Ken Campbell

| Ken Campbell | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Kenneth Victor Campbell 10 December 1941 Ilford, Essex, England |

| Died |

31 August 2008 (aged 66) Loughton, Essex, England |

| Years active | 1961–2008 |

| Spouse(s) | Prunella Gee (1978–83) |

| Website |

TentRinger |

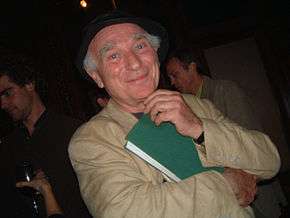

Kenneth Victor Campbell (10 December 1941 – 31 August 2008) was an English writer, actor, director and comedian known for his work in experimental theatre.[1] He has been called "a one-man dynamo of British theatre."[2]

Campbell achieved notoriety in the 1970s for his nine-hour adaptation of the science-fiction trilogy Illuminatus! and his 22-hour staging of Neil Oram's play cycle The Warp. The Guinness Book of Records listed the latter as the longest play in the world.[3][4]

The Independent said that, "In the 1990s, through a series of sprawling monologues packed with arcane information and freakish speculations on the nature of reality, he became something approaching a grand old man of the fringe, though without ever discarding his inner enfant terrible."[5] The Times labelled Campbell a one-man whirlwind of comic and surreal performance.[6]

The Guardian, in a posthumous tribute, judged him to be "one of the most original and unclassifiable talents in the British theatre of the past half-century. A genius at producing shows on a shoestring and honing the improvisational capabilities of the actors who were brave enough to work with him." [7] The artistic director of the Liverpool Everyman and Playhouse said, "He was the door through which many hundreds of kindred souls entered a madder, braver, brighter, funnier and more complex universe." [8]

Early life and career

Campbell was born in Ilford, Essex, the son of Elsie (née Handley) and Anthony Colin Campbell, who was a telegrapher.[9] He staged his first performances in the bathroom of his childhood home: "I was three years old and helped by my invisible friend, Peter Jelp, I put on shows for the characters in the linoleum." [10]

He was educated at Chigwell School (where he won the Drama prize) and then studied at RADA before joining Colchester Repertory theatre as an understudy to Warren Mitchell. In 1967 he became resident dramatist and acting company member at the Victoria Theatre, Stoke-on-Trent.[11] He soon began writing and directing his own productions, including working with director Lindsay Anderson. After seeing the American Living Theatre at The Roundhouse in the early 1970s he was inspired to found The Ken Campbell Roadshow, a small theatre group that performed in unconventional venues such as pubs. Members included Bob Hoskins and Sylvester McCoy. Campbell was invited by John Cleese to appear with his Roadshow team in the first Secret Policeman's Ball in June 1979.

Theatre director and playwright

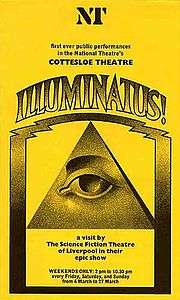

In 1976, he and Chris Langham formed the Science Fiction Theatre of Liverpool in order to stage Illuminatus, a nine-hour cycle of five plays by himself and Langham based on the cult trilogy of avowedly anarchist science fantasy novels of the same name by Robert Shea and Robert Anton Wilson. Starring Campbell and Langham themselves, the production featured Neil Cunningham, David Rappaport, Jim Broadbent, Bill Nighy and Campbell's future wife Prunella Gee. It later moved to the National Theatre, where it opened the new Cottesloe Theatre in 1977.

Sir Peter Hall, director of the National at the time, writes of Campbell in his Diaries, "He is a total anarchist and impossible to pin down. He more or less said it was a crime to be serious." [12]

The Warp, based on the real life experiences and adventures of author Neil Oram, is a dizzying trek through the nether reaches of gurudom and tireless post-sixties mind-expansion, directed by Ken Campbell, and opened at London's Institute of Contemporary Arts in January 1979. It was spawned by the encounter between Oram and Campbell after Oram gave his acclaimed performance as raconteur at the ICA. Campbell commissioned the cycle of ten plays after hearing Oram. The cycle's inordinate length when (as was intended to be possible) it is played together, 22 hours, rendered the 9-hour Illuminatus! a mere bagatelle by comparison. For the first two weeks the performances were of one play per night, after which the impetus for a marathon performance, a real challenge to actors and audience, became irresistible. The success of this remarkable effort by all concerned led to three full marathon performances at the ICA. Five marathon performances followed at the Roundhouse in London in November 1979 also directed by Ken. Probably the most remarkable, and in terms of the ethos of the author and the work, the most attractive event in this episode was the five marathons that were performed, against the wishes of an army of local officialdom, during a squat of the Regent Theatre in Edinburgh during the Festival of 1979. The Scottish audiences were as enthusiastic as the London crowd. After one performance at Hebden Bridge in Yorkshire, a further performance was given at Liverpool Everyman Theatre in a ten-week run from 29 September – 6 December 1980. Cult status was established giving some credence to the publicity material - "The world may soon divide into those who have been through THE WARP and those who have not" More recently the cycle was revived in the 1990s in a production directed by Campbell's daughter Daisy.

In May 1979, again at the ICA, the company presented the first stage version of The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy. One eye-popping aspect of the production was that for each set change the entire audience was wafted 1/2000th-of-an-inch above the floor aboard an industrial hovercraft. The cast cavorted on various ledges and platforms. The craft's carrying capacity meant that audiences were limited to a maximum of eighty each night. Langham was Arthur Dent, Richard Hope as Ford Prefect and narration of The Book was split between two usherettes. The problem of how to portray Zaphod Beeblebrox, the Betelgeusian blessed with three arms and two heads - not an issue in the original radio series - was assailed in typical Campbell fashion by simply (or not so simply) putting two actors inside one large costume.

Audience-carrying capacity was not a problem at London's vast Rainbow Theatre where Campbell mounted a yet more grandiose version of The Hitchhiker's Guide in July 1980. The venue had been renovated in the 1970s to take rock operas. Some reviewers, who in general did not greet the show favourably, labelled it a musical, since it now came with incidental music and audacious laser effects. It ran for over three hours and, despite attempts to shorten the script, was forced to close some four weeks early, in the process losing a lot of money.

For a year, 1980–1981, Campbell was artistic director of the Liverpool Everyman Theatre. From 1984, he made repeated efforts to adapt for the stage VALIS, the largely autobiographical cult science fiction novel by Philip K. Dick, but to the disappointment of fans, these efforts came to nothing.

Television, radio and film

Campbell played Alex Gladwell, a corrupt lawyer, in one of the TV events of the 1970s, Law and Order, the notorious but ground-breaking corruption drama by G.F. Newman, a luminary of British TV screenwriting. The series provoked such a press outcry at the time that the BBC banned its overseas sale, since it was deemed to have portrayed Britain's police and criminal justice system in such a wholly unfavourable light.

He played Alf Garnett's neighbour, Fred Johnson in the half-dozen series of the 1980s sitcom In Sickness and in Health, which had the effect of cementing his career-long friendship with Warren Mitchell. He was memorable in Jack Pulman's 1981 television series Private Schulz as the acerbic Herr Krauss, an underwear factory owner hoping the war would continue so as not to jeopardise his contracts with the German army.

Campbell in 1987 unsuccessfully auditioned for the part of the seventh doctor in Doctor Who. He was beaten to the role by his old protégé Sylvester McCoy. The then script editor, Andrew Cartmel, later revealed that Campbell's interpretation had been considered "too dark" to put on television. Other roles included the children's programme"Erasmus Microman" on ITV from 1988-89 being a mad scientist. He was also the irritating Roger in "The Anniversary" episode of Fawlty Towers and buck-toothed blackmailer Ted Goat in Lovejoy Loses It, a 1993 episode of Lovejoy.

Campbell's radio career included playing Poodoo in The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, a part specifically written for him. The Radio 3 literary programme The Verb included Campbell as a regular contributor; in such spots as Campbell's Book Soup he became an upturner of bibliographic rocks, revealing unconsidered trifles to the hilarity of fellow contributors.

His film work included Derek Jarman's The Tempest (1979), Breaking Glass (1980), Joshua Then and Now (1985), The Bride (1985), Chris Bernard's Letter to Brezhnev (1985), Peter Greenaway's A Zed and Two Noughts (1985), Charles Crichton's A Fish Called Wanda (1988), Alice in Wonderland (1999), Saving Grace (2000) and Creep (2004).

In the final years of his life Campbell suddenly found himself cast in a whole new TV role: that of doggedly curious sceptic called upon to probe the outer realms of particle physics and cognitive science on behalf of the casual viewer, particularly where the science bordered on the paranormal. Campbell's idiosyncratic presentation in Brainspotting, Reality On the Rocks and Six Experiments that Changed the World, each made for Channel 4, owed much to the influence of one of his heroes, the American iconoclast Charles Fort. Campbell became a star turn at the annual Fortean Times convention, UnCon.

Later career and one-man shows

From the late eighties onwards Campbell wrote and performed a series of one-man shows, each a mélange of autobiographical stand-up comedy, ontological speculation and popular-science rant. They include Recollections of a Furtive Nudist, Jamais Vu, Mystery Bruises and Pigspurt. Several were published by Methuen. He toured them worldwide. Three of them were performed together at the National Theatre in 1993, as The Bald Trilogy: Furtive Nudist, Jamais Vu and Pigspurt.[13]

Campbell was later commissioned by the National's director Trevor Nunn to write The History of Comedy Part One: Ventriloquism. The two had previously fallen out when Nunn had been director of the Royal Shakespeare Company in 1981. Campbell had carefully concocted a press release and a string of personal letters complete with forged signature: Nunn appeared to be announcing that henceforth, as a consequence of the huge success of its recent adaptation of Nicholas Nickleby, the Royal Shakespeare Company would be changing its name to the Royal Dickens Company. Several grandees of the English theatre had been taken in by the hoax. Only when an exasperated Nunn called in Scotland Yard did Campbell finally own up.

In 1999, Campbell starred with Warren Mitchell and John Fortune in Art in London's West End.

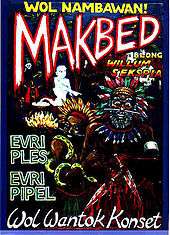

In 2001 Campbell staged a version of Macbeth in pidgin English. It was the big gun in his campaign to get Bislama, first language of 6,000 inhabitants of the South Pacific islands of Vanuatu, formally adopted as a world language (wol wantok). The virtue of Bislama was that with a bit of determination you could pick it up in an afternoon. Campbell argued that, in certain respects, Macbeth in pidgin was better than the original. If nothing else, the campaign had the effect of bringing to a wider public the Bislama for Prince Philip: Nambawan bigfala emi blong Misis Kwin ("Number one big fellow him belong Mrs Queen").

With Alan Moore, Bill Drummond, Mixmaster Morris and Coldcut, he appeared at the Royal Festival Hall in 2007 in a memorial tribute to Robert Anton Wilson, co-author of the Illuminatus! novels.[14]

In July 2008 Staffordshire University awarded Campbell an honorary doctorate, labelling him one of Staffordshire's "greatest living success stories", a reference to his time as artist in residence in 1967 at Stoke-on-Trent's Victoria Theatre.[15]

Campbell appeared on 6 September 2009, over a year after his death, in the first of a new series of Marple on ITV. He played Crump; his wife was played by Wendy Richard.

The School of Night

On 23 April 2005, Ken Campbell was asked by Mark Rylance, the artistic director of Shakespeare's Globe, to stage a celebration of Shakespeare's work. Campbell responded with Shall we Shog?, a show in which actors played competitive improvisational games against each other in the idiom of Shakespeare. These included games like 'flyting' (a tournament of increasingly outrageous insults); an explanation and demonstration of the 'Nub' (a piece of poetic-sounding doggerel an actor uses to give himself a breathing space when he has forgotten his lines - the first sentence should contain the word 'nub' to warn the others that the actor is in trouble, and it should end with the words "Milford Haven"); and fastest recitation of Hamlet's To be, or not to be soliloquy; among many others.

Campbell continued working with some of the actors from Shall We Shog, shedding and adding more along the way. He presented a series of literary improvisation shows, including a run at The Royal Court called Décor Without Production, in which the cast would create scenes and songs in the styles of poets, playwrights, novelists and songwriters.

In 2006 Campbell worked with Adam Meggido's theatre company the Sticking Place (now Extempore Theatre) and staged a run of In Pursuit of Cardenio at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe, during which the cast were supposed to re-create a lost Shakespeare play through improvisational techniques. In practice it turned into a nightly-changing series of literary challenges for the performers. By the latter part of the run, a large section of the show was devoted to improvised songs. One example of the extent to which Campbell pushed the actors was that by the end, each member of cast had developed four musical styles in which they could improvise, each corresponding to a different Elizabethan humour. They would then perform fully sung-through scenes, swapping humours and song styles mid-sentence as the scene or Campbell demanded.

The Cardenio shows used Campbell's now well-established "Goader and Rhapsodes" technique, in which the goader (Campbell) pushed the rhapsodes (the cast) into feats that they would not be able to achieve without the pressure he could apply.

The group eventually consolidated and settled on the name "The School of Night", after Sir Walter Raleigh's secret society. Raleigh's School of Night (also called The School of Atheism) was a group of highly literate and intellectual men who would meet to discuss forbidden topics. Campbell's take on it was that the group, which included playwrights and poets, were steeped in the art of extemporisation and would create from scratch, in perfect meter, plays and poems.

Campbell's School of Night group has become well known in the improvisational theatre and comedy scene, putting on shows and workshops and appearing in festivals as far afield as Elisnore Castle, the Wiesbaden Summer Improv Festival and the Improvaganza festival in Edmonton, Canada, the Edinburgh Festival Fringe; and returning several times to Shakespeare's Globe.

In 2007, the work on singing in various styles of music that Campbell developed also led two of the members of the School of Night—Adam Meggido and Dylan Emery—to develop an improvised musical. The resulting show, which while not directed by Campbell, was enormously influenced by him, became Showstopper! The Improvised Musical. Its first run in Edinburgh was in 2008; it returned in subsequent years and has become something of a fringe institution. The show continues to tour and has had a BBC Radio 4 series. A West End run in 2016 won the Olivier for Best Entertainment and Family.

Campbell performed with The Showstoppers in August 2008 in their second Edinburgh Fringe, reprising his School of Night role as on-stage director of proceedings in the final six shows of the run. For these performances, instead of taking suggestions from the audience regarding the setting and title of the show, Campbell had previously asked a number of professional theatre critics to each write a review of an imaginary musical; after this review was read onstage, the company's task would be to realise the show whose details they had only just heard. Campbell's last performance was on 24 August 2008, one week before he died.

Personal life

Campbell married the actress Prunella Gee in 1978, and they had a daughter, Daisy. They divorced in 1983 but remained close friends.[10] He was in a relationship with the ventriloquist and actress Nina Conti when she was 26 and he was 59; from him she inherited his collection of ventriloquist dummies.[16][17][18][19]

Campbell lived in Loughton adjacent to Epping Forest in a nineteenth-century Swiss chalet. His funeral, a woodland burial in Epping Forest, was attended by a distinguished roll of guests with whom he had worked in the theatre.[20]

Bibliography

- 1972 - You See the Thing Is This: A One Act Comedy (ISBN 0-237-74966-1)

- 1972 - Old King Cole (ISBN 1-870259-12-2)

- 1975 - Skungpoomery (ISBN 0-413-67520-3)

- 1976 - Jack Sheppard (ISBN 0-333-19623-6)

- 1991 - Recollections of a Furtive Nudist (ISBN 1-871503-03-5)

- 1993 - Pigspurt: Or Six Pigs from Happiness (ISBN 0-413-68100-9)

- 1995 - The Bald Trilogy (ISBN 0-413-69080-6) - a volume collecting together Furtive Nudist, Pigspurt and Jamais Vu

- 1996 - Violin time; or, the Lady from Montségur (ISBN 0-413-70960-4)

- 2000 - Wol Wantok (ISBN 1-84166-039-6) - a pidgin English version of Macbeth

- 2011 - Coveney, Michael, Ken Campbell: The Great Caper, Nick Hern Books, London (ISBN 978-1-84842-076-2)

- 2011 - Merrifield, Jeff, Seeker! Ken Campbell: His Five Amazing Lives, Playback Publications, Shetland (ISBN 978-0-9558905-4-3)

References

- ↑ Hanman, Natalie (1 September 2008). "Improv king Ken Campbell dies". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2008-09-01.

- ↑ Newfoundland newspaper, The Scope, 10 September 2008

- ↑ Ian Shuttleworth. "THE WARP: Introduction". Compulink.co.uk. Retrieved 2009-08-16.

- ↑ "World's longest play. Neil Oram The Warp". Thelongestlistofthelongeststuffatthelongestdomainnameatlonglast.com. Retrieved 2009-08-16.

- ↑ "Ken Campbell: Actor, writer and director famed for his epic plays and one-man shows - Obituaries, News". London: The Independent. 3 September 2008. Retrieved 2009-08-16.

- ↑ "Ken Campbell oneman whirlwind of comic and surreal performances". The Times. London. 2 September 2008. Retrieved 2010-05-07.

- ↑ Coveney, Michael (1 September 2008). "Obituary: Ken Campbell | Stage | guardian.co.uk". London: Guardian. Retrieved 2009-08-16.

- ↑ "Liverpool Everyman & Playhouse Theatres - News". Everymanplayhouse.com. Retrieved 2009-08-16.

- ↑ "Ken Campbell Biography (1941-)". Filmreference.com. 10 December 1941. Retrieved 2009-08-16.

- 1 2 "Ken Campbell". London: Telegraph. 1 September 2008. Retrieved 2009-08-16.

- ↑ Staff writer (July 2008). "Ken Campbell". Honorary Doctors. University of Staffordshire. Archived from the original on 28 April 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-14.

- ↑ Peter Hall, Diaries, 1983, p.284

- ↑ http://www.nationaltheatre.org.uk/8207/past-events/past-productions-19911995.html

- ↑ "Robert Anton Wilson 1: Ken Campbell intro". YouTube. 28 September 2007. Retrieved 2009-08-16.

- ↑ Staff writer (July 2008). "Staffs Uni Announces Honours List". University of Staffordshire. Retrieved 2009-05-14.

- ↑ 'The ventriloquist who found her voice: Tom Conti's daughter on how her affair with a much older man gave her the confidence to go on stage' Daily Mail 12 July 2012

- ↑ 'Nina Conti: The acclaimed ventriloquist on the seductions of acting and throat-singing' The Independent 5 May 2013

- ↑ 'Nina Conti: A Ventriloquist's Story, BBC4 – review' Radio Times 13 June 2012

- ↑ 'Nina Conti: 'I feel it's not in my film how much I miss Ken' The Guardian 15 March 2012

- ↑ Coveney, Michael (10 September 2008). "A fond farewell in Epping Forest". Whatsonstage.com. Retrieved 2009-10-13.

External links

- Campbell on BBC Radio 3, on the Library of the Peculiar & Jeremy Beadle

- 1977 Fanatic special issue for Campbell's stage version of Illuminatus! and Fortean Times coverage

- Jeff Merrifield on putting Illuminatus! on stage

- Macbeth in pidgin English, 1998

- Background to The Warp and full script

- Recording of performance in Manchester of The Captain sequence from Pigspurt, December 1992

- Ken Campbell at the Internet Movie Database

Interviews

- 2004 recording of Campbell on the origins of Science Fiction Theatre of Liverpool

- Interview with James Nye, 1991

- Guardian interview, 2005

- Guardian interview about Campbell's work in theatrical improvisation, 2005

Obituaries

- Michael Billington, The Guardian, with tributes from friends and fans, 1 September 2008

- Michael Coveney, The Guardian, 1 September 2008

- The Daily Telegraph, 1 September 2008

- Ian Shuttleworth, The Financial Times, 3 September 2008

- Fortean Times, November 2008

- Mark Borkowski, Chortle, UK comedy website, 1 September 2008

- Thompson's Bank of Communicable Desire - includes audio on origin of the pidgin Macbeth & the One-Minute Warp

- Gemma Bodinetz, artistic director of the Liverpool Everyman & Playhouse

- What's on Stage tribute from Simon McBurney of Complicite

- The Fortean Institute

- The Independent, 3 September 2008

- The Times, 1 September 2008

- Liverpool Confidential

- Oblomovka Danny O'Brien

- BBC News

- BBC Radio 4's Last Word

- My Much-Missed Madcap Friend by Richard Eyre, The Guardian, 11 October 2009