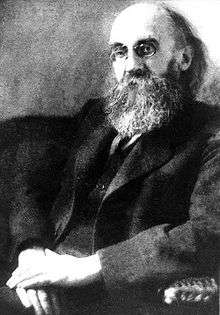

Kurt Eisner

| Kurt Eisner | |

|---|---|

| |

| Minister President of Bavaria | |

|

In office 1918–1919 | |

| Preceded by | Otto Ritter von Dandl |

| Succeeded by | Johannes Hoffmann |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

14 May 1867 Berlin, Kingdom of Prussia |

| Died |

21 February 1919 (aged 51) Munich, Free State of Bavaria |

| Nationality | German |

| Political party | Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany |

| Religion | Judaism |

Kurt Eisner [kʊʁt ˈaɪ̯snɐ] (14 May 1867 – 21 February 1919)[1] was a German-Jewish journalist, theatre critic, and pacifist. As a socialist journalist and statesman, he organised the Socialist Revolution that overthrew the Wittelsbach monarchy in Bavaria in November 1918.[1] He is used as an example of charismatic authority by Max Weber.[2] He proclaimed the Free State of Bavaria. His followers, who included Rosa Luxemburg, were known as "Eisenachers".

Biography

Kurt Eisner was born in Berlin at 10:15 p.m. on 14 May 1867, to Emanuel Eisner and Hedwig Levenstein, both Jewish. He was married to painter Elisabeth Hendrich from 1892, with whom he had five children, but the couple eventually divorced in 1917 and Eisner then married Elise Belli, an editor. With her, he had two daughters.

Eisner studied philosophy, but then became a journalist in Marburg. From 1890 to 1895, he was contributing editor of the Frankfurter Zeitung, during which time he wrote an article attacking Kaiser Wilhelm II, and for which he spent nine months in prison.[3] Eisner was always an open republican as well as a Social-Democrat, joining the SPD in 1898, although for tactical reasons, German Social-Democracy, particularly in its later stages, rather cold-shouldered anything in the shape of republican propaganda as being unnecessary and included in general Social-Democratic aims. Consequently, he fought actively for political democracy as well as Social-Democracy. He became editor of Vorwärts after the death of Wilhelm Liebknecht in 1900, but was subsequently called upon to resign from the position in 1905. After that, his activities were confined in the main to Bavaria, though he toured other parts of Germany.[4][5] He was chief editor for the Fränkische Tagespost in Nuremberg from 1907 to 1910, and afterwards became a freelance journalist in Munich.

Eisner joined the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany in 1917, at the height of World War I, and was convicted of treason in 1918 for his role in inciting a strike of munitions workers. He spent nine months in Cell 70 of Stadelheim Prison, but was released during the General Amnesty in October of that year.[6]

After his release from prison, Eisner organized the revolution that overthrew the monarchy in Bavaria (see German Revolution). He declared Bavaria to be a free state and republic on 8 November 1918, becoming the first republican premier of Bavaria. On 23 November 1918, he leaked documents, from the Bavarian plenipotentiary in Berlin during July and August 1914, which he thought proved that the war was caused by "a small horde of mad Prussian military" men as well as "allied" industrialists, capitalists, politicians, and princes.[7] At the Berne Conference of Socialists, held at Berne, Switzerland, he attacked moderate German socialists over their refusal to acknowledge Germany's part in bringing about World War I. For that speech, and for his uncompromising hostility to Prussia, he became bitterly hated by large sections of the German people.[3]

As the new government was unable to provide basic services, Eisner's Independent Social Democrats were soundly defeated in the January 1919 election.

Death and legacy

Eisner was assassinated in Munich when German nationalist Anton Graf von Arco auf Valley shot Eisner in the back on 21 February 1919. Eisner was on his way to present his resignation to the Bavarian parliament. His assassination resulted in the elected government fleeing Munich and the establishment of the brief Bavarian Council Republic and parliament.

When the Passau labor union tried to stage a play about Eisner at the bishopric theater in 1920, Reichswehr soldiers and high school students sabotaged it, using weapons from the military arsenal. Among other things, eleven machine-guns were used. The incident, dubbed the Passau Theater Scandal, triggered media headlines and a variety of judicial procedures.[8]

In 1989, a monument was installed in the pavement at the site of Eisner's assassination. It reads, "Kurt Eisner, der am 9. November 1918 die Bayerische Republik ausrief, nachmaliger Ministerpräsident des Volksstaates Bayern, wurde an dieser Stelle am 21. Februar 1919 ermordet." ("Kurt Eisner, who proclaimed the Bavarian republic on 8 November 1918 – later Prime Minister of the Republic of Bavaria – was murdered here on 21 February 1919.")

Works

Eisner was the author of various books and pamphlets, which include:[5]

- Psychopathia Spiritualis (1892, "Spiritual Psychopathy")

- Eine Junkerrevolte (1899, "A Junker revolt")

- Wilhelm Liebknecht (1900)

- Feste der Festlosen (1903, "Celebration of Fixed Lots")

- Die Neue Zeit (1919, "The New Age")

References

- 1 2 "Kurt Eisner - Encyclopædia Britannica" (biography), Encyclopædia Britannica, 2006, Britannica.com webpage: Britannica-KurtEisner.

- ↑ Max Weber, (London 1987) p.634

- 1 2

Reynolds, Francis J., ed. (1921). "Eisner, Kurt". Collier's New Encyclopedia. New York: P.F. Collier & Son Company.

Reynolds, Francis J., ed. (1921). "Eisner, Kurt". Collier's New Encyclopedia. New York: P.F. Collier & Son Company. - ↑ Obituary, Unsigned, Justice, 27 February 1919, p.6; transcribed by Ted Crawford. Please see: http://www.marxists.org/history/international/social-democracy/justice/1919/19_02_27.htm

- 1 2

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1922). "Eisner, Kurt". Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.). London & New York.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1922). "Eisner, Kurt". Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.). London & New York. - ↑ Richard J. Evans The Coming of the Third Reich, 2003.

- ↑ Holgar, Herwig (1987) "Clio Deceived: Patriotic self-censorship in Germany after the Great War". International Security 12(2), 9.

- ↑ Anna Rosmus Hitlers Nibelungen, Samples Grafenau 2015, pp. 27f

Further reading

- Universitätsbibliothek Regensburg - Bosls bayrische Biographie - Kurt Eisner (in German), author: Karl Bosl, publisher: Pustet, page 172

- Biography Kurt Eisner (in German)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kurt Eisner. |

- Picture of Kurt Eisner, taken in early 1918 Historisches Lexikon Bayerns

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Otto Ritter von Dandl |

Prime Minister of Bavaria 1918–1919 |

Succeeded by Johannes Hoffmann |