Justus de Harduwijn

| Justus de Harduwijn | |

|---|---|

| Born | April 11, 1582 |

| Died |

June 21, 1636 (aged 54) Oudegem, County of Flanders, Spanish Netherlands |

| Occupation | priest |

| Language | Dutch |

| Alma mater | Leuven University |

| Period | 1613–1635 |

| Genre | poetry |

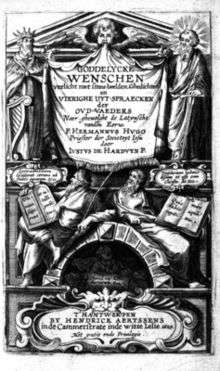

| Notable work | Goddelijcke Wenschen (1629) |

Justus de Harduwijn, also written Hardwijn, Herdewijn, Harduyn or Harduijn (11 April 1582 - Oudegem, 21 June 1636), was a 17th-century Roman Catholic priest and poet from the Southern Netherlands. He was the poetic link between the Renaissance and the Counter-Reformation in the Netherlands.

Life

De Harduwijn was born in a humanist, intellectual family in Ghent. His grandfather Thomas was a steward to Louis of Praet.[1] His father Franciscus owned a bookbinding shop in Ghent and was a member of the Council of Flanders, the highest judicial college in the County of Flanders. His father was a friend of writer Jan van der Noot who had introduced him to the French poets of La Pléiade, and is said to have been the first translator of Anacreon into Dutch.[1] Justus' uncle, Dionysius de Harduwijn, was a historian, and Justus inherited his rich library. The humanist poet Maximiliaan de Vriendt was another uncle of his, and he was also related to Daniel Heinsius.

De Harduwijn studied at the Jesuit college which had recently been established in Ghent. Around 1600 he went to the University of Leuven where he studied under Justus Lipsius and in 1605 became a Bachelor in Law. Subsequently he studied theology at the seminary of Douai. In April 1607 De Harduwijn was ordained a priest, and in December of the same year he became the parish priest of Oudegem and Mespelare, functions which he occupied until his death in Oudegem in 1636.

Work

Justus de Harduwijn became a member of the chamber of rhetoric of Aalst. As a student, he composed the love sonnets De weerliicke liefde tot Roosemond, influenced by the poets of the Pléiade; it was the first book of sonnets written entirely in Dutch, as earlier humanists had written in Latin. It was published anonymously in 1613 by Verdussen in Antwerp, with the poet Guilliam Caudron as the editor.[1]

Influenced by Henricus Calenus and Jacobus Boonen, who would become his patron, De Harduwijn found his inspiration in divine contemplations. In 1614 he wrote Lof-Sanck des Heylich Cruys (Paean to the Holy Cross), a translation of a work by Calenus. In Goddelicke Lofsanghen (Divine Songs of Praise, 1620), dedicated to Boonen, a number of earlier profane poems were reworked. The same year the biblical poetry of Den val en de Opstand van David/Leed-tuyghende Pasalmen (David's fall and rise / Penitential Psalms) was published as well.

His most important work of poetry, Goddelijcke Wenschen (Divine Wishes), appeared in 1629. It was a complete adaptation of the Herman Hugo's Pia desideria (1624). In 1630 Cornelius Jansen, who had just been promoted to professor in Leuven, called upon de Harduwijnto translate the Counter-Reformation pamphlet Alexipharmacum into Dutch. In 1635 de Harduwijn, together with David Lindanus, wrote Goeden Yever tot het Vaderland ter blijde inkomste van den Coninclijcken Prince Ferdinand van Oostenryck (Good Zeal for the Fatherland on the joyous entry of the Royal Prince Ferdinance of Austria), celebrating the Joyous Entry of Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand of Austria as Governor General of the Spanish Netherlands.

Influence

During his life, de Harduwijn was one of the most widely read poets of the Netherlands. He was largely forgotten after his death but was rediscovered in the 19th century by Jan Frans Willems and the writer Johannes M. Schrant. During the 20th century, Oscar Dambre, a literary historian from Ghent, devoted several studies to de Harduwijn, and composer Arthur Meulemans put his text Clachte van Maria benevens het Kruis (Mary's lament by the cross) to music. There are streets name after him in Ghent and in Sittard-Geleen.

Notes

- 1 2 3 Waterschoot, Werner (2000). "Erycius Puteanus and Justus de Harduwijn". Journal of Neo-Latin Studies. Leuven University Press. XLIX: 411. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

Sources

- Oscar Dambre, "Harduwijn (Hardwijn, Hardewijn, Harduyn), Justus de", Nationaal Biografisch Woordenboek, vol. 1 (Brussels, 1964), 599-604.