Jose de Mazarredo y Salazar

| Vice-Admiral Don Joseph Mazarredo y Salazar | |

|---|---|

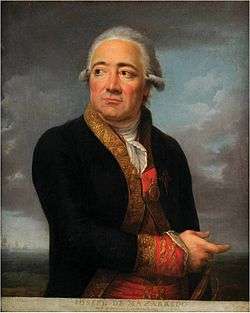

Portrait of Don José de Mazarredo by Jean François-Marie Bellie. | |

| Nickname(s) | El Bilbaíno |

| Born |

8 March 1745 Bilbao, Spain |

| Died |

29 July 1812 Madrid, Spain |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch |

|

| Years of service | 1771–1805 |

| Rank | Admiral |

| Battles/wars |

|

Don Jose de Mazarredo y Salazar de Muñatones Cortázar Order of Santiago (Bilbao 1745 – Madrid, 1812) was a Spanish naval commander, cartographer, ambassador, astronomer and professor of naval tactics. He is considered to be one of the best Spanish naval commanders of all time.

Early life

His inclination toward the sea began at a young age; at 14 he enlisted himself aboard the sloop Andaluz. After 12 years of service in the Spanish navy, and by the good concept his superiors had to him, he was made assistant of the maritime department of Cartagena.

In 1772 Don Mazarredo went to the Philippines aboard the Frigate Venus, but in 1774 he was transferred to the frigate Rosalía and took part in a hydrographic campaign South America.

In 1775 he took part of the Spanish attack on Algiers. The plans of navigation, anchorage and disembarkation of the twenty thousand men of the Spanish army were made by him. Shortly after, Don Mazarredo developed a tabular system for the use of the Spanish Navy.[1] In 1778, as commander of the ship of the line San Juan Bautista, he realised hydrographic surveys in the Iberian Peninsula, contributing to the creation of a Maritime Atlas.

Tactics

Mazarredo was an original theorist. The Spanish Navy entered the American Revolutionary War with a system of tactics devised by him, Teniente de navío de la Real Armada, and expounded in Rudimentos de Táctica Naval para Instruction de los Officiales Subalternos de Marina, printed at Madrid in 1776, dedicated to King Charles III.[2] Despite bearing some evidence of the influence of Paul Hoste and Sébastien Morogues, this is a text book for junior officers, though it could clearly have been read with profit by all alike.[2] In common with the French writers, Mazarredo said very little about fighting the enemy. Broadly speaking, his tone was sophisticated and undogmatic.[2]

Mazarredo did introduce a new sea-warfare idea, the use of fireships by the windward fleet, if threatened with doubling as a means of covering its retreat to windward. Salazar also showed himself an innovator in his treatment of breaking the enemy line. He poroposed that, when the fleet was to windward, the centre should break through the enemy centre.[2] In the process of breaking through, the enemy's centre ships immediately astern of the break would be forced away to leeward, so disorganising the neemy rear and isolating it.[2] Meanwhile, the enemy van would have no choice but to stand on to avoid being put between two fires, and it would thus become completely separated from the remaineder of the fleet.[2]

Exactly the same movement might be executed from leeward, though in that case the enemy's rear would be forced to give way to windawrd, thus exposing itself to the fire of the centre and rear ships of the attacking fleet.[2] Mazarredo also drew up a signal book, specifically for Córdova's fleet, which was printed in 1781.[2] It was used in the operations against Minorca and Gibraltar, and it does not seem unreasonable that Córdova's signalling system was somewhat similar when he first joined comte d'Orvilliers in 1778.[2] Mazarredo's signal book of 1781 is an improvement on Chevalier du Pavillon's.[2] Like the latter, it employed a tabular system, but much less complex. It employed tables 20 yby 20, each permitting 400 signals.[2]

This signal book was prepared for Franco-Spanish cooperation, as it begins with special signals for indicating Spanish and French squadrons, divisions, frigates, the reserve corps, etc. The 400 signals for use at anchor covered not only every feature of fleet administration, as in the manner of Morogues, but also shore bombardments and landings.[2] Twenty special signals allowed for reporting the movements of ships, to be made by privateers. The signals for use under sail by day, made with a combination of 'cornets', which were swallow-tail flags, other flags, and flags from the table, included a series of battle signals. No-one studying this book could criticise the Spanish either for a lack of useful signals for battle and general purposes, or for over elaboration of signalling technique.[2] Although still tied to the tabular system, their arrangement was brilliantly simple compard with that of the French.[2]

American Revolutionary War

As Cordova's Chief of staff he obtained his greatest military achievement.[3] Thanks to his naval knowledge and proposal of a bold manoeuvre, which his colleagues considered reckless,[3] Cordova's fleet of 31 ships of the line and 6 frigates overcame the 55 British ships to Florida in the Action of 9 August 1780, the British ships with 80.000 muskets, many artillery, 300 barrels of gunpowder, more than 1.000.000 pounds in gold and silver, uniforms to more than a dozen regiments, 3000 soldiers and sailors captured, thanks to the secret service of Floridablanca in London, the new troops will desestabilize the war in favor to England.[4][5] Two years later he took part in the indecisive Battle of Cape Spartel. At the end of the American Revolutionary War he was sent to Algiers as ambassador in order to negotiate peace after the Spanish bombardments of Algiers.

French Revolutionary Wars

In 1793 Mazarredo received the military Order of Santiago. During the French Revolutionary Wars Mazarredo's fleet from Cadiz joined Lángara's Squadron in the Mediterranean. During those months Don Mazarredo, who had relieved Lángara did several operations in the Mediterranean Sea, one of them was the evacuation of soldiers and civilians from Roses, a city in the Catalan coast that was being besieged by the French.

Shortly after, Don Mazarredo had written to warn Godoy of the dangers of a Spanish naval decline, accusing the government of bad administration.[6] This cost him to lose his rank, being dismissed and sent to Ferrol weeks later. But after the Spanish defeat in Battle of Cape St Vincent, the admiralty requested his reinstatement.[6] Mazarredo then took command at Cadiz, where a British fleet appeared on 5 July and proceeded to blockade and bombard the city.[6] But Admiral Mazarredo had already organised its defences for such an attack. The Spanish garrison and naval forces put up such a spirited resistance that the British fleet failed to produce any significant losses to the Spanish and went away two days later.[6]

In 1799 Mazarredo left Cadiz and sailed to Cartagena.[7]

Among the news that Napoleon Bonaparte learned that the French Atlantic Fleet, commanded by the Minister of Marine Admiral Étienne Bruix, had entered the Mediterranean and was at Toulon, Bonaparte learned that a Spanish squadron under Admiral Mazarredo had left Cadiz and was at Cartagena.[8] This last bit of news, which presaged a joint Franco-Spanish action in the Mediterranean, should perhaps have induced Bonaparte to remain in Egypt in order to await its issue.[8] Bruix instructions were to co-operate with the Spanish fleet supplying beleaguered Malta and Corfu and then to bring supplies and several thousand reinforcements to Alexandria.[8]

On 21 June 1799, after Bruix helped to evacuate the French from various Italian ports, he joined Mazarredo at Cartagena.[8] The combined Franco-Spanish fleet comprised forty-two battleships. Since the sixty British ships of the line in the Mediterranean were scattered among several squadrons, Bruix had a unique opportunity to expel the British from that sea and take his fleet to Egypt.[8] Mazarredo refused to co-operate with the French in any enterprise save the reconquest of Minorca from Britain. On 30 March the Franco-Spanish fleet sailed from Cartagena to Cadiz. In June 1799, the French and Spanish fleets under Mazarredo and Bruix, amounting to forty sail of the line, and upwards of thirty frigates and smaller vessels, formed a junction at Cartagena, and on 7 July 1799 after an order sent by him, the chasing ships of his Spanish squadron captured the 18-gun hired cutter of the Royal navy Penelope, commanded by Flag Lieutenant Frederick Maitland. After this short action, he proceed from Cadiz to Brest without opposition.[9]

Later years

In 1804 he was sent as ambassador from Spain to France having previously given up the command of the Squadron at Brest to Don Federico Gravina in 1801. His frank bearing and firmness of character were little agreeable to the First consul, who required more flexibility in the agents employed by other powers, with greater difference to his own views and pretensions.[10] It was imperative upon the Spanish court to conciliate the rising power of Napoleon, and Mazarredo soon heard of his recall. Mazarredo had greatly displeased Napoleon by his outspokenness and lack of flexibility, thus he was dismissed to soothe the angry Napoleon, and the subordination of Spanish interest to those of France was complete.[10]

Don Mazarredo called Napoleon's plans "imperialistic and despoistic".[11]

Despite his open criticism of the naval systems at the end of his career, Mazarredo had a well-rounded record of sea time, ship command, commander-in-chief of the corps of marines, and responsible posts as aide to senior Spanish commanders at sea.[12] He conducted several comparative sea trials to perfect ship-handling methods and ships' signalling routines in the San Ildefonso-class. Don Mazarredo is considered to be one of the best Spanish naval commanders of all time.[13][14]

Notes

- ↑ Tracy p.85

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Turnstall p.144

- 1 2 Chartrand p.75

- ↑ Newspaper El Confidencial: http://blogs.elconfidencial.com/alma-corazon-vida/empecemos-por-los-principios/2013-09-07/el-espanol-que-dio-la-mayor-estocada-a-la-bolsa-de-londres_25587/

- ↑ Guthrie p.354

- 1 2 3 4 Chartrand p.5

- ↑ Potter & Nimitz p.136

- 1 2 3 4 5 Herold p. 356

- ↑ Marshall p.384

- 1 2 Stilwell p.112

- ↑ Harbron p.93

- ↑ Hume & Andrew p.57

- ↑ Potter p.147

- ↑ Harbron p.90

References

- Potter, E. B. and J.R. Fredland. The United States and World Sea Power. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, (1955)

- Harbron, John. Trafalgar and the Spanish Navy Conway Maritime Press (2004) ISBN 0-85177-477-6

- Turnstall, Brian. Naval Warfare in the Age of Sail, the evolution of fighting tactics 1650-1815. (1990) Conway Maritime Press ISBN 0-85177-544-6

- Tracy, Nicholas. Nelson's Battles: The Triumph of British Seapower Naval Institute Press (2008) ISBN 1-59114-609-7

- Guthrie, William. A New Geographical, Historical And Commercial Grammar And Present State Of The World. Complete With 30 Fold Out Maps - All Present. J. Johnson Publishing (1808) ASIN B002N220JC

- Chartrand, René. Gibraltar 1779–1783: The Great Siege. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-977-6.

- Chartrand, René. Spanish Army of the Napoleonic Wars (1): 1793-1808 (Men-at-Arms) (v. 1) Osprey Publishing; illustrated edition (1998) ISBN 1-85532-763-5

- John Marshall. Royal Naval Biography; Or Memoirs Of The Services Of All The Flag-Officers, Superannuated Rear-Admirals, Retired Captains, Post-Captains And Commanders.

- Herold J. Christopher. Bonaparte in Egypt Pen and Sword Publishing (2005) ISBN 1-84415-285-5

- Potter, Belmont Elmer & Nimitz, William Chester. Sea power: a naval history

- Andrew, Martin & Hume, Sharp. Modern Spain 1788-1898:The Story Of The Nations Kessinger Publishing, LLC (2007) ISBN 1-4304-8829-8

- Stilwell, Alexander. The Trafalgar Companion Osprey Publishing (2005) ISBN 1-84176-835-9