron.[6]

Notes

- 1 2 3 Chisholm 1911.

- ↑ http://www.romaspqr.it/roma/Fontane/Fontane%20Palazzi%20Cortili/fontana_chiesa_ss_domenico_e_sisto.htm Retrieved 3 May 2013

- ↑ Marzia Faietti and Massimo Medica, 2001. La Basilica incompiuta: Progetti antichi per la facciata di San Petronio (Ferrara: Edisai)

- ↑ Center for Palladian Studies in America, Inc., Palladio's Literary Predecessors

- ↑ Vignola, Canon of the Five Orders of Architecture, translated with an introduction by Branko Mitrovic (New York: Acanthus Press, 1999), p. 17. ISBN 0-926494-16-3.

- ↑ Gietmann 1913.

- Attribution

Gietmann, Gerhard (1913). "Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola". In Herbermann, Charles. Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Gietmann, Gerhard (1913). "Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola". In Herbermann, Charles. Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

References

- Giorgio Vasari, Le Vite... (1568 edition; Volume IV, 94–95).

- G.K. Loukomski, Vignole (Jacopo Barozzi da Vignola) (Series: Les grands architectes), Paris 1927 (Remains a standard monograph).

- Egnatio Danti, Les deux règles de la perspective pratique de Vignole, 1583, Pascal Dubourg Glatigny, Paris, 2003, ISBN 2-271-06105-9.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Barocchio, Giacomo". Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 417.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Barocchio, Giacomo". Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 417.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jacopo Barozzi da Vignola. |

- Website "Architectura", Centre d'études supérieures de la Renaissance, Tours

- Brief biographical sketch

- Paolo Zauli on Vignola from a Bolognese perspective

- Vignola's effect on garden design