Joyce Brabner

| Joyce Brabner | |

|---|---|

.jpg) Brabner and Pekar in 1985 | |

| Born |

March 1, 1952 United States |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Spouse | Harvey Pekar (1984-2010; his death; 1 child) |

Joyce Brabner (born March 1, 1952[1]) is a writer of political comics who sometimes collaborated with her late husband Harvey Pekar. Brabner is also a liberal social activist who raised funds via a Kickstarter campaign for a Harvey Pekar Comics as Art and Literature memorial statue and desk, installed October 2012 at the Cleveland Heights Public Library, where the couple often worked. [2][3] She later agreed to help build the Harvey Pekar Park in Cleveland Heights, OH in July 2015:

Brabner stated: "For a few years, now, I’ve been asked to endorse installation of a big, permanent “Harvey Pekar” billboard on a wall in my neighborhood: an image of American Splendor #1 “where it all started.” I’ve always said no. This year, I saw an opportunity and said I would co-operate if a nearby corner was returned to its earlier, youth/arts friendly state by removing the big blocky “people bumper” planters that were installed to discourage assembly– and by welcoming back young people, street musicians, storytellers, chess players, etc. to a communal meeting space and encouraging artists, storytellers and comics makers. The corner is where (young) Harvey used to try out material on the crowd, as a sort of stand up comedian who later wrote and published his stories about neighborhood life in his American Splendor autobio comic books. The spot had been a haven for nonconformist and creative youth until overblown anxiety about flash mobs and kids hanging around without money to support local business led to curfews and what many felt was repressive “rezoning” and redesign. On July 25, Cleveland Heights will turn the space where it really did all start for Harvey into “Harvey Pekar Park,” complete with tiny amphitheater for future “Harveys” and small-scale performance. I’ve designed permanent banners of a special American Splendor story (illustrated by Joseph Remnant) that can be read as you walk from lamp post to lamp post. [4]

Biography

Brabner recalls "read[ing] comics when I was five or six years old - including "Mad Magazine", her first exposure to political satire.[5] Drifting away from comics as she grew older and discovered that "for the same amount of money I could get on the bus and go down to the library," she nevertheless remembered "a lot of what I'd read."[5]

Living "in Delaware working with people in prison, with kids in trouble," running a non-profit culture-based support program for inmates in the Delaware correctional system, Brabner was a founder and manager of "The Rondo Hatton Center for the Deforming Arts," a small theater space in Wilmington, Delaware. (Hatton played horror roles — The Creeper — in the early 1940s without makeup because he was severely disfigured by a glandular disease.)

During this time, Brabner became friendly with "two sometime artists who were very involved in comic fandom", which "seemed like a lot of fun."[5] Feeling burned out from "working with courts, with sexual abusers of children and so on," Brabner began working with Tom Watkins, who "was doing a lot of costumes for the Phil Seuling comic shows."[5] Moonlighting "as a costumer while continuing to work in the prison programs [she] had organized on [her] own," while not spending much time at conventions or comic shops, she nevertheless eventually became co-owner of a comic book (and theatrical costumes) store herself.[5]

Her store stocked Harvey Pekar's American Splendor, but when the store "ran out of an issue" (one of Brabner's partners selling the last copy of American Splendor #6 without her getting a chance to read it), Brabner sent Pekar a postcard directly, asking for a copy, and the two "began to correspond."[5] Developing a phone relationship, after a stay in the hospital by Brabner, Pekar spoke to her daily and sent her a collection of old records.

Harvey Pekar

Brabner recalls that she was:

| “ | "flying out to his [Pekar's] part of the country on other business, and decided to visit him, and the next day we decided to get married!"[5] | ” |

On their second date, they bought rings, and the third date they tied the knot. With the benefit of hindsight, she believes that it was Pekar's honesty that attracted her to him,[6] crediting his work on "American Splendor [for giving her] a worm's-eye view of what his other marriages were like," allowing for a greater degree of understanding and openness between the two of them.[5] It was Brabner's second marriage and Pekar's third.

As Pekar's third wife, she has appeared as a character in many of his American Splendor stories, as well as helping package and publish the various iterations of the comic.[5] Citing her "talent for publicity," Brabner recalls that American Splendor was losing money and decided (having "stopped working for the prison program") to engage in some "screwball publicity."[5] Utilising her costume-making skills, she

| “ | "started cutting up some of his [Pekar's] old clothes and making little Harvey Pekar dolls; just like the Shroud of Turin, they were made with clothing actually worn by the author, like some holy relic. They were these odd collectibles, and I carried these ugly little dolls around at our first San Diego con together.."[5] | ” |

The gimmick worked, and they "picked up nine distributors for the book!"[5] The comic began to be profitable, and one of Brabner's dolls "ended up on 'The David Letterman Show.'"[5] She still makes them occasionally for charity auctions.[5]

In addition to Pekar and American Splendor, Brabner has worked with many of independent comics' highest-profile writers and artists. She edited Eclipse's Real War Stories, which brought Mike W. Barr, Steve Bissette, Brian Bolland, Paul Mavrides, Dean Motter, Denny O'Neil and John Totleben (among others) together on behalf of the Central Committee for Conscientious Objectors and Citizen Soldier.

Real War Stories

Lou Ann Merkle, "an art student and activist living in Cleveland" began working with the Central Committee for Conscientious Objectors, a "military and draft counseling organization" and sought out Pekar for advice on the costs involved in creating a comic.[5] Seeking "a tool to reach teenagers with information about the military" in the face of the peacetime draft and what she saw as an "aggressive recruiting campaign" (aided by the release of Top Gun in 1986).[5] Brabner recalls that Merkle was looking for some "counterpropaganda, a way of presenting some of the things the recruiters weren't telling the kids about the draft," including the stories of "veterans and people from El Salvador."[5]

Although Merkle had only budgeted for a black and white comic, Brabner felt strongly "that color was necessary if they were going to reach the kids," preferably with "popular artists and writers," but "realized with the integrity and honesty the undergrounds had."[5] Brabner, Merkle and the CCCO managed to find a publisher willing to split the costs of printing, were given "some grant funding" and found some creators willing to defer their pay.[5] After publication, the CCCO took on the responsibility of distributing the comic - Real War Stories - including getting copies "into some schools [where] they were used in classrooms".

Legal victory

This drew the attention of the Department of Defense and the Department of Justice, after an Atlanta, Georgia newspaper objected strongly at the "presence of Real War Stories" at a "high school 'career day'."[5] Pressure from "different people from around the country" caused the school to tell the Atlanta Peace Alliance and the CCCO that "they couldn't [attend the career day], prompting the APA and CCCO to file a suit against the school."

At the hearing, the Department of Defense "offered an expert witness" who labelled the contents of Real War Stories as being "all made up," despite Brabner's assertion that not only were they "all autobiographical stories," but that personally "participated in all the interviews [which]... were all carefully documented."[5] During one courtroom exchange, Brabner recalls that they "had military Naval court records" supporting the truth of some of the autobiographical comics stories, and when the case was continued, the "CCCO got a letter from the Department of Defense essentially withdrawing the complaint."[5]

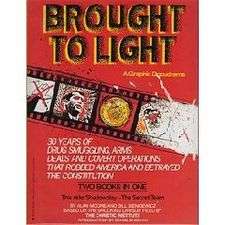

Brought to Light

(Comprising "Shadowplay: The Secret Team" and "Flashpoint: The LA Penca Bombing" (Eclipse Comics)

Her writing on Brought to Light with Alan Moore and artist Bill Sienkiewicz[7] brought critical praise from both the artistic and activist communities. Originally a joint publishing venture between Eclipse Comics and Warner Books, the 1989 graphic novel flip-book Brought to Light dealt in part with the Central Intelligence Agency's involvement in the Iran-Contra affair.[5] The impetus behind Brought to Light was the involvement of the Christic Institute ("a public-interest legal firm, best known at that time for its work on the Karen Silkwood case") in a case "involving the bombing of a press conference in Costa Rica."[5] Survivors of the bombing who had investigated "found," says Brabner "it involved much broader issues involving covert operations [and] possible swaps of drugs for arms."[5]

Stymied in initial attempts to bring the matter to court, the initial investigators required an outside organization, bringing in the Christic Institute.[5] "People at Christic had seen Real War Stories #1" and in trying to raise funds to investigate and document facts and allegations surrounding the "very complicated" story, turned to Brabner "and asked if I could communicate this very complex story in comic book form."[5] Faced with "two ways the stories could be told," Brabner remembers she decided to utilize both.[5]

| “ | I decided to tell these stories in two different ways, as a "topsy-turvy" format comic book. A number of people in comics were too afraid to be involved with the project, but Alan Moore had a story in Real War #1 and I knew we could work together, and he took it on. I wrote the other.[5] | ” |

Warner Books "was interested in the project from the beginning," thinking that they could be involved from the start in a book on the Iran-Contra affair, which could, says Brabner, have been "as big as Watergate."[5] Caution overtook enthusiasm, however, when "it became clear that this story was a lot bigger than everybody thought it was."[5] Although thoroughly scrutinised - and Brabner says that she "was told at the time by Warner's attorneys that our sources were solid and our book would fly" - she believes that Warner "realized this wasn't going to be the enormous trial, or victory, they thought it would be."[5] Ultimately, Brought to Light was published solely by Eclipse.

Other works

Brabner, talking in the early 1990s, described the difficulties involved in "publish[ing] non-fiction, public interest comics," which entail "go[ing] outside the world of comic book publishing," and often relying on "grant money."[5] Even with funding in place, however, she described the difficulty in finding "a publisher willing to take on a reprinting of the Martin Luther King comic Al Capp Studios packaged," which was cited as an inspiration by one of the four students who began the February 1960 "non-violent sit-in demonstration" in Greensboro, North Carolina.[5] Brabner refers to this event as particularly highlighting "the historical role of comics in social and political arenas," and (with American Splendor) "play[ing] a vital role in Joyce's decision to build upon her work in prisons and schools, to apply the medium to controversial investigative ventures."[5] Together, and separately, Pekar and Brabner "have [both] tenaciously pursued a path dedicated to the truths of the human condition, contrary to the lurid escapist fantasies that fuel the main engines of the comic book industry."[5]

Indeed, in the Stephen R. Bissette/Stanley Wiater-edited Comic Book Rebels, the editors draw a distinction between Pekar's stories - which are "primarily by himself and about himself" - and Brabner, who "uses her own experiences to frame broader investigative narratives about America, and the impact our social, political, and military institutions have upon not only ourselves, but the world."[5]

She has also written Activists! and the PETA-supported Animal Rights Comics, as well as working on Strip AIDS and a book called Cambodia, USA.[5] In 1994, Pekar and Brabner collaborated with artist Frank Stack on the Harvey Award-winning graphic novel, Our Cancer Year. Our Cancer Year was, according to Brabner planned to be a "book about activism and cancer and being married and buying a house, about being sick at a time when we feel the whole world is sick."[5] It takes the reader through Pekar's struggles with lymphoma, as well as serving as a social commentary on events of that year, and was, says Brabner, written "together from our different points of view, in the different way we experienced Harvey's illness."[5]

She and Harvey have since published work in Jason Rodriguez's "Postcards" series,[8] as well as an anthology (with Pekar, Ed Piskor and others) on "The Beats" [Farrar, Straus and Giroux 2008].[9]

In addition, Brabner's latest nonfiction comic book, "Second Avenue Caper: When Goodfellas, Divas, and Dealers Plotted Against the Plague" won the 2014 Lambda Literary Award. Illustrated by Mark Zingarelli and published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, the book was published in 2014 by Hill and Wang.[10] With Pekar, she co-authored and appeared as herself in an opera performed by Real Time Opera in January, 2009. The event was broadcast on the Internet from Oberlin College on January 31, 2009. She helped finish and publish two of Pekar's posthumously published works, "Harvey Pekar's Cleveland" (Zip Comics/Top Shelf 2012) and "Not the Israel My Parents Promised Me," (Farrar, Straus and Giroux July, 2012). Also anticipated is a posthumous comic book (with Harvey Pekar), other autobiography by Brabner and new work with Danielle Batone. In 1995, Brabner and Pekar shared a Harvey Award for "Our Cancer Year." In 2011, Brabner was awarded an Inkpot Award in recognition of her work in comics.

Non-writing

In the early 1990s, Brabner and Pekar became guardians of a young girl, Danielle Batone. Danielle became a recurring character in American Splendor, alongside Pekar's diverse cast of family and friends.

Brabner was portrayed by actress Hope Davis in the film adaptation of American Splendor (2003), and also appeared as herself in some scenes. Davis's performance was met with critical acclaim, and she was nominated for the Golden Globe Award for Best Supporting Actress – Motion Picture.

Harvey Pekar died on July 12, 2010.

Select bibliography

- Real War Stories (Eclipse Comics, 1987–91)

- Brought to Light (Eclipse Comics, 1989) ISBN 0-913035-67-X

- Our Cancer Year (Running Press, 1994)

- Activists! (Stabur Press, 1995)

- Animal Rights Comics (Stabur Press, 1996)

- Second Avenue Caper: When Goodfellas, Divas, and Dealers Plotted Against the Plague (Hill and Wang, 2014)

References

- ↑ Miller, John Jackson. "Comics Industry Birthdays", Comics Buyer's Guide, June 10, 2005. Accessed January 1, 2011. WebCitation archive.

- ↑ Kickstarter

- ↑ "Harvey Pekar statue unveiled at library is tribute to the late graphic novelist from Cleveland" by Tom Breckenridge, The Plain Dealer, October 14, 2012.

- ↑ http://www.comicsbeat.com/harvery-pekar-park-dedicated-today-with-fest-installation-in-cleveland/#comments

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 Wiater, Stanley & Bissette, Stephen R. (eds.) "Harvey Pekar & Joyce Brabner By the People, For the People" in Comic Book Rebels: Conversations with the Creators of the New Comics (Donald I. Fine, Inc. 1993) ISBN 1-55611-355-2 pp. 129-141

- ↑ Irvine, Alex (2008), "American Splendor", in Dougall, Alastair, The Vertigo Encyclopedia, New York: Dorling Kindersley, p. 21, ISBN 0-7566-4122-5, OCLC 213309015

- ↑ Armitage, Hugh (September 26, 2011). "'Brought to Light' digitally remastered". Digital Spy.

- ↑ "POSTCARDS Production Blog - An Anthology From Eximious Press" by Jason Rodriguez, July 12, 2006. Accessed August 16, 2008

- ↑ "Macedonia The Book - The Authors: Ed Piskor", by Heather Roberson, 2007. Accessed August 16, 2008

- ↑ Connely, Sherryl (13 November 2014). "Sex, drugs and AIDS: New graphic novel by Joyce Brabner looks at early days of epidemic". NY Daily News. Retrieved 1 July 2015.