James Hargreaves

| James Hargreaves | |

|---|---|

| Born |

13 December 1720 Oswaldtwistle, Lancashire, England |

| Died |

22. April 1778 (aged 57) Nottingham, Nottinghamshire, United Kingdom |

| Nationality | British |

| Education | None |

| Occupation | Inventor |

| Known for | Spinning Jenny |

| Home town | Lancashire |

| Spouse(s) | Elizabeth Grimshaw (m. 1740)[1] |

| Children | 13[1] |

James Hargreaves (c. 1720 – 22 April 1778)[2] was a weaver, carpenter and inventor in Lancashire, England. He was one of three inventors responsible for mechanizing spinning. Hargreaves is credited with inventing the spinning jenny in 1764, Richard Arkwright patented the water frame in 1769, and Samuel Crompton combined the two creating the spinning mule a little later.[3]

Life and work

James Hargreaves was born at Stanhill, Oswaldtwistle in Lancashire. He was described as "stout, broadest man of about five-foot ten, or rather more".[4] He was illiterate and worked as a hand loom weaver during most of his life.[5] He married and baptismal records show he has 13 children,[1] of whom the author Baines in 1835 was aware of '6 or 7'.[4] He was survived by eight children.[1]

Spinning jenny

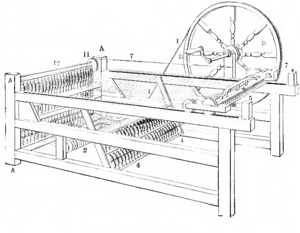

The idea for the spinning jenny is said to have come from the inventor seeing a one-thread wheel overturned upon the floor, when both the wheel and the spindle continued to revolve. He realized that if a number of spindles were placed upright and side by side, several threads might be spun at once. The spinning jenny was confined to producing cotton weft, it was unable to produce yarn of sufficient quality for the warp. High quality warp was later supplied by Arkwright's spinning frame.

Hargreaves produced the Jenny for himself but sold a few to neighbors.[4]

The jenny was initially welcomed by the hand spinners, but when the price of yarn fell the mood changed.

Opposition to the machine caused Hargreaves to leave for Nottingham, where the cotton hosiery industry benefited from the increased provision of suitable yarn. Arkwright also ended up in the town, and was even more successful. Hargreaves made jennies for a man called Shipley, and on 12 June 1770, he was granted a patent, which enabled him to take legal action against the Lancashire manufacturers who had begun using it. This action was withdrawn. With a partner Thomas James, Hargreaves ran a small mill in Hockley and lived in an adjacent house. The business was carried on until his death in 1778 when his wife received a payment of £400.[4] When Samuel Crompton invented the spinning mule in c.1779 he stated he had learned to spin in 1769 on a jenny that Hargreaves had constructed.[6]

Misinformation

As early as 1825, the distinguished author Edward Baines reports that there were many false claims being made about Hargreaves, and Arkwright. There had been a ferocious legal battle to get Arkwright's two most important patents annulled. Thomas Highs of Leigh had claimed that he was the true inventor of both these devices and the spinning jenny as well.[7] In his testimony, Arkwright had over-emphasised the humble nature of both himself and Hargreaves – some of which was not based on fact. He wrongly attributed the date of invention as 1767.[7] Richard Guest opposed Arkwright, and the Edinburgh Review, No. 91[8]reported Guest's opinions and introduced other fallacies. Parish burial registers misspelt Hargreaves as Hargraves, but prove that he did not die in the workhouse.[9] This was confirmed to Baines by Hargreaves's grandson, John James. Parish registers show that neither his wife nor any of his daughters was called Jenny – debunking a myth repeated in school textbooks as late as the 1960s, children's books as late as 2005[10] and to this day on educational websites.[11] The 'jenny' refers to an engine, a common slang term in the 18th century in Lancashire and still to this day used occasionally.

Sources

- 1 2 3 4 "James Hargreaves' Family". Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ↑ "James Hargreaves, or James Hargraves (English inventor) – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- ↑ Timmins 1996, pp. 21,24.

- 1 2 3 4 Baines 1835, p. 162.

- ↑ Allen, Robert C. (December 2009). "The Industrial Revolution in Miniature: The Spinning Jenny in Britain, France, and India". The Journal of Economic History. Cambridge University Press. 69 (4): 907 – via JSTOR. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Baines 1835, p. 159.

- 1 2 Baines 1835, p. 155.

- ↑ Baines 1835, p. 161.

- ↑ Baines 1835, p. 163.

- ↑ Pierce, Alan (2005). The Industrial Revolution. Edina, Minnesota, U.S.A.: ABDO Publishing Company. p. 9. ISBN 9781591979333.

- ↑ e.g. Burchill S.A.

Bibliography

- Hargraves Spinning Jenny – Confined to spinning weft

- Deutsches Museum (auf deutsch) Secondary source.

- Baines, Edward (1835). History of the cotton manufacture in Great Britain;. London: H. Fisher, R. Fisher, and P. Jackson.

- Nasmith, Joseph (1895). Recent Cotton Mill Construction and Engineering (Elibron Classics ed.). London: John Heywood. ISBN 1-4021-4558-6.

- Marsden, Richard (1884). Cotton Spinning: its development, principles an practice. George Bell and Sons 1903. Retrieved 26 April 2009.

- Guest, Richard (1828). The British Cotton Manufactures: and a Reply to an Article on the Spinning Contained in a Recent Number of the Edinburgh Review. London: E. Thomson & Sons and W. & W. Clarke and Longman, Rees, & Co.

- Timmins, Geoffrey (1996), Four Centuries of Lancashire Cotton, Preston: Lancashire County Books, p. 92, ISBN 1-871236-41-X

Further reading

- Abram, W. A. (1877). A History of Blackburn Town & Parish. Blackburn J.G. & J. Toulmin. pp. 204–10.

External links

- Essay from www.cottontown.org on Hargreaves and the Spinning Jenny

- Essay from www.cottontimes.co.uk/