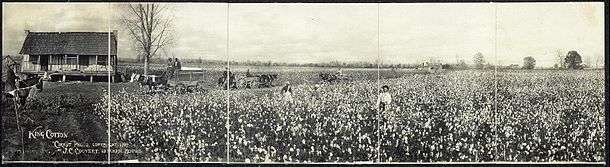

King Cotton

"King Cotton" as a slogan summarized the strategy used before the American Civil War of 1861–1865 by pro-secessionists in the Southern States (the future Confederacy) to claim the feasibility of secession and to prove there was no need to fear a war with the Northern States. The theory held that control over cotton exports would make a proposed independent Confederacy economically prosperous, would ruin the textile industry of New England, and—most importantly—would force Great Britain and perhaps France to support the Confederacy militarily because their industrial economies depended on Southern cotton. The slogan, widely believed throughout the South, helped in mobilizing support for secession: by February 1861, the seven states whose economies were based on cotton plantations had all seceded and formed the Confederacy (C.S.A.). Meanwhile, the other eight slave states, with little or no cotton production, remained in the Union.

To demonstrate the alleged power of King Cotton, Southern cotton-merchants spontaneously refused to ship out their cotton in early 1861; it was not a government decision. By summer 1861, the Union Navy blockaded every major Confederate port and shut down over 95% of exports. Since the British mills had large stockpiles of cotton, they suffered no immediate injury from the boycott; indeed the value of their stockpiles soared. For Britain to have intervened would have meant war with the U.S. and a cut-off of food supplies. About one fourth of Britain's food supplies came from the United States, and American warships could destroy much of British commerce, while the Royal Navy was convoying ships full of cotton. The British never believed in "King Cotton", and they never intervened. Consequently, the strategy proved a failure for the Confederacy—King Cotton did not help the new nation, but the blockade prevented earning desperately-needed gold. Most important, the false belief led to unrealistic assumptions that the war would be won through European intervention if only the Confederacy held out long enough.[1]

History

The American South is known for its long, hot summers, and rich soils in river valleys making it an ideal location for growing cotton. By 1860, Southern plantations supplied 75% of the world's cotton, with shipments from Houston, New Orleans, Charleston, Mobile, Savannah, and a few other ports.[2]

The insatiable European demand for cotton was a result of the Industrial Revolution which created the machinery and factories to process raw cotton into clothing that was better and cheaper than hand-made product. European and New England purchases soared from 720,000 bales in 1830, to 2.85 million bales in 1850, to nearly 5 million in 1860. Cotton production renewed the "need" for slavery after the tobacco market declined in the late 18th century. The more cotton grown, the more slaves were needed to pick the crop. By 1860, on the eve of the American Civil War, cotton accounted for almost 60% of American exports, representing a total value of nearly $200 million a year.

Cotton's central place in the national economy and its international importance led Senator James Henry Hammond of South Carolina to make a famous boast in 1858:

Without firing a gun, without drawing a sword, should they make war on us, we could bring the whole world to our feet... What would happen if no cotton was furnished for three years?... England would topple headlong and carry the whole civilized world with her save the South. No, you dare not to make war on cotton. No power on the earth dares to make war upon it. Cotton is king.[3]

Confederate leaders made little effort to ascertain the views of European industrialists or diplomats until the Confederacy sent diplomats James Mason and John Slidell in November 1861. That led to a diplomatic blowup in the Trent Affair.[4]

British position

When war broke out, the Confederate people, acting spontaneously without government direction, held their cotton at home, watching prices soar and economic crisis hit Britain and New England, causing a backlash with British public opinion. Even if Britain did intervene, it would mean war with the United States, as well as loss of the American market, loss of American grain supplies, risk to Canada, and much of the British merchant marine, all in the slim promise of getting more cotton.[5] Besides that, in the spring of 1861, warehouses in Europe were bulging with surplus cotton—which soared in price. So the cotton interests made their profits without a war.[6] The Union imposed a blockade, closing all Confederate ports to normal traffic; consequently, the South was unable to move 95% of its cotton. Yet, some cotton was slipped out by blockade runner, or through Mexico. Cotton diplomacy, advocated by the Confederate diplomats James M. Mason and John Slidell, completely failed because the Confederacy could not deliver its cotton, and the British economy was robust enough to absorb a depression in textiles from 1862–64.

As Union armies moved into cotton regions of the South in 1862, the U.S. acquired all the cotton available, and sent it to Northern textile mills or sold it to Europe. Cotton production increased in India by 70% and also increased in Egypt.

Economics

When war broke out, the Confederates refused to allow the export of cotton to Europe. The idea was that this cotton diplomacy would force Europe to intervene. However, European states did not intervene, and following Abraham Lincoln's decision to impose a Union blockade, the South was unable to market its millions of bales of cotton. The production of cotton increased in other parts of the world, such as India and Egypt, to meet the demand, and new profits in cotton was among the motives of the Russian conquest of Central Asia. A British-owned newspaper, The Standard of Buenos Aires, in cooperation with the Manchester Cotton Supply Association succeeded in encouraging Argentinian farmers to drastically increase production of cotton in that country and export it to the United Kingdom.[7]

Surdam (1998) asks, "Did the world demand for American-grown raw cotton fall during the 1860s, even though total demand for cotton increased?" Previous researchers have asserted that the South faced stagnating or falling demand for its cotton. Surdam's more complete model of the world market for cotton, combined with additional data, shows that the reduction in the supply of American-grown cotton induced by the Civil War distorts previous estimates of the state of demand for cotton. In the absence of the drastic disruption in the supply of American-grown cotton, the world demand for such cotton would have remained strong.

Lebergott (1983) shows the South blundered during the war because it clung too long to faith in King Cotton. Because the South's long-range goal was a world monopoly of cotton, it devoted valuable land and slave labor to growing cotton instead of urgently needed foodstuffs.

In the end, "King Cotton" proved to be a delusion that misled the Confederacy into a hopeless war that it ended up losing.[8][9]

See also

References

- ↑ Frank Lawrence Owsley, King Cotton Diplomacy: Foreign relations of the Confederate States of America (1931)

- ↑ Yafa 2004.

- ↑ TeachingAmericanHistory.org "Cotton is King" http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=1722

- ↑ Ephraim Douglass Adams, Great Britain and the American Civil War (1924) online ch 7

- ↑ Eli Ginzberg, "The Economics of British Neutrality during the American Civil War," Agricultural History, Vol. 10, No. 4 (Oct., 1936), pp. 147–156 in JSTOR

- ↑ Charles M. Hubbard, The Burden of Confederate Diplomacy (1998)

- ↑ Argentina Department of Agriculture (1904), Cotton Cultivation, Buenos Aires: Anderson and Company, General Printers, p. 4, OCLC 17644836

- ↑ Donald, David (1996). Why the North won the Civil War. p. 97.

- ↑ Ashworth, John (2008). Slavery, capitalism, and politics in the antebellum Republic. 2. p. 656.

Bibliography

- Blumenthal, Henry. "Confederate Diplomacy: Popular Notions and International Realities." Journal of Southern History 1966 32(2): 151-171. ISSN 0022-4642 in Jstor

- Hubbard, Charles M. The Burden of Confederate Diplomacy (1998)

- Jones, Howard, Union in Peril: The Crisis over British Intervention in the Civil War (1992) online edition

- Lebergott, Stanley. "Why the South Lost: Commercial Purpose in the Confederacy, 1861-1865." Journal of American History 1983 70(1): 58-74. ISSN 0021-8723 in Jstor

- Lebergott, Stanley. "Through the Blockade: The Profitability and Extent of Cotton Smuggling, 1861-1865," The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 41, No. 4 (1981), pp. 867–888 in JSTOR

- Owsley, Frank Lawrence. King Cotton Diplomacy: Foreign relations of the Confederate States of America (1931, revised 1959) Continues to be the standard source; online review

- Frank Lawrence Owsley, "The Confederacy and King Cotton: A Study in Economic Coercion," North Carolina Historical Review 6#4 (1929), pp. 371-397 in JSTOR; summary

- Scherer, James a.b. Cotton as a world power: a study in the economic interpretation of history (1916) online edition

- Surdam, David G. "King Cotton: Monarch or Pretender? The State of the Market for Raw Cotton on the Eve of the American Civil War." Economic History Review 1998 51(1): 113-132. in JSTOR

- Yafa, Stephen H. Big Cotton: How A Humble Fiber Created Fortunes, Wrecked Civilizations, and Put America on the Map (2004)