Gyōji

A Gyōji (行司) is a referee in professional sumo wrestling in Japan.

Gyōji usually enter the sumo world as teenagers and remain employees of the Sumo Association until they retire aged 65. There are currently a little over 40 active gyōji with an average of one in each sumo stable, though some stables have more than one and some have no gyōji.

Responsibilities

The gyōji's principal and most obvious task is to referee bouts between two sumo wrestlers. After the yobidashi has called them into the ring it is his responsibility to watch over the wrestlers as they go through the initial prebout staring contests, and then coordinate the initial charge (or tachi-ai) between the wrestlers. He will indicate that the preparation time (four minutes for the top division) is up by saying "jikan desu, ryote wo tsuite" ("it's time, both hands down") and signal with his fan that the bout is to begin (although it is the wrestlers that ultimately determine the exact point at which the tachi-ai is initiated). He will sometimes add, "kamaete mattanashi!" ("on your marks, no false starts!") During the bout, he is supposed to keep the wrestlers informed that the bout is still live (it is possible for a wrestler to brush his foot outside the ring without realising it). He does this by shouting "nokotta nokotta!" (残った、残った!), roughly translated means: "You're still in it! You're still in it!" The gyōji also has the responsibility to encourage the wrestlers to get a move on when action between them has completely stopped, for instance, when both of them are locked up on each other's mawashi in the middle of the ring. He will do this by shouting "hakkeyoi, eh! hakkeyoi, eh!" (発気揚々, 発気揚々!). Furthermore, when a wrestler has apparently fallen to the clay, the gyōji is expected to determine the winner of the bout. His most obvious accessory is a solid wooden war-fan, called a gunbai which he uses in the prebout ritual and in pointing to the winner's side at the end of each bout.

The gyōji's decision as to the winner of the bout can be called into question by one of the five judges who sit around the ring. If they dispute the result they hold a mono-ii (lit: a talk about things) in the centre of the ring, aided through an earpiece to a further two judges in a video room. They can confirm the decision of the gyōji, overturn it, or order a rematch. The gyōji is not expected to take part in the discussion during a mono-ii unless asked to do so. In many cases, a match may be too close to call, or the gyōji may not have managed to get a clear view of the end of the bout. Regardless, he is still obliged to make a split second decision as to his choice of "winner". This creates pressure for a gyōji, especially considering that a reversed decision is like a black mark: too many and it may affect his future career (such referees are never demoted; simply passed over for promotion).

In addition to refereeing matches, gyōji have a number of other responsibilities. During a tournament they select each tournaments day's matchups, and on tournament days selected gyōji announce each matchup as well as the kenshō sponsors. They also are responsible for keeping the records of wrestlers' results, and determining the technique used by a particular wrestler in winning a bout. Between tournaments, gyōji are involved in the ranking of wrestlers for the following tournament, which they then draw up an ornate ranking list written in painstaking calligraphy called a banzuke. All gyōji are also associated with one of the sumo training stables throughout their career and have many individual duties in assisting their stablemaster.

Ranking

Career progression is based on a ranking system similar in name to that used for sumo wrestlers (see sumo). The rank nominally represents the rank of wrestler that they are qualified to referee for. However, unlike sumo wrestlers, promotion is to a large degree determined on length of service. Typically a gyōji's promotion is only held up if he has made too many mistakes in determining the outcome of matches, except for the topmost rank where leadership skills may play a more significant role.

- tate-gyōji chief gyōji

- san'yaku-gyōji

- makuuchi-gyōji

- jūryō-gyōji

- makushita-gyōji

- sandanme-gyōji

- jonidan-gyōji

- jonokuchi-gyōji

Top gyōji (makushita ranked and above) are assigned tsukebito, or personal attendants in their stable, just as top wrestlers (sekitori) are. These may be junior referees or lower-ranked wrestlers. There is a superstition in the sumo world that a wrestler serving a gyōji will not go on to have a successful career.[1]

Uniform

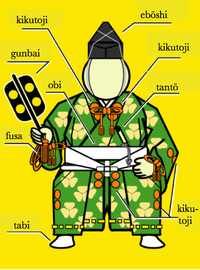

When refereeing matches senior gyōji wear elaborate silk outfits, based on medieval Japanese clothing from the Ashikaga period.

Like the sumo wrestlers, gyōji ranked at makushita level and below wear a much simpler outfit than those ranked above them. It is made of cotton rather than silk and is about knee length. The outfit also incorporates a number of rosettes (kikutoji), and tassels (fusa) which are normally green, but can be black in colour. Within the dohyō they are also expected to go barefoot.

On promotion to lowest senior rank of jūryō the gyōji will change into the more elaborate full length silk outfit. The kikutoji and fusa on his outfit will also change to be green and white. He is also entitled to wear tabi on his feet.

As he moves further up the ranks there are additional small changes:

Makuuchi ranked gyōji merely need to change the colour of the kikutoji and fusa to orange and white.

On achievement of san'yaku rank the rosettes and tassels become solid orange and he also is allowed to wear straw zōri on his feet in addition to the tabi.

As described above, the two holders of the topmost rank, equivalent to yokozuna and ōzeki, are the tate-gyōji. The kikutoji and fusa are purple and white for the lower-ranked tate-gyōji and solid purple for the higher-ranked one. Furthermore both the top two gyōji carry a tantō (a dagger) visible in the belt of the outfit. This is supposed to represent the seriousness of the decisions they must make in determining the outcome of a bout, and their preparedness to commit seppuku if they make a mistake. In reality if one of the two top-ranked gyōji has his decision as to the victor of a bout overturned by the judges then he is expected to tender his resignation instead. However, the resignation is generally rejected by the Chairman of the Japan Sumo Association. A tate-gyōji's submission of his resignation can usually be regarded as simply a gesture of apology from one of the highest-ranked referees for his mistake. There have, however, been rare cases where the resignation has been accepted, or where the gyōji concerned has been suspended from duty for a short period.

Ring Names

As with virtually all positions in the Sumo Association, including the wrestlers and the oyakata, the gyōji take on a professional name, which can change as they are promoted. Originally, and until the end of the Edo period these professional names were taken from a number of influential noble families associated with sumo, such as Kimura, Shikimori, Yoshida, Iwai, Kise and Nagase. Gyōji associated with these families derived their professional names from them. Over time however, noble families' influence on sumo waned until eventually only two "family" professional names remained, Kimura and Shikimori, with the titles having lost their connection with the families to which they were originally tied.

In modern times, all gyōji will take either the family name Kimura or Shikimori as their professional name, depending on the tradition of the stable that they join. There are exceptions to this naming convention, but they are rare. The professional name Kimura outnumbers the name Shikimori by about 3 to 1. Gyōji will at first use their own given name as their personal/second name which follows Kimura or Shikimori. Later, as they rise through the ranks and begin officiating higher divisions, one of the two family names and a personal name together as a set title is passed down. This will either be passed down from a senior gyōji (often a mentor) or the junior gyōji will receive one of a number of established gyōji professional names that is currently unused. This naming convention can be seen when looking at a list of gyōji such as on a banzuke, where younger, lower-ranked gyōji have modern sounding personal/second names, while higher ranked ones have antiquated sounding second names that have been passed down for generations. Rising through the ranks is based largely on seniority, but the accuracy of an individual gyōji's decisions and his bearing on the dohyō are also determining factors.

At the top of the gyōji hierarchy are two fixed positions called tate-gyōji which always take the names Kimura Shōnosuke and Shikimori Inosuke, the higher ranked and lower ranked tate-gyōji respectively. They officiate over only the top few bouts in san'yaku, near the end of a tournament day. Both of these professional names have the longest history and have been passed down through the most generations of gyōji. It is normally the practice that when the higher ranking Kimura Shōnosuke retires at 65, he is succeeded by the second ranking Shikimori Inosuke after a certain interval.

Latest tate-gyōji

- 37th Kimura Shōnosuke, real name: Saburō Hatakeyama, member of Tomozuna stable, November 2013 to March 2015.

- 40th Shikimori Inosuke, real name: Itsuo Nouchi, member of Miyagino stable, March 2013 to present.

See also

References

- ↑ Schilling, Mark (1994). Sumo: A Fan's Guide. Japan Times. p. 46. ISBN 4-7890-0725-1.

External links

![]() Media related to Gyōji at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Gyōji at Wikimedia Commons