John and William Merfold

John and William Merfold were yeomen brothers in Sussex, England, in the mid 15th-century. Both were indicted in 1451 after publicly inciting the killing of the nobility, clergy, and the deposition of King Henry VI. They also advocated rule by common people. Minor uprisings spread throughout Sussex until authorities intervened and four yeomen were hanged.

The Merfold statements followed a major rebellion in Kent led by Jack Cade, and are considered demonstrative of underlying class and social conflicts in 15th-Century England.

Background: Social Unrest in 15th-Century England

For 150 years following the onset of the Black Death in 1348-9, England's population, agricultural production, prices, and credit available for trade all declined.[1] This phenomenon reached its apex between 1440-1480, in a downturn known as the Great Slump. Economic activity associated with the wool trade was especially affected, and Kent, Sussex and Wiltshire all suffered during the slump.[1] This situation was aggravated by the final conflicts of the Hundred Years' War, which devastated regions of France critical to English trade, resulted in economic blockades, and caused some to blame Henry VI for their economic hardship.

For artisans or labourers who had previously known greater prosperity, even small fines, chevage, and customary emblems of authority became intolerable.[1] Articles of impeachment from 1449-50 against William, the Duke of Suffolk, suggest that he and other noblemen used their privileged access to the courts and regime to oppress their subjects and advance themselves personally.[2] These injustices and "systematic abuse of power in the king's name" were as egregious in Kent and Sussex as anywhere in England, and led to a series of insurrections. January 1450 saw an uprising by labourer Thomas Cheyne, who called himself "the hermit bluebeard," in Kent. Uprisings followed in February and March.[1] In June, these culminated in a major and unsuccessful rebellion, in Kent, led by Jack Cade, whose forces were able to take London before his defeat.

The uprising was deeply unsettling to the nobility. Without peace and prosperity, complained the Commons, 1450 saw many "murders, manslaughters, rapes, robberies, riots, affrays and other inconveniences greater than before."[3] But the aftermath of the uprising in no way satisfied England's poor. While Henry VI showed clemency to his principal rival Richard Duke of York during the Wars of the Roses, he was merciless to Jack Cade and his followers.[4]

Autumn 1450 Uprisings

Residents of Sussex who had followed Jack Cade and received pardons were hunted by royal forces and either imprisoned or killed. On the 26 July 1450[5] or possibly earlier[6] John and William Merfold, who were "small scale victuallers" from Salehurst,[7] stated in a public market that the king was a natural fool and should be deposed:

[They said] the kyng was a natell fool, and wold ofte tymes holde a staff in his hands with a brid on the ende playing therewith as a fool, and that anoder kyng must be oreyned to rule the land, saying that the kind was no person able to rule the land.— John and William Merfold, Indictment, 1451[5]

The King, Henry VI, would lapse into madness only three years later.[8]

That August a gentleman named William Howell of Sutton encouraged men from the towns of Chichester, Bramber and Steyning to join him in rebellion, and asked that constables and their men join him after "Seynt Bartolomew's day," the 27 August. In September 40 men "armed for war" came to Eastbourne.[9] In October, John Merfold declared in a public alehouse that the people would rise and "wolde leve no gentilman alive but such as thyme list to have."[5] Throughout October and November, men armed with clubs, bows and arrows congregated near Horsham, Robertsbridge and throughout Wealden.[9]

While roving throughout Sussex these bands beat and pillaged from noblemen and clergy, motivated either by class hostility or engaged in petty criminality.[10] At Robertsbridge they objected to dues collected by the local clergy, and at Eastbourne, to high land rents. Rebels at Hastings declared their desire for a new king, and chastised rebels from Kent for capitulation following Jack Cade's rebellion.[9]

Spring 1451 Defeat

During Easter week in the Spring of 1451 men gathered at Rotherfield, Mayfield, and Burwash within Sussex, and in some settlements within Kent.[11] Most were young, and their number included artisans such as carpenters, skinners, masons, thatchers, dyers, tailors, smiths, cobblers, weavers, shingelers, tanners, butchers and shoemakers. Indictments show that only few were agricultural laborers or husbandmen, and fewer still were landless.[11] The rebels demanded that King Henry VI of England be deposed, all lords and higher clergy be killed, and that 12 of their own number be appointed to rule the land. According to indictments prepared at the time,

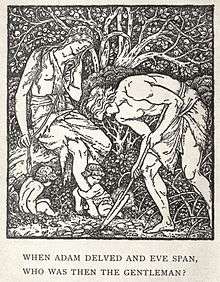

[The rebels wished] as lollards and heretics, to hold everything in common.— The King's Prosecution, Indictment, 1451[11]

Royal authorities responded swiftly by arresting suspected rebels. Four Sussex men were hanged, and resistance broken.[11]

Significance of the Merfold Statements

Most peasant rebellions, including the Peasants' Revolt of 1381, expressed some faith in existing social harmony and the King's willingness to support their cause.[12] One manifesto produced by the Kentish rebellion led by Jack Cade declared, "“we blame not all the lordys… ne all gentyllmen, ne yowmen, ne all men of law, ne all bysshops, ne all prestys, but all such as may be fownde gylty by just and trew enquiry and by the law.”[12] The Sussex revolts of 1450-51 incited by the Merfolds had no such faith in the established social order, and threatened to specifically target lords, bishops, priests, and even in the king.

Historian David Rollison has argued that the socially and politically radical statements by John and William Merfold support the hypothesis that the uprisings were motivated by longstanding class antagonisms.[13] Rollison follows contentions by historian Andy Wood and the 15th-Century English jurist Sir John Fortescue, who have argued that the economic recession of the mid-15th century only magnified routine class antagonisms between village communities and the gentry. The idea that even kings could be disciplined or deposed by popular will was a major aspect of English politics in the centuries following the Magna Carta.[13]

Those in Sussex responding to the Merfolds' declarations were likely motivated by economic and social concerns. These included seigneurial exactions, weeding, reaping and collection duties, all of which were ignored or denounced by yeomen and labourers during the uprisings.[14] Court rolls from Sussex during the period often mention tenant poverty, inability to pay fines or taxes, and abandonment or land or livestock.[14]

Rebels might also have been influenced by Lollard preachers, five of whom were executed in Tenterden, Kent in 1438.[9]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Hicks, 2010, pp.49-55

- ↑ Hicks, 2010, p.38-39

- ↑ Hicks, 2010, p.33

- ↑ Hicks, 2010, p.9

- 1 2 3 Mate, 1992, p.664

- ↑ Sutton, 1995, p.xv

- ↑ Mate, 2006, p.156

- ↑ Hicks, 2010, p.4

- 1 2 3 4 Mate, 1992, pp.664-665

- ↑ Mate, 1992, pp.665-667

- 1 2 3 4 Mate, 1992, pp.666-669

- 1 2 Mate, 1992, pp.663-4

- 1 2 Rollison, 2009, pp.220-232

- 1 2 Mate, 1992, pp.670-72

Sources

- Mate, Mavis (1992). "The economic and social roots of medieval popular rebellion: Sussex in 1450-1451". Economic History Review. 45 (4): 661–676. doi:10.2307/2597413.

- Mate, Mavis (2006). Trade and Economic Developments 1450-1550: The Experience of Kent, Surrey and Sussex. Boydell Press.

- Hicks, Michael (2010). The Wars of the Roses. Yale University Press.

- Sutton, Aland (1995). Rowena E. Archer, ed. Crown, government and people in the fifteenth century. St Martin’s Press.

- Rollison, David (2009). "Class, Community and Popular Rebellion in the Making of Modern England". History Workshop Journal. Oxford University Press: 220–232.