James Muspratt

| James Muspratt | |

|---|---|

James Muspratt | |

| Born |

12 August 1793 Dublin, Ireland |

| Died |

4 May 1886 (aged 92) Lancashire, England |

| Residence | Dublin, Merseyside |

| Nationality | United Kingdom |

| Fields | Chemist, industrialist |

| Notes | |

|

The first to use the Leblanc process commercially | |

James Muspratt (12 August 1793 – 4 May 1886) was a British chemical manufacturer who was the first to make alkali by the Leblanc process on a large scale in the United Kingdom.[1]

Early life

James Muspratt was born in Dublin of English parents, the youngest of three children. At the age of fourteen he was apprenticed to a wholesale druggist, but his father died in 1810 and his mother soon afterwards.[2] He left Dublin and in 1812 he went to Spain to take part in the Peninsular War. He followed the British army on foot into the interior, was laid up with fever at Madrid, and, narrowly escaping capture by the French, succeeded in making his way to Lisbon where he joined the navy. After taking part in the blockade of Brest he deserted because of the harshness of the discipline. [3]

Industry

Returning to Dublin in about 1814, he came into an inheritance and in 1818 established a chemical works in partnership with Thomas Abbott. Here he began to manufacture chemical products such as hydrochloric and acetic acids and turpentine, adding prussiate of potash a few years later.[3]

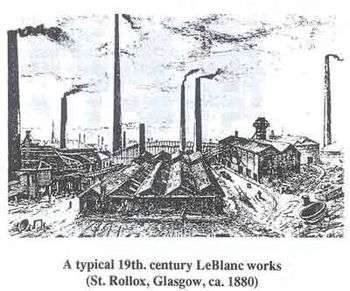

Sodium carbonate, also known as soda ash, is an effective industrial alkali. The manufacture of sodium carbonate from common salt was first developed in France in the 1790s and known as the Leblanc process. Muspratt was attracted towards manufacturing it, but could not raise the capital for the relatively expensive Leblanc plant and also considered that Dublin was not a suitable location for this.[4] He perceived Merseyside as better because of the neighbouring coal fields, the proximity to the salt district of Cheshire, and the proximity to glassmaking industry. The glassmakers were the main prospective customer base for the sodium carbonate alkali.

In 1822 he went to Liverpool and took a lease of an abandoned glass-works on the bank of the Leeds and Liverpool Canal. Though already determined to work the Leblanc process, he did not immediately possess the capital for it, and he therefore continued the production of prussiate of potash, which was profitable, and plough the profits into building the lead chambers and the other necessaries of a complete Leblanc works. Fortuitously in 1823 the duty or tax of £30 per ton was taken off salt. He began to make sodium carbonate alkali by the Leblanc process in 1823.[3][5]

In 1828 he built works at St Helens, (then in Lancashire), in partnership with Josias Gamble, another Irish-born chemist. But after two years the partnership ended and Muspratt moved to Newton-le-Willows, (then in Lancashire).[6] This factory closed in 1851.[7]

He was repeatedly involved in litigation because of the pollution caused. In 1828 he was cited as causing a public nuisance and fined one shilling. In 1831 he was indicted but was acquitted on this occasion.[8] In 1838 after a trial lasting three days, with 40 witnesses for the prosecution and 46 for the defence, a jury found Muspratt guilty of "creating and maintaining a nuisance". At this time he was employing 120 on the Vauxhall Road site which had two chimneys, one of which was 50 yards high.[9]

Retirement

In 1851 Muspratt largely withdrew from the business although he supported his sons, Richard and Frederic in starting new alkali works at Wood End, Widnes and Flint.[10] After his retirement in 1857 his business was continued by his four sons.[3] However, in 1867 he took over the management of Frederic's factory at Wood End before passing it on to another son, Edmund.[11]

In the 1830s he had experimented in producing sodium carbonate alkali by the ammonia-soda process but was unsuccessful.[2][12] In 1834–1835, in conjunction with Charles Tennant, he purchased sulphur mines in Sicily, to provide the raw material for the sulphuric acid needed for the Leblanc process. However, when the Neapolitan government imposed a prohibitive duty on sulphur, Muspratt found a substitute in iron pyrites which was introduced as the raw material for the manufacture of sulphuric acid.[3] Muspratt had been one of the original subscribers to the St Helens and Runcorn Gap Railway in 1833 when he purchased 15 shares at £100 each.[13]

In 1819 he married Julia Josephine Connor with whom he had 10 children, three of whom died in infancy. He built a house, Seaforth Hall on dunes at Seaforth.[14] In 1825 he helped to found the Liverpool Institute for Boys and in 1848 he assisted his son James Sheridan to establish the Liverpool College of Practical Chemistry. He died at Seaforth Hall in 1886 and was buried in Walton, Merseyside, parish churchyard.[2]

External links

A lengthy biography of James Muspratt written in 1906 in a perhaps somewhat too-flowery style, written by J. Fenwick Allen as part of a series entitled Some Founders of the Chemical Industry, presented in two parts:

References

Notes

- ↑ Allen, J. Fenwick (1906), Some Founders of the Chemical Industry, Manchester: Sherrat and Hughes, retrieved 25 August 2009

- 1 2 3 Trevor I. Williams, (2004) ‘Muspratt, James (1793–1886)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press Retrieved on 9 March 2007

- 1 2 3 4 5 James Muspratt, Classic Encyclopedia (based on the 11th edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica (1911)), retrieved 2 July 2007

- ↑ Hardie, p.218.

- ↑ Hardie, pp.12–14.

- ↑ Hardie, pp.21–22.

- ↑ Hardie, p.38.

- ↑ Hardie, p.18.

- ↑ Hardie, pp.19–20.

- ↑ Hardie, pp.38–39.

- ↑ Hardie, p.74.

- ↑ Hardie, p.44.

- ↑ Hardie, p.4.

- ↑ Hardie, p.22.

Bibliography

- Hardie, D.W.F. (1950) A History of the Chemical Industry of Widnes, Imperial Chemical Industries.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Muspratt, James". Encyclopædia Britannica. 19 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 93–94.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Muspratt, James". Encyclopædia Britannica. 19 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 93–94. Hartog, Philip Joseph (1894). "Muspratt, James (1793-1886)". In Lee, Sidney. Dictionary of National Biography. 39. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

Hartog, Philip Joseph (1894). "Muspratt, James (1793-1886)". In Lee, Sidney. Dictionary of National Biography. 39. London: Smith, Elder & Co.