Juan Pedro Aladro Kastriota

| Juan Pedro Aladro y Kastriota | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Juan de Aladro de Perez y Valasco August 5, 1845 Jerez de la Frontera, Andalusia, Spain |

| Died |

February 15, 1914 (aged 68) Paris, France |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Other names | Aladro Kastrioti |

| Occupation | Diplomat |

| Known for | Pretender of Albanian Crown |

| Spouse(s) | Juana Renesse y Maelcamp |

| Signature | |

|

| |

Juan Pedro Aladro y Kastriota (1845–1914), known as Aladro Kastrioti between Albanians, born Juan de Aladro de Perez y Valasco,[1] was a Spanish nobleman, diplomat, and pretender of the throne of Albania.[2] He claimed descent from the Kastrioti family through his paternal grandmother, a noblewoman that lived during the era of Charles III. He was referred as Don Aladro.

Life

Born in Jerez de la Frontera, Province of Cádiz in Andalusia in 1845, he was the illegitimate son of Isabel Aladro Pérez and nobleman Juan Pedro Domecq Lembeye. He attended school in his local town until 1862. After that he studied law in Sevilla. In 1867, he entered diplomatic services and was sent as a diplomat of Spain in various parts of Europe, Vienna, Paris (1869), Brussels (1870), The Hague (1872), Bucharest. He reached the top of his career under the era of Alfonso XII. After Alfonso's death he settled in Paris where he lived on income from his winery-estates that his father left him in 1869.[3] He is regarded a sportsman and possessed a remarkable collection of racing horses.[4]

During his diplomatic tours he grew interest in Albanian cause, and started publishing brochures all around Europe and the Mediterranean, including Brussels, Alexandria, Athens, Napoli, Venice, Bucharest, etc. He was a financial contributor to the First Albanian School of Korçë assisting the school to stay open until it was closed by Ottoman authorities.[5] Don Aladro kept contact with Albanian Rilindas and was idealized from some of them as a right heir for a future throne of independent Albania. He visited Sicily and Calabria where he kept contact with the Arbereshe notables in order to support his cause. Aladro visited the Montecassino Abbey searching for documents which supported his claims as a Kastrioti descendant.[4]

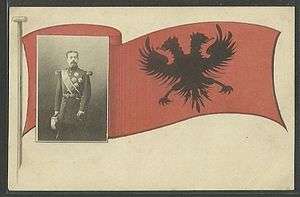

The Albanian politician and scholar Eqrem Bey Vlora, who was close to Don Aladro, states that he claimed descendance from Kastrioti family through a woman from his material side ancestry, related to the noble family of Marchese D'Auletta of Napoli. This woman would have shown up in his dream and order him "Fight for the liberation of Albania, and you'll become its King!". Around 1900, Don Aladro assumed concrete action towards the throne. He founded a literary prize which in 1901 was won by Ndoc Nikaj, a Catholic priest. In 1902, he financed an Albanian student club in Bucharest Shpresa ("The hope"). The same year, he published in Brussels a geographical map of Albania, in cooperation with Faik Konica.[6] Aladro assisted financially the La Nazione Albanese newspaper of the Arbereshe publicist Anselmo Lorecchio, who from his side promoted him back.[7] He also financed a person named Visko Babatasi as his emissary in Albania to distribute money, revolvers, and postcards with Aladro's picture and the Albanian flag, promoting his name though Albanians. This became so evident that the Ottoman authorities prohibited the postcard distribution at a certain point. Many of the postcards are still available today. Babatasi embezzled the funds and went to US.[3] It was said, that the Ottomans offered Aladro the positions of Wali of Shkodra and Yanina Vilayets in order for him to stop agitating the Albanians; Aladro would have requested a full autonomy of all Albania, which Ottomans had rejected.[4]

According to Vlora's Memoirs, the Albanian flag which was raised during the Albanian Declaration of Independence in Vlorë on 28 November 1912 was a gift of 1909 from Don Aladro to him. The official Albanian version stands that Marigo Posio (a native of Korçë residing in Vlorë) embroidered it during the night. Eqrem Vlora confirms that the flag was requested from him by the organizers of the event, and was given to Posio to make copies.[8]

In 1913, the Albanian Congress of Trieste (Trieste back then was part of Austro-Hungaria) was held. Between other things, the congress discussed the name of the future prince. Aladro was one of the candidates, and had some support.[9] But the Great Powers did not like an Catholic candidate for the throne due to Albanian mixed religious nature and to possible opponent from non-Catholic communities (see:Religion in Albania) as well as considered Aladro "a starter" in that direction. Aladro stayed in Paris where he directed a railway company, and died in a hotel in Lamartine Square in 1914.[3]

Beside being e generous person he was a polyglote. Aladro spoke correctly French, Italian, English, German, Castillano, Russian, Albanian, and Euskera (Basque).[2][10] Back home, Aladro was considered a "perfect cavalier, a devoted Christian, an excellent son, and a lover of art".[10]

He collaborated for some time with the newspaper Basque Euskal Erria, ending his articles always with the phrase: Euskalerria aurrera! Shkiperia perpara! ("Forward Euskal Erria! Forward Albania!"). Beside Albania, he showed support for the Basque cause stating that his ancestors partly came from Bidania region.[2] He is the author of a short story written in French, which was translated in Spanish and published in 1912 as Sotir y Mitka (Sotir and Mitka),[3] by Aladro's trusted man Jacinto Ribeyro y Soulés who was also the administrator of Aladro's properties.[10]

Juan Pedro Aladro got married in 1912 in La Teste-de-Buch (in Aquitaine, France) to Juana Renesse y Maelcamp, a Belgian countess, who had been previously married to the deceased Willem Jan Verbrugge, a Dutch nobleman. After Aladro's death without descendants, the widow went to San Sebastián a Jerez, where the Domecq estates were, to close the heritage. She agreed on ceasing the 50% that her husband inherited from his father, in exchange of regular payments for life. She died shortly after.[10]

Honours

Between other:[10]

- Knight of the Order of the Holy Sepulchre

- Knight Grand Cross of Order of Isabella the Catholic

- Commander of the Order of Charles III

- Grand Cross of Order of the Star of Romania

- Grand Cross of Order of St Alexander of Bulgaria

References

- ↑ José López Romero, El jerezano Juan Pedro Aladro Kastriota Príncipe de Albania

- 1 2 3 Iñaki Egaña (2001), Mil noticias insólitas del país de los vascos, TXALAPARTA, p. 210, ISBN 9788481365436

- 1 2 3 4 Robert Elsie (2012), A Biographical Dictionary of Albanian History, I. B. Tauris, pp. 6–7, ISBN 978-1780764313

- 1 2 3 José del Perojo, ed. (1902), "Actualidades", Por esos mundos, 3 (1): 357, OCLC 807152949

- ↑ Nuçi Naçi (1927-03-01), "Shkolla shqipe në Korçë" [Albanian school in Korçë] (PDF), Diturija, Librarija Lumo Skendo, 2: 174, OCLC 699822534,

Ndihmat që mblidheshin në Korçë u-prenë, po Naçi gjeti mburime të tjerë: Aladrua i dërgoj 1,000 Fr. ari, Gjika 500, edhe 1,000 i dërgoj i ndjeri Vasil Terpo, kështu qe financërisht ishte siguruar çelja e vitit shkollar 1901-1902.

- ↑ Fan Stylian Noli (1918), Kalendari i Vatrës i motit 1918 (in Albanian), Boston, MA: Vatra Society, p. 24, OCLC 902699693

- ↑ Antonio D’Alessandri, Un giornalista arbëresh al servizio dell’indipendenza dell’Albania, Universita della Calabria, Laboratorio della Albanologia,

Lorecchio, invece, aveva riposto le sue speranze nel nobile spagnolo Juan de Aladro y Perez de Valasco Castriota, di cui sosteneva la discendenza da Skanderbeg e da cui, inoltre, si faceva finanziare.

- ↑ Sheradin Berisha (2009-12-03), "Kush a nenshkroi aktin a pavaresise se Shqiperise ne Vlore?" [Who signed the Declaration of Independence Act in Vlora?] (PDF), Illyria (in Albanian), New York, 19 (1904): 48,

Eqrem bej Vlora, në kujtimet e tij - thotë se flamuri që u ngrit më 28 Nëntor 1912 në Vlorë, ishte një flamur që e mbaja në shtëpi si kujtim, të dhuruar solemnisht (më 1909) nga një pinjoll i familjes Kastrioti (don Aladro Kastrioti) me banim në Paris.

- ↑ Nopcsa, Franz. "The Congress of Trieste". Robert Elsie. Archived from the original on 2011-03-01. Retrieved 1 March 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Juan Simo Jerez (2013-11-17), El increíble Juan Pedro Aladro Kastriota (in Spanish)