Kaleb of Axum

| Kaleb Kingdom of Aksum | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| Saint Elesbaan | |

|---|---|

| King of Ethiopia | |

| Born | c. 510 |

| Died | c. 540 |

| Venerated in |

Oriental Orthodox Churches Eastern Orthodox Churches Roman Catholic Church |

| Feast |

|

Kaleb (c. 520) is perhaps the best-documented, if not best-known, king of Axum situated in modern-day Eritrea and North Ethiopia.

Procopius of Caesarea calls him "Hellestheaeus", a variant of his throne name Ella Atsbeha or Ella Asbeha (Histories, 1.20). Variants of his name are Hellesthaeus, Ellestheaeus, Eleshaah, Ella Atsbeha, Ellesboas, and Elesboam, all from the Greek Ελεσβόάς, for “The one who brought about the morning” or “The one who collected tribute.”

At Aksum, in inscription RIE 191, his name is rendered in unvocalized Gə‘əz as KLB ’L ’ṢBḤ WLD TZN (Kaleb ʾElla ʾAṣbeḥa son of Tazena). In vocalized Gə‘əz, it is ካሌብ እለ አጽብሐ (Kaleb ʾƎllä ʾAṣbəḥa).

Kaleb, a name derived from the Biblical character Caleb, is his given biblical name; ʾOn both his coins and inscriptions he left at Axum, as well as Ethiopian hagiographical sources and king lists, he refers to himself as the son of Tazena.[6] He may be the "Atsbeha" or "Asbeha" of the Ethiopian legends of Abreha and Asbeha, the other possibility being Ezana's brother Saizana.

History

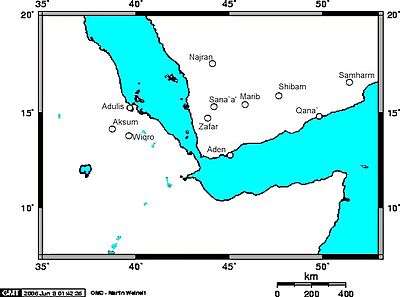

Procopius, John of Ephesus, and other contemporary historians recount Kaleb's invasion of Yemen around 520, against the Jewish Himyarite king Yusuf Asar Yathar (also known as Dhu Nuwas), who was persecuting the Christians in his kingdom. After much fighting, Kaleb's soldiers eventually routed Yusuf's forces and killed the king, allowing Kaleb to appoint Sumuafa' Ashawa', a native Christian (named Esimphaios by Procopius), as his viceroy of Himyar.

As a result of his protection of the Christians, he is known as St. Elesbaan after the sixteenth-century Cardinal Cesare Baronio added him to his edition of the Roman Martyrology despite his being a miaphysite.[7][8][9] However, the question of whether Miaphysitism—the actual christology of the Oriental Orthodox Churches (including the Coptic Orthodox Church)—was a heresy is a question which remains to this day, and other Oriental saints such as Isaac of Nineveh continue to be venerated by the Chalcedonian churches.

Axumite control of South Arabia continued until c.525 when Sumuafa' Ashawa' was deposed by Abraha, who made himself king. Procopius states that Kaleb made several unsuccessful attempts to recover his overseas territory; however, his successor later negotiated a peace with Abraha, where Abraha acknowledged the Axumite king's authority and paid tribute. Munro-Hay opines that by this expedition Axum overextended itself, and this final intervention across the Red Sea, "was Aksum's swan-song as a great power in the region."[10]

Ethiopian tradition states that Kaleb eventually abdicated his throne, gave his crown to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre at Jerusalem, and retired to a monastery.[11]

Later historians who recount the events of King Kaleb's reign include Ibn Hisham, Ibn Ishaq, and Tabari. Taddesse Tamrat records a tradition he heard from an aged priest in Lalibela that "Kaleb was a man of Lasta and his palace was at Bugna where it is known that Gebre Mesqel Lalibela had later established his centre. The relevance of this tradition for us is the mere association of the name of Kaleb with the evangelization of this interior province of Aksum."[12]

Besides several inscriptions bearing his name,[13] Axum also contains a pair of ruined structures, one said to be his tomb and its partner said to be the tomb of his son Gabra Masqal. (Tradition gives him a second son, Israel, whom it has been suggested is identical with the Axumite king Israel.[14]) This structure was first examined as an archaeological subject by Henry Salt in the early 19th century; almost a century later, it was partially cleared and mapped out by the Deutsche Aksum-Expedition in 1906. The most recent excavation of this tomb was in 1973 by the British Institute in East Africa.[15]

The Eastern Orthodox Church commemorates Kaleb as "Saint Elesbaan, King of Ethiopia" on 24 October (O.S.) / 6 November (N.S.).

See also

Notes

References

- ↑ Blessed Elezboi, Emperor of Ethiopia. HOLY TRINITY RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH (A parish of the Patriarchate of Moscow).

- ↑ Blessed Elesbaan the King of Ethiopia. OCA - Feasts and Saints.

- ↑ Synaxarium. Ginbot 20 (May 28). Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Debre Meheret St. Michael Church. Retrieved: 2012-10-30.

- ↑ Synaxarium: The Book of the Saints of The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church. Transl. of Sir E.A. Wallis Budge. Printed by the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Debre Meheret St. Michael Church, Garland, TX USA. p.764.

- ↑ The Roman Martyrology. Transl. by the Archbishop of Baltimore. Last Edition, According to the Copy Printed at Rome in 1914. Revised Edition, with the Imprimatur of His Eminence Cardinal Gibbons. Baltimore: John Murphy Company, 1916. p.331.

- ↑ S. C. Munro-Hay, Aksum: An African Civilization of Late Antiquity (Edinburgh: University Press, 1991), p. 84.

- ↑ Alban Butler; Peter Doyle (1996). "SS Aretas and the Martyrs of Najran, and St Elsebann (523)". Alban Butler. Liturgical Press. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-8146-2386-2.

- ↑ R. Fulton Holtzclaw (1980). The Saints go marching in : a one volume hagiography of Africans, or descendants of Africans, who have been canonized by the church, including three of the early popes. Shaker Heights, OH: Keeble Press. p. 64. OCLC 6081480.

St. Elesbaan was an Aksumite king of Ethiopia who recovered the royal power in Himyar (Yemen) after the massacre of the Martyrs of Najran.

- ↑ Vincent J. O'Malley, C.M. (2001-09-02). Saints of Africa. Huntington, IN: Our Sunday Visitor Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87973-373-5.

- ↑ Munro-Hay, Aksum, p. 88.

- ↑ Munro-Hay, Aksum, pp. 88f.

- ↑ The translation of one inscription, written in Ge'ez, appears with discussion in G.W.B. Huntingford, The Historical Geography of Ethiopia (London: The British Academy, 1989), pp. 63-65.

- ↑ Taddesse Tamrat, Church and State in Ethiopia (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972), p. 26 n. 1

- ↑ Munro-Hay, Aksum, p. 91.

- ↑ The report of the 1973 excavation of these structures was published in S.C. Munro-Hay, Excavations at Aksum (London: British Institute in Eastern Africa, 1989), pp. 42ff.

External links

- Blessed Elesbaan the King of Ethiopia Eastern Orthodox synaxarion

- Elesbaan, king, hermit, and saint of Ethiopia entry from the Dictionary of Christian Biography and Literature to the End of the Sixth Century A.D., by Henry Wace

- Catholic Online: Saint Elesbaan

- Katolsk.no: Elesbaan