Kristiania Elektriske Sporvei

| Private aksjeselskap | |

| Industry | Tramway |

| Fate | Merger |

| Successor |

Oslo Sporveier Bærumsbanen |

| Founded | 1892 |

| Defunct | 1924 |

| Headquarters | Oslo, Norway |

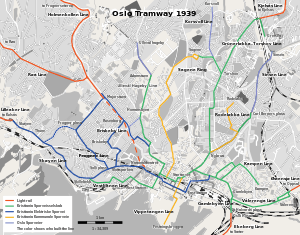

A/S Kristiania Elektriske Sporvei or KES, nicknamed the Blue Tramway (Norwegian: Blåtrikken), was a company which operated part of the Oslo Tramway between 1894 and 1924. It built a network of four lines in Western Oslo, the Briskeby Line and the Frogner Line which ran to Majorstuen, and two other consecutive lines, the Skøyen Line and the Lilleaker Line. These all connected to a common line through the city center which terminated at Jernbanetorget.

KES was established as the second tram operator in Oslo (then known as Kristiania). When it commenced services it was the first electric tramway in Scandinavia. It originally opened the Briskeby Line and the Skøyen Line to Skillebekk using a fleet of Class A trams. Later the company also ordered Class U and Class SS trams, for a total 78 motor cars and 66 trailers. Skøyen was reached in 1903. The first part of the Frogner Line opened in 1902, and it was completed in 1914. The Lilleaker Line was built to Lilleaker in 1919. KES and its competitor, Kristiania Sporveisselskab (KSS) were both taken over by Oslo Municipality in May 1924 and became Oslo Sporveier. The take-over did not include the Lilleaker Line and this part of the operation continued as Bærumsbanen.

History

Establishment

The Oslo Tramway was established as a horsecar network in 1875 by Kristiania Sporveisselskab. In 1887 it rejected a proposal for L. Samson, a real estate developer, to build a line to Majorstuen to serve his projects. He therefore contacted engineers H. E. Heyerdal and A. Fenger-Krog, the latter who had studied tramways abroad.[1] They sent an application that year to the municipality, at a time when there were no other electric tramways in operation in Europe. However, the application did not explicitly state that the company would use electric traction.[2] KSS retained it priority in laying new lines.[2]

The group received permission for two lines, one from Jernbanetorget, the square outside Oslo East Station, to Majorstuen. It would receive a branch from Inkognitogaten and Drammensveien to Skøyen,[3] a total distance of 6 kilometers (3.7 mi).[4] User of overhead wires had been discouraged by the city engineer, but he later changed his mind after a trip to Germany. The issue was decided upon by the municipal council on 19 May 1892.[3] The concession had a duration of thirty years, of which the municipality retained the right to municipalize the company after fifteen years and at the end of the duration.[4]

Shares worth 800,000 Norwegian krone (NOK) issued in October 1892, which sold out in a month. A/S Kristiania Elektriske Sporvei was incorporated on 16 December 1892. Heyerdal was appointed chair of the board, a position he held until his death in 1917. Fenger-Krog was hired as managing director. Six companies bid to deliver trams and electrical equipment; Allgemeine Elektrizitäts Gesellschaft (AEG) won and delivered seven Class A motor trams and five trailers. In June 1893 the contract to lay the tracks was issued to H. W. Wessel. The company applied the municipality to buy power from its Oslo Lysverker, but was rejected. It therefore decided to build a power station at Majorstuen. On the same lot it built the first depot, a prefabricated corrugated galvanized iron structure from Germany.[5] Investments totaled NOK 817,572.[6]

Early operations and expansion

Test runs started on 10 January 1894.[5] The official opening of the first Nordic electric tramway took place on 2 March 1894 and ordinary operation commenced the following day. It was the seventh electric tramway to open in Europe. Amongst the concerns in the public debate was that horses, such as those from the competing KSS, would not be able to cope with seeing a tram running without being pulled by a horse. The competitor's labor union proposed that KES used stuffed horses in front of their trams, but the horses soon learned to cope with the autonomous vehicle.[7] At first the trams ran every six minutes, but this proved difficult to operate and it was reduced to an eight-minute headway.[8]

Initially the motormen were to both drive and sell tickets, but this was found to be too much work for one person to do efficiently. Conductors were therefore introduced almost immediately.[9] It turned out that operating a correspondence between the Skøyen Line and the Briskeby Line at Parkveien did not work, as trams from Majorstuen were full and most passengers forced to walk into town. Thus from April KES introduced direct services from Skillebekk on the Skøyen Line to Jernbanetorget.[6] It quickly turned out the company had too few trams and four more were delivered by the end of the year. The Skøyen Line was extended to Frognergaden on 31 December.[10]

The original network was entirely single track with passing loops. The direct trams led to increased traffic and in 1896 KES therefore applied for permission to lay double track from Parkveien to Jernbanetorget.[11] As part of the permit, the municipality bought newly issued shares for NOK 200,000 to become shareholder of a fifth of the company.[12] Work commenced in 1898, which also included moving the tracks from Parkveien to Inkognitogaten and from Bogstadveien to Valkyriegaten.[11] The double track opened in 1898 to Majorstuen, and three years later on the Skøyen Line. The latter was combined with an extension to Thune.[8]

The company gradually expanded its fleet and by 1898 it had taken delivery of twenty-one Class A trams and twelve trailers. A year later a further six trailers were delivered.[13] Jørgen Barth took over as managing director in 1898.[14] The same year the Holmenkollen Line opened and at Majorstuen there was a transfer between the trams of KES and Holmenkolbanen.[15] The company took delivery of its first nine larger Class U trams in 1899. This was followed by a further five in 1902 and another five in 1905 and 1906.[16] From 1901 KES introduced regular stops instead of stopping on signal.[17]

The company's next task was extending the Skøyen Line and building a route via Frogner plass to Majorstuen. KSS had originally been given a permit to extend its Vestbanen Line to Frogener, but they were required to start construction within 1901. When they failed to do this, the municipality instead offered the permit to KES. The company started construction and the first part of the Frogner Line, from Parkveien to Frogner plass, opened in October 1902. That years KES was paying eight percent dividend.[18] The Skøyen Line, which was at the time named the Bygdøy Line, was extended to Skøyen on 21 June 1903.[19] There was little investment the following years, although in 1907 and 1908 the company built double track to Frogner and to Thune.[20] By 1907 the company had an annual revenue of NOK 700,000.[21]

Later operations

Leading up to the 1909 right of the municipality to buy the tramway, KES was evaluated at NOK 3 million in 1908. The issue was debated in light of the 1899 establishment of the municipal-owned Kristiania Kommunale Sporveie and the 1905 sale of it to KSS. There was no similar high-profile debate about munisipalization in 1908 as there had been in 1905. This was in part because there was by then a strong Conservative majority in the city council—a party who were opposed to municipal a tramway. Instead the municipality negotiated an agreement, whereby it secured itself four percent of the company's gross revenue, increasing to five percent from 1914.[21]

The power station was upgraded in 1909, cutting the coal usage from 4.0 to 1.3 kilograms (8.8 to 2.9 lb) per kilowatt hour. The company decided, mostly of concern for its employee's wellbeing, to cover up the tram's open platform bays.[20] This was in part sorted out through the purchase of new rolling stock. The final five Class U trains were delivered in 1909, bringing the total to twent-four.[22] Trams were at the time limited by the belief that they could not have a wheelbase exceeding a tenth of the minimum curve radius. This was proven wrong, allowing the tramway to order new and larger trams.[23] The first eight Class SS trams were delivered the same year. Deliveries resumed in 1912 and in the following two years a further twenty-six Class SS units were delivered.[24]

Numbered services were introduced in 1909. KES was the first of the two tramways to introduce numbered lines and secured the lowest digits. The Briskeby Line was numbered 1, the Frogner Line 2 and the Skøyen Line 3.[19] The increased rolling stock allowed most services to run every five minutes from 1910.[25] KES and KSS reached an agreement in 1912 to coordinate their services better. This first materialized in a connecting line in Hegdehaugsveien, which allowed trams to run from Stortorvet via the Ullevål Hageby Line to Majorstuen. At Skillebekk a connection was built through Munkedamsveien, allowing the Vestbanen Line access to the Skøyen Line.[26] In conjunction with the 1914 Jubilee Exhibition at Frogner, the Frogner Line was extended along Kirkeveien to Majorstuen on 15 May 1914.[19] In September a new depot opened at Majorstuen, with place for 75 vehicles—the largest in Scandinavia.[27]

The third connection opened in 1915, linking Jernbanetorget to the Kampen Line and the Vålerenga Line through a connection along Vognmannsgata, Brugata and Vaterland Bridge.[26] By 1915 the street tram network consisted of thirteen services, of which two were operated by KES and six were joint operations. All services via Homansbyen and Frogner to Majorstuen were joint services. The joint services were operated the relative number of trams in proportion of the ownership of trackage along the line and where each company simply kept the revenue it created on their services.[28] The first women conductors were hired in 1916.[29] Ten older Class A trams were rebuilt with larger wheelbase and bodies in 1918 and 1919, supplemented by 37 new motor trams and 56 new trailers.[30]

From the company's opening it had charged 10 øre for a ride,[30] but this was raised to 15 øre in 1918, a price which would remain unaltered for the rest of its history.[31] To ease management of such an odd amount, token coins were popular. They were sold with a quantity discount and were commonly used in Oslo as a conventional coin worth 15 øre.[32] During this period the country was experiencing inflation. KES and the labor union could not reach an agreement for wage increases and the company was hit by a strike from 11 January to 22 March 1920. It was resolved through the municipality offering to reduce its charges.[33] As part of the agreement, the 5 øre commuter prices in the morning and afternoon were abolished.[32]

The company started looking into a further extension of the Skøyen Line in 1912, intending to reach Bestum and Øraker. They applied for a permit in 1913, which was issued in July 1915. KES immediately started construction of the Lilleaker Line. Trial runs were carried out on 8 May 1919 and the line officially opened to Lilleaker the following day.[34] Unlike the rest of the network, the Lilleaker Line was built as a suburban light rail, running on an exclusive line rather than in the streets. KES started planning further extensions in 1917 and received permission in 1921 to extend the line to Avløs.[35]

Municipalization

KES and KSS both had concessions which expired on the same date, in March 1924. At this point the municipality was free to purchase the companies at par value. A municipal committee was appointed in 1922 to look into the matter. KES was valuated at NOK 9 million, while KSS was worth NOK 12.5 million. Oslo Municipality was not interested in taking over the Lilleaker Line, as it was situated in the neighboring municipality of Aker. The committees majority proposed a merger and that KSS received a prolonged concession, while the minority recommended that the tramways be bought by the city. A third option, a jointly public and privately owned company, was also proposed, where the municipality would own fifty-one percent.[36]

The issue was considered by the council's executive board, which supported the joint public–private proposal with eleven against nine votes. The argumentation was largely ideological: the left side accused the right for bringing economical advantages for private investors, while the right accused the left of insufficient financial investigations of municipal operations.[36] The issue was voted on in the municipal council in December, with 43 against 41 councillors supporting the joint model. The latter were members of the Communist Party and the Labor Party, who both were in favor of a municipal take-over. The new company, Kristiania Sporveier, was incorporated in May 1924 and took over all street tram operations. The city changed its name to Oslo on 1 January 1925, as did the tram company.[37]

With the municipalization, most of the assets were transferred to Oslo Sporveier. The exception was the Lilleaker Line, which was kept by the private company. That part was changed into a new tram company, Bærumsbanen. The street trams were transferred to Oslo Sporveier, although a few were kept until 1 July, when the Lilleaker Line was extended to Bekkestua. One the same day it took into use twelve Class A suburban trams.[38]

Network

KES operated a network consisting of a common line through the city center, three branches, a suburban line and three connections to KSS's network. The street tram network consisted of the Briskeby Line, the Skøyen Line and the Frogner Line. The Skøyen Line continued as the suburban Lilleaker Line. All of KES's lines remain in use.[19] The company's common section of track originated at Jernbanetorget, the square outside Oslo East Station. The line started in Strandgata and continued along Tollbugata to Akersgata. From there it cut across Stortingsgata and continued along Drammensveien.[10]

The Briskeby Line branches from the common section to Parkveien, where it took off onto Riddervolds gate and continued along Briskebyveien, Holtegata and Bogstadveien before reaching Majorstuen. The Skøyen Line runs along Drammensveien to Skøyen.[10] From Skøyen the Lilleaker Line continued to Jar.[39] The Lilleaker Line is a suburban light rail and runs in its own right-of-way along St. Edmunds vei, Bestumveien and Jonas Dahls vei.[35] The Frogner Line branched from the Skøyen Line at the intersection of Drammensveien and Frognerveiien at Solli plass, just after the Skøyen Line and the Briskeby Line split. The Frogner Line runs along Frognerveien to Frogner plass, the original terminus.[40] Since 1914 the line has continued along Kirkeveien to Majorstuen.[19]

The company operated one depot—Majorstuen Depot.[41] It consisted of three buildings, the largest of which had room for 75 vehicles.[27] It also featured the coal-fired thermal power station used to generate the electricity for the tramway.[20] Majorstuen was the site of the company's administration, as well as the depot for Holmenkolbanen. Most of KES facilities have been demolished, but one hall remains and is used by the Oslo Tramway Museum.[41]

Rolling stock

The company bought a total 78 motor cars and 66 trailers; 20 of the motorized vehicles were later converted to trailers. The deliveries were from various manufacturers, most of which were German. The sole Norwegian body manufacturer was Skabo. The trams were of three generations, each with their own class designation.[24] Many of the trams were of the same class as those delivered to KSS.[42] KES's trams were painted blue, hence giving rise to their nickname, the "Blue Tramway".[43]

The first class of trams, Class A, were manufactured by Allgemeine Elektrizitäts Gesellschaft (AEG) and P. Herbrand & Cie., both of Germany. The undercarriages were built by Bergische Stahlindustri. They featured open platform bays and a cabin. Twenty units were built, with nearly the same specifications. The trams were 6.5 meters (21 ft) long and 2.0 meters (6 ft 7 in) wide. They weighed 6 tonnes (5.9 long tons; 6.6 short tons) and were equipped with two NB80 motors with a combined effect of 12 kilowatts (16 hp). The exception was three units, no. 118 through 120, which had more powerful VBN120 motors, with a combined 36 kilowatts (48 hp). They had seating for sixteen and standing room for twelve. The company also had thirty-two similar trailer units built by Herbrand. One of the trams, no. 117, was a prototype built by Skabo with motors from Norsk Elektrisk & Brown Boveri.[44]

.jpg)

Twenty-four Class U trams were delivered between 1899 and 1906. The electrical components were built by Union-Elektricitäts-Gesellschaft and the bodies by Falkenried and Skabo. The trams had two GE52 motors with a combined power output of 36 kilowatts (48 hp) and had a total weight of 10.2 tonnes (10.0 long tons; 11.2 short tons). They were 7.8 meters (26 ft) long and were built with open platform bays. Each unit had capacity for twenty seated and fourteen standing passengers.[45] Two units were in 1924 rebuilt to create an articulated tram. However, it proved prone to derailment in poorly banked S-curves and was never put into revenue service.[46]

KES took delivery of thirty-four Class SS motorized trams and twenty-two trailers between 1909 and 1914. They had electrical components from Siemens-Schukertwerke and were variously built by Herbrand, Falkenried and Skabo. Their main innovation was that the wheelbase was increased from 180 to 360 centimeters (71 to 142 in), allowing for a lengthening of the body. The first eleven were 9.69 meters (31.8 ft) long, while the rest were 11.47 meters (37.6 ft) long. The first eight units had two D72v motors, giving a combined power output of 72 kilowatts (97 hp). Later units had a power output of 84 kilowatts (113 hp).[47]

The second delivered unit, no. 102, has been preserved by the Norwegian Museum of Science and Technology.[48] Two SS motor units, no. 307 from 1913 and no. 322 from 1918, and one trailer, no. 347, have been preserved by the Oslo Tramway Museum.[49]

References

- ↑ Fasting: 41

- 1 2 Fasting: 42

- 1 2 Fasting: 43

- 1 2 Fasting: 44

- 1 2 Fasting: 45

- 1 2 Fasting: 48

- ↑ Fasting: 48

- 1 2 Fristad: 27

- ↑ Fristad: 26

- 1 2 3 Fristad: 25

- 1 2 Fasting: 51

- ↑ Fasting: 52

- ↑ Fristad: 29

- ↑ Fasting: 55

- ↑ Fristad: 32

- ↑ Fristad: 29

- ↑ Fasting: 63

- ↑ Fasting: 59

- 1 2 3 4 5 Aspenberg: 7

- 1 2 3 Fasting: 70

- 1 2 Fasting: 69

- ↑ Aspenberg: 43

- ↑ Fasting: 71

- 1 2 Aspenberg: 43

- ↑ Fasting: 72

- 1 2 Fristad: 52

- 1 2 Fristad: 82

- ↑ Fristad: 54

- ↑ Fasting: 83

- 1 2 Fristad: 62

- ↑ Fristad: 64

- 1 2 Fristad: 65

- ↑ Fasting: 89

- ↑ Bærumsbanen: 3

- 1 2 Gaarder, Håkon Kinck (2001). "Bærumsbanen". Lokaltrafikk (in Norwegian). 44: 4–19.

- 1 2 Fasting: 91

- ↑ Fasting: 92

- ↑ Strandholt: 10

- ↑ Strandholt: 10

- ↑ Fristad: 28

- 1 2 Aspenberg: 37

- ↑ Aspenberg: 45

- ↑ Fasting: 50

- ↑ Andersen, Bjørn (1997). "De første «electrikkene»". Lokaltrafikk (in Norwegian). 34: 4–12.

- ↑ Andersen, Bjørn (1995). "Unionvognenes historie". Lokaltrafikk (in Norwegian). 25: 10–22.

- ↑ Budmiger, Roy (1995). "«To rom og kjøkken»". Lokaltrafikk (in Norwegian). 29: 17–19.

- ↑ Andersen, Bjørn (1994). "SS-vognene". Lokaltrafikk (in Norwegian). 21/22: 4–29.

- ↑ Aspenberg: 44

- ↑ "Sporveismuseets vognsamling" (in Norwegian). Oslo Tramway Museum. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

Bibliography

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kristiania Elektriske Sporvei. |

- Aspenberg, Nils Carl (1994). Trikker og forstadsbaner i Oslo (in Norwegian). Oslo: Baneforlaget. ISBN 82-91448-03-5.

- Bærumsbanen (1944). Bærumsbanen 1919–1944 (in Norwegian).

- Fasting, Kåre (1975). Sporveier i Oslo gjennom 100 år: 1875–1975 (in Norwegian). Oslo: Grøhdal & Søn. ISBN 82-504-0116-6.

- Fristad, Hans Andreas (1990). Oslo-trikken – storbysjel på skinner (in Norwegian). Oslo: Gyldendal. ISBN 82-05-19084-4.

- Hartmann, Eivind; Mangset, Øistein (2001). Neste stopp!: Verneplan for bygninger (in Norwegian). Oslo: Baneforlaget. ISBN 82-91448-17-5.

- Strandholt, Thorleif (1990). A/S Kristiania elektriske sporvei : Lilleakerbanen åpnet 9. mai 1919 overtatt 1924 av A/S Bærumsbanen ; A/S Akersbanene stiftet 7. juni 1917 ; Østensjøbanen, åpnet 18. desember 1923 som opphørte/overtatt 1949 av A/S Bærumsbanen, stiftet 1. mai 1924 som ble overtatt 1971 av A/S Oslo Sporveier (in Norwegian). Copenhagen: Sporvejshistorisk Selskab. ISBN 8787589311.