Jean Charles, Chevalier Folard

Jean Charles, Chevalier Folard (February 13, 1669 – March 23, 1752), French soldier and military author, was born at Avignon.

His military ardour was first awakened by reading Caesar's Commentaries, and he ran away from home and joined the army. He soon saw active service, and, young as he was, wrote a manual on partisan warfare, the manuscript of which passed with Folard's other papers to Marshal Belleisle on the author's death.

In 1702 he became a captain, and aide-de-camp to the duke of Vendôme, then in command of the French forces in Italy. In 1705, while serving under Vendôme's brother, the Grand Prior, Folard won the Cross of St. Louis for a gallant feat of arms, and in the same year he distinguished himself at the battle of Cassano, where he was severely wounded. It was during his tedious recovery from his wounds that he conceived the tactical theories to the elucidation of which he devoted most of his life.

In 1706 he again rendered good service in Italy, and in 1708 distinguished himself greatly in the operations attempted by Vendôme and the duke of Burgundy for the relief of Lille, the failure of which was due in part to the disagreement of the French commanders; and it is no small testimony to the ability and tact of Folard that he retained the friendship of both. Folard was wounded at the battle of Malplaquet in 1709, and in 1711 his services were rewarded with the governorship of Bourbourg.

He saw further active service in 1714 Malta, under Charles XII of Sweden in the north, and under the duke of Berwick in the short Spanish War of 1719. Charles XII he regarded as the first captain of all time, and it was at Stockholm that Folard began to formulate his tactical ideas in a commertary on Polybius. On his way back to France he was shipwrecked and lost all his papers, but he set to work at once to write his essays afresh, and in 1724 appeared his Nouvelles découvertes sur la guerre dans une dissertation sur Polybe, followed (1727–1730) by Histoire de Polybe traduite par . . . de Thuillier avec un commentaire de M. de Folard, Chevalier de l'Ordre de St Louis. Folard spent the remainder of his life in answering the criticisms provoked by the novelty of his theories. He died friendless and in obscurity at Avignon in 1752.

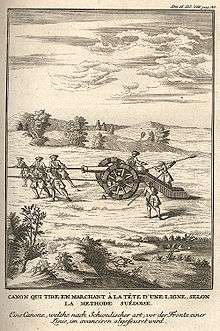

An analysis of Folard's military writings brings to light not a connected theory of war as a whole, but a great number of independent ideas, sometimes valuable and suggestive, but far more often extravagant. The central point of his tactics was his proposed column formation for infantry. Struck by the apparent weakness of the thin line of battle of the time, and arguing from the cuneus of ancient warfare, he desired to substitute the shock of a deep mass of troops for former methods of attack, and further considered that in defence a solid column gave an unshakable stability to the line of battle. Controversy at once centred itself upon the column. While some famous commanders such as Marshal Saxe and Guido Starhemberg approved it and put it in practice, a number of tacticians in France and throughout Europe were opposed to it. Nevertheless, the column (order profond) was put to use by French infantry at several key occasions throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, with varying degrees of success.[1] Among the most discriminating of Folard's critics was Frederick the Great, who is said to have invited Folard to Berlin. The Prussian king certainly caused a prcis to be made by Colonel von Seers, and wrote a preface thereto expressing his views. The work (like others by Frederick) fell into unauthorized hands, and, on its publication (Paris, 1760) under the title Esprit du Chev. Folard, created a great impression.

The 18th-century French historian and political writer Louis-Gabriel Du Buat-Nançay (1732–1787) was his pupil.

References

- ↑ From Myth-Conceived to Myth-Understood: France's Revolutionary Ordre Profond Revisited, http://ordreprofond.blogspot.ca/

Sources

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.