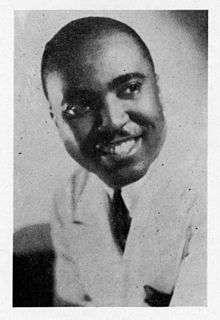

Jimmie Lunceford

| Jimmie Lunceford | |

|---|---|

.jpg) August 1946 | |

| Background information | |

| Born |

June 6, 1902 Fulton, Mississippi, U.S. |

| Died |

July 12, 1947 (aged 45) Seaside, Oregon, U.S. |

| Genres | swing, traditional pop |

| Occupation(s) | Musician, bandleader |

| Instruments | Alto saxophone, flute |

| Labels | Decca, Columbia |

James Melvin "Jimmie" Lunceford (June 6, 1902 – July 12, 1947) was an American jazz alto saxophonist and bandleader in the swing era.

Biography

Lunceford was born on a farm in the Evergreen community, west of the Tombigbee River, near Fulton, Mississippi. The 53 acre farm was owned by his father, James. His mother was Idella ("Ida") Shumpert of Oklahoma City, an organist of "more than average ability." Seven months after James Melvin was born, the family moved to Oklahoma City.[1][2][3] The family next moved to Denver where Lunceford went to high school and studied music under Wilberforce J. Whiteman, father of Paul Whiteman, whose band was soon to acquire a national reputation. As a child in Denver, he learned several instruments. After high school, Lunceford continued his studies at Fisk University.[4] In 1922, he played alto saxophone in a local band led by the violinist George Morrison which included Andy Kirk, another musician destined for fame as a bandleader.[5]

Career

In 1927, while an athletic instructor at Manassas High School in Memphis, Tennessee, he organized a student band, the Chickasaw Syncopators, whose name was changed to the Jimmie Lunceford Orchestra. Under the new name, the band started its professional career in 1929, and made its first recordings in 1930.[6] Lunceford was the first public high school band director in Memphis. After a period of touring, the band accepted a booking at the Harlem nightclub The Cotton Club in 1934 for their revue 'Cotton Club Parade' starring Adelaide Hall.[7][8] The Cotton Club had already featured Duke Ellington and Cab Calloway, who won their first widespread fame from their inventive shows for the Cotton Club's all-white patrons. Lunceford's orchestra, with their tight musicianship and the often outrageous humor in their music and lyrics, made an ideal band for the club, and Lunceford's reputation began to steadily grow.[9] Jimmie Luncefords band differed from other great bands of the time because their work was better known for its ensemble than its solo work. Additionally, he was known for using a two-beat rhythm, called the Lunceford two-beat, as opposed to the standard four-beat rhythm.[10] This distinctive "Lunceford style" was largely the result of the imaginative arrangements by trumpeter Sy Oliver, which set high standards for dance-band arrangers of the time.[6]

Though not well known as a musician, Jimmie Lunceford was trained on several instruments and was even featured on flute in "Liza".[11]

Comedy and vaudeville played a distinct part in Lunceford's presentation. Songs such as "Rhythm Is Our Business" (featured in a 1937 musical short with Myra Johnson (Taylor) on vocals), "I'm Nuts about Screwy Music", "I Want the Waiter (With the Water)", and "Four or Five Times" displayed a playful sense of swing, often through clever arrangements by trumpeter Sy Oliver and bizarre lyrics. Lunceford's stage shows often included costumes, skits, and obvious jabs at mainstream white bands, such as Paul Whiteman's and Guy Lombardo's.

Despite the band's comic veneer, Lunceford always maintained professionalism in the music befitting a former teacher; this professionalism paid off and during the apex of swing in the 1930s, the Orchestra was considered the equal of Duke Ellington's, Earl Hines' or Count Basie's. This precision can be heard in such pieces as "Wham (Re-Bop-Boom-Bam)", "Lunceford Special", "For Dancers Only", "Uptown Blues", and "Stratosphere". The band's noted saxophone section was led by alto sax player Willie Smith. Lunceford often used a conducting baton to lead his band.

The orchestra began recording for the Decca label and later signed with the Columbia subsidiary Vocalion in 1938. They toured Europe extensively in 1937, but had to cancel a second tour in 1939 because of the outbreak of World War II. Columbia dropped Lunceford in 1940 because of flagging sales. (Oliver departed the group before the scheduled European tour to take a position as an arranger for Tommy Dorsey). Lunceford returned to the Decca label. The orchestra appeared in the 1941 movie Blues in the Night.

Most of Lunceford's sidemen were underpaid and left for better paying bands, leading to the band's decline.[11]

Death

After playing McElroy's Ballroom in Portland,[12] Lunceford and his orchestra were in Seaside, Oregon to play at an old wooden skating-rink / dance hall, the Bungalow on July 12, 1947.[13][14] Before the performance Lunceford collapsed during an autograph session at a local record store. He died while being taken by ambulance to the Seaside hospital. Lunceford was 45.[15] Dr Alton Alderman performed an autopsy in nearby Astoria, Oregon, and concluded that Lunceford died of coronary occlusion.[16]

Lunceford had complained about an aching leg as they arrived in Seaside, and had been suffering with high blood pressure for a while, and had recently complained about not feeling well.[17] Allegations and rumors circulated that he had been poisoned by a restaurant owner who was unhappy at having to serve a "Negro" in his establishment.[18] This story is given credence by the fact other members of Lunceford's band who ate at this restaurant were sick within hours of the meal. He was buried at Elmwood Cemetery in Memphis.

Legacy

Band members, notably Eddie Wilcox and Joe Thomas kept the band going for a time but finally had to break up the Jimmie Lunceford Orchestra in 1949.

In 1999, band-leader Robert Veen and a team of musicians set out to acquire permission to use the original band charts and arrangements of the Jimmie Lunceford canon. 'The Jimmie Lunceford Legacy Orchestra' officially debuted in July 2005 at the North Sea Jazz Festival in the Netherlands.

The Jimmie Lunceford Jamboree Festival was founded in 2007 by Ron Herd II a.k.a. R2C2H2 Tha Artivist and Artstorian, with the aim of increasing recognition of Lunceford's contribution to jazz, particularly in Memphis, Tennessee. The Jimmie Lunceford Legacy Awards was created by the Jimmie Lunceford Jamboree Festival to honor exceptional musicians with Memphis ties as well as those who have dedicated their careers to excellence in music and music education.

His music continues to have an impact. Most recently the tune "Rhythm is Our Business" was included as track on the compilation set Memphis Jazz Box in 2004 in honor of Lunceford's close ties to Memphis.

On July 19, 2009, a brass note was dedicated to Lunceford on Beale Street, Memphis, Tennessee.

Selected discography

Prior to Lunceford's success on Decca (beginning September 1934), he made the following recordings:

- "In Dat Mornin'"/"Sweet Rhythm" (Victor V-38141) - recorded Memphis, June 6, 1930

- "Flaming Reeds and Screaming Brass"/"While Love Lasts" (test pressings for Columbia, not released until 1967 on LP) - recorded New York, May 15, 1933

- "Jazznocracy"/"Chillun, Get Up" (Victor 24522) - recorded New York, January 26, 1934

- "White Heat"/"Leaving Me" (Victor 24586) - recorded New York, January 26, 1934

- "Breakfast Ball"/"Here Goes" (Victor 24601) - recorded New York, March 20, 1934

- "Swingin' Uptown"/"Remember When" (Victor 24669) - recorded New York, March 20, 1934

Decca recordings

- Jazz Heritage Series #3- Jimmie Lunceford 1: Rhythm Is Our Business (1934-1935) (LP: Decca #79237, 1968/LP reissue: MCA #1302, 1980)

- Jazz Heritage Series #6- Jimmie Lunceford 2: Harlem Shout (1935-1936) (LP: Decca #79238, 1968/LP reissue: MCA #1305, 1980)

- Jazz Heritage Series #8- Jimmie Lunceford 3: For Dancers Only (1936-1937) (LP: Decca #79239, 1968/LP reissue: MCA #1307, 1980)

- Jazz Heritage Series #15- Jimmie Lunceford 4: Blues In The Night (1938-1942) (LP: Decca #79240, 1968/LP reissue: MCA #1314, 1980)

- Jazz Heritage Series #21- Jimmie Lunceford 5: Jimmie's Legacy (1934-1937) (LP: MCA #1320, 1980)

- Jazz Heritage Series #22- Jimmie Lunceford 6: The Last Sparks (1941-1944) (LP: MCA #1321, 1980)

- Stomp It Off (1934-1935 Decca recordings) (CD: GRP #608, 1992)

- For Dancers Only (1935-1937 Decca recordings) (CD: GRP #645, 1994)

- Swingsation: Jimmie Lunceford (1935-1939 Decca recordings) (CD: GRP #9923, 1998)

Columbia recordings

- Lunceford Special (1939-1940 Columbia recordings) (78rpm 4-disc album set/8 songs/#C-175: 1948; original LP issue/12 songs/#CL-634: 1956; expanded LP reissue/16 songs/#CL-2715 and #CS-9515: 1967; CD release/22 songs/#CK-65647: 2001 from Sony-Legacy label)

Majestic recordings

- Margie (1946-1947 Majestic recordings) (LP/13 songs/#SJL-1209: 1989 from Savoy Jazz label)

The Chronological...Classics series

note: every recording by Jimmie Lunceford & His Orchestra is included in this 10 volume series from the CLASSICS reissue label...

- The Chronological Jimmie Lunceford & His Orchestra 1930-1934 (#501)

- The Chronological Jimmie Lunceford & His Orchestra 1934-1935 (#505)

- The Chronological Jimmie Lunceford & His Orchestra 1935-1937 (#510)

- The Chronological Jimmie Lunceford & His Orchestra 1937-1939 (#520)

- The Chronological Jimmie Lunceford & His Orchestra 1939 (#532)

- The Chronological Jimmie Lunceford & His Orchestra 1939-1940 (#565)

- The Chronological Jimmie Lunceford & His Orchestra 1940-1941 (#622)

- The Chronological Jimmie Lunceford & His Orchestra 1941-1945 (#862)

- The Chronological Jimmie Lunceford & His Orchestra 1945-1947 (#1082)

- The Chronological Jimmie Lunceford's Orchestra 1948-1949 (#1151) -note: these last recordings (1948-1949) were made after Lunceford's death by his long-time band under the joint-direction of Eddie Wilcox (his piano player) and Joe Thomas (his tenor sax player/vocalist).

CD compilations from different reissue labels

- Rhythm Is Our Business (ASV/Living Era, 1992) -note: all tracks recorded 1933-1940, both the Decca and Columbia periods successively.

- It's the Way That You Swing It: The Hits of Jimmie Lunceford (Jasmine, 2002) 2-CD set

- Jukebox Hits 1935–1947 (Acrobat 2005)

- Quadromania: Jimmie Lunceford–Life Is Fine (1935–45, Membran/Quadromania Jazz, 2006) 4-CD box set

- Strictly Lunceford (Proper, 2007) 4-CD box set

- The Complete Jimmie Lunceford Decca Sessions (Mosaic, 2014) 7-CD box set

Trivia

- The Chickasaw Syncopators made a single 78rpm record on December 13, 1927 in Memphis (but without Lunceford); it was issued on Columbia 14301-D.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jimmie Lunceford. |

- ↑ Rhythm Is Our Business : Jimmie Lunceford and the Harlem Express. Eddy Determeyer Ann Arbor : University of Michigan Press, c2006. ISBN 9780472033591. 0472115537 (cloth : alk. paper) pages 1,2

- ↑ "Itawamba History Review: The Itawamba Historical Society: Orchestra Leader Jimmie Lunceford's Itawamba County Roots". Itawambahistory.blogspot.com. 2007-06-05. Retrieved 2013-03-06.

- ↑ http://www.afrigeneas.com/forum-aarchive/index_3.cgi/md/read/id/20788 by Bijan Bayne. Determeyer lists this a resource. retrieved 1.12.2016

- ↑ "Fisk Special Collections Features Music and Manuscript Artifacts in Archives Week Exhibit | Fisk University's Official Weblog". Fiskuniversity.wordpress.com. 2008-10-17. Retrieved 2013-03-06.

- ↑ Dictionary of American Biography, Supplement 4: 1946-1950

- 1 2 "JAZZ A Film By Ken Burns: Selected Artist Biography - Jimmie Lunceford". PBS. Retrieved 2013-03-06.

- ↑ "Cotton Club Revues 1934". Jass.com. Retrieved 2013-03-06.

- ↑ "Underneath a Harlem Moon: The Harlem to Paris Years of Adelaide Hall (Bayou Jazz Lives): Iain Cameron Williams: Books". Amazon.com. Retrieved 2013-03-06.

- ↑ Determeyer, Eddy (2006). Rhythm Is Our Business: Jimmie Lunceford and the Harlem Express. University of Michigan Press. p. 344. ISBN 978-0-472-11553-2.

- ↑ "Jimmie Lunceford". Legends of Big Band Jazz History. Retrieved 2012-11-26.

- 1 2 Yanow, Scott. "Jimmie Lunceford - Music Biography, Credits and Discography". AllMusic. Retrieved 2013-03-06.

- ↑ advertisement The Oregonian July 10, 1947

- ↑ Rhythm Is Our Business : Jimmie Lunceford and the Harlem Express. Eddy Determeyer Ann Arbor : University of Michigan Press, c2006. ISBN 9780472033591. 0472115537 (cloth : alk. paper) page 233, 234

- ↑ http://www.seasidemuseum.org/lunceford.cfm retrieved 1.11.2016

- ↑ Jimmy Lunceford Dies at Seaside. The Oregonian July 13, 1947. page 1

- ↑ Death 'Natural' For Band Leader. (Associated Press) The Oregonian July 16, 1947. page 16

- ↑ Rhythm Is Our Business : Jimmie Lunceford and the Harlem Express. Eddy Determeyer Ann Arbor : University of Michigan Press, c2006. ISBN 9780472033591. 0472115537 (cloth : alk. paper) page233, 234

- ↑ Myers, Mark (July 20, 2011). "Swing's Forgotten King". Wall Street Journal